The Wellbeing Toolkit Training Programme: A Useful Resource for Educational Psychology Services?

Abstract

Background. Supporting pupils’ social, emotional, and mental health (SEMH) development is a task that schools are expected to undertake in England, yet many staff members find it challenging due to their belief that they don’t possess the necessary skills.

Objective. To evaluate a commercially available, training resource, The Emotional Wellbeing Toolkit, aimed at raising the skills of adults working with children in the SEMH area.

Design. The Toolkit was adapted and used as training material by a professional team comprised of educational psychologists, clinical psychologists, and specialist teachers, for schools within an eastern region in England. A mixed methodology was employed to evaluate the usefulness of the Toolkit as a training resource, as well as its perceived effectiveness in raising the skills of school professionals working within the SEMH area. Qualitative as well as quantitative data was gathered from the two groups participating in training, as school staff delegates, and as facilitators of training delivery. Descriptive statistics and content analysis were used for data analysis.

Results. The findings suggest evidence of improved skills and knowledge in the area of SEMH, with some specific impact on delegates’ practice. Implications for practice are discussed.

Received: 24.09.2019

Accepted: 25.11.2019

Themes: Educational psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2019_4/Psychology_4_2019_210-225_Bunn.pdf

Pages: 210-225

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2019.0413

Keywords: Wellbeing Toolkit, school, training, emotional wellbeing, mental health, psychology

Introduction and Context

Social, emotional, and behavioural difficulties of children are a continuing and rising concern in the UK. In the local authority in which the study took place, mental health problems are estimated to affect 9.4% of children and young people, equating to 10,160 people aged 5–16 (Gummerson, 2015). This is not a far stretch from national statistics, whereby 9.6% of children aged 5–16 had a mental health condition a decade ago (Children’s Commissioner for England, 2018), and 2.6% of the age 5–17 population received targeted interventions via Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services in 2017. Some believe that such figures represent only a minority of the 20–25% of children with an impairing mental health condition who are estimated to have contact with mental health services (Children’s Commissioner for England, 2018), whether inside the school or with external services (Ford, Vostanis, Meltzer, & Goodman, 2007).

With health resources continuing to be squeezed, educational settings are increasingly expected to support the SEMH of pupils. Schools’ consistent contact with their pupils implies that they could influence the pupils’ mental health (DfE & DoH, 2017) and SEMH is increasingly seen as relevant to schools, as it has an unequivocal impact on learning (Hagell, Coleman, & Brooks, 2013).

The Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) Code of Practice: 0 to 25 years (DfE & DoH, 2015) introduced mental health, alongside earlier social emotional terminology, to the schools’ agenda. More recently, “Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: A Green Paper” (DfE & DoH, 2017) continued this trend, underlining that schools play a key role in SEMH early intervention and prevention work.

With current and emerging legislation that emphasizes the role of schools in promoting mental health and emotional wellbeing, it falls to schools to adopt strategies and approaches to support SEMH as well as to initiate pathways into mental health care. Yet while a number of non-statutory guidelines have been published for schools since, there is less evidence about which specific training programmes in the SEMH area are effective for school staff.

Literature Review

A literature search in the area of mental health training in schools was undertaken in 2017 as part of the current study. The search brought up relevant literature within three areas, explored below: training children for their own mental health, training staff to support child mental health, and training staff for their own wellbeing.

1. Training Children for Their Own Mental Health

The recent years appear to have brought a focus on student-led interventions whereby children are taught the skills to manage and support their own emotional wellbeing. Boniwell, Osinc, and Martinez (2015) looked into the effectiveness of 18 bi-weekly lessons in the promotion of happiness and wellbeing skills, delivered by teachers to eight groups of 20–30 students. They concluded that the sessions had a buffering effect for students, protecting them against known risk factors (such as decline in satisfaction with self or with friends) as well as increasing their positive affect. Another study which investigated the impact of a positive psychology course on student wellbeing, depressive symptoms, and stress, stated that this may be an effective way to improve students’ mental health (Goodmon, 2016). Interventions such as mindfulness courses are known to be effective in improving mental health, wellbeing, and academic attainment (Bennett & Dorjee, 2016).

2. Training Staff for Child Mental Health

In the task of embedding mental health support in schools, studies have shown the importance of children and young people having teacher support for both academic and social-emotional outcomes. Interestingly, the limited literature available in this area suggests that interventions led and implemented by school staff are as effective as those involving external professionals (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnickj, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011) and enable a more sustainable delivery. Jorm et al. (2010) found that after a mental health first aid training course, high school teachers showed increased knowledge and reduced stigma and changed some aspects of their behaviour with respect to mental health. Students also reported receiving more mental health information from their teachers.

Other types of programme have trained teachers in running a wellbeing curriculum to teach skills in mental health and wellbeing to their students. A meta-analysis of 213 school-based, universal social and emotional learning (SEL) programmes involving 270,034 kindergarten through high school students demonstrated that SEL participants had significantly improved social and emotional skills, attitudes, behaviour, and academic performance, when compared to those not receiving the intervention (Durlak et al., 2011). Other surveys on teachers’ experiences of applying what they have learned in a training course have suggested increased empathy and confidence, and feeling better able to handle crises (e.g., Jorm, Kitchener, Sawyer, Scales, & Cvetkovski, 2005). A study by Viera et al. (2014) seems to indicate that child development and general mental health topics in teacher training curricula should be part of a teacher’s continuing education.

3. Training Staff for Staff Mental Health

Recent years have seen an emphasis on staff wellbeing as having an impact on outcomes for children and young people. A survey of 160 schools in Birmingham showed, for instance, that high levels of work-related stress in teachers can have a serious impact on their mental health and affect their ability to provide effective early intervention to support their students’ emotional wellbeing, causing them to withdraw from student support or leave teaching altogether (Palmer, Connor, Newton, Patterson, & Birchwood, 2015). Teachers seem to feel that their emotional needs are often neglected (e.g., Kidger, Gunnell, Biddle, Campbell, & Donovan, 2010) and this might suggest that schools should endorse whole school approaches to mental health, and encourage awareness in staff and students. A recent programme for educators, the Community Approach to Learning Mindfully (CALM) (Harris, Jennings, Katz, Abenavoli, Greenberg, 2016) has shown significant benefits for educators’ social-emotional competence and wellbeing, prevention of stress-related problems, and support for classroom management.

Overall, the literature seems to suggest that schools can, with appropriate training, be involved in early identification and work with children and young people in the area of SEMH. There appear to be some school-based programmes to enhance the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people, through working with the children and the school staff, which have beneficial effects. In this climate, the Wellbeing Toolkit was produced, with the promise of adding to this body of resources. A local authority educational psychology service agreed to incorporate the Toolkit as part of their training offer and to evaluate its effectiveness by a variety of means. Description of the journey from design to delivery and evaluation of the Toolkit constitutes the body of this paper, which will hopefully add to the existing knowledge about SEMH programmes and will inform the reader in making a decision among mental health programmes available on the market.

The Wellbeing Toolkit

The key aims of the Toolkit are to allow professionals and staff who work with children and young people to:

-

“Learn relevant therapeutic approaches and skills;

-

“Feel confident that they have developed the appropriate skills and knowledge base to identify at-risk students;

-

“Help prevent the escalation of any perceived difficulties and problems; and

-

“Fulfil Inclusion (Section 4) of the National Curriculum (2014) – by enhancing the emotional wellbeing of students and providing particular support for those experiencing social, emotional and/or behavioural difficulties, lessons can be planned to ensure that there are no barriers to every pupil achieving” (“The Wellbeing Toolkit”, n.d.).

Method

The Educational Psychology Service, which delivered the Toolkit, is a multi-disciplinary service consisting of a number of professionals, including educational psychologists, specialist teachers, and clinical psychologists. As SEMH is on the forefront of its service delivery, it contacted the Toolkit’s publishers and, in agreement with them, proceeded to deliver the Toolkit to school staff, making any amendments that its trainers considered necessary. A total of 110 participants were exposed to one or more of the Toolkit sessions. Participants included staff from 36 schools. Exact demographics of the schools were not obtained; however, 46 participants attended from primary, 11 from infant, 20 from junior, 27 from secondary, and 6 from specialist, schools. The majority of the participants attended four sessions, whereas 11 participants attended nine or more sessions.

A multi-method approach for data gathering was used and included information related to:

-

Recording of changes each facilitator made to the initial Toolkit sessions;

-

Written records produced by each facilitator; they focused on their reflections on:

- a. Delegates’ confidence about implementing information and strategies from the sessions;

- b. Delegates’ overall response to information and activities;

- c. Usefulness of information; and

- d. Usefulness of skills learned.

-

Delegates’ evaluations following each training session included:

Quantitative information on:- a. Overall satisfaction;

- b. Most useful aspects of session;

- c. Aspects that could be improved upon;

- d. Overall presentation;

- e. Information transmitted;

- f. Skills practiced;

- g. Materials provided;

- h. Degree that expectations were met through the session;

Qualitative accounts focused on:

- a. Most useful aspects of session;

- b. Aspects that could be improved upon;

- c. Comments on how the session met expectations;

- d. What delegates need more of to assist understanding.

-

Delegates’ views four months after the final session, captured via online survey and related to:

- a. Overall rating of the Toolkit;

- b. Skills acquired;

- c. Skills, strategies, or resources implemented in school following the programme;

- d. Skills that were not gained from the programme, but would have been useful to gain;

- e. Further support needed to implement learning in school;

- f. Three main strengths of the programme;

- g. Whether they would recommend the programme to other schools.

The evaluation methods were produced by the Educational Psychology Service working group. Schedules used for data gathering are available in the Appendix.

A total of 306 evaluation sheets were completed over the 19 sessions. Thirty-nine participants consented to take part in the follow-up survey, although only 10 completed it. Data collected was evaluated using descriptive statistics and content analysis (Krippendorff, 2013).

Results

The findings are presented within the four areas relevant for the Toolkit delivery and presentation: (1) session changes the facilitators made; (2) delegates’ immediate evaluation of the sessions; (3) delegates’ follow-up survey; and (4) facilitators’ reflections.

1. Session Changes the Facilitators Made

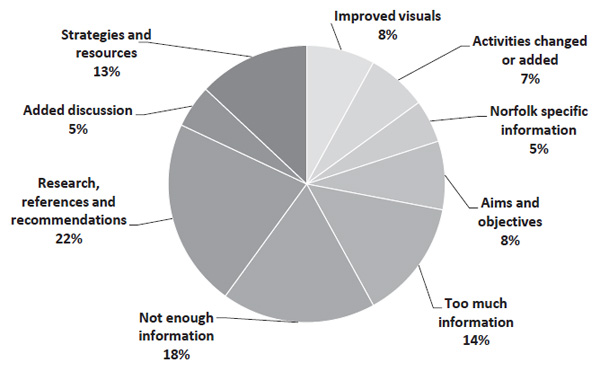

Out of the 19 sessions delivered, five sessions (26%) incurred no changes to the presentations; slides were added to presentations for eight sessions (42%) and were removed from presentations for six sessions (32%). Figure 1 is a visual representation of the types and frequency of slide changes.

Figure 1. Percentage of the types of slide changes

2. Delegates’ Immediate Evaluations

Delegates were asked to comment on whether each session met their expectations and their overall satisfaction with the session. With regards to all the sessions delivered, 95.75% of delegates found the materials offered either very useful or useful; 98.95% found the presentation of information to be very useful or useful; and 73.5% considered the skills they practiced during the sessions either very useful or useful. Finally, 97.7% found the information transmitted during the sessions very useful or useful. Overall, 78.1% of delegates felt that the sessions met their expectations and 19.6% felt that the sessions partially met expectations.

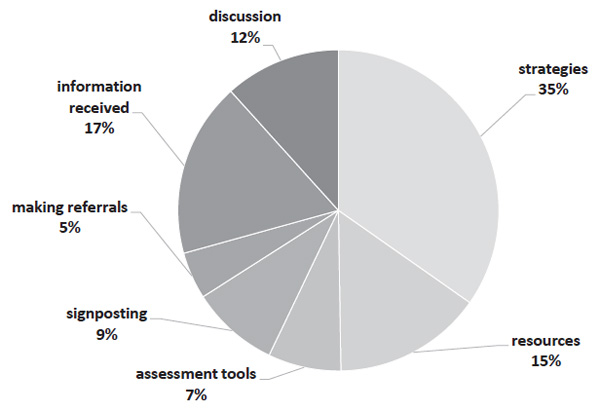

Delegates were asked to rate their overall satisfaction with the sessions, with the result that 38.9% said they were very satisfied with the sessions; 58.2% felt they were satisfied, and 1.6% were dissatisfied. Figure 2 is a visual representation of the prominence of themes relating to aspects of the session delegates found useful.

3. Qualitative Analysis

a) Most useful aspects of the session

Further content analysis of the qualitative data suggested that themes such as strategies, information received, and resources

shared in the sessions were most useful for delegates, alongside some less prominent themes such as discussion, signposting to other services, assessment tools, and making referrals. Strategies related to “how to involve families”, “developing a school policy”, “practical activities to use in class”, and “a reminder of good practice” were the most useful to apply in schools. Information received was also a prominent theme across all 19 sessions. Here statistics, government guidelines, theory behind practice, and background information relating to the tools, strategies, and models discussed were most useful for the delegates to apply in schools and enhance their learning. Resources distributed within the sessions was also a prominent theme across most sessions, with delegates valuing resources in the form of “handouts”, “online support/info”, and “new info, books, services available”. Delegates also valued the discussions in the sessions, as they felt that these allowed “sharing with other professionals”, “sharing best practices”, and “great self-reflection and thoughts on how this can impact our children”. Advice about how and when to make referrals, signposting

to other services, and receiving information relating to the use of assessment tools in schools were also clear themes in the feedback for particular sessions.

Figure 2. Prominence of themes relating to aspects of the session that delegates found useful

b) Aspects that could be improved upon

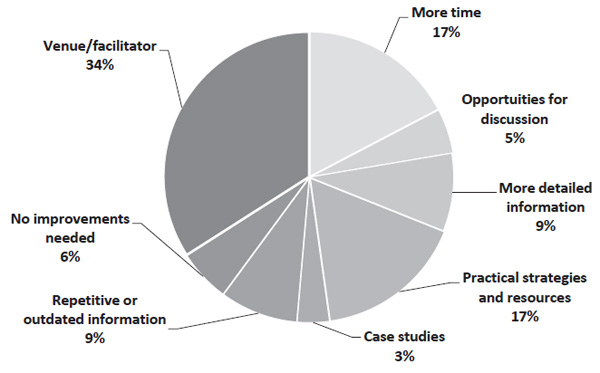

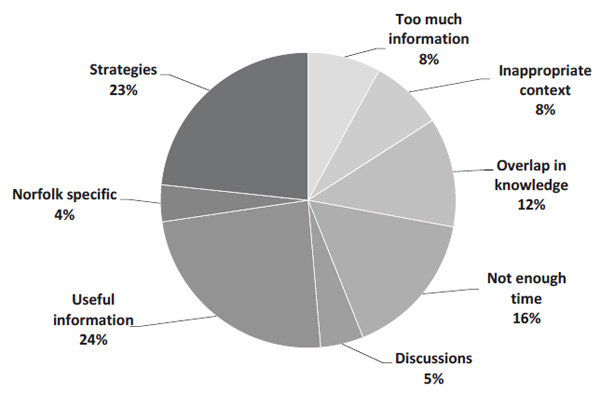

Delegates evaluated how the sessions could be improved upon. The following themes were most prominent: the venue or facilitator, more time, and more practical strategies and resources. Figure 3 offers a visual representation of the themes identified. Issues relating to the practicalities of the session, such as the venue or facilitator, accounted for 34% of the feedback received; however, these reflections relate to environmental and technical hazards (e.g. too cold in the room, technology not functional). Delegates felt that more time was required for each session, as there was “so much information to take in in a short period of time” and “so much interesting stuff – need more time”. More practical strategies and resources was an equally prevalent theme. Delegates suggested that it “would have been useful to have a few more direct links and practical applications in school” and would be beneficial to have “more time spent on practical tools”. Less dominant themes included repetitive or outdated information and more detailed information. A few delegates found in one instance that there was “out-of-date data – 10 years old”, which was “repetitive on quite a few slides”. Comments relating to more detailed information correspond with comments relating to the lack of time available in each session and hopes for “greater explanation/focus on general application”. Many fewer participants reflected that case studies (6%) and opportunities for discussion (5%) would have enhanced the sessions; 3% of delegates felt that no improvements were needed.

Figure 3. Prominence of themes relating to aspects of the session that could be improved upon

c) How the sessions met expectations

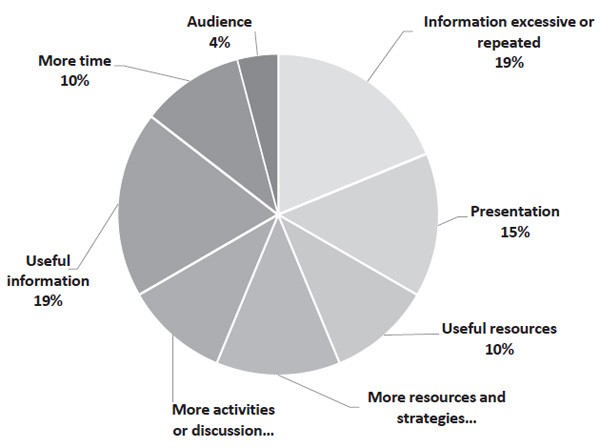

The participants’ responses on how the sessions met expectations generated a number of themes, visually represented in Figure 4. They found useful information throughout the sessions, as 19% of comments related to “very interesting information” and “very positive session with info that can be easily distributed and made use of”. However, in equal measure (19%), some delegates felt that information was repeated or not pitched at the right level with regards to the delegate’s previous knowledge or level of training: “no new information or assessments learned from this session” and “very similar to previous training I have attended”. The presentation, in terms of style and delivery, was positively commented upon by 15% of responses, with comments including “presenter’s knowledge and sharing of it and proactive approach to solving problems” and “great presentation, clear and concise with very helpful content”. Thirteen percent of participants said that they would expect more resources and strategies from the sessions, with suggestions such as “probably more practical ideas and examples” and “I was hoping for websites to assist my learning”. Other themes included useful resources (10%), more activities or discussion (10%), and more time (10%), common throughout the evaluations. Finally, 4% of comments related to the audience, in terms of information being more suited to a specific age group, or regarding the practicalities of getting staff to implement their learning.

Figure 4. Prominence of themes relating to how sessions met delegates’ expectations

d) What more to assist understanding?

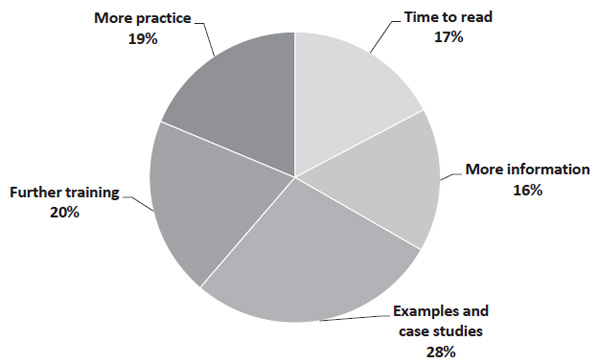

An emerging theme was that more examples and case studies would assist the trainees’ understanding. They felt that “more time spent on specific examples/case studies so we could see them in action”, “more practical solutions”, and “more strategies that could be used in the classroom” would assist their understanding of the session. Further training was a second prominent theme (represented by 20% of responses) in the form of “possible INSET (nb: INSErviceTraining) day” or “more courses targeted towards TA’s” and “follow-up sessions will be of great help”. Delegates also identified needing more practice to assist their understanding of what they had learned during the sessions, as this would give them experience, and “simply to practice some more of the skills and activities”. Time for further reading to “digest all of the full size information (in my own time)” and “read suggested materials” was another theme identified in 17% of the responses. More information on particular topics, get “more in-depth knowledge”, or “further research” was the last theme identified.

Figure 5. Themes showing what delegates need more of to assist understanding

e) Any other comments

This contained generally positive comments, with delegates offering their thanks and praise relating to the usefulness of the Toolkit sessions. Comments included, “Good session, lots of areas covered, just needed more time”, “Will be good for other schools”, and “Plenty of pointers to good websites”. Other comments reflected the criticisms highlighted in other questions, such as “lots of listening – will need to spend lots of time looking these up (skills) – time is precious”, “having some scenarios of problems”, and “useful information, allowing for time constraints may have been useful to do some more practical tasks (but I understand why!)”.

4. Delegates’ Follow-Up Survey

Although there was a reduced response rate (25.6%) to the online follow-up survey, some information can still be usefully drawn. Participants belonged to primary (70%), secondary (10%), and specialist schools (20%).

A largely positive appreciation of the Toolkit was expressed, with 20% rating it as “very good” and 60% as “good”. The high positive appreciation straight after the sessions was moderated four months later. Eighty percent of delegates said they would recommend that the programme be delivered to schools locally and nationally.

The answers to “What skills did you acquire following the sessions you attended?” largely related to “ideas to use with groups of children and staff”, “knowledge about assessment and resources available”, and “great links to further reading and research”. The participants appreciated the practical information and resources from the sessions and these responses correlate with themes identified from their responses to “aspects of the sessions you found useful” in the previous section. This is further supported by responses to the survey question: “Did you implement any skills strategies or resources in your school following the programme?” Participants implemented a wide range of skills, strategies, and resources that they had gained from the programme, including art therapy skills, strategies around supporting children with SEMH difficulties, facts and figures on mental health in children, and “adapting our supervision system, and will take into account the training we had as part of this plan going forward”.

The participants indicated in retrospect what skills they felt would have been useful to gain from the Toolkit. Their answers were largely similar to the post-session evaluation forms, highlighting themes related to: deepening understanding through receiving more information, “some of the issues such as family breakdown … I would have liked to look at in further depth”; the opportunity to practice skills, or further training, e.g., “Lego training”. Similarly, the answers to “What further support would you need in order to implement your learning?” included engagement of other agencies, which links to delegates’ appreciation for support in understanding how to make referrals and also where to refer children. One participant considers the need for “periodic workshops to keep updated”, which mirrors post-session feedback related to further training. Other delegates offered more practical suggestions: “to have online access to the kit” and “it would be nice to have more time for planning sessions with children…”. Others expressed the feeling that no further support is required.

The main strengths of the Toolkit described were that it was “well planned”, had “up-to-date facts and figures”, “enthusiastic and knowledgeable trainers”, “very good presenters”, “short sessions”, “supporting materials”, and was “accessible to those with basic understanding”.

5. Facilitators’ Reflections

The last aspect of the Toolkit’s evaluation is the facilitators’ written reflections, produced shortly after the session. This data was gathered in terms of confidence and knowledge and practical strategies/suggestions. The median for all features measured was 4 (on a 5-point Likert scale, where 5 is best). The features included delegates’ overall satisfaction, usefulness of information, and usefulness of skills learned. This seems to complement what the delegates expressed.

Confidence and Knowledge of Delegates

Facilitators’ responses related to the confidence and knowledge that participants gained from the sessions are visually represented in Figure 6. One of the most prominent themes was the usefulness of the information given to delegates (24%). Facilitators felt that the information improved delegates’ confidence by increasing their knowledge, added to their understanding, and gave them evidence on which to base their practice. Twenty-three percent of facilitators’ reflections related to strategies. Facilitators referred to strategies in the general sense, in terms of whole school approaches, such as “I think it helps set the tone of what we are encouraging staff to do, which is to become good observers, active listeners, … and to know when and where to refer [the student to another practitioner]”; others were more specific, for example, “We discussed strategies such as active listening and how to do it … and most staff understood this and seemed confident about its usage”. The facilitators also felt that there was not enough time (16%) to give the required level of information and skill development to allow for participants to feel confident in using some of the information. An overlap in delegates’ knowledge (12%) was identified by some, who felt that “some parts of the presentation had been seen in previous sessions of the programme” and “there was lots of material in the session which participants were familiar with”.

Figure 6. Confidence and knowledge gained by delegates, as perceived by facilitators

Practical Strategies/Suggestions

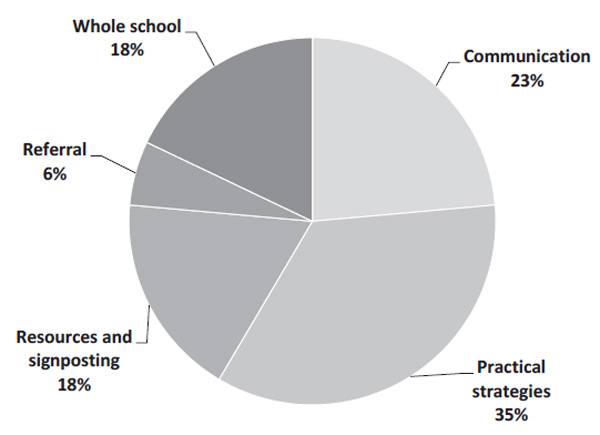

The facilitators were asked to reflect on the practical strategies provided during their session. Their reflections were split into two areas, related to either the type of strategies delivered or their reflections about the delivery and delegates’ understanding of the strategies (see Figures 7 and 8).

The strategies given to delegates were related to either practical strategies (35%), communication (23%), resources and signposting (18%), whole school strategies (18%), or referrals (6%). Practical strategies relates to intervention, assessment, or activities that can be used in schools. Communication was another prominent theme and an important strategy for schools to adopt to develop relationships and enhance skills in working with not only children, but also with other adults. Strategies relating to resources and signposting were commonly referred to: “I also mentioned contacting their Duty Officer at CAMHS [Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services] for enquiries…”. Whole school strategies were also well represented: “There were some Heads [of schools] in the audience, so after explaining risk and resilience factors, I included an activity on how a school could develop protective factors”. Finally, strategies relating to referrals were discussed in one particular session: “One of the things I focused on was how to make a good referral to a Tier 2…”.

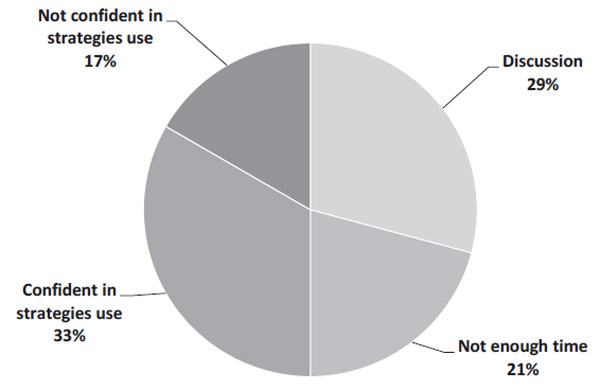

Figure 7. Types of strategies delivered, as perceived by facilitators

Additionally, 33% of the facilitators felt that the strategies they presented were useful to the delegates; however, 17% of them were less confident. One facilitator reflected, “I don’t think this session allowed time for useful practice or understanding of any of the practical strategies”; this is echoed in the delegates’ evaluations, where they said they needed more opportunities to practice their skills. Not enough time was a theme reflected upon by facilitators, with some commenting, “This session felt like it was trying to do too many things in too short a period”. Last but certainly not least, discussion was a prominent theme throughout facilitators’ reflections, as represented by comments such as “… there were good ideas generated from the discussion points made, indicating a good grasp of the importance of whole school development”. Discussions were well received by participants, evident in their post-session evaluation forms, and the facilitators clearly found this element of the session to be equally useful, not only to demonstrate understanding, but also to learn from colleagues and share experiences.

Figure 8. Reflections about delivery and delegates’ understanding of strategies

Conclusions

The Toolkit is a significant SEMH training delivery resource, targeted to raise the skills of adults working with children and young people. The current study seems to suggest that, although the delivery of the training requires some significant resources from any specific service, its effectiveness may compensate for the professional effort related to time required for session attendance and delivery.

Both the facilitators and delegates involved in this project identified some significant strengths in the Toolkit training, related to school staff becoming more confident and knowledgeable in the area of SEMH, both issues having been previously identified in other studies as areas of weakness in school staff. It appears that the school staff participating in this study became more knowledgeable about other provisions out there and how to refer specific cases to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, if necessary. Even four months after the training, at least a quarter of the delegates still benefited from the teaching provided within the Toolkit sessions. Apart from matters related to environment and presentation format, it looks like substantive improvements in the delivery of the SEMH training could be related to organising follow-up workshops and discussions, and access to the Toolkit.

Overall, the study is suggestive that the Toolkit has been effective in providing theoretical and practical skills to the school staff in their work in the SEMH area. The Toolkit is broadly universal in its application, making it attractive as a training tool for mainstream schools. As such, the authors believe that educators in mainstream schools could undertake training in the Toolkit, which is an efficient way of raising the skills of school staff in working with SEMH students. The findings have been disseminated to a couple of regional and national conferences in the UK, and there were a number of educators and educational psychologists who enquired further about the Toolkit, with the view of using it in education.

An identified limitation of the study is that a relatively high proportion of school staff who initially consented to participation did not complete the follow up survey. This may have biased the survey results, favouring those participants who had strong opinions about the Toolkit. Additionally, it is acknowledged that, although the training was delivered to a diverse school staff population, it had, nonetheless, captured only those who were interested in taking part in the training. This means, yet again, that school staff attending the training might have already been attracted to such a programme, hence more likely to implement the training.

This said, it is likely that the Toolkit training was indeed effective, and that its effectiveness can be attributed, at least partly, to the materials taught as well as those delivering the training. It is possible that the educational psychology practitioners have the unique skills of combining SEMH knowledge with educational setting knowledge to effectively train school practitioners in identifying and dealing with low-level SEMH difficulties in schools.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by Norfolk County Council, Educational Psychology and Specialist Support team. We thank our colleagues from Educational Psychology and Specialist Support who provided practical insight that greatly assisted the research, although they may not agree with all of the interpretations and conclusions of this paper.

We thank Mrs Adair, Senior Educational Psychologist, for her assistance with the practical coordination of the training.

We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewer(s) for their very valuable international insights which greatly improved the quality of this article.

References

Bennett, K. & Dorjee, D. (2016). The impact of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Course (MBSR) on well-being and academic attainment of sixth-form students. Mindfulness, 7(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0430-7

Boniwellab, I., Osinc, E.N., & Martinez, C. (2015). Teaching happiness at school: Non-randomised controlled mixed-methods feasibility study on the effectiveness of Personal Well-Being Lessons. The Journal of Positive Psychology: Dedicated to furthering research and promoting good practice, 11(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1025422

Children’s Commissioner for England (2018). Children’s mental health briefing. A briefing by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner for England. Retrieved from https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/childrens-mental-health-briefing...

DfE & DoH (Department for Education & Department of Health) (2017). Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: A Green Paper. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/transforming-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-provision-a-green-paper

DfE & DoH (Department for Education & Department of Health) (2015). Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years. Statutory guidance for organisations which work with and support children and young people who have special educational needs or disabilities. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/398815/SEND_Code_of_Practice_January_2015.pdf

Durlak, J.A., Weissberg, R.P., Dymnickj, A.B., Taylor, R.D., & Schellinger, K.B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Ford, T., Vostanis, P., Meltzer, H., & Goodman, R. (2007). Psychiatric disorder among British children looked after by local authorities: Comparison with children living in private households. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 190, 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025023

Goodmon, L.B., Middleditch, A.M, Childs, B., & Pietrasiuk, S.E. (2016). Positive psychology course and its relationship to well-being, depression, and stress. Teaching of Psychology, 43(3), 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628316649482

Gummerson, C (2015, July). Health profile of children and young people in Norfolk. Key health-related issues for people aged 0–19 years. Retrieved from: http://www.norfolkinsight.org.uk/resource/view?resourceId=1106Hagell A., Coleman, J., & Brooks, L. (2013). Key Data on Adolescence 2013. The latest information and statistics about young people today. Retrieved from http://www.ayph.org.uk/publications/457_AYPH_KeyData2013_WebVersion.pdf

Harris, A., Jennings, P., Katz. D., Abenavoli, R., & Greenberg, M. (2016). Promoting stress management and wellbeing in educators: Feasibility and efficacy of a school-based yoga and mindfulness intervention. Mindfulness, 7(1), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0451-2

Jorm, F., Kitchener, B., & Mugford, S. (2005). Experiences in applying skills learned in a mental health first aid training course: A qualitative study of participants' stories. BMC Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-5-43

Jorm, A., Kitchener, B., Sawyer, M., Scales, H., & Cvetkovski, S. (2010). Mental health first aid training for high school teachers: A cluster randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-51

Kidger, J., Gunnell, D., Biddle, L., Campbell, R., & Donovan, J. (2009). Part and parcel of teaching? Secondary school staff's views on supporting student emotional health and well-being. British Educational Research Journal, 36(6), 919–935. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920903249308

Krippendorff, K (2013). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 3rd Edition. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., McLuckie, A., & Bullock, L. (2013). Educator mental health literacy: A programme evaluation of the teacher training education on the mental health & high school curriculum guide. Advances in School Mental Health Provision, 6(2), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2013.784615

Office for National Statistics (2018). Counts and percentages of adults with a mental illness, by various breakdowns, May–July 2012 to 2017, UK. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/mentalhealth/datalist on 18.3.2018

Palmer, C., Connor, C., Newton, B., Patterson, P., & Birchwood, M. (2015). Early intervention and identification strategies for young people at risk of developing mental health issues: Working in partnership with schools in Birmingham, UK. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12264

Reinke, W. M., Herman, K. C., & Sprick, R. (2011). Motivational interviewing for effective classroom management: The classroom check-up. New York: Guilford Press.

The Wellbeing Toolkit (n.d.). Retrieved from https://nurturegroups.org/news/wellbeing-toolkit-0

Vieira, M.A., Gadelha A.A., Moriyama, T.S., Bressan, R.A., & Bordin, I.A. (2014). Evaluating the effectiveness of a training program that builds teachers’ capability to identify and appropriately refer middle and high school students with mental health problems in Brazil: An exploratory study. BMC Public Health, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-210

Vostanis, P., Humphrey, N., Fitzgerald, N., Deighton, J. & Wolpert, M. (2013). How do schools promote emotional wellbeing among their pupils? Findings from a national scoping survey of mental health provision in English schools. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18(3), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00677.x

To cite this article: Bunn, H., Turner, G., Macro, E. (2019). The Wellbeing Toolkit Training Programme: A Useful Resource for Educational Psychology Services? Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 12(4), 210-225.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.