Motivations of High School Students of Different Sex and Age

Abstract

Background. e actual motive may be experimentally diagnosed through study of the system of perceived motivations. However, since perceived motivations are always expressed in terms that are not unambiguous (for a number of reasons, including age, gender, context, etc.), the experimental reconstruction of the actual motive is always as- sociated with an ambiguity in interpretation of the respondents’ perceived motivations. We need to use a method of diagnosing motivations that would allow us to identify, for the groups of students studied, not only the contribution of a particular perceived moti- vation, but also the substantive features of the designated motives, through the pattern of correlations of these perceived motivations.

Objective. This article presents the results of research on the age and gender specifics of learning motivations of high school students.

Design. Experimental identication of their motivational proles was made by means of factor analysis, separately for each of four groups of pupils (in Moscow schools with a traditional learning paradigm): two junior groups (8th-9th grades, 14-15 years old) of boys (62) and girls (59); and two senior groups (10th-11th grades, 16-17 years old) of boys (63) and girls (54).

Results. As a result, a motivational structure specic for the corresponding gender and age was identied and described.

Conclusion. We showed that as a child grows up, the orientation in learning becomes more and more generalized, with a stronger expression for boys than for girls. In the junior group, girls have a motivation that is oriented to the future, whereas boys do not; such motivations in boys are seen only in the senior group and are inextricably linked to the parents’ approval. Both for boys and girls, the content of their motivation for cognitive achievement in the older age group is based on two motives, which are independent at the younger age: curiosity and prestige. However, with girls, apart from a desire to learn new things, the aspiration to differ notably from others and to demonstrate their achievements to others is significantly greater than with boys

Received: 24.10.2017

Accepted: 31.07.2018

Themes: Educational psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2018_3/psych_3_2018_15_Vartanova.pdf

Pages: 209-224

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2018.0315

Keywords: motivation, learning activity, older adolescents, gender, personal development

Introduction

In adolescence, significant transformations occur in mental and personal development (Bozhovich, 1995), and the motivational sphere undergoes qualitative changes. This period is characterized by the development and strengthening of motives appropriate to mature forms of learning activities. Broad cognitive motives are being strengthened, and the motives of self-improvement, self-education, achievement, and self-realization continue to develop. Social motives become noticeably enhanced. Fundamental qualitative changes occur in the narrow social, i.e., positional, motives of learning. The motivational structure becomes more stable. Adolescents' stable personal interests make them purposeful, create conditions for the will to become self-regulating (Bozhovich, 1995; Ivannikov et al., 2014). However, it is precisely at this age that we can observe a decline in academic progress and a reduction of learning motivation (Badmaeva, 2006; Dotterer et al., 2009; Lepper, Corpus & Iyengar, 2005; Otis & Pelletier, 2006; Grouzet et al., 2006).

A significant contribution to the motivation for learning is made by individual characteristics, which to a significant extent are determined by gender. From the earliest stages of development, there are specific aspects in the socialization of boys and girls, in their assimilation of cultural rules, which reflect their visions of the different social roles of males and females in a given society (Bern, 2004). The connection between gender identity and social anxiety in young people has been studied by Pavlova and Kholmogorova (2017), Garcia-Lopez, Ingles, and Garcia-Fernandez (2008), Peleg (2012), and Moscovitch, Hofmann, and Litz (2005). A number of studies have found differences in the psychological characteristics of students of different sexes (Kudinov, 1998; Sobkin & Kalashnikova, 2015; Babaeva, 2012; Arutiunova & Alexandrov, 2016).

The reasons for gender differences have been explained by stereotypes of masculinity and femininity in the public consciousness, as well as by the historically developed forms of interaction between males and females (Kletsina, 2013). Corresponding psychological differences appear also in the motivational sphere, in manifestations of curiosity that depend on gender (Kudinov, 1998). In the study of younger adolescents, it was found that the attitude of girls to their studies is governed by the desire for social success, while for boys, it is by extrinsic motivation (to occupy a certain position, the respect of their peers). Girls are more inclined to consider learning activities as an important factor in their future professional and social success, whereas among boys, the percentage of those who are not at all motivated to study is much higher (Sobkin & Kalashnikova, 2015). Analogous results have been obtained in analyses of older adolescents (Gordeeva, 2013; Lupart et al., 2004; Walls & Little, 2005): Boys express extrinsic motivation (acknowledgement by their schoolmates, approval by their parents, and respect from their teachers) more than girls, while girls are more oriented to the motivation for achievement.

There are also distinctive age features in the motivation to learning activities. V.S. Sobkin and E.A. Kalashnikova (2015) analyzed the age-specific motivations for learning activity, conditioned by changes in the conceptual position of younger adolescents (6th-9th grades). From the 6th to the 8th grades, the conceptual position of girls involves their attitude toward self-realization and social success, which reflects the personal significance of their learning activities. By the 9th grade, with tude. A shift occurs from a positive motivation toward learning activities to a negative attitude toward the pragmatic usefulness of the knowledge acquired at school. Absolutely different age-specific characteristics are manifested in boys. Already at the turn of the 6th to 7th grades, their conceptual position is characterized both by a negative attitude toward the knowledge received at school, as well as by extrinsic motivation for learning activities. The same conceptual position is also characteristic of boys in the 9th grade (Sobkin & Kalashnikova, 2015). In other studies (e.g., Gordeeva, 2013), cognitive motives were shown to increase at the turn of the 6th to 7th grades, but by the 9th to 11th grades they declined. Some authors (e.g., Gordeeva, 2013) note that the gender differences in motivation are manifested only in the senior grades: Starting with 9th grade, girls seem to have a more pronounced (intrinsic) motivation for achievement and a less pronounced extrinsic motivation, as compared with boys. Others (Sobkin & Kalashnikova, 2015) detect gender-related differences in learning motivation at an earlier age – starting with the 6th grade. Western researchers are also actively studying the influence of parents and teachers, and age-specific changes in learning motivation (Eccles & Roeser, 2003).

Thus the identification of genderand age-specific motivation at senior school age is an important question for understanding both the personality structure and the mechanisms of its development in the course of schooling.

Another important problem is that of experimental identification of the motivational structure of the personality. By "motive," we usually mean the internal reason that prompts and directs a person's activities, and which is inaccessible to direct observation. Furthermore, learning activity is usually polymotivated (Bozhovich, 1995; Leontiev, 1993), and each motive may have its own qualitative identity for numerous reasons – personal maturity and age, education, gender, etc. In introspection, the motives appear in the form of perceived motivations [1] – conscious interpretations and explanations of one's own behavior and that of others. The actual motive may be experimentally diagnosed through study of the system of perceived motivations. However, since perceived motivations are always expressed in terms that are not unambiguous (for a number of reasons, including age, gender, context, etc.), the experimental reconstruction of the actual motive is always associated with an ambiguity in interpretation of the respondents' perceived motivations. Thus one and the same perceived motivation may have different meanings for students of different genders and ages (Vizghina & Pantileev, 2001). Therefore, the diagnostics of motives for learning, with the purpose of identifying students' ageand genderspecific characteristics, appears to present a very important independent problem.

The motive as a qualitatively unique structure underlying the perceived motivations has to be diagnosed separately for students of different ages and genders. A simple approach, typical of the majority of studies of ageand gender-specific motivation of learning activity, which is based on direct comparison of the results of students' evaluations of what is formally one and the same motivation, seems to be insufficient. It may appear, for instance, that boys and girls assess a certain perceived motivation identically, and we may therefore assume that it expresses one and the same motive; but in reality, this motivation has absolutely different meanings for the boys and girls, and is part of a structure of absolutely different motives, determining their qualitative singularity.

The use of simple statistics for intergroup comparison is therefore incorrect in this case. We need to use a method of diagnosing motivations that would allow us to identify, for the groups of students studied, not only the contribution of a particular perceived motivation, but also the substantive features of the designated motives, through the pattern of correlations of these perceived motivations. Such meaningful features may be formalized as a factor model, whereby the factor is correlated with a certain motive, but its content is determined by the factor loads – the extent of contribution to it by a particular motivation, or by a corresponding profile of perceived motivations. An important parameter may also be the total number of factors that determine the general motivational profile, or the extent of polymotivation of a given learning activity.

The purpose of this work is to identify the ageand gender-specific motivations (motivational profiles) of high school students in the pursuit of their studies.

We may hypothesize that for pupils of different genders and ages, the systems of motivation for a learning activity will differ, both in the number of motives that establish the motivational profile, and in the structure of the motives themselves, determined by the perceived motivations of which they are composed.

Methods

We developed a special questionnaire to study perceived motivations for learning activity (Vartanova, 2015). It is comprised of 70 items reflecting possible variants of perceived learning motivations at school, both at the present time and with respect to a future career. The extent of the student's agreement with each statement was assessed on a 5-point scale. Factor analysis was used to identify the motives, using statistical estimation of the number of allocated factors and factor rotation to achieve a simple structure (by the normalized Varimax method). This made it possible to interpret the inner structure of the factors through the weights of the perceived motivations. Identification of gender and age specifics was achieved by comparing the factor structure obtained by separate analysis of the scores of each of the four groups of students.

Participation in the survey was voluntary (with the parents' consent); the subjects were students in the 8th-11th grades at two Moscow schools with a traditional teaching paradigm (N = 238), divided into four groups, each of which was analyzed separately: the junior groups (8th-9th grades, 14-15 years old) of boys (62) and girls (59), and the senior groups (10th-11th grades, 16-17 years old) of boys (63) and girls (54).

The survey was conducted in several schools in Moscow, equally representing different types of learning environment (an advanced curriculum school and a regular district education center), each of which uses various educational programmers' humanitarian, mathematical, biological and so on. In the upper grades of educational institutions in Moscow it is accepted that all subjects are taught by different teachers, therefore the teaching style of specific teachers in this regard could not systematically influence the formation of sense relation to the learning activity of students of this sampling. The study compared groups of schoolchildren of different sexes and ages allocated in each of the studied educational institutions, so the impact of unaccounted factors associated with a particular educational institution on the results of comparing them within the allocated groups was minimal.

Results

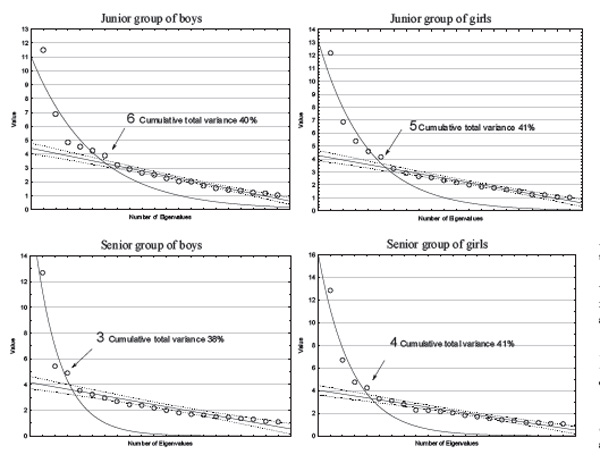

The scores were processed by factor analysis for each of the four groups separately (according to age and gender). The dimension of the factor spaces obtained was estimated according to Cattell's scree test, with the results shown in Figure 1. The plots show that the junior boys are distinguished by six attributes (factors) from the set of statements (items) on the questionnaire, and the boys of the senior group by only three. The girls of the junior group are distinguished by five such attributes (factors), and those of the senior group by only four. We may conclude from this that as children grow up, their orientation to the importance of learning becomes more and more generalized, and this is more pronounced in boys than in girls.

The factors identified in each group were interpreted as follows:

In the group of junior boys, Factor 1 may be denoted as "the need for recognition and a sense of obligation" (includes 17 with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5). It includes statements that show awareness of the need for successful study, including duty and responsibility, as well as the need for approval from parents and teachers (the urge to comply quickly and correctly with the teachers' demands). Factor 2 may be denoted as "cognition (curiosity)", which includes statements (5 with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5) on the role of cognition and novelty (to find an explanation for everything, to discover new ways of problem solving). Factor 3 may be denoted as "self-esteem (status motivation)", in which the items (7 with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5) chosen are dominated by the desire to occupy a rightful place among one's schoolmates, and the feeling that academic success enhances one's significance and merit. Factor 4 may be denoted as "superiority (+duty and responsibility)", since the items (8 with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5) that comprise it describe a desire to know more than others, to study well because only a knowledgeable person is needed by others, to be the best pupil in the class. Factor 5 may be denoted as "orientation to the group", which includes items (5 with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5) about acceptance and social approval from parents or the peer group. Factor 6 may be denoted as a "functional motive (taking pleasure in the learning process)". It contains items (6 with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5) indicative of a wish to attend only classes that are interesting to them. In addition, all factors of motivation in the group of junior boys include items connected with self-esteem, realized in different ways depending on the principal motive.

In the group of senior boys, the items are grouped into more generalized factors. Factor 1, which may be denoted as "cognitive achievement", includes items (13 with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5) that express the desire to learn as much as possible, to understand the academic material as well as possible, to overcome difficulties, to find new ways of solving problems, to prove oneself. Thus, the factor contains items that earlier (in the junior group) were included in the factor of cognition as a process (factor 2), as well as partially the prestige factor (factor 4). Factor 2 may be denoted as "orientation to the future" (includes 11 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5); the items that comprise it express pragmatic motives about the importance of knowledge for future success in work and life, whereby marks in school are important in order to live up to the expectations of one's parents and society, to be appreciated as cultural and educated persons. Recognition of the need for knowledge in order to have a successful future appears first with the senior boys. This partly includes items about duty and responsibility that enter into factor 1 for junior boys. Factor 3 may be denoted as "affiliation" (includes 10 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5), the need for respect and approval from parents, teachers and schoolmates, the desire to increase one's own authority (status).

Figure 1. Eigenvalues for each of the groups of students. On the left are the boys, on the right the girls. At the top are the junior groups (8th–9th grades), at the bottom the senior groups (10th–11th grades). Relevant eigenvalues are approximated by an exponential, and the values determined by random noise are approximated by a straight line (the dotted lines show 95% confidence intervals). Figures with an arrow mean the last relevant size

In the group of junior girls, factor 1 may be denoted as "orientation to the future" (includes 12 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5). As with the senior boys, the items that characterize it include pragmatic motives of the importance of knowledge for future success in work and life, the desire to live up to the expectations of parents and society, to be appreciated as cultured and educated persons. Factor 2 may be denoted as "cognitive motivation" (includes 10 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5). Like the junior boys, the junior girls want to know more and to find an explanation for everything; they like to conduct independent research, to invent new ways of solving problems. Unlike the boys, marks for them are not the important thing; it is more important to learn something new and interesting. Factor 3 may be denoted as pursuit of "superiority (prestige)" (includes 10 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5). Like the junior boys, the girls want to be the best pupils in the class, to occupy a rightful place among their schoolmates, for their answers in class to be better than all the others'. They value participation in academic competitions only as a way to assert themselves. Unlike the boys, for them it is very important to make everybody notice that they know much more than the other pupils. Factor 4 may be denoted as "orientation to the group" (includes 8 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5). Junior girls like classes that allow them to work in a group; they want to receive good marks, to study better, in order to win their friends' respect. Unlike boys of the same age with analogous motivations, they aspire only to approval from a reference group of peers, and not from parents and teachers. Factor 5 may be denoted as "self-esteem" (includes 7 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5). Unlike boys of their age with analogous motivations (who often study in order to win approval from adults and friends), the girls of junior age assert themselves through success in their studies. They like to study, they want it to last as long as possible. They like to express their point of view in class and to defend it. They have developed the habit of working successfully at school, achieving good results; they do not imagine themselves behaving any other way in the learning process. Similar results were obtained in a cohort of young adolescent girls in a study by Sobkin and Kalashnikova (2015).

In the group of senior girls, factor 1 may be denoted as "orientation to the future" (includes 15 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5). Like the boys of the same age, they are already thinking about what college to attend. They study to become cultured and educated, to acquire the knowledge necessary for further studies and a prestigious job. At the same time they are trying to live up to the teachers' expectations.

Unlike the junior girls and senior boys with analogous motivation, parental approval is not very important to them. Factor 2 may be denoted as "achievement" (includes 16 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5), which determines their orientation to the process and outcome of learning – to find out new things, discover different ways to solve problems, conduct independent research, participate in academic competitions – in order to assert themselves, to be better than the others. Unlike the boys, it is very important for them to make others notice that they know, and know how to do, much more than everyone else. This factor includes the items that in the junior group constituted part of the factor of cognition as a process (factor 2), as well as of the factor of pursuit of superiority (prestige) (factor 3). For the senior girls, factor 3, which may be denoted as "affiliation through social approval of peers" (includes 6 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5), describes the girls' aspiration to be well regarded by schoolmates, to live up to their teachers' expectations, to win their friends' respect. At the same time, they are afraid of discussing the schoolwork with schoolmates and defending their point of view. Factor 4 may be denoted as "affiliation through acceptance and approval by adults" (includes 5 items with absolute Factor Loadings > 0.5). Unlike the previous factor, this one includes items from which it follows that it is especially important to have the approval of parents and teachers; good studying for them means gratifying their parents. Thus, in the senior girl group, unlike the senior boys, the affiliative motives are divided into two independent but complementary parts.

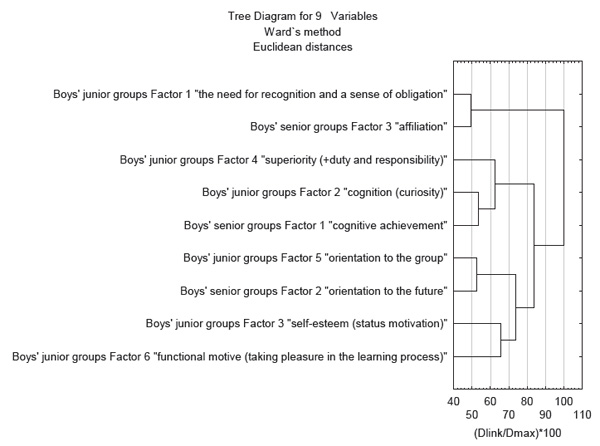

Figure 2. Age-specific changes in the boys' groups. Result of cluster analysis.

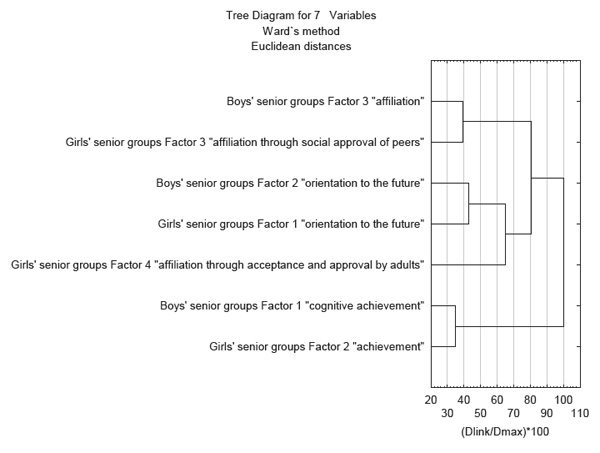

A formal comparison of the allocated factors (according to their factor loads) among the groups, with respect to gender and age, was conducted by cluster analysis (the magnitude of the difference was defined as the Euclidean distance; the Ward clustering method was used).

Age-specific changes in the boys' groups (Figure 2):

-

The motive of cognitive achievement (factor 1 of the senior group) puts together the items that, in the junior group, entered into factors 2 (cognition and curiosity) and 4 (superiority – to know things better than the others).

-

The motive of pragmatic orientation to the future (factor 2 of the senior group) includes mainly the items that, in the junior group, entered into factors 3 (self-esteem, status motivation) and 6 (functional motive, taking pleasure in the learning process), as well as some items from factor 1 (sense of obligation and need for recognition).

-

The affiliation motive (factor 3) of the senior group mainly includes the items from factor 1 of the junior group (need for recognition). The "urge to realize quickly and correctly the teachers' demands" is declining.

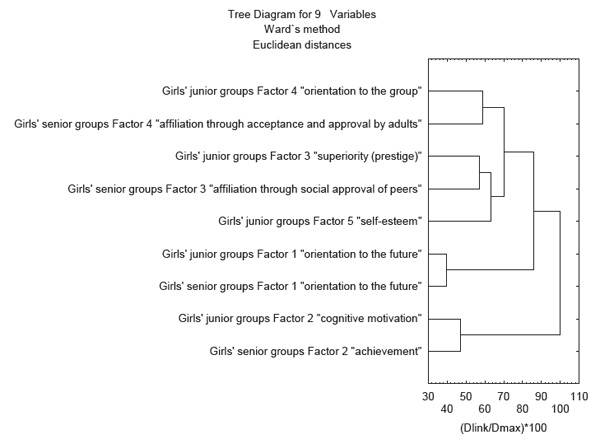

Figure 3. Age-specific changes in the girls' groups. Result of cluster analysis

Age-specific changes in the girls' groups (Figure 3):

-

The factor of pragmatic orientation to the future (factor 1) of the senior group has mainly preserved the items that make up part of the analogous factor 1 of the junior group, but it has become more structured and "adult" – it has lost the items connected with good marks and an expectation of parental approval (these have moved to factor 4, affiliation).

-

The motive of cognitive achievement (factor 2) in the senior group also preserves mainly the items of the analogous factor 2 of cognitive motivation of the junior group, but adding items connected with the fact that the older girls want to be better in their studies than others (in the junior group, this is included in factor 3, superiority). Furthermore, this factor includes several items of factor 5 — selfesteem through academic success, as a conscious need.

-

The motive of affiliation, social approval in the reference group (factor 3 of the senior group) partially includes the items of factor 5 (self-esteem) of the junior group.

-

The affiliation motivation (orientation towards the family, factor 4) of the senior group partially includes items of factor 1 (orientation to the future, connected with the parents' attitudes), but items are also reinforced that are connected with expectations of adults' approval (parents and teachers).

It should be noted that factors 3 and 4 of the senior group of girls are more similar to each other (in the content of their items and in connection with the need for acceptance), but they differ from each other in that, in the first case, the acceptance is expected from peers, and in the second case, from adults.

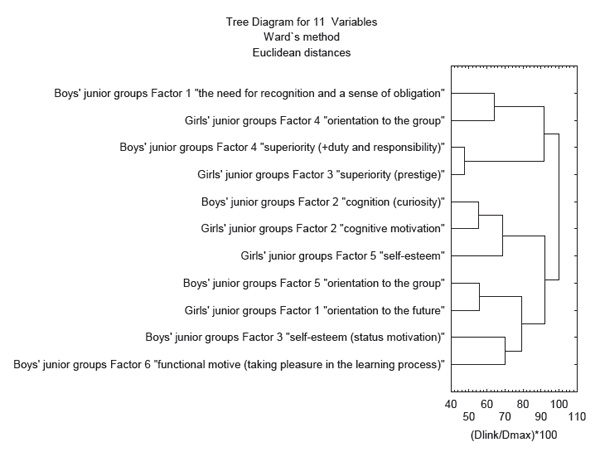

Gender features of motivation in the junior groups (Figure 4):

Figure 4. Gender features of motivation in the junior groups. Result of cluster analysis.

-

The motivation of superiority is partially similar (factor 4 for boys and 3 for girls). Apart from the general desire to know more than others, the boys affirm items about duty and responsibility to society, about the common obligation to be cultured and educated persons. Unlike the boys, for the girls the most important thing is to have others notice that they know much more than the other pupils.

-

The content of items that define cognitive motivation is close for girls and boys (factor 2 for both), but the girls' factor 5 is also close to them, defined as selfesteem through success in one's studies.

-

The girls have a motivation that determines their orientation to the future (factor 1), while the boys of the junior group do not show an analogous motivation — it is seen only in the senior group of boys.

-

There is also partial similarity between the items constituting factor 4 (affiliation, orientation to the peer group) for the girls and factor 5 (affiliation, aim at social approval) for the boys. Everybody likes classes where they can work in a group, to discuss the learning material. However, for the girls, unlike the boys, it is very important to receive good marks, to show their friends how successful they are. For the boys, the marks are not the main thing; it is more important to learn in a way that lives up to their parents' expectations.

-

For the boys of the junior group, factors 3 (self-esteem through status in the peer group) and 6 (functional motivation, orientation to the learning process) stand apart; they are more similar to each other than to the factors allocated to other groups. The girls have no similar factor profiles.

Gender features of motivation in the senior group:

-

There is similarity in the content of items that determine the motive of cognitive achievement: factor 1 for boys and factor 2 for girls. However, the boys often want to understand the class material as deeply as possible; they like difficult assignments and to overcome obstacles. For the girls, apart from a desire to learn new things, to find various ways of solving a problem, it is much more important to participate in events where they can assert themselves, to show that they are better than the others. Unlike the boys, it is very important for them to make others notice that they know, and know how to do, much more than everyone else.

-

There is also similarity in the items that determine affiliation (acceptance, respect, authority) for the boys (factor 3) and affiliation (need for social approval, to the extent to conformity) for the girls (factor 3). For the boys, academic success, apart from others' approval, also permits them to feel their own importance and dignity; good schoolwork allows them to increase their authority. Girls with analogous motivation study only in order to live up to the teachers' expectations, to win their friends' respect. At the same time, they do not like to discuss the schoolwork in a group of classmates, to defend their point of view.

-

Factors 2 for the boys and 1 for the girls are also similar: those that determine their orientation to the future. The boys' need to study is connected with their desire to live up to the expectations of their parents and society, to be appreciated as cultured and educated persons. Unlike the boys with the analogous motivation, for the girls the parents' approval is not so important. Older girls who are oriented to their parents' approval are allocated to a separate affiliation group (factor 4). Thus for the boys of the senior group, unlike the girls, the need to study for a successful future is inextricably intertwined with their parents' approval (and in that they are similar to the girls with the affiliation motivation – factor 4), while for the girls with an orientation to the future (factor 1), this is not paramount.

Figure 5. Gender features of motivation in the senior groups. Result of cluster analysis.

Discussion

We have revealed the gender and age specifics of the motivational attitude to studies, which is that as a child grows up, the orientation to the importance of learning becomes more and more generalized, with a stronger expression for boys than for girls. Girls of the junior group, unlike the boys of the same age with the motivation of self-esteem (who often try to study in order to gain the approval of adults and friends), assert themselves through academic success. Earlier it was shown (Sobkin & Kalashnikova, 2015) that with adolescent girls, the attitude towards schoolwork is determined by their desire to be successful at learning academic subjects, while with the boys the motivation is extrinsic (to occupy a certain position, to win praise and respect). This can be explained by the different social demands on boys and girls (because of attitudes and stereotypes), the feedback they receive from adults, and the special features of their education in Russian culture. Karabanova (2007) demonstrated that boys are more sensitive to the effect of a disharmonious style of upbringing.

Socialization of boys, as the majority of researchers agree (Tupitsina, 2004), is inconsistent, because the development and formation of the masculine identity involves feminization by the basic institutions of socialization, as well as the ambivalence of demands placed on growing boys: to be active and yet obedient, to be independent and yet to obey the rules, etc. Foreign psychological research on genderand age-stereotypes also show that differing expectations of teachers as well as parental expectations and attributions, influence the child's self-perception (Bern, 2004; Dweck & Davidson, 1978; Dweck & Bush, 1978) and adolescents' educational aspirations (Lazarides et al., 2016).

In our research, we found that the older girls with the motivation of achievement, unlike the boys with the analogous motivation, aim at distinguishing themselves from others in various ways. Their orientation to knowledge is supplemented by a desire to be noticeably distinguished from others, to draw special attention to themselves. As Vizghina and Pantileev (2001) have pointed out, while men feel "OK" with the importance of their own role and achievement of success when integrated into a group, women characteristically have the ability to present themselves emotionally and expressively, which attracts others' attention. An opposite motivation is observed with girls of the senior group, aiming at social approval, conformity (affiliation, factor 3). That motivation, besides the need for respect and approval, contains a dominating motive of avoidance (they are afraid of working in a group, to defend their point of view).

With the boys, the motivation of affiliation, besides approval and respect, is supplemented by their aspiration to occupy a rightful place among their fellows. It is also significant that the pragmatic motivation (to gain knowledge for a successful future) appears with boys only in the senior group and is inextricably connected to the parents' approval (like the girls with the affiliation motivation – factor 4), whereas for the girls with an orientation to the future (factor 1), it is not paramount; they more often than not think about what knowledge will be needed in the future, and which college they will attend. In other research (Vartanova, 2017), we found that girls also consciously connect pragmatic motives (a successful future) with the need to study well and values corresponding to that, which attests to a more mature perception of academic learning. For them the orientation to selfrealization (social and professional success in adult life) becomes of increasingly greater significance in the learning process.

Most boys perceive the learning process on the level of the self-assertive learning activity. The evidence shows that with boys an axiological vector of development is still at the level of motivation of affiliation and self-esteem (Obukhovsky, 2003).

Conclusions

We have found that age-related changes of motivation at the late secondary school age have a pronounced gender specificity, although one can also observe a common tendency of integration and generalization of its conceptual content.

For the senior boys, the content of the motivation of cognitive achievement is formed on the basis of two motives that are independent at the younger age: the motivation of curiosity and aiming at superiority (prestige). The motive of pragmatic orientation to the future for the senior boys consists of three motives that are independent at the junior age: self-esteem, obligation, and the functional motive of pleasure. The affiliation motivation is actually maintained intact.

For the girls, the motivation of cognitive achievement in the senior age group is based on the analogous motivation of the junior group, to which are added (as in the boys' group) the motives of superiority and self-esteem through success, which at the junior age were formed by independent factors. The motivation of pragmatic orientation to the future, observed in girls of the senior age group, was transformed from an analogous motive that was already fixed at the junior age. However, we can see not a fusion (supplement), but on the contrary, a shift of some of the perceived motivations to the affiliation factor. This testifies to a more "mature" motivation of the girls, their more rapid development. Moreover, the girls' affiliation motivations remain more differentiated, consisting, even at the senior age, unlike with boys, of two independent factors: the approval of a reference group of peers and the approval of the family and other adults.

Of course, the revealed features of the semantic attitude to learning are obtained on a limited sample of Moscow students and reflect only the actual state, while the reasons for their formation still require further study. Perhaps, the family (family values and gender stereotypes) influences the formation of the sense relation peculiarities. For high school students their teachers, as well as their closest social environment, can also play an important role. The question of the influence of national and cultural characteristics is no less important. All these questions were not the goals of this study; however, in the future the approach used in this paper seems to be applied to other groups of schoolchildren, formed according to the relevant criteria.

The revealed regularities also have practical significance. Understanding the qualitative singularity of the motives of students of different sex and age will allow realize more differentiated and effective psychological support of educational work in the school. Understanding these features is important for organizing a dialogue with the student in order to increase their motivation to study both from teachers and parents. That as a result will ensure the quality of the educational process.

Limitations

It is possible that other factors, such as personal and characterological traits and genetic predisposition, also affect the specifics of educational motivation, but these were not the focus of this article. It is also necessary to take into account that the patterns described here were identified only in a limited sample of Moscow students.

References

Arutiunova, K.R., & Alexandrov, Ju.I. (2016) Faktory pola i vozrasta v moral'noi otsenke deistvii [Gender and age factors in the moral appraisal of actions]: Psikhologicheskii zhurnal [Psychological journal], 37(2), 79–91. (In Russ.)

Babaeva, E.S. (2012). Osobennosti motivatsii ucheniya shkol'nikov v sovremennykh usloviyakh. Avtoref. diss. kand. psikol. nauk [Special features of motivation of studies of students in modern conditions]. [Ph.D. (Psychology) Thesis]. Moscow. (In Russ.)

Badmaeva, N.Z. (2006) Motivatsionnaya osnova razvitiya obshchikh umstvennykh sposobnostei. Diss. dokt. psikol. nauk [The motivational basis of development of general mental abilities]. [Sc. Doctoral (Psychology) dissertation]. Novosibirsk. (In Russ.) Bern, Sh. (2004). Gendernaya psikhologiya [Gender psychology]. St. Petersburg: EVROZNAK. (In Russ.).

Bozhovich, L.I. (2001). Problemy formirovaniia lichnosti: Izbrannye psikhologicheskie trudy [Problems of identity formation: Selected works in psychology]. (3rd ed.). Moscow: Moscow Psychological and Social Institute Publ.; Voronezh: MODEK RDC. (In Russ.).

Dotterer, A.M., McHale, S.M., & Crouter, A.C. (2009). The development and correlates of academic interests from childhood through adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(2), 509–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013987

Dweck, C.S., & Bush, E.S. (1978). Sex differences in learned helplessness: I. Differential debilitation with peer and adult evaluators. Developmental Psychology, 11, 147–156.

Dweck, C.S., Davidson, W., Nelson, S., & Enna, B. (1978). Sex differences in learned helplessness: II. The contingencies of evaluative feedback in the classroom and III. An experimental analysis. Developmental Psychology, 14, 268–276. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.14.3.268

Eccles, J.S., & Roeser, R.W. (2003). Schools as developmental contexts. In G. Adams (Ed.), Handbook of Adolescence (pp. 129–148). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Press.

Garcia-Lopez, L.J., Ingles, C.J., & Garcia-Fernandez, J.M. (2008). Exploring the relevance of gender and age differences in the assessment of social fears in adolescence. Social Behavior and Personality, 36, 385–390. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2008.36.3.385

Gordeeva, T.O. (2013) Motivatsiya uchebnoi deyatel'nosti shkol'nikov i studentov: struktura, mekhanizmy, usloviya razvitiya. Diss. dokt. psikkol. nauk [Motivation of learning activity of students: structure, mechanisms, conditions of development]. [Sc. Doctoral (Psychology) dissertation]. Moscow. (In Russ.)

Grouzet, F.M., Otis, N., & Pelletier, L.G. (2006). Longitudinal cross-gender factorial invariance of the Academic Motivation Scale. Structural Equation Modeling, 13, 73–98. https://doi. org/10.1207/s15328007sem1301_4

Ivannikov, V.A., Barabanov, D.D., Monroz, A.V., Shliapnikov, V.N. & Eidman E.V. (2014). Mesto ponyatiya volya v sovremennoi psikhologii [The place of the concept of "will" in modern psychology]: Voprosy psikhologii [Questions of psychology], 2, 15–23. https://doi. org/10.17347/3 (In Russ., аbstr. in Engl.).

Karabanova, O.A. (2007). Psikhologiya semeinykh otnoshenii i osnovy semeinogo konsul'tirovaniya [Psychology of family relations and basic concepts of family consulting]. Moscow: Gardariki. (In Russ.)

Kletsina, I.S. (2013). Sovremennoe sostoyanie i perspektivy issledovanii gendernykh otnoshenii v sfere sotsiologicheskogo i psikhologicheskogo znaniya [The contemporary situation and prospects of research on gender relations in sociology and psychology]. Zhenshchina v rossiiskom obshchestve. Rossiiskii nauchnyi zhurnal. ["Woman in Russian society". Russian scientific journal], 2 (67), 3–13. (In Russ.)

Kudinov, S.I. (1988). Polorolevye aspekty lyuboznatel'nosti podrostkov [Gender-role aspects of adolescent curiosity]. Psikhologicheskii zhurnal [Psychological journal], 19 (1), 26–36. (In Russ., аbstr. in Engl.)

Lazarides, R., Viljaranta, J., Aunola, K., Pesu, L., & Nurmi, J. (2016). The role of parental expectations and students' motivational profiles for educational aspirations. Learning and Individual Differences, 51, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.024

Leontiev, D.A. (1993). Sistemno-smyslovaya priroda i funktsii motiva [The systematic conceptual nature and functions of the motive]. Vestnik Moskovskogo Universiteta. Ser. 14. Psikhologiya [Moscow University herald, Ser. 14, Psychology], 2, 73–81. (In Russ.).

Lepper, M.R., Corpus, J.H., & Iyengar, S.S. (2005). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the classroom: Age differences and academic correlates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.184

Lupart, J.L., Cannon, E., & Telfer, J.A. (2004). Gender differences in adolescents' academic achievement, interests, values and life-role expectations. High Abilities Studies, 15 (1), 28– 39. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359813042000225320

Moscovitch, D.A., Hofmann, S.G., & Litz, B.T. (2005). The impact of self-construals on social anxiety: A gender-specific interaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 8, 659–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.021

Obukhovsky, K. (2003). Galaktika potrebnostei. Psikhologiya vlechenii cheloveka [The universe of needs. The psychology of human drives]. St. Petersburg: Izd. Rech. (In Russ.).

Otis, N., Grouzet, F.M.E., & Pelletier, L.G. (2005). Latent motivational change in an academic setting: A 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 170–183. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.170

Pavlova, T. S., & Kholmogorova, A. B. (2017). Psychological factors of social anxiety in Russian adolescents. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 10(2), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.11621/ pir.2017.0212

Peleg, O. (2012). Social anxiety and social adaptation among adolescents at three age levels. Social Psychology of Education, 15, 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-011-9164-0

Sobkin, V.S. & Kalashnikova, E.A. (2015). Dinamika motivatsionno-tselevykh transformatsii uchebnoi deyatel'nosti u uchashchikhsya osnovnoi shkoly [Dynamics of motivation-directed transformations of learning activities of middle school students]: Voprosy psikhologii [Questions of psychology], 3, 3–15. (In Russ., аbstr. in Engl.).

Tupitsina, I.A. (2004). Osobennosti gendernoi identichnosti starsheklassnikov v zavisimosti ot opyta vzaimootnoshenii so sverstnikami i sverstnitsami. [Special features of gender identity of upper-class students with reference to their experience of relationship with peers]. [Ph.D. (Psychology) Thesis]. St. Petersburg.

Vartanova, I.I. (2015). Motivatsiya i stil' atributsii starsheklassnikov [Motivation and style of attribution of senior pupils]: In D.B. Bogojavlenskaya (Ed.), Ot istokov k sovremennosti: 130 let organizatsii psikhologicheskogo obshchestva pri Moskovskom universitete: Sbornik materialov yubileinoi konferentsii: V 5 tomakh [From origins to the modern era: 130 years of organization of the psychological community at Moscow University: Proceedings of the anniversary conference, 5 vols.] (4, pp. 98–100). Moscow: Kogito-Centr. (In Russ.)

Vartanova, I.I. (2017). Psikhologicheskie osobennosti motivatsii i tsennostei u starsheklassnikov raznogo pola [Psychological features of motivation and values in high school students of different sexes]. Psikhologicheskaya nauka i obrazovanie [Psychological science and education], 22(3), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.17759/pse.2017220307 (In Russ., аbstr. in Engl.)

Vizghina, A.V., & Pantileev, S.R. (2001). Proyavlenie lichnostnykh osobennostei v samoopisaniyakh muzhchin i zhenshchin [Manifestation of personal features in self-descriptions of men and women]. Voprosy psikhologii [Questions of psychology], 3, 91–100. (In Russ., аbstr. in Engl.)

Walls, T.A., & Little, T.D. (2005) Relations among personal agency, motivation, and school adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97 (1), 23–31. https://doi. org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.1.23

Notes

1. The Russian term motivirovka is translated here as “perceived motivation.” A person’s actual “motive” is often not conscious, especially in the case of children. The “perceived motivation” is the way people try to express in words the reasons for their behavior. Our factor analysis used the perceived motivations (obtained from students’ answers to a questionnaire) to attempt to describe the actual motives (factors).

To cite this article: Vartanova I.I. (2018) Motivations of High School Students of Different Sex and Age. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 11 (3), 209-224

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.