Studying anti-vaccination behavior and attitudes: A systematic review of methods

Abstract

Immunization is one of the most significant achievements of public health over the last 100 years. Recently, however, people have been increasingly refusing to vaccinate. There are a large number of separate studies on how pervasive this behavior is and what fac- tors influence it, but no systematic review has been undertaken so far that looked at these studies as a whole. To conduct an analysis of studies that examine vaccine refusal and negative attitudes towards vaccination, focusing on the methodological approaches to the study of these problems and evaluation of their quality. A systematic review of English-language studies published between 1980 and 2015, using the Web of ScienceTM Core Collection database. The final review dealt with 31 papers. The studies in question were mainly conducted in North America and Western Europe. They were published three years after conclusion, on average. We have identified five different approaches to the study of these problems: 1) studies of parents’ attitudes and behavior; 2) analysis of vaccination records; 3) studies of attitudes and behavior among the general population; 4) studies of medical professionals’ attitudes, behavior, and experience; and 5) others. We found that theoretical models were not commonly used at the planning stage, while the studies also lacked a common approach to the operationalization of vaccine refusal, as well as of negative attitudes towards vaccination. Several promising directions have been identified for future studies on vaccine refusal and negative attitudes towards vac- cination.

Received: 21.01.2016

Accepted: 05.10.2016

Themes: Psychology and bioethics; Clinical psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2017_1/psych_1_2017_13.pdf

Pages: 178-197

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2017.0113

Keywords: vaccination, vaccine refusal, attitudes towards vaccination, systematic review

Introduction

Immunization is one of the most significant achievements in public health over the last 100 years (glanz et al., 2013). Recently, however, the science community has been concerned about dropping rates of vaccination globally, caused not so much by a lack of resources as by informed refusal to vaccinate (e.g.; Omer et al., 2006; Daniels et al., 2001).

Today, insufficient commitment to vaccination is commonly viewed as being within the framework of the continual model, whereby the extremes are represented, respectively, by vaccine acceptance and vaccine refusal/rejection, while intermediate forms include various cases of so-called vaccine hesitancy in the sphere of decision-making about vaccination (Larson, 2014). This hesitancy includes multiple behavioral strategies toward preventive vaccination and looking for an alternative vaccination schedule (Saada А. et al., 2015), including selective delay/refusal, late vaccination (Benin et al., 2006; gust D. A. et al., 2008; Dempsey et al., 2011), or just cautious acceptance while expressing doubts when consenting to vaccination (Leask et al., 2012).

Because this phenomenon has so many different manifestations, empirical studies thereof differ in their methodological basis, as well as in their subject matter. The latest attempts to summarize diverse empirical studies include a review by Larson et al. (2014) regarding vaccine hesistancy phenomena; one by Falagas and Zarkadoulia (2008) focusing on suboptimal compliance with vaccination requirements for children in developed countries only; and a paper by Quadri-Sheriff et al. (2012) looking at the personal motivations behind decisions on immunization— the idea of herd immunity.

There are two main conceptual differences between this study and those mentioned above:

- The focus of our analysis is on the extreme of the vaccine hesitancy continuum, i.e. on the phenomenon of vaccine refusal. We believe that it is this particular aspect of vaccine hesitancy that is the most interesting from the public health point of view, both practically and scientifically. Moreover, vaccine refusal might be characterized by a different set of factors than other types of vaccine hesitancy; therefore, such studies should, perhaps, be analyzed separately.

- This paper looks at the methodological basis underlying studies of vaccine refusal, rather than trying to analyze their results. The existing systematic reviews offer but a superficial look at the design and methods of vaccine refusal studies. A systematic review of the methodological basis of such studies will allow the identification of their main deficiencies, as well as offering some insights into developing new approaches. Also, this type of analysis is indispensable for those countries and researchers who are just beginning to examine these problems (thus, we were able to find but a few recent studies of this kind conducted in Russia (Antonova et al., 2014; Elukova, 2015).

Method

To describe the methodological approaches to analyzing the vaccine refusal problem, the systematic review method was used. The review included papers on social or medical issues published between 1980 and 2015 in peer-reviewed journals, and containing the empirical results of the original studies.

Paper search algorithm

The search for the papers was conducted in the fall of 2015, using the Web of Science TM Core Collection electronic bibliography database.

The following criteria were used for including a source in the study:

- Publications had to be in English;

- The publication date had to be between January 1, 1980, and October 1, 2015;

- Data on the methods and results of an empirical study of the vaccine refusal phenomenon among any population group had to be available;

- The studies had to focus on attitudes/behavior leading to the rejection of all or most vaccines (but not any one specific vaccine) for oneself and/or one’s children.

The following criteria were used to exclude a study from the review:

- The studies focused on attitudes/behavior concerning

specific vaccines.

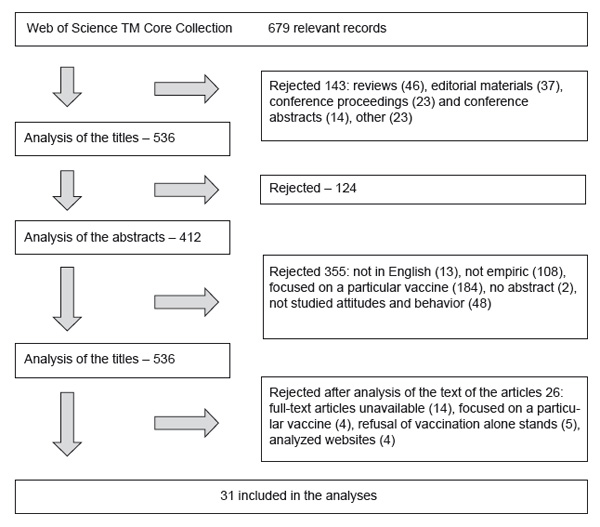

In the process of working with the Web of Science™ Core Collection electronic bibliography database, the following search sequence was used: (antivaccin*) or (anti-immuniz*) or (vaccin* near/3 refus*) or (vaccin* near/3 denial*) or (antivaccin*), and “1980” [Date - Publication]: “2014” [Date - Publication]. A total of 679 entries were found, among which were 536 relevant papers. After an assessment of the correspondence of the title and abstract to the search criteria, 479 of these papers were rejected. After a review of the correspondence of the complete publication text to the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the remaining 57 studies, the final corpus included 31 publications which contained materials of original studies of the vaccine refusal phenomenon (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the step-bystep search algorithm that was applied.

Results

Timeframe

The papers that were included in the analysis were published between 2002 and 2015. At the same time, we did not detect any periods where there was a particular surge of interest in these problems: Starting in 2008, every year saw the publication of 2-4 papers on the subject that met the inclusion criteria. On average, it took about three years from the data collection stage to the date of publication (M=3.12; min=1; max=8).

Country of study

An overwhelming majority of the studies (21=68%) were conducted in the United States. Another 7 studies (23%) were conducted in Western Europe (mostly in the Netherlands). A significant contribution was also made by Canadian researchers (3=10%). The only study conducted outside North America or Western Europe was conducted in Bangladesh.

Study design

An overwhelming majority of the studies used the quantitative approach (23=74%). Two of the studies combined qualitative and quantitative methods.

Among the quantitative studies, the largest group was represented by those that were conducted using a cross-sectional design (19). Other research designs were much rarer: three experimental studies were found, as well as one retrospective matched cohort study and one case-control study[1].

The majority of the quantitative studies (15 out of 23=65%) used multivariate methods for statistical analysis; however, a third of the studies (5=22%) used only bivariate methods to describe correlations between vaccine refusal and other variables; alternatively, data was described using descriptive statistics only (2=9%).

Nine of the reviewed studies (26%) used only qualitative methods.

On the whole, we can identify several independent types of studies looking at vaccine refusal and its factors.

1. Studies of parents’ attitudes and behavior

This group includes both qualitative and quantitative studies, which focused, above all, on examining parents’ behavior and attitudes regarding vaccination of their children, and which used self-reporting. This group makes up the majority of the studies found (20=65%). The groups were highly heterogeneous in terms of children’s ages: Some researchers focused on parents of very young children, at the age when the greatest number of planned vaccinations occur; others used a much broader timeframe. The latter approach, however, can be slightly more susceptible to criticism. The fact that vaccination primarily occurs at a young age may compromise parents’ ability to remember the conditions under which their children, who are older now, were to be vaccinated.

The data from such studies was often collected using samples representative of individual regions or even countries, and their size in some cases reached as many as 11,000 people. It should be noted that using large samples could often be justified under such an approach. The proportion of parents who report complete or partial vaccine refusal can be rather small, so the sample size determines whether the researchers will be able to examine the defining characteristics of a given subpopulation. In some studies (e.g., Dempsey et al., 2011), the authors say directly that a more thorough analysis of a group of individuals refusing vaccines was deemed impossible due to statistical requirements.

A number of researchers used special techniques to overrepresent the parents who refused, or had negative attitudes towards, vaccination. Indeed, these included both purely statistical methods, when a random sampling was used, and methods that might potentially lead to various biases in quantitative studies (e.g. inviting parents subscribed to antivaccination websites to take part in the study).

In a few of the studies, the main target group included those parents who followed certain alternative vaccination patterns.

It is difficult to identify one prevailing method of data collection in such studies. The quantitative approach is characterized in equal measure by telephone surveys, surveys using paper questionnaires, internet surveys, surveys conducted by mail, and surveys conducted by e-mail.

In qualitative studies, the leading role is played by semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Like other types of qualitative studies, in most cases they are characterized by small sample sizes and enrolment of participants with the help of snow-ball, targeted, purposive, or other kinds of non-probability sampling frameworks.

On the whole, the main criticism of quantitative studies of this type has to do with the fact that data collected through self-reporting, may be of dubious reliability in view of the social desirability bias phenomenon. There was only one study (Smith et al., 2011) where researchers were able to enhance the survey data with the results of objective measurements, i.e. data collected from medical records.

2. Analysis of vaccination records

In our review, this type of research played the main role in three studies (9%). All the studies examined the proliferation and correlates of vaccine refusal for children on the basis of data from health insurance companies. This method has significant advantages: the objective nature of data (especially for those countries where an overwhelming majority of medical procedures are processed by insurance companies), the possibility of a longitudinal design, and a significant volume of data. Thus, in the papers of this kind, which were included in our review, the sample size varied from 1,249 (in case of a random sampling) to 100,000-300,000 people (in case of a continuous sampling). The main limitation consists in the forced nature of the variables included in the analysis — i.e. only those that are collected by the insurance company. In a vast majority of cases, these variables include only sociodemographic data and data on seeking medical help.

3. Study of attitudes and behavior among the general population

This category only included 4 papers (13%). The main feature of these studies was the use of an experimental design, which was present in most such studies (3 out of 4), but absent from studies of any other type. In experimental studies, surveys are usually conducted using paper questionnaires or online forms, while informants are enlisted randomly or via specialized paid resources. Sample sizes are relatively small — 150–500 people. One study (Mollema et al., 2012) resembled a standard survey of parents, i.e. a questionnnaire survey of a large representative sample. A certain advantage of this particular study consisted in the presence of parallel objective measurements, including the results of blood tests, as well as data from medical records.

4. Study of health professionals’ attitudes, behavior, and experience

This category includes roughly one fifth of all papers that were analyzed (6 papers=19%). We can identify two major directions in such studies: 1) health professionals were used as experts who can define the vaccine refusal situation

(e.g. Fredrickson et al., 2004, and Quaiyum, gazi, Khan, 2010), while their own attitudes were not examined, and 2) the main focus of the study was on health professionals’ own attitudes towards vaccination. It should be noted that papers of the latter variety more often than not focused on practitioners of alternative medicine (chiropractors, naturopaths, etc.). Due to their limited numbers, a continuous sample of 300-500 people was usually used. In one particular case (Merglera et. al., 2013), researchers used the unusual design of analyzing the attitudes and behavior of health professionals (including alternative medicine practitioners) vis-a-vis the same characteristics of their patients. In all cases, these studies used quantitative cross-sectional or qualitative approaches.

5. Other Only two papers (6%) do not fit into the above classifications: one qualitative study which examined the attitudes and behavior of religious community leaders with regard to vaccination (Ruijs et. al., 2013), and another which looked at the rates and

correlates of vaccination within a specific adult subgroup — individuals suffering from chronic immunosuppressive states (Teich, Klugmann, Tiedemann, 2011).

Theoretical basis

In a vast majority of cases (22=71%), researchers did not mention the use of any theoretical model underlying their study. The most popular theoretical model in the rest of the papers was a classical health psychology theory — the health Belief Model (Rosenstock 1974) (3 papers). In addition to that, one of the studies made use of another classical health psychology theory, the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen, Fishbein 1980). Interestingly, all the studies that used the theoretical basis of the health Belief Model were organized according to a quantitative cross-sectional design.

The other studies differed totally in their theoretical bases. Qualitative studies relied upon gender theory, the “popular (lay) epidemiology” phenomenon, and probabilistic models of technical risk assessment. In quantitative experimental studies, possibilistic models of social risk assessment, as well as a mix of diverse communication theories, were used.

Measures

Our review included studies whose outcomes included both variables characterizing behavior (vaccine refusal), and those characterizing negative attitudes towards vaccination.

Vaccine refusal was operationalized in the studies in several different ways. In studies based on self-reporting, the following were used: rejection of all vaccines, or incomplete vaccination (rejection of at least one vaccine). Moreover, only in some of the studies did the authors make special mention of the fact that this refusal had to be motivated by certain personal, non-medical reasons. Thus, the group was viewed broadly, and the results of the studies might have been less representative due to the fact that those who refused for personal reasons, and those who were exempted following a doctor’s recommendation, were not distinguished.

In some cases, those who could not remember the characteristics of their vaccinations were also included in this group. however, in this instance, it is highly unlikely that in this subgroup of vaccine refusal would have been motivated by any conscious beliefs and attitudes. In some cases, a highly insignificant time period was studied (for instance, the first two years of a child’s life), and if a vaccine was not administered during this period, this case was classified as vaccine refusal (incomplete vaccination). however, in this instance, some of the cases could have been caused by a delay of vaccination, rather than vaccine refusal, and factors that influence such a decision can vary greatly. In cases where researchers relied entirely or in part on medical documents, concrete measures could also differ: a total absence of vaccines, incomplete vaccination, total number of days undervaccinated, or even being diagnosed with a vaccine-preventable disease.

Negative attitudes towards vaccination. One of methods of evaluating such attitudes consisted of a change of intention to vaccinate, which may pertain to some future situation (for instance, accepting any remaining vaccinations) or to making a decision after reading a fictional scenario. As a rule, the analysis included not only cases that demonstrated an intention to refuse vaccination, but also those with the absence of a clear intention to get vaccinated (unsure, probably).

In most other cases, attitudes were evaluated using several single local-focused items, which were grouped together in some of the cases, but were routinely analyzed on a one-by-one basis. Only one of the studies used a theoretically based index, adapted from the Ajzen and Fishbein approach (Kareklas, Muehling, Weber, 2015).

In one of the studies, it was a favorable opinion about anti-vaccination movements that served as a proxy-measure of negative attitudes to vaccination (Coniglio et al. 2011).

In studies conducted among health professionals, as well as in the paper that looked at religious leaders’ attitudes, it was a person’s intention or actual experience of advising patients not to vaccinate or to vaccinate incompletely that was used as a measure.

Discussion

The first publications based on original studies corresponding to the criteria we defined earlier, dated back to 2002 (the data was collected in 1998). Taking into consideration the fact that our analysis included studies conducted over the last 35 years (i.e. from 1980), we can conclude that active study of socio-psychological factors influencing vaccine refusal as a phenomenon (but not rejection of individual vaccines) goes back to the turn of the century and has been going for about 15 years.

Our study was able to identify several methodological peculiarities characterizing the design of vaccine refusal studies, which limit possibilities for achieving generalization and comparative analysis of their outcomes.

- The predominantly cross-sectional design does not make it clear whether cognitive factors constitute the reason, or the effect, of making a decision about vaccination.

- The “forced” nature of the factors studied, which is typical of population studies with a wide scope, as well as of studies based on analysis of medical records, which are determined by the kind of infomation that can be found in the research tools.

- Insufficient use of qualitative methods.

- Insufficient use of theoretical models during the study planning stage.

- Significant differences in formulating the dependent variable. This is typical of studies examining behavior (vaccine refusal), as well as of studies examining attitudes to vaccination.

The limitations that were identified should be taken into consideration in future studies, which will allow the collection of a pool of data that will be much less susceptible to criticism, and could be used to generalize the phenomena discovered, as well as to draw inter-territorial, temporal, and inter-group comparisons.

Conclusion

Based on the data collected, we can identify several promising lines of research that have not been thoroughly explored yet, but are capable of providing uniquely valuable information necessary to understand the nature of the vaccine refusal phenomenon:

- Longitudinal studies, aimed at analyzing the dynamic of attitudes and behavior towards vaccination among various population strata.

- Experimental and quasi-exeprimental studies of interventions aimed at changing attitudes and behavior towards vaccination. Such studies among parents, who make the decisions concerning their children's vaccination, could potentially bring the most benefits, but at the same time they present serious ethical dilemmas. That is why, perhaps, our review contained only a handful of studies using an experimental design, all of which were conducted among the general population.

- Qualitative studies or studies of the mixed methods design type, which could reveal other factors playing a role in vaccine refusal, in addition to cognitive beliefs, which the studies traditionally focus on.

- Studies of specific population groups, which could be important for understanding the psychological mechanisms of vaccine refusal and the role of social factors in that. When we began this study, we tried to find papers that would examine individuals who were completely certain of the necessity to reject vaccination, and passed on their beliefs to other people. Unfortunately, we were not able to find any studies examining members of anti-vaccine movements. We believe that one of the possible directions that future studies could take, could be the study of anti-vaccine movements' followers. Recent papers demonstrate that studies of broader groups (for instance, those that include vaccine-hesitant people as a homogeneous group), may face serious criticism, because such a group could turn out to be highly heterogeneous (e.g., Betsch 2015).

- Finally, a broadening of the studies' geography beyond North America and Western Europe, with the aim of evaluating the degree of universality or cultural specificity in the identified mechanisms that determine vaccine refusal.

Limitations

Our review has a number of limitations. First, all the studies that were included in our analysis were published in English. Second, our study focused on factors influencing the phenomenon of vaccine refusal as a whole, rather than on specific vaccines. Third, we did not attempt to find papers in databases of other publications (other than the Web of Science™ Core Collection), nor did we make any attempts to identify relevant gray literature (for example, conference proceedings). Also, certain studies may have escaped our attention because they used a different set of key terms.

Acknowledgements

This paper was prepared within the framework of research work No. NID 8.38.289.2014 “A Psychological Approach in Overcoming Negative Attitudes Among Certain Population groups towards Preventive Measures against Dangerous Infectious Diseases” (realized by the Department of Psychology, St. Petersburg State University, using federal funds allocated to St. Petersburg State University).

References

Antonova, N., Eritsyan, K., Dubrovskiy, R., & Spirina, V. (2014). Otkaz ot vaktsinatsii: kachestvennyy analiz biograficheskikh intervyu [Refusal of vaccination: qualitative analysis of biographical interviews]. Teoriya i praktika obschestvennogo razvitiya [Theory and practice of social development], 20. Retreived from http://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/otkaz-ot-vaktsinatsii-kachestvennyy-analiz-biograficheskih-intervy...

Benin, A. L., Wisler-Scher, D. J., Colson, E., Shapiro, E. D., & Holmboe, E. S. (2006). Qualitative analysis of mothers’ decision-making about vaccines for infants: the importance of trust. Pediatrics, 117(5), 1532–1541. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1728

Busse, J. W., Kulkarni, A. V., Campbell, J. B., & Injeyan, H. S. (2002). Attitudes toward vaccination: a survey of Canadian chiropractic students. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 166(12), 1531–1534.

Coniglio, M. A., Platania, M., Privitera, D., Giammanco, G., & Pignato, S. (2011). Parents’ attitudes and behaviours towards recommended vaccinations in Sicily, Italy. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 305. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-305

Connolly, T., & Reb, J. (2003). Omission bias in vaccination decisions: where’s the “omission”? Where’s the “bias?” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 91(2), 186–202. doi: 10.1016/S0749-5978(03)00057-8

Daniels, D., Jiles, R. B., Klevens, R. M., & Herrera, G. A. (2001). Undervaccinated African-American preschoolers: A case of missed opportunities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 20(4), 61–68. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00278-1

Dempsey, A. F., Schaffer, S., Singer, D., Butchart, A., Davis, M., & Freed, G. L. (2011). Alternative vaccination schedule preferences among parents of young children. Pediatrics, peds-2011. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0400

Downey, L., Tyree, P. T., Huebner, C. E., & Lafferty, W. E. (2010). Pediatric vaccination and vaccine-preventable disease acquisition: associations with care by complementary and alternative medicine providers. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14(6), 922–930. doi: 10.1007/ s10995-009-0519-5

Elukova, A. P. (2015) Prichinyi otkazov ot vaktsinatsii [Reasons for refusing vaccination]. Byulleten Severnogo gosudarstvennogo meditsinskogo universiteta: materialyi II Mezhdunarodnogo molodezhnogo meditsinskogo foruma “Meditsina buduschego – Arktike” [Bulletin of the Northern State Medical University: Proceedings of the II International Youth Medical Forum “Medicine of the Future – the Arctic”], XXXIV, 29-30.

Enriquez, R., Addington, W., Davis, F., Freels, S., Park, C. L., Hershow, R. C., & Persky, V. (2005). The relationship between vaccine refusal and self-report of atopic disease in children. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 115(4), 737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.12.1128

Falagas, M. E., & Zarkadoulia, E. (2008). Factors associated with suboptimal compliance to vaccinations in children in developed countries: a systematic review. Current Medical Research and Opinion®, 24(6), 1719–1741. doi: 10.1185/03007990802085692

Fredrickson, D. D., Davis, T. C., Arnould, C. L., Kennen, E. M., Humiston, S. G., Cross, J. T., & Bocchini, J. A. (2004). Childhood immunization refusal: provider and parent perceptions. Family Medicine, Kansas City, ANSAS, 36, 431-439.

Freed, G. L., Clark, S. J., Butchart, A. T., Singer, D. C., & Davis, M. M. (2010). Parental vaccine safety concerns in 2009. Pediatrics, 125(4), 654–659. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1962

Gaudino, J. A., & Robison, S. (2012). Risk factors associated with parents claiming personal-belief exemptions to school immunization requirements: community and other influences on more skeptical parents in Oregon, 2006.Vaccine, 30(6), 1132–1142. doi: 10.1016/j. vaccine.2011.12.006

Glanz, J. M., Newcomer, S. R., Narwaney, K. J., Hambidge, S. J., Daley, M. F., Wagner, N. M., ... & Nelson, J. C. (2013). A population-based cohort study of undervaccination in 8 managed care organizations across the United States. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(3), 274–281. doi: 10.1001/ jamapediatrics.2013.502

Gullion, J. S., Henry, L., & Gullion, G. (2008). Deciding to opt out of childhood vaccination mandates. Public Health Nursing, 25(5), 401–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00724.x

Gust, D. A., Darling, N., Kennedy, A., & Schwartz, B. (2008). Parents with doubts about vaccines: Which vaccines and reasons why. Pediatrics, 122(4), 718-725. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0538

Harmsen, I. A., Mollema, L., Ruiter, R. A., Paulussen, T. G., De Melker, H. E., & Kok, G. (2013). Why parents refuse childhood vaccination: A qualitative study using online focus groups. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1183. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1183

Jolley, D., & Douglas, K. M. (2014). The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLOS ONE, 9(2), e89177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089177

Kareklas, I., Muehling, D. D., & Weber, T. J. (2015). Reexamining health messages in the digital age: A fresh look at source credibility effects. Journal of Advertising, 44(2), 88–104. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2015.1018461

Larson, h. J., Jarrett, C., Eckersberger, E., Smith, D. M., & Paterson, P. (2014). Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine, 32(19), 2150–2159. doi: 10.1016/j. vaccine.2014.01.081

Leask, J., Kinnersley, P., Jackson, C., Cheater, F., Bedford, H., & Rowles, G. (2012). Communicating with parents about vaccination: A framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatrics, 12(1), 154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-154

Luthy, K. E., Beckstrand, R. L., Callister, L. C., & Cahoon, S. (2012). Reasons parents exempt children from receiving immunizations. The Journal of School Nursing, 28(2), 153–160. doi: 10.1177/1059840511426578

McCauley, M. M., Kennedy, A., Basket, M., & Sheedy, K. (2012). Exploring the choice to refuse or delay vaccines: a national survey of parents of 6-through 23-month-olds. Academic Pediatrics, 12(5), 375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.06.007

Mergler, M. J., Omer, S. B., Pan, W. K., Navar-Boggan, A. M., Orenstein, W., Marcuse, E. K., ... & Halsey, N. (2013). Association of vaccine-related attitudes and beliefs between parents and health care providers. Vaccine, 31(41), 4591–4595. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.039

Mollema, L., Wijers, N., Hahné, S. J., Van Der Klis, F. R., Boshuizen, H. C., & De Melker, H. E. (2012). Participation in and attitude towards the national immunization program in the Netherlands: data from population-based questionnaires. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-57

Omer, S. B., Pan, W. K., Halsey, N. A., Stokley, S., Moulton, L. H., Navar, A. M., … & Salmon, D. A. (2006). Nonmedical exemptions to school immunization requirements: secular trends and association of state policies with pertussis incidence. JAMA, 296(14), 1757–1763. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1757

Quadri-Sheriff, M., Hendrix, K. S., Downs, S. M., Sturm, L. A., Zimet, G. D., & Finnell, S. M. E. (2012). The role of herd immunity in parents’ decision to vaccinate children: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 130(3), 522–530. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0140

Quaiyum, M. A., Gazi, R., Khan, A. I., Uddin, J., Islam, M., Ahmed, F., & Saha, N. C. (2011). Programmatic aspects of dropouts in child vaccination in Bangladesh: Findings from a prospective study. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 23(2), 141–150. doi: 10.1177/1010539509342119

Reich, J. A. (2014). Neoliberal mothering and vaccine refusal, imagined gated communities and the privilege of choice. Gender & Society. doi: 10.1177/0891243214532711

Ruijs, W. L., Hautvast, J. L., Kerrar, S., Van Der Velden, K., & Hulscher, M. E. (2013). The role of religious leaders in promoting acceptance of vaccination within a minority group: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 511. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-511

Russell, M. L., Injeyan, H. S., Verhoef, M. J., & Eliasziw, M. (2004). Beliefs and behaviours: Understanding chiropractors and immunization. Vaccine, 23(3), 372–379. doi: 10.1016/j. vaccine.2004.05.027

Saada, A., Lieu, T. A., Morain, S. R., Zikmund-Fisher, B. J., & Wittenberg, E. (2015). Parents’ choices and rationales for alternative vaccination schedules, a qualitative study. Clinical Pediatrics, 54(3), 236–243. doi: 10.1177/0009922814548838

Salmon, D. A., Moulton, L. H., Omer, S. B., Patricia Dehart, M., Stokley, S., & Halsey, N. A. (2005). Factors associated with refusal of childhood vaccines among parents of school-aged children: A case-control study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159(5), 470–476. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.470

Senier, L. (2008). “It’s your most precious thing”: Worst-case thinking, trust, and parental decision making about vaccinations. Sociological Inquiry, 78(2), 207–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1475682X.2008.00235.x

Shoup, J. A., Wagner, N. M., Kraus, C. R., Narwaney, K. J., Goddard, K. S., & Glanz, J. M. (2015). Development of an interactive social media tool for parents with concerns about vaccines. Health Education & Behavior, 42(3), 302–312. doi: 10.1177/1090198114557129

Smith, P. J., Humiston, S. G., Marcuse, E. K., Zhao, Z., Dorell, C. G., Howes, C., & Hibbs, B. (2011). Parental delay or refusal of vaccine doses, childhood vaccination coverage at 24 months of age, and the health Belief Model. Public Health Reports, 126 (Suppl 2), 135. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S215

Sobo, E. J. (2015). Social cultivation of vaccine refusal and delay among waldorf (steiner) school parents. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 29(3), 381–399. doi: 10.1111/maq.12214

Teich, N., Klugmann, T., Tiedemann, A., holler, B., Mössner, J., Liebetrau, A., & Schiefke, I. (2011). Vaccination coverage in immunosuppressed patients: results of a regional health services research study. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 108(7), 105.

Wei, F., Mullooly, J. P., Goodman, M., Mccarty, M. C., Hanson, A. M., Crane, B., & Nordin, J. D. (2009). Identification and characteristics of vaccine refusers. BMC Pediatrics, 9(1), 18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-18

Wilson, K., Mills, E., Boon, H., Tomlinson, G., & Ritvo, P. (2004). A survey of attitudes towards paediatric vaccinations amongst Canadian naturopathic students. Vaccine, 22(3), 329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.08.014

Zuzak, T. J., Zuzak-Siegrist, I., Rist, L., Staubli, G., & Simoes-Wust, A. P. (2008). Attitudes towards vaccination: Users of complementary and alternative medicine versus non-users. Swiss Medical Weekly, 138(47), 713

Appendix 1.

Table 1. Methodological basis of studies

|

Source |

Object of study |

Region of study |

Year of data collection |

Study design |

Theoretical basis |

Data collection methods |

Recruitment/ Sampling |

Data analysis statistical methods |

Measures used (vaccine refusal or negative attitudes to vaccination) |

|

(Gaudino Robison, 2012). |

Parents |

USA |

2006 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Survey (by mail, by phone) |

multi-staged,

population-proportionate sampling, |

multivariate analysis |

Vaccination refusal:

exemptions to immunizations for medical, religious, or philosophical reasons

(medical records) |

|

(Mollema et al., 2012) |

General population (incl. population from regions with lower rates of vaccination and migrants) |

Nether- lands |

1995-96, 2006-7 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

1) Questionnaire

survey; |

Multi-staged |

multivariate analysis |

Vaccination refusal:

self-reported child participation in national immunization program |

|

(Smith et. al., 2011) |

Parents (with children aged 24-35 months old) |

USA |

2009 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

Health Belief Model |

Survey (by phone);

in addition to survey (by mail) of services providers; |

Sampling frame was not discussed N=11,206 |

multivariate analysis |

Vaccine refusal:

self-reported if ever refused vaccination, ever refused AND ever delayed

vaccination; |

|

(Freed et al., 2010) |

Parents (with children aged 17 years old) |

USA |

2009 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Survey (online) |

nationally representative sample |

multivariate analysis |

Vaccine refusal: Self-reported refusal of at least one

vaccine that a doctor recommended for their child(ren) |

|

(Wei et al., 2009) |

Persons for whom vaccination is recommended (children aged 0-2 years old and 6 years old) |

USA |

No data |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Analysis of records (medical and insurance companies' databases) |

Random, |

multivariate analysis |

Vaccine refusal: any type of refusal (either refusal by

parent or medical contraindication) |

|

(Glanz et al., 2013) |

Persons who are recommended vaccination (children aged 2-24 months old) |

USA |

2004-2010 |

Quantitative Retrospective matched cohort study |

No data |

Analysis of records (data from a medical/insurance company) |

Continuous sampling |

multivariate analysis |

Vaccine refusal: total number of days undervaccinated (total for all

vaccines) |

|

(Salmon et al., 2005) |

Parents (with children rejecting vaccine or completely vaccinated; primary school) |

USA |

2002-2003 |

Quantitative, Case-control

study |

No data |

Survey (by mail) |

Random within the group; N=2435 |

multivariate analysis |

Vaccine refusal: Exemption (for any reason, including medical) for 1 or more vaccine antigens required for school entry |

|

(Jolley, Douglas, 2014) |

Parents; general population |

UK USA |

2012, |

Quantitative, |

No data |

Survey

(online) |

accidental sampling (via poster

advertisements, emails and via Facebook and Twitter) |

multivariate analysis |

Negative attitudes

towards vaccination: Intention to vaccinate the child or not on a seven-point

scale after reading a fiction scenario |

|

(Coniglio et al. 2011) |

Parents |

Italy |

2008 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Questionnaire survey |

multi-staged

probability sample |

multivariate analysis |

Negative attitudes towards vaccination: Opinion about anti-vaccination movements: they should be promoted |

|

(Wilson et al., 2004) |

Health professionals (students-naturopaths) |

Canada |

1998 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Questionnaire survey |

Continuous sampling; |

multivariate analysis |

Negative attitudes towards vaccination: Intention to recommend incomplete vaccination to patients |

|

(Connolly, Reb, 2003) |

General population[2] |

USA |

No data |

Quantitative, |

Omission |

Questionnaire survey |

Accidental sampling; |

multivariate analysis |

Negative attitudes

towards vaccination: Intention to vaccinate or not the child on a seven-point

scale after reading a fiction scenario |

|

(Busse, Kulkarni, Campbell, 2002) |

Health professionals (students-chiropractors) |

Canada |

1999 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Questionnaire survey |

Continuous sampling; |

multivariate analysis |

Negative attitudes

towards vaccination: sum of 11 three-point scale items |

|

(Merglera et. Al., 2013) |

|

USA |

2002-2003 2005 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

Health Belief Model |

Survey (by mail) |

1) Random (fully-vaccinated) and

purposive - undervaccinated N=705 |

multivariate analysis |

Negative attitudes

towards vaccination: Several items. Including Low perceived benefit for child

to receive all of the recommended vaccines |

|

(Kareklas, Muehling DD., Weber T.J., 2015) |

Adults |

USA |

No data |

Quantitative, |

Original conceptual model suggested.

Attribution theory (Kelly 1967), persuasive effects of word-of-mouth,

two-step flow model of communication |

Online-survey |

2 experiments, |

multivariate analysis |

Negative attitudes

towards vaccination: index calculated (adapted from Ajzen and Fishbein 1980) |

|

(Russell et al. 2004) |

Chiropractors |

Canada |

2002 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

Theory of Reasoned Action |

Mail survey |

Continuous sample |

Multivariate analysis |

Negative attitudes towards vaccination: Encouraged/advised patients against having themselves/their children immunized |

|

(Downey, et al., 2010) |

Children |

USA |

2000-2003 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Insurance company data analysis |

Continuous sample |

Multivatiate analysis |

Vaccine refusal: Diagnosis with any of ten

vaccine-preventable diseases; had not received

any recommended vaccine during particular period |

|

(Teich, Klugmann Tiedemann, 2011) |

Persons with contra-

indications |

Ger- many |

2009 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Survey; records analysis |

Random, |

Bivariate analysis |

Vaccine refusal: Self-reported incomplete vaccination or unsure

as to whether they were adequately vaccinated or not; |

|

(Zuzak et al., 2008) |

Parents[3]

|

Switzer- land |

2006-2007 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Questionnaire survey |

Non-probability |

Bivariate analysis |

Vaccine refusal: |

|

(Shoup et al., 2015) |

Pregnant women and parents with children under 4 years old |

USA |

2010-2013 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

Health belief model |

Survey (by mail) |

1) Random (fully-vaccinated) and purposive (undervaccinated and those who delay) N=443 |

Bivariate analysis |

Vaccine refusal: |

|

(Enriquez et al., 2005) |

Parents subscribed to an anti-vaccine website |

USA |

2003 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Mail survey |

Continuous sample |

Bivariate analysis |

Vaccine refusal: refusing

all vaccines, refusing some vaccines |

|

(McCauley et al., 2012) |

Parents (with children aged 6-23 months old) |

USA |

2010 |

Quantitative, cross-sectional |

No data |

Survey (by phone) |

multi-staged probability sample |

Descriptive |

Vaccine refusal: Had

not received any vaccines |

|

(Luthy et. al., 2012) |

Parents (who rejected at least one vaccine based on personal beliefs) |

USA |

2007-2008 |

Qualitative-quantitative |

No data |

Mail survey |

Accidental (convenience) sampling; |

Descriptive |

Vaccine refusal: Refused

at least one vaccine for personal reasons |

|

(Fredrickson et al., 2004) |

Health

professionals; |

USA |

1998 |

Qualitative-quantitative |

No data |

1. Focus group (parents, health professionals – as external experts); 2. Survey (health professionals as external experts) |

1.

Accidental sampling, 32 focus groups |

Descriptive statistics |

Vaccine refusal: Refusal

for some or all vaccines |

|

(Harmsen et al., 2013) |

Parents (choosing partial vaccination or refusing vaccination) |

Nether- lands |

2011 |

Qualitative |

No data |

Focus group |

Random |

Not relevant |

Vaccine refusal: Partial

or complete vaccine refusal |

|

(Reich, 2014) |

Parents (mothers who do not have their children vaccinated or following their own schedule of vaccination) |

USA |

2007-2013 |

Qualitative |

Gender theory |

Semi-structured interviews |

Purposive |

Not relevant |

Vaccine refusal: Partial

or complete vaccine refusal |

|

(Quaiyum, Gazi, Khan, 2011) |

1. Parents (guardians) (with completely

or incompletely vaccinated children) |

Bangla- desh |

No data |

Qualitative-quantitative |

No data |

Survey; semi-structured interviews; records analysis |

1. Purposive sample: |

Not relevant |

Vaccine refusal: Not

fully vaccinated/ dropped out from vaccination |

|

(Gullion, Henry, Gullion, 2008) |

Parents (rejecting vaccine or delaying vaccination of children) |

USA |

No data |

Qualitative |

Popular (lay) epidemiology |

Semi-structured interviews |

Snow-ball and targeted sample, N=25 |

Not relevant |

Vaccine refusal: Incomplete

or delayed vaccination |

|

(Sobo, 2015) |

Parents of children who go to an alternative education school (Waldorf schools) |

USA |

No data |

Qualitative |

No data |

1) Focus group and 2) interviews |

Random sample |

Content analysis |

Vaccine refusal: Have

experience of vaccine refusal |

|

(Saada et al., 2015) |

Parents of childrn aged 12-36 months old |

USA |

2013 |

Qualitative |

No data |

Semi-structured interviews conducted by phone |

stratified

purposive sample |

Not relevant |

Vaccine refusal: |

|

(Senier l., 2008) |

Parents with a different approach to vaccination |

USA |

2004 |

Qualitative |

probabilistic models of technical risk

assessment and possibilistic |

Semi-structured interviews |

Purposive sample N=20 |

Not relevant |

Vaccine refusal:

Refusal for all vaccine; Selective vaccination |

|

(Ruijs et. al. 2013) |

Orthodox Protestant pastors |

Nether- lands |

No data |

Qualitative |

No data |

Semi-structured interviews |

Purposive sample N=12 |

Not relevant |

Negative attitudes towards vaccination: Religious leaders who preach against vaccination |

Notes.

1. Going forward, the sum total could exceed 100%, because some of the papers examined data from a number of different studies.

2. Students and non-students, who were asked to imagine they were parents

3. Adults accompanying patients of a children's hospital

To cite this article: Eritsyan K.Y., Antonova N.A., Tsvetkova L.A. (2017). Studying anti-vaccination behavior and attitudes: A systematic review of methods. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 10(1), 189-197.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.