The attitudes of Russian teenagers toward sexual aggression

Abstract

The data reported in the article describe the attitudes of teenagers to problems concerning sexual violence and aggression. Given the lack of any national systems that could monitor negative factors in the teenage environment, including sexual aggression, special value lies in the data obtained through questionnaires, as these data allow us to evaluate the prevalence of such factors, and they also describe the typical lifestyles of modern Russian teenagers.

The main objective of the study was to describe the age dynamics and gender specifics of teenagers’ attitudes toward the problem of sexual aggression: its prevalence, probable reasons for it, ways of dealing with such situations.

This article is based on data from a research project conducted in 2012 in the Krasnoyarsk region. The research particularly addressed various aspects of schoolchildrens sexual behavior and their attitudes toward sexual violence. The main research method was a paper questionnaire. It was administered to 1,540 children in the 7th, 9th, and 11th grades.

The results showed that every tenth teenager indicated the presence of sexual-violence victims in their circle. According teenagers’ opinions about the reasons for sexual violence the main reasons are “bad luck,” “provocative appearance” “carelessness”. The majority of teenagers will seek help in case of rape.

The answers of teenagers who have sexual experience regarding possible solutions for sexually traumatic situations show their readiness to take responsibility for their behavior and its consequences, as well as for their mental and physical health. In this respect sexual experience can be viewed as an indicator of teenagers’ personal and psychological readiness to lead a grownup life independently of their parents.

To sum up, analyzing schoolchildren’s replies, even to those questions that were not asked directly but in oblique form, allows us to conclude that the teenage environment involves an aggressive (unlawful) component, which usually appears to be a “hidden layer” of interpersonal relations in the microsocial circle of a schoolchild. As a result, the threat of becoming a victim of bullying (ostracism) can block a teenager’s search for help.

Received: 18.03.2015

Accepted: 10.07.2016

Themes: Social psychology; Developmental psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2015_3/psychology_2015_3_5.pdf

Pages: 61-69

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2015.0305

Keywords: puberty, prevalence of sexual aggression, reasons for sexual aggression, sup¬port for victims of sexual violence, demographic and socially stratified factors

Introduction

The data reported in the article describe the attitudes of teenagers to problems concerning sexual violence and aggression. Nowadays in Russia there is a high level of teenage crime and deviant behavior and a high rate of teenage suicides (Spravochnoe izdanie, 2009). At the same time, if information about law violations (delinquent behavior) is acknowledged by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, cases of violence and sexual aggression are often undisclosed (Argunova, 2005).

The importance of the problem of sexual aggression dining puberty is confirmed by several sociopsychological research projects. For instance, teachers’ opinions about the reasons for aggressive behavior showed a considerable increase in reasons connected to sexual background (“sexual attraction toward the opposite sex,” “feelings of jealousy toward a competitor”), specifically dining puberty, between 7th and 9th grades (Sobkin & Fomichenko, 2014).

In relation to this topic it is important to notice also the information environment of a modern teenager. In accordance with the Law for the Protection of Children from Information Able to Harm Their Health and Development (Federal Law of the Russian Federation, no. 436-FZ of 2010-12-23), a rating system was implemented. These ratings regulate the extent to which audiences of various ages may be exposed to sexual content. However, they are directed to information producers. For parents and children they function only as guidance. Moreover, they have hardly any influence on whether teenagers themselves consume these information products, be it by watching television or films or using the Internet. Because for most teenagers erotic content is highly attractive (Obrazovanie i informatsionnaya kultura, 2000; Tolerantnost v podrostkovoy subkulture, 2000), its being officially marked combined with the absence of efficient mechanisms of social control can even enhance its consumption.

Given the lack of any national systems that could monitor negative factors in the teenage environment, including sexual aggression, special value lies in the data obtained through questionnaires, as these data allow us to evaluate the prevalence of such factors, and they also describe the typical lifestyles of modern Russian teenagers.

Methods

This article is based on data from a research project conducted in 2012 in the Krasnoyarsk (Russia) region. The aim was to study teenagers’ attitudes toward various forms of deviant behavior (smoking, drinking alcohol, using drugs), as well as their orientation toward a healthy lifestyle. The research particularly addressed various aspects of schoolchildren’s sexual behavior and their attitudes toward sexual violence. The main research method was a paper questionnaire. It was administered to 1,540 children in the 7th, 9th, and 11th grades within the framework of a research program that had been started in 2002 (Sobkin, Abrosimova, Adamchuk, & Baranova, 2005a, 2005b).

Results

Analysis of the official Ministry of Internal Affairs statistics from 2004 to 2008 shows that on average more than 8,000 crimes classified as rape or as attempted rape are registered per year (Spravochnoe izdanie, 2009). Specifically, more than 10% of these crimes are committed by underage children or with their direct participation. However, the official statistics do not reflect the real situation in this area. Experts in criminal psychology note that these crimes have high latency, which causes most of them to stay unreported. There are two types of latency of a sexual crime: “artificial” and “genuine.” Artificial latency is caused by mistakes in law proceedings and low-quality police work. The official statistics are based solely on the number of suits filed in court. However, from 1997 to 2003 there was a distinct increase in suits that were rejected by the court — from 1.45 to 2.8 rejections for every four reported rapes. In other words, of four rape reports only about one results in a lawsuit. The second type of latency, genuine latency, occurs when a victim, because of such factors as fear of publicity and lack of faith in law enforcement, does not report rape or attempted rape to the police. A prosecutors’ office survey revealed that only 10-15% of victims press charges (Argunova, 2005). Thus, the actual number of such crimes surpasses the official statistics many times over. It can also be supposed that situations where underage children are involved have high genuine latency because of the age of the victims.

Considering the high prevalence of such crimes, we asked our respondents a number of questions about them. One question asked the respondents to estimate the presence of sexual-violence victims in their circle (“Is there anyone among your classmates who has ever been raped or sexually attacked?”). Every tenth teenager indicated the presence of such victims (11.0%). Among the boys the percentage who were aware of these victims was considerably higher than among the girls (14.4% and 8.2%, respectively, p < .05). Among children who had had a sexual experience, the percentage of awareness was almost three times higher than among those who had never had such an experience (19.9% and 7.3%, respectively,p<.001).

Table 1. The teenagers’ opinions about the reasons for sexual violence (%)

|

Reasons |

Average |

Boys |

Girls |

P |

|

Was just unlucky (was in the wrong place in the wrong time) |

32.8 |

33.1 |

31.9 |

- |

|

Provocative looks |

32.3 |

31.3 |

33.1 |

- |

|

Carelessness (entering an elevator with unknown people, walking alone in the street at night) |

25.5 |

20.9 |

29.2 |

.0004 |

|

Loss of self-control because of alcohol or drugs |

17.1 |

17.9 |

15.9 |

- |

|

Provocative behavior |

17.0 |

15.0 |

19.4 |

.03 |

|

Other |

1.3 |

2.2 |

0.7 |

.008 |

Special attention was given to analyzing why, from the teenagers’ standpoint, someone could become a victim of sexual violence. These situations and their causes are often the objects of psychological research (Barbaree & Marshall, 2008; Hall, 1996; Hird, 2000; Jezl, Molidor, & Wright, 1996; Koss & Oros, 1982). The main reasons given by the teenagers were “bad luck,” “provocative appearance,” “carelessness” (Table 1). The data show that the girls more often than the boys gave “carelessness” and “provocative behavior” as the reasons.

Age dynamics were most visible regarding “provocative looks.” Among the 7th grade boys, 20.5% gave this reason, while 37.0% of the 9th-grade boys did (p = .02). Among the girls, the split was 26.7% and 35.7%, respectively (p = .02). We can conclude that as children grow up their attitude toward clothing becomes more pronounced, along with their belief that appearance may cause sexual aggression. Notably, the sharp increase of such answers corresponds with the distinct physical changes of teenagers at this time. And among the girls age-based dynamics also played a role in regard to the other reasons they gave for violence. Thus, “provocative behavior” was marked in the 7th grade by 13.4% and in the 11th grade by 20.5% of the girls. “Loss of self-control because of alcohol and drugs” became the most prevalent reason given by the schoolgirls in the 9th grade (22.0%). Comparatively, among the 7thand 11th-grade girls, this reason was given by 13.4% and 11.4%, respectively. At the same time, “carelessness” as a reason declined in importance: among the 7th-grade girls it was given by 35.0%, and among 11th-grade girls, by only 25.9% (p < .05).

Special interest was directed to the difference between the answers of the teenagers who had and those who did not have sexual experience. Those who led a sexual life much more often believed that sexual aggression might be caused by “provocative looks” — 38.7%; for those who did not have sexual experience, the figure was 29.3% (p = .0002). The teenagers who did not have sexual experience more often gave “carelessness” as a reason (27.9%) than did those who led a sexual life — 18.7% (p = .0003). In other words, the teenagers who led a sexual life were more inclined than those without sexual experience to explain sexual aggression by the behavior of the victim than by circumstances or carelessness about safety.

With sexual violence, the most important topic is the provision of legal, psychological, and medical aid to the victim. The difficulties are, first, that society has no fixed attitude toward victims of sexual violence and, second, that because of serious trauma not every victim is able to apply for help. In this regard, we looked with special attention at the judgments the teenagers made about whether a victim should report violence and the reasons they gave for not doing so.

To the question “If a rape took place, should the victim report it?” 70.7% of the answers were positive. Among the girls the percentage of positive answers was higher than among the boys: 76.0% and 64.1%, respectively (p = .0001). Of the respondents, 4.2% (6.7% of the boys, 2.3% of the girls; p = .0004) thought you should tell nobody about what happened. Every fourth (25.1%) respondent found it hard to give a definite answer. Generally the data indicate that the majority of the teenagers were oriented toward asking for help in case of rape.

The reasons of those respondents who thought that you should not ask for anyone’s help were diverse (Table 2). There were clear differences between the replies of the girls and those of the boys. For the boys the most important reason was “shame and humiliation” because of the rape (26.0%, for the girls — 17.1%, p = .05). The girls were more inclined to explain that the reason was fear of publicity, “everybody will know” (33.3%, for the boys — 19.0%,p = .01). Thus, the boys accentuated personal humiliation; the girls cared more about the social rejection of the victim. Notably, age-related dynamics were visible regarding only one option: “It will cause negative reactions from people (mockery, blame, insults, etc.).” In the 7th grade this reason was given by 30.8% of the teenagers, but by the 11th grade this percentage declined to 21.3% (p = .05). In general the data shown in Table 2 indicate that fear of becoming a victim of bullying does not let adolescents seek psychological support.

Table 2. The teenagers’ reasons for why a victim of rape should not apply for help (%)

|

Reason |

Average |

Boys |

Girls |

P |

|

It will cause negative reactions from people (mockery, blame, insults, etc.) |

25.0 |

22.0 |

26.8 |

- |

|

Everybody will know it [the rape] happened |

27.2 |

19.0 |

33.3 |

.01 |

|

No one will be able to help and understand anyway |

19.4 |

13.0 |

23.6 |

.02 |

|

It is humiliating and shameful to be a victim of rape |

21.1 |

26.0 |

17.1 |

.05 |

|

It is a personal problem and you should deal with it yourself |

15.9 |

21.0 |

12.2 |

.04 |

|

Other |

4.3 |

7.0 |

1.6 |

.03 |

Finally, we asked the teenagers where to apply for help if a rape takes place (Table 3). Most of the teenagers (66.2%) thought that in case of rape the first thing you should do is tell your parents. Every fifth teenager (19.9%) believed that you should visit a medical clinic. Only 5.9% would trust this problem to a close friend. Thus, regardless of the growing importance of interpersonal intimacy, the teenagers were most inclined to discuss the subject of sexual violence with their parents. It is from parents that schoolchildren seek protection, support, and understanding in a difficult situation of personal humiliation. This finding, in our opinion, clearly illustrates the special importance of parent-child relationships during adolescence.

Table 3. The teenagers’ opinions about where to ask for help in case of sexual violence (%)

|

Where to go for help |

Average |

Boys |

Girls |

P |

|

You should let your parents know first |

66.2 |

59.3 |

71.4 |

.0001 |

|

You should visit a clinic and get checked |

19.9 |

17.2 |

21.7 |

.01 |

|

You should go to the police |

12.5 |

19.3 |

11.8 |

.0001 |

|

You should contact a professional psychologist |

8.7 |

8.9 |

11.8 |

.04 |

|

You can trust this problem only to your closest friend |

5.9 |

6.5 |

6.8 |

- |

|

You should not tell anyone and should deal with the problem yourself |

2.0 |

4.4 |

1.0 |

.0001 |

The answers also reveal gender-related dynamics: the girls more often than the boys chose to apply for help to “parents,” a “medical clinic,” or a “psychologist.” The boys were more oriented toward going to the “police,” and also they more often believed that “you should deal with the problem yourself.”

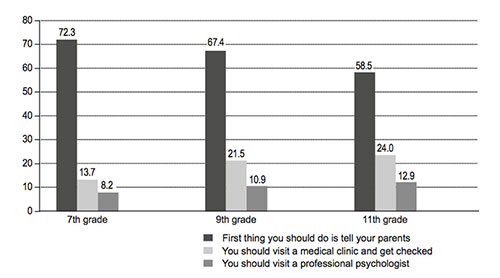

Figure 1. Age-related dynamics of the teenagers’ answers about whom they should ask for help in case of sexual violence (%)

In regard to the age-related dynamics. With increasing age the percentage of those who chose to go to their parents first declined, and at the same time there was an increase in those who chose to visit a medical clinic or a professional psychologist (Figure 1).

Thus, between the 7th and the 11th grades we can see growth in the readiness of the teenagers to independently solve problems regarding sexual violence without going to their parents. At the same time, as the children were older, there was an increase in answers related to physical and mental health (“medical clinic” and “professional psychologist”). As for those who chose to ask the “police” for help, the percentage did not change significantly. This finding proves that the level of the genuine latency of such crimes, which we mentioned previously, is equal for younger teenagers and for high school children.

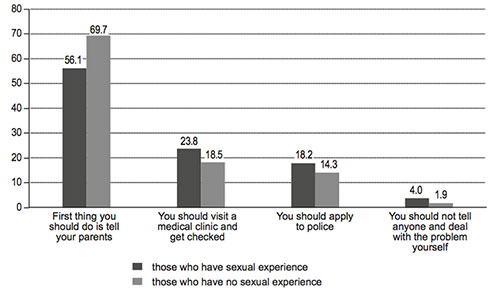

Figure 2. Teenagers’ opinions about whom they should ask for help in case of sexual violence depending on whether they have sexual experience (%)

In comparing the answers of the teenagers who did and did not have sexual experience (Figure 2), the data show that the teenagers who never had any sexual experience were more likely to ask parents for help. At the same time, teenagers who had some sexual experience stated that the victim “should deal with the problem yourself,” “visit a medical clinic,” or “apply to the police.” This information is remarkable because it shows that sexual experience, which is often considered an element in teenagers’ testing of grownup life, is connected not only with the violation of age norms but also with the achievement of a certain personal and social maturity. Essentially, the results are evidence of changes in the parent-child relationship, of an increase in independence, and of an increase in teenagers’ readiness to be responsible for their behavior and its consequences as well as for their physical and mental health. In this respect sexual experience may be viewed as an indicator of the psychological autonomy of teenagers, of their readiness to separate from parents.

Conclusion

Modern Russian teenagers encounter displays of sexual aggression not only in the media but in real life. Notably, according to our data, teenagers who have sexual experience indicate that victims of sexual violence are part of their circle three times more often that those who do not have such experience. At the same time, teenagers who lead a sexual life are more inclined than their counterparts who have not started a sexual life to explain sexual aggression as a result of the victim’s provocative looks and behavior rather than as the result of unfortunate circumstances or a disregard for safety.

The majority of teenagers will seek help in case of rape. The psychological atmosphere in a family encourages teenagers to handle the traumatic situation of a rape and to ask for help. Teenagers will appeal to parents when they are in need of support, consolation, and protection in a critical situation connected with personal humiliation.

The answers of teenagers who have sexual experience regarding possible solutions for sexually traumatic situations show their readiness to take responsibility for their behavior and its consequences, as well as for their mental and physical health. In this respect sexual experience can be viewed as an indicator of teenagers’ personal and psychological readiness to lead a grownup life independently of their parents.

To sum up, analyzing schoolchildren’s replies, even to those questions that were not asked directly but in oblique form, allows us to conclude that the teenage environment involves an aggressive (unlawful) component, which usually appears to be a “hidden layer” of interpersonal relations in the microsocial circle of a schoolchild. As a result, the threat of becoming a victim of bullying (ostracism) can block a teenager’s search for help.

References

Argunova, Yu. N. (2005). Problemy latentnosti iznasilovanii [The rape latency problems]. Nezavisimyi psikhiatricheskii zhurnal [Independent Psychiatry Journal], 1, 25-29.

Barbaree, H. E., & Marshall, W. L. (Eds.). (2008). The juvenile sex offender (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Hall, G.C.N. (1996). Theory-based assessment, treatment, and prevention of sexual aggression. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hird, M. J. (2000). An empirical study of adolescent dating aggression in the U.K. Journal of Adolescence, 23(1), 69-78. doi; 10.1006/jado.1999.0292

Jezl, D. R., Molidor, С. E., & Wright, T. L. (1996). Physical, sexual and psychological abuse in high school dating relationships: Prevalence rates and self-esteem issues. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 13(1), 69-77. doi: 10.1007/BF01876596

Koss, M. R, & Oros, C. J. (1982). Sexual experiences survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50(3), 455-457. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.50.3.455

Obrazovanie i informatsionnaya kultura [Education and information culture], (2000). Moscow: Institute of the Sociology of Education, Russian Academy of Education.

Sobkin, V. S, Abrosimova, Z. B., Adamchuk, D. V, & Baranova, E. V. (2005a). Manifestations of deviation in the adolescent subculture. Russian Education & Society, 47(7), 49-71.

Sobkin, V. S., Abrosimova, Z. B., Adamchuk, D. V., & Baranova, E. V. (2005b). Podrostok: Normy, riski, deviatsii [The teenager: norms, risks, deviations]. Moscow: Institute of the Sociology of Education, Russian Academy of Education.

Sobkin, V. S., & Fomichenko, A. S. (2014). Understanding of students’ aggressive behavior by teachers. Voprosi Psikhologii, 3, 24-36.

Spravochnoe izdanie prestupnost’ i pravonarusheniya, 2008. Statisticheskii sbornik [The reference book of crime and offences]. (2009). Moscow: Glavnyi informatsionno-analiticheskii tsentr MVD Rossii.

Tolerantnost v podrostkovoy subkulture [Tolerance in the teenage subculture], (2003). Moscow: Institute of the Sociology of Education, Russian Academy of Education.

To cite this article: Sobkin V.S., Adamchuk D.V. (2015). The attitudes of Russian teenagers toward sexual aggression. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 8(3), 61-69.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.