Personal Sovereignty in Adolescents and Youth from Armenia, China, and Russia

Abstract

Background. In today’s hectic civilization, it is very important for a person to maintain personal boundaries which help him or her keep his/her identity. Personal sovereignty (PS) is a trait that demonstrates the extent to which a person’s empirical Self is respected by his/her social environment. Whereas the genesis and correlations system of personal sovereignty in proximal relationships have been investigated widely, little is known about whether they are culturally sensitive or not.

Objective. In this study, we aimed to investigate the patterns and genesis of personal sovereignty in relation to age and gender, by comparing individuals from Armenian, Chinese, and Russian cultures. Our sample consisted of 780 respondents, of whom 223 were from Armenia, 277 from China, and 280 from Russia; 367 were adolescents (Mage = 13) and 413 were youth (Mage = 21); there were 361 males and 419 females.

Method. The “Personal Sovereignty Questionnaire–2010” was used.

Results. The results suggest that culture, age, and gender all impact on the sense of personal sovereignty. Although there were no differences between cultures on the main PS score, we did find different PS patterns within all three cultures and when comparing males versus females. The PS scores in youth were higher than in adolescents, except in Armenia where the results were inverted. All age trends in PS were found in females, but not in males. Gender differences in PS within each culture were found in youth but not in adolescents.

Conclusion. We discussed and explained the outcomes with reference to the specificity of the way each culture endorses traditional or secular-rational values, which values determine the prevalent attitudes towards gender roles and demands on adolescents and youth.

Received: 30.10.2017

Accepted: 20.08.2018

Themes: Social psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2018_3/psych_3_2018_4_Nartova-Bochaver.pdf

Pages: 53-68

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2018.0304

Keywords: personal sovereignty, empirical Self, psychological space, culture, personal boundaries, values, gender roles

In its widest possible sense, however, a mans Self is the sum total of all that he CAN call his, not only his body and his psychic powers, but his clothes and his house, his wife and children, his ancestors and friends, his reputation and works, his lands and horses, and yacht and bank-account. All these things give him the same emotions.

William James, The Principles of Psychology

Introduction

Overpopulation and a very hectic environment represent some of the strongest challenges of contemporary society; thus, most people, especially those living in big cities, have to constantly share or distribute their resources, life spaces, and time. Hence, they try to take other people into account, and to protect their own identities and authenticity. This is why personal features and traits are required to help people defend their empirical Selves (James, 2013; Ingold, 2000; Schraube & Hojholt, 2015).

Previous research has emphasized different aspects of the empirical Self: personal space [1]; authenticity [2]; secrecy and self-concealment[3], personal things (Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton, 1981); and privacy (Altman, 1975; Westin, 1967; Wolfe, 1975). According to Westin, “privacy is the claim of individuals, groups or institutions to determine when, how, and to what extent the information about them is communicated to others” (1967, p. 7). Objects to be protected by privacy include territory, social contacts, and information. All of them contribute to the individuals sense of psychological well-being and social adaptation.

The concept of personal sovereignty.In the current study, we used the concept of personal sovereignty (PS) as the quality which links together all the parts of the empirical Self. In the authors opinion, personal sovereignty (souverain(French)-the carrier of the supreme authority) is the most crucial concept of both contemporary civilization and modern psychology.

As PS is a relatively new term, it is necessary to make some preliminary remarks on this topic. We consider a person to be a physical-territorial-existential integrity (Nartova-Bochaver, 2006, 2017). So, according to the modern non-Cartesian paradigm, every person not only reflects an “objective” reality, but also projects him/herself onto this reality, owns this being, and creates his own personalized sense of being in the world, “Dasein” (Lang, 1993). Mutual relationships between a person and his/her environment reflect the fact that a person constantly adopts things from the outside world, and alienates something from himself into his environment. Thus every individual has his/her own visible or invisible environmental “bubble” which can be described in terms of reality. Only the connection to his/her personal environment provides a person with a feeling of integrity and “ontological security” (Laing, 1960), and prevents self-alienation (Wood et al., 2008).

Contemporary psychologists inevitably use metaphorical concepts traditionally applied to the description of objective being. Whats more, concepts that originally had purely topological content, such as ‘space” (inner, psycho-semantic, social), “distance”, “above-below”, “nearer-further”, and “boundaries” find practical use in psychology (Bateson, 1972; Dorfman, 1976; Federn, 1929). The term “attachment” is also being used more broadly than previously; researchers talk about attachment to things and belongings, to place, home, and animals (Fine, 2010; Kleine & Baker, 2004; Reznichenko, Nartova-Bochaver, & Kusnetcova, 2016).

Thus we can conclude that personality has a complex mixed nature, and man can identify himself with different parts of reality. This allows psychologists, on the one hand, to study a personality by means of its environmental expressions and “behavioral residues” (Gosling et al., 2002), but, on the other hand, to research the personal boundaries defining where the personality is located in its multidimensional reality. In addition, this approach to personality as an empirical phenomenon is in line with the trend in contemporary psychology to maintain the ecological validity of research; as Lang (1993) stated, psychology should not investigate objects in artificial labor conditions but rather people with their possessions in their rooms. That is why it is very important to investigate the personal characteristics which participate in preserving the empirical Self. One of them is the sense of personal sovereignty.

There are several definitions of this phenomenon: 1) a persons ability to protect his/her psychological space; 2) a balance between a persons needs and the needs of other people; 3) the condition of personal boundaries; and 4) a system of explicit and implicit rules regulating relationships between people (Nartova-Bochaver, 2017). To sum up, personal sovereignty is a low-order trait demonstrating the extent to which a person can control his/her empirical Self.

Genesis of personal sovereignty.In accordance with the theory of personal sovereignty, its evolutionary and social aim is the maintenance of self-control by means of incorporating specific influences from outside. Initially sovereignty appears as a single persons answers to the situations he/she faces, as a result of coping with everyday deprivations, challenges, and stress. Later, it becomes a habit, and is transformed into a low-order trait by adolescence. After adolescence, personal sovereignty becomes a very important trait, which strongly contributes to a persons well-being and achievements. Thus, it is a generalization of the usual activities the person adopted against non-favorable influences which he/she faced (Silina, 2016a, 2016b). Moreover, every person aspires to keep or increase his/her level of personal sovereignty.

Structure of personal sovereignty.Based on theoretical analysis and psychotherapeutic cases, we identify six sovereignty domains: 1) body (BS); 2) territory (TS); 3) things (belongings) (TBS); 4) routine habits (RHS); 5) social contacts (SCS); and 6) tastes and values (TVS) (Nartova-Bochaver, 2008). Hence, every person has his/ her own preferences in these dimensions of psychological space, and can develop his/her own specific sovereignty pattern, or profile. In accordance with our theory, personal sovereignty depends on the persons real environment; it goes back to the territorial instinct and is a social form of a biological program. The family is a source of both invasions into one’s personal space and a strengthening of personal boundaries. If a child is developing in a friendly family atmosphere, and his/her wishes are respected and satisfied, the child has no need for extra defense, and her/his personal boundaries are kept whole and inviolate. To sum up, the level of personal sovereignty reflects the extent to which a family is ready to respect the growing child’s needs.Adaptive functions of personal sovereignty.A lot of empirical studies confirm that PS performs many adaptive functions in adolescence and youth. It contributes positively to self-esteem and self-representation, and is positively connected with authenticity and resilience, effective coping skills, and humanistic attitudes (Buravtsova, 2009; Kopteva, 2009; Panjukova, & Panina, 2006). It also predicts negatively non-chemical addictions, and prevents symptomatic depression and criminal behavior (Astanina, 2011; Bardadymov, 2012). Furthermore, sovereign people can more effectively communicate with others: sovereignty is positively connected with trust in the world, and negatively with avoidance and anxiety in close relationships (Nartova-Bochaver, 2014b). It has been found that sovereignty levels are higher in males than in females, and in youth as compared with adolescents (Nartova-Bochaver, 2017).

Finally, it has been shown that the protective function of sovereignty is strongest in youth and decreases in adults (Nartova-Bochaver, 2015). These dynamics are to be expected: by the time of their youth, people have adopted resources from outside, and sovereignty helps in doing that; but in adulthood, mature people undertake other developmental tasks and start giving resources back (Havighurst, 1972). At this developmental stage, they do not need the sovereignty trait as much as they did earlier. What’s more, to become mature adults, they first need to be sovereign youth.

An eco-psychological approach to personal sovereignty.Although the previous data were very impressive, they were collected in Russian culture only, and this serious limitation damages their representativeness. Cross-cultural research on personal sovereignty is in its infancy now, and there are few studies demonstrating its cultural specificity as relates to its content and dynamics (Martirosyan, 2014; Telegina, 2016). Why do we expect to find any cultural differences in sovereignty as a personal trait?

According to Bronfenbrenner (1986), a child grows up in a complex system of sub-environments, and the family, in turn, is influenced by the community and culture. Thus, the child’s sovereignty level may also indirectly depend on his/her culture: as Kagitqba^i stated (2013), the proximal environment (family) is always determined by a distal one (culture). It is culture which determines which parts of the empirical Self (and personal needs hidden behind them) are to be acknowledged and supported. Thus, cross-cultural study may uncover specific opinions about more or less important realities inherent in a culture.

As noted earlier, little is known about personal sovereignty in other cultures. To fill this gap, the current study investigates personal sovereignty profiles and dynamics during the transition from adolescence to youth depending on culture and gender. We have put forward the following hypothesis: Sovereignty patterns differ depending on culture, age, and gender.

To verify this hypothesis, we conducted an empirical study.

Methods

Our survey was carried out in Armenia, China, and Russia. These cultures were chosen for the following reasons. First, they all have a socialistic past and are collectivistic, which allows us to compare them. Secondly, they all have a long history of very tight business relationships, and there are many international families. At the same time, they have some features in common and some that diverge. [4] According to the World Values Survey (World Values Survey, n.d.), all endorse survival (not self-expression) values, which means they emphasize economic and physical security, a relatively ethnocentric outlook, and low levels of trust and tolerance. Armenia tends to maintain traditional values (stressing the importance of religion, parent-child ties, traditional gender roles and family values); China and Russia endorse secular-rational values (less emphasis on religion, traditional family values, and authority; acknowledgement of gender equality). Moreover, as gender roles and phenomena depend on the culture (Schmitt, Long, McPhearson, O’Brien, Remmert, & Shah, 2016), we predicted that there might be gender variance in the sovereignty level and patterns in Armenia, China, and Russia as well.

Measure.To measure the sovereignty level, the Personal Sovereignty Questionnaire-2010 (PSQ-2010) was used. It consists of six subscales and 67 items (NartovaBochaver, 2017).

The PSQ-2010 has some specific features: most items were taken from real psychotherapeutic clients’ stories describing traumatic life situations. Several statements were added into the pool by colleagues experienced in counseling, and by students studying environmental psychology and psychological counseling. According to the genesis of the sense of personal sovereignty, each item included a description of a real situation in the past and the person’s feelings about it. Hence, the outcome (i.e. increasing or decreasing sovereignty) is a result of the interaction between some provocative event and the person’s reflection on it.

For example, the statement “Even as a child I was sure nobody touched my toys when I was absent” can be evaluated by the respondent in several ways. First, he/ she can agree to it, saying “Yes.” Second, he/she could recall that he/she was sure somebody had touched the toys; in this case the answer was “No.” Third, the situation might not be relevant in his or her life at all; for example, if he had few toys and always kept them with him. In that case, there was no provocative situation, and the answer was “No.” The number of “Yes” responses to direct statements showed an increase in the sovereignty level; “No” responses showed a decreased level. “Yes” responses to direct items were marked “l”;“Yes” responses to reversed ones were marked “-1”. The more provocative the situations experienced by a person who cannot cope with this challenge (and which arouse his/her negative feelings), the less the person’s sovereignty level. Thus, both the absence of such situations in the life experience, and personal resistance against them, ensure psychological sovereignty.

The initial pool of these statements collected over the period of eight years initially included 102 items, and was divided into six subscales according to the six dimensions of the empirical Self (“Psychological space of the person”) listed above. After validation of the questionnaire, its six-factor structure was confirmed (Nartova-Bochaver, 2017).

Examples of PSQ items

-

I often felt offended when adults punished me with slapping and cuffing (BS).

-

I always had a place (table, chest, box), where I could hide my favorite things (TS).

-

It annoyed me when my mother shook my things out of the pockets before laundering (TBS).

-

I often became sad when I didn’t finish my play because I was called by my parents (THS).

-

My parents accepted that they didn’t know all of my friends (SCS).

-

I usually succeeded in having a children’s celebration as I liked (TVS).

Thus, by virtue of this questionnaire, we expected to assess the general sovereignty level and partial sub-scale scores in three cultures.

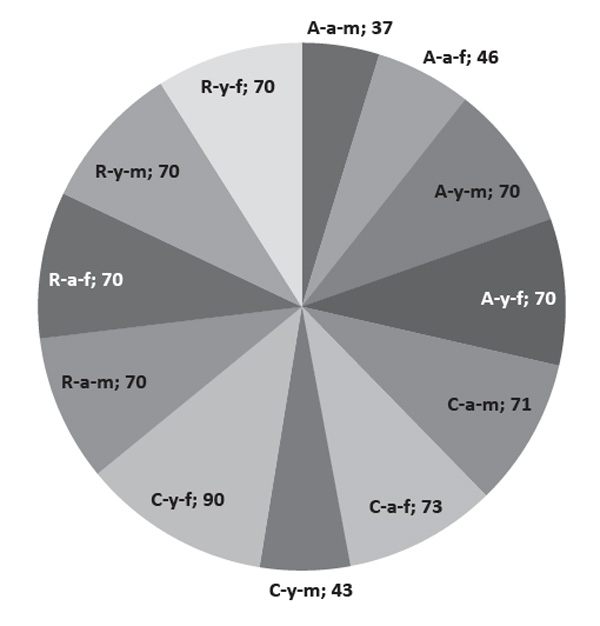

Sample.In total, 780 respondents participated in this survey: 223 from Armenia, 277 from China, and 280 from Russia; there were 367 adolescents (Mage= 13) and 413 youth (Mage= 21); there were 361 males and 419 females (seeFig. 1).The adolescents were recruited in Yerevan, Beijing, and Moscow; the youth (students) were recruited in Yerevan, Xiamen, and Moscow. The data were collected in class, partly via on-line services, and partly using the apencil-paper” procedure. Participation was voluntary, and participants were granted academic credits.

Figure 1. Structure of the sample.

Note. A=Armenia, C=China, R=Russia; a=adolescents, y=youth; m=males, f=females.

We have performed multifactorial multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) by means of Statistica 8, which was relevant to the correlational cross-sectional design of the study.

Results

First of all, it was shown that all of the supposedly independent variables (culture, age, and gender) significantly differentiated respondents by sovereignty level (see Table 1).Moreover, we found interesting interaction effects (for instance, Culture x Age and Gender x Age), although other effects were not significant.

Table 1

Multivariate Tests of Significance

|

Effect |

Test |

Value |

F |

Effect |

Error |

P |

|

Intercept |

Wilks |

0.49 |

133.15 |

6 |

763 |

0.000 |

|

Culture |

Wilks |

0.96 |

2.95 |

12 |

1526 |

0.000 |

|

Gender |

Wilks |

0.96 |

5.46 |

6 |

763 |

0.000 |

|

Age |

Wilks |

0.96 |

5.82 |

6 |

763 |

0.000 |

|

Culture x Gender |

Wilks |

0.99 |

1.10 |

12 |

1526 |

0.352 |

|

Culture x Age |

Wilks |

0.96 |

2.83 |

12 |

1526 |

0.001 |

|

Gender x Age |

Wilks |

0,97 |

3,60 |

6 |

763 |

0.002 |

|

Culture x Gender x |

Age Wilks |

0.98 |

1.52 |

12 |

1526 |

0.111 |

Table 2

Means and Standard Deviations of the PS Scores in Three Cultures

|

|

|

PS_main |

BS |

TS |

TBS |

RHS |

SCS |

TVS* |

|

Armenia |

M |

1.32 |

.13 |

.22 |

.14 |

.19 |

.32 |

.33 |

|

SD |

1.41 |

.38 |

.41 |

.33 |

.29 |

.41 |

.30 |

|

|

China |

M |

1.50 |

.16 |

.24 |

.20 |

.22 |

.29 |

.40 |

|

SD |

1.61 |

.36 |

.4C |

.37 |

.37 |

.36 |

.40 |

|

|

Russia |

M |

1.59 |

.22 |

.28 |

.22 |

.25 |

.33 |

.30 |

|

SD |

1.83 |

.44 |

.42 |

.40 |

.38 |

.42 |

.39 |

Note. *=differences are significant atp<.05.

PS_main-the main score of personal sovereignty; BS=body sovereignty; TS=territory sovereignty; TBS=things and belongings sovereignty; RHS=routine habits sovereignty; SCS=social contacts sovereignty; TVS=tastes and values sovereignty

Culture. Acomparison of the three cultures showed that, despite the absence of differences in the main sovereignty scores, there were differences in tastes and values sovereignty (the highest in China, F(2,768) = 3.69, p = .025) as well as two tendencies: in body sovereignty (the highest in Russia, F(2,768) = 2.80, p = .061), and in the things and belongings sovereignty (the lowest in Armenia, F(2,768) = 2.75, p = .064) (see Table2).

Age.In line with the results from Russia, the main sovereignty score was higher among youth (F(l, 768) = 6.68, p = .009) due to the territory sovereignty (F(l, 768) = 17.64, p = .000), and time habits sovereignty (F(l, 768) = 20.03, p = .000) (see Table 3).

Table 3

Means and Standard Deviations of the PS Scores in Adolescents and Youth

|

|

|

PSmain* |

BS |

TS* |

TBS |

RHS* |

SCS |

TVS |

|

Adolescents |

M |

1.30 |

.15 |

.18 |

.18 |

.16 |

.30 |

.32 |

|

SD |

1.66 |

.42 |

.42 |

.38 |

.34 |

.40 |

.38 |

|

|

Youth |

M |

1.65 |

.19 |

.30 |

.20 |

.28 |

.32 |

.36 |

|

SD |

1.61 |

.38 |

.39 |

.37 |

.35 |

.40 |

.37 |

Note. *= differences are significant at p<.01.

Gender. In the whole sample, we found no differences in the main sovereignty scores, but the territory sovereignty was higher in males (F(l, 766) = 6.12, p = .013), whereas the time habits and value sovereignty scores were higher in females (respectively, F(l, 766) = 5.22, p = .023; F(l,766) = 6.43, p = .Oil) (see Table 4).

Table 4

Means and Standard Deviations of the PS Scores in Males and Females

|

|

|

PSmain |

BS |

TS* |

TBS |

RHS* |

SCS |

TVS* |

|

|

M |

1.50 |

.20 |

.28 |

.21 |

.19 |

.33 |

.30 |

|

Males |

||||||||

|

|

SD |

1.62 |

.39 |

.41 |

.37 |

.36 |

.41 |

.35 |

|

|

M |

1.47 |

.15 |

.22 |

.18 |

.25 |

.29 |

.38 |

|

Females |

||||||||

|

|

SD |

1.67 |

.40 |

.41 |

.37 |

.35 |

.39 |

.38 |

Note. *=differences are significant at p<.05

Then, as we have significant interaction effects of factors, we performed an analysis of variance for each of the variable complexes in order to study how stable the sovereignty differences were.

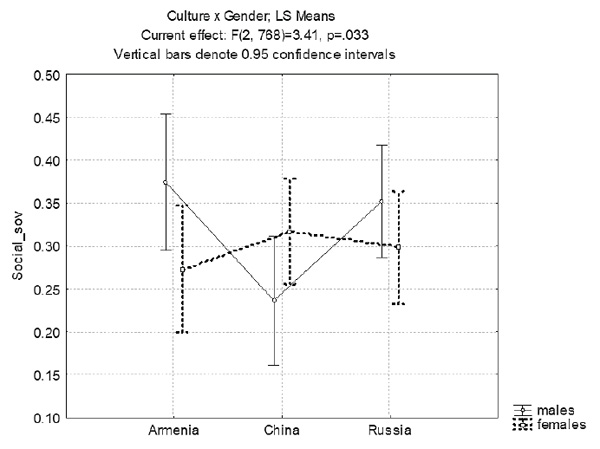

Culture x Gender. Despite the fact that the general model did not show any effects, we uncovered one partial difference: whereas in Armenia and Russia the social contacts sovereignty score was higher in males, in China this composition was reversed, and female respondents had higher scores (F(2,768) = 3.41, p = .033) (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.The social contacts sovereignty in three cultures

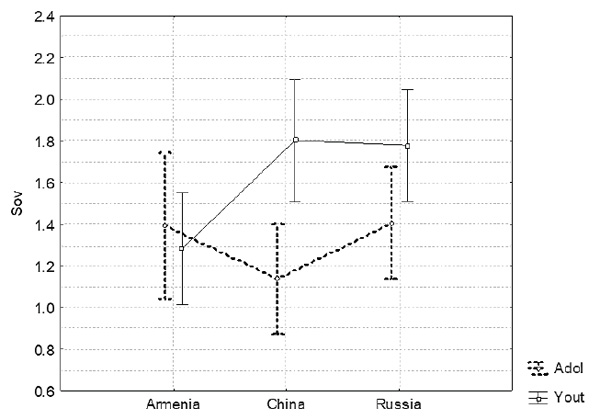

Figure 3. The main sovereignty scores in three cultures.

Culture x Age. As the general model showed significant interaction effects, they were analyzed in detail. We found that the sovereignty level increased with age in China and Russia, but not in Armenia (F(2, 768)=3.31, p=.037) (see Fig. 3).This trend was due to the impacts of body sovereignty (F(2,768)=4.64, p=.009) and time habits sovereignty (F(2, 768)=6.97, p=.001).

Gender x Age. Our analysis showed that gender differences in the sovereignty scores don t show up in adolescents, but are very salient in youth, due to a critical increase in thing and belonging sovereignty among females, and a simultaneous decrease among males (F(2,768) = 10.19, p = .001). In addition, values sovereignty didn’t differ between male and female respondents in adolescence, but in youth, it was higher in young women (F(2,768) =4.31, p = .038).

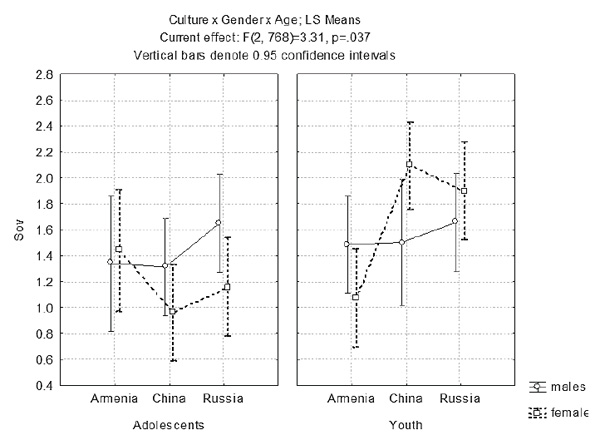

Figure 4. The main sovereignty scores in groups “Culture x Gender x Age”.

Culture x Gender x Age. Finally, since the main factors of culture, age, and gender often "extinguished” each other, we analyzed the effects of interaction between all three variables. The lowest main sovereignty scores were found in female adolescents from China and female youth from Armenia, and the highest ones were revealed in female youth from China and Russia (F(2,768) = 3.30, p = .037) (seeFig. 4).This trend resulted from the impact of the social sovereignty: whereas in adolescence it didn’t differ groups, in youth there is a divergence between males and females: the lowest score was in female respondents, and the highest one in males (F(2,768) = 3.74, p = .024) (see Table 5).

Table 5.

|

| PSmain* | BS | TS | TBS | RHS | scs* | TVS |

A-a-m | M | 1.34 | .16 | .18 | .15 | .18 | .34 | .33 |

SD | 1.29 | .46 | .40 | .28 | .27 | .38 | .25 | |

A-a-f | M | 1.44 | .22 | .12 | .13 | .23 | .38 | .36 |

SD | 1.24 | .34 | .35 | .32 | .27 | .43 | .31 | |

A-y-m | M | 1.49 | .17 | .30 | .15 | .15 | .41 | .31 |

SD | 1.61 | .38 | .40 | .39 | .37 | .34 | .38 | |

A-y-f | M | 1.07 | .03 | .21 | .13 | .21 | .17 | .33 |

SD | 1.80 | .37 | .43 | .39 | .35 | .40 | .45 | |

C-a-m | M | 1.31 | .13 | .20 | .28 | .14 | .26 | .29 |

SD | 1.65 | .45 | .46 | .36 | .35 | .41 | .35 | |

C-a-f | M | .96 | .05 | .08 | .10 | .07 | .29 | .36 |

SD | 1.92 | .47 | .44 | .42 | .36 | .42 | .41 | |

C-y-m | M | 1.50 | .20 | .34 | .17 | .24 | .21 | .35 |

SD | 1.46 | .34 | .41 | .36 | .32 | .40 | .30 | |

C-y-f | M | 2.10 | .25 | .34 | .24 | .39 | .34 | .53 |

SD | 1.51 | .39 | .42 | .34 | .28 | .40 | .33 | |

R-a-m | M | 1.65 | .24 | .31 | .27 | .16 | .32 | .34 |

SD | 1.42 | .32 | .36 | .37 | .34 | .41 | .36 | |

R-a-f | M | 1.16 | .15 | .17 | .12 | .21 | .25 | .26 |

SD | 1.35 | .32 | .36 | .33 | .32 | .32 | .35 | |

R-y-m | M | 1.65 | .26 | .33 | .18 | .28 | .38 | .22 |

SD | 1.99 | .41 | .41 | .42 | .42 | .47 | .40 | |

R-y-f | M | 1.90 | .23 | .30 | .30 | .36 | .34 | .37 |

SD | 1.69 | .43 | .38 | .38 | .36 | .38 | .38 |

Note. See legends to Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Discussion

Our results show that, as expected, culture, age, and gender predict sovereignty level, patterns, and dynamics, but these connections are not linear: these variables interplay. That is why it is necessary to describe each culture separately.

Contrary to our prediction, the sovereignty level did not differ among the three cultures. This impressive result confirms the evolutional and adaptive function of the sovereignty trait in everyday lives. It is no surprise that all cultures need and support its development; however, the sovereignty patterns and dynamics differed widely. In Russia, body sovereignty (natural needs for comfort, denial of asceticism, keeping preferred dietary identity) is a very important value which is passed from the society to the family. In Armenia, there is a denial of private possessions, shown by the things and belongings sovereignty scores being lower than in China and Russia. This reflects the fact that an obligation to share ones belongings with other people is common in this culture. Finally, in China the sovereignty profile reflects the importance of defending ones tastes, values, and worldview in general.

While analyzing the highest scores in the sovereignty profile, we identified the typical resources of empirical Self (for each culture). In Armenia these were social contacts and the values. Indeed, Armenian people appreciate social relationships, friendship, family, and hospitability very much, and, at the same time, are proud of their sense of beauty, faith in Christianity, and long history. All these values are equally inherent in Armenian identity. In China, we found the highest scores in the same areas, but more in tastes and values sovereignty than in social contacts. This means that preferences, opinions, and worldview in general are the most important values. Along with social contacts (in full accordance with the Confucian philosophy now popular in China), they form the very base of Chinese cultural identity. Finally, in Russia the leading position was in social contacts sovereignty rather than in tastes and values. In addition, the third most important PS area in all three cultures was taken up by territory sovereignty. Thus, Armenians, Chinese, and Russians present themselves as hospitable and spiritual, but at the same time are strongly attached to their (large or small) land; all of these aspects form their sense of identity.

Furthermore, we found interesting ambiguous differences concerning age. Youth are on average more sovereign than adolescents: they get their private territory and opportunity to arrange their time. Naturally, society respects youth more than adolescents, and provides them with more freedom.

On the other hand, this finding concerned only the female group, and only in China and Russia. As these cultures endorse secular-rational values, including an acknowledgement of gender equality, it is no surprise that young women get more sovereignty. This increase is especially strong in China, in contrast to the very low sovereignty level of girls. As for Armenia, which endorses traditional values, the decrease in the sovereignty level seems to be related to traditional attitudes toward women: whereas Armenians are fond of their children, they are very demanding of young women whose everyday lives are accompanied by many restrictions. These restrictions are connected with limitations on social contacts sovereignty, which, in turn, may be influenced by Armenian traditions of match-making and marriage.

As for the stability of PS scores in male groups in all three cultures, it seems to be connected, first, with the variation by gender of many personal features (according to Geodakyan (1989), females are more varied in their phenomena), and, secondly, with the variety of social demands and restrictions on males, including conscription. Boys and young men accept these demands from early childhood and become ready to answer them, even at the cost of their freedom.

The gender differences in the sovereignty profiles demonstrate that girls and young women (on average) have much more freedom than boys and young men in arranging their daily schedule and expressing their own tastes and preferences. But boys and men are freer to have their own private territories, space, and places. Society and culture permit and support these forms of personal sovereignty. At the same time, gender differences in sovereignty are, in turn, influenced by age. In adolescence, social demands on both girls and boys are similar, and there are no significant differences in their sovereignty features. These results are also in full agreement with the outcomes of David Schmitt, who discovered that in traditional cultures, gender roles contrast greatly, but psychological phenomena do not (Buss & Schmitt, 2011). In youth, social expectations become more varied, taking into account social representations of gender roles; maturing youth accept these expectations and adapt to them, which is reflected in their personal sovereignty levels and patterns. In addition, our sample was drawn from students, who, as the most progressive group of youth, no doubt endorse Western values of universalism and globalization. That is why gender differences in sovereignty increase with age.

Finally, when comparing culture x age x gender groups, we found the lowest sense of personal sovereignty in Chinese girls and Armenian young women. This gives evidence of the unequal value of a child (depending on his/her gender) in China: boys have more freedom, and their personalities and wishes are more respected than girls. In Armenia, young women are subject to control and restrictions from society, in line with traditional attitudes toward gender roles. As for the highest levels in sovereignty, they were found in Chinese and Russian young women. This result could be interpreted in the following way. First, young Chinese female students are a special group of youth who demonstrate a very high level of resilience and competitiveness, because entering university is a very difficult social and intellectual task requiring a lot of personal sovereignty. As for Russian young women, their high scores may be, first, a result of Russian history, as Russia has a culture where women have had a lot of social rights for many years; secondly, women in Russia do have not as many social restrictions as men do.

Limitations

We would like to point out some limitations of this study. First, the youth sample consisted of students, and was not randomized by SES and region. This should be corrected in future surveys. Second, our work did not use tools other than the PSQ2010. In the future, the sense of personal sovereignty in these three cultures should be investigated together with other measures of well-being parameters. Finally, it might be very promising to include other cultures.

Conclusion

To sum up, our hypothesis was confirmed. As expected, the sovereignty patterns differed depending upon the culture: in addition, age and gender contributed to these differences. In general, the sovereignty level increased with age, mainly thanks to the female groups. In Armenia, on the contrary, in female groups, the sovereignty level decreased.

Why have we received these outcomes? Culture determines attitudes toward individual sovereignty. In Armenia, family values and an empathic style of parenting stimulate sovereignty in adolescents, but in China and Russia gender nonequality prevents personal sovereignty at this age. Furthermore, winning in social competition (because our youth were students at prestigious universities) stimulates the sense of personal sovereignty in youth from China and Russia, whereas social demands (e.g., conscription) inhibit personal sovereignty in young men from Armenia, China, and Russia.

These outcomes may be useful in setting up personal growth programs, ethnopsychological and educational research, and in social practice.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the volunteers who took part in our study. We very much appreciate Mrs. Xiangqin Shen for her help in data collection in Beijing. This research was partially supported by Russian Foundation of Basic Research (Project 16-06-00239 by S. Nartova-Bochaver).

References

Altman, I. (1975). The environment and social behavior. Privacy, personal space, crowding.Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Astanina, N.B. (2011). Osobennosti fenomena doveriya и nesovershennoletnih pravonarushitelej muzhskogo pola[Specificity of trust phenomenon in criminal male adolescents] .Thesis of PHD dissertation. Moscow.

Bardadymov, V.A. (2012). Autentichnosf lichnosti podrostkov na raznyh stadiyah addiktivnogo povedeniya[The personal authenticity in adolescents being at different stages of additions]. Thesis of PHD dissertation. Moscow.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental psychology, 22(6),723-742. https://doi:10.1037/00121649.22.6.723

Buravtsova, N.V. (2009). Strukturno-soderzhaternye harakteristiki psihologicheskogo prostranstva lichnosti studentov gumanitarnoj napravlennosti [Structural-content characteristics of the psychological space in humanitarian students]. Izvestija Rossijskogo gosudarstvennogo pedagogicheskogo universiteta im. A.I. Gercena, 113,260-264.

Buss, D.M., & Schmitt, D.P. (2011). Evolutionary Psychology and Feminism. Sex Roles,64, 768787. https://doi:10.1007/sl 1199-011-9987-3

Csikszentmihalyi, M. & Rochberg-Halton, E. (1981). The meaning of things: domestic symbols and the self.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi/:10.1017/CBO9781139167611

Dorfman, L.Ja. (1996). Voplowenija i prevrawenija как formy vzaimodejstvija individualhosti s mirom [Embodiments and transformations as forms of human interaction with the world]. In Ahutin, A.V., & Sobkin, V.S. Gumanitarnaja пайка v Rossii: Sorosovskie laureaty (pp. 187-199). Vol. 1. Psihologija. Filosofija.Moscow: Mezhdunarodnyi nauchnyi fond.

Federn, P. (1929). Das Ich als Subjekt und Objekt im Narzissmus [The ego as subject and object in Narcissism]. Internationale Zeitschriftfuer Psychoanalyze, 15,393-425.

Fine, A.H. (Ed.). Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice.Boston: Academic Press, 2010.

Finkenauer, C., Engels, R.C.M.E., Branje, S.J.T., & Meeus, W. (2004). Disclosure and Relationship Satisfaction in Families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66,195-209. https://doi:10.111 l/j.0022-2445.2004.00013.x-il

Geodakyan, V.A. (1989). Teoriya differenciacii polov v problemah cheloveka [Theory of gender differenciation in man’s problems]. In Chelovek v sisteme nauk(pp. 171-189). Moscow: Nauka.

Gosling, S.D, Ко, S.J., Mannarelli, T., & Morris, M.E. (2002). A room with a cue: personality judgments based on offices and bedrooms // Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(3).P. 379-398. https://doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.379

Havighurst, R.J. Developmental tasks and education.N.Y.: McKay, 1972.

Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment. Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill.L.; N.Y.: Routledge. https://doi: 10.4324/9780203466025

James, W. (2013). The principles of psychology.Read Books Ltd. Retrived from: http://bookre.org/reader?file=660643

Kagitcibasi, C. (2013). Family, self, and human development across cultures: Theory and applications.London: Routledge.

Kleine, S.S., & Baker, S.M. (2004). An Integrative Review of Material Possession Attachment. Academy of Marketing Science Review [Online], 1.Retrieved from: http://www.amsreview.org/articles/kleine01 -2004.pdf

Kopteva, N.V. (2010). Ontologicheskaja uverennost” i psihologicheskaja suverennost” [Ontological confidence and psychological sovereignty]. Mir nauki, kuFtury, obrazovanija, 22, 223-227.

Laing, R.D. (1960). The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness.Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Lang, A. (1993). Non-Cartesian Artefacts in Dwelling Activities: Steps towards a Semiotic Ecology. Schweizerische Zeitschrift fiir Psychologie, 52,138-147.

Martirosyan, K.V. (2014). Ehtnospecifichnost’ suverennosti psihologicheskogo prostranstva lichnosti [Ethnospecificity of the sovereignty of the personal psychological space]. Sovremennye problemy nauki i obrazovaniya,6, 1530. Retrived from: https://elibrary.ru/download/elibrary_22878845_24795510.pdf.

Nartova-Bochaver, S. (2006). The Concept “Psychological Space of the Personality” and Its Heuristic Potential. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 44,85-94. https://doi: 10.2753/RP01061-0405440506

Nartova-Bochaver, S. (2017). Psihologiya suverennosti: desyaf let spustya[Psychology of sovereignty: ten years later]. M: Smysl.

Nartova-Bochaver, S.K. (2014). Psihologicheskaya suverennost’ i osobennosti mezhlichnostnogo obshcheniya [Psychological Sovereignty and Interpersonal Interaction Specificity]. Social Psychology and Society,(3), 42-50.

Nartova-Bochaver, S.K. (2015). Psihologicheskaya suverennost’ как prediktor ehmocional’noj ustojchivosti v rannej i srednej vzroslosti [Psychological sovereignty as a predictor of the emotional resistance in earlier and middle adulthood]. Clinical psychology and special education, 4(1),15-28.

Panjukova, Ju.G. & Panina, E.N. (2006). Suverennost’ psihologicheskogo prostranstva lichnosti podrostkov-pravonarushitelej как faktor udovletvorennosti kachestvom zhizni [Sovereign-

ty of the personal psychological space as a factor of criminal adolescents’ satisfaction with the quality of life]. Aktualnye problemy borby s prestupnosfju v Sibirskom regione:sbornik materialov mezhdunarodnoj nauchnoj konferencii,294-297. Krasnoyarsk: Siberian Justice Institute of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Reznichenko, S.I., Nartova-Bochaver, S.K., & Kusnetcova, V.B. (2016). Metod ocenki privyazannosti к domu [The Instrument for Assessment of Home Attachment]. Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 13(3),498-518.

Robinson, O.C., Dunn, A., Nartova-Bochaver, S., Bochaver, K., Asadi, S., Khosravi, Z., ..., & Yang, Y. (2016). Figures of admiration in emerging adulthood: a four-country study. Emerging Adulthood, 4(2),82-91. https://doi:10.1177/2167696815601945 Robinson, O.C., Lopez, F.G., Ramos, K., & Nartova-Bochaver, S. (2013). Authenticity, social context, and well-being in the United States, England, and Russia: a three country comparative analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(5),719-737. https://doi:10.1177/0022022112465672 Schraube, E. & Hojholt, C. (Eds.). (2015). Psychology and the conduct of everyday life.London: Routledge.

Silina, O.V. (2016a). Granicy Ya i psihologicheskoe blagopoluchie detej 2-10 let [The “Г Boundaries and the Psychological Well-Being of Children Aged 2-10]. Clinical psychology and special education,5(3), 116-129. https://doi: 10.17759/psyclin.2016050308 Silina, O.V. (2016b). Struktura granic Ya u detej 2-10 let [The structure of the boundaries I for children 2-10 years]. Social Psychology & Society,7(4), 83-98. https:// doi: 10.17759/sps.2016070406

Sommer, R. (1959). Studies in personal space. Sociometry, 22,281-294. https://doi:10.2307/2785668 Telegina, S.Ya. (2016). Osobennosti suverennosti psihologicheskogo prostranstva u russkih, evrejskih i tatarskih podrostkov [Specificities of the personal psychological sovereignty in Russian, Tatar, and Jewish adolescents]. Vestnik SPb. gos. universiteta. Seriya 16. Pedagogika i psihologiya, 16(4),146-157.

Westin, A.F. (1967). Privacy and freedom.New York: Atheneum.

Wismeijer, A.A.J. (2008). Self-Concealment and Secrecy: Assessment and Associations with Subjective Well-being.Tilburg: Tilburg University.

Wolfe, M. (1978). Childhood and privacy. In I. Altman & J. Wohlwill (Eds.), Children and the Environment(pp. 175-222). New York: Plenum Press. https://doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3405-7_6 Wood, A.M., Linley, P.A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: a theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the authenticity scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology,55(3), 385-399. https://doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.385World Values Survey (n.d.). Retrived from http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jspWu, M.S., Schmitt, M., Nartova-Bochaver, S., Astanina, N., Khachatryan, N., Zhou, C., & Han, B. (2014). Examining self-advantage in the suffering of others: cross-cultural differences in beneficiary and observer justice sensitivity among Chinese, Germans, and Russians. Social Justice Research (SORE), 27(2),231-242. https://doi: 10.1007/sll211-014-0212-8

Notes

1. Gosling, Ко, Mannarelly, & Morris, 2002; Sommer, 1959); authenticity (Robinson, Lopez, Ramos, & Nartova-Bochaver, 2013; Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis, & Joseph, 2008.

2. Robinson, Lopez, Ramos, & Nartova-Bochaver, 2013; Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis, & Joseph, 2008.

3. Finkenauer, Engels, Branje, & Meeus, 2004; Wismeijer, 2008.

4. Robinson, Dunn, Nartova-Bochaver, Bochaver, Asadi, Khosravi, Jafari, Zhang, & Yang, 2016; Wu, Schmitt, Nartova-Bochaver, Astanina, Khachatryan, Zhou, & Han, 2014.

To cite this article: Nartova-Bochaver S.K., Hakobjanyan A., Harutyunyan S., Khachatryan N., Wu M.S. (2018) Personal Sovereignty in Adolescents and Youth from Armenia, China, and Russia. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 11 (3), 53-68

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.