Moral Judgments of Modern Children and Teenagers in Russia

Abstract

The article presents a study of moral judgments shared by children and teenagers. Its results form a foundation for further enquiry into sources and conditions developing young people’s normative control system, the flexibility of this system, and the “limits” of its development defined by a particular culture. It goes on to pose questions on research methodology at the levels of either hypothetical explanatory models or the means of diagnostics. J. Piaget's investigation of children's moral judgments was prototypical for this research. The technical equipment rendered possible a more subtle analysis of the children's judgments, which, in its turn, enabled us not only to define the general tendency of development, but also to determine a number of factors of how the normative regulation of children of different ages is functioning.

Themes: Developmental psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2012/shelina.pdf

Pages: 405-421

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2012.0025

Keywords: moral judgments, regulating norms and values, collaborative skills development

Social interaction, rules and regulations for shared activities, moral development of children and its manifestations have long been the focus of attention among Russian and foreign researchers and educators, yet there still remain many open issues. The goal of this paper is to outline possible means, which would help evaluate the level of children’s collaborative skills and, consequently, enable educators to target communication skills training more precisely. Moral judgments shared by children are regarded as a manifestation of values and standards regulating their collaboration (joint efforts).

A Research Method

This research is based on a prototypical study by Jean Piaget and his colleagues (Piaget, 2006), which 1) reveals changes in child’s attitude to a rule regulating his activity in the process of mastering a specific (cooperative) type of teamwork (play); 2) exposes changes in initial norms as children introduce new rules in the process of joint activity (collective play); and 3) describes specific characteristics of these processes for different age groups. Employing the basic method of J. Piaget (suggesting children concrete situations for discussion), we established a more intricate procedure for processing their answers: all judgments expressed by the children were recorded on the tape. Hence, we could include into our analysis all versions of answering offered by the children, not only Piaget’s “definite” (non-ambiguous) judgments. We also introduced more rigid criteria for classification of the input data. Data analysis took into consideration the following: 1) whether the direct answer corresponded to a certain type of norms; and 2) whether the appendant argumentation corresponded to the direct answer. Taking all these into account, we constructed the following categorical grid for the analysis of moral judgments:

1. The so-called “first” type of norms ( See Appendix 1).

2. The “non-first” type of norms, which includes: 2.1. A “second” type of norms; 2.2. A “third” type of norms; 2.3. Particular answers named for the purposes of our study of the “other ‘non-first’ type, which includes direct corresponding answers without argumentation as well as corresponding answers with argumentation which content is not related to norms of a collective organization. 2.4. Dubious, ambivalent answers: а) dubious answers (and/or); b) comments which change in the process of reflection; c) blended answers, where the answer and its argumentation relate to different categories; d) answers of a special type: “a constructive denial ” + formal but not actual consent;

To proceed further we must clarify the terms used in description. In Piaget’s prototypical study only non-ambiguous answers were subjected to statistical analysis, and respondents’ answers were categorized through descriptive oppositions, which enabled J. Piaget to distinguish two stages in moral development: heteronomous morality and autonomous morality. This categorizing paradigm clearly demonstrates not only Piaget’s principles as a researcher but also his own cultural background. Switzerland is a country where society is traditionally seen as consolidation of autonomous subjects, and this could well be the reason why Piaget called the second stage of moral development the “autonomous morality.” In Russian culture (where systemic networks and structures tend to seek unification through submission), this term may not be appropriate. This consideration has brought us to introduce a modified implication of Piaget’s normative categories, naming heteronomous morality as the “first” normative set of standards, and autonomous morality as a “second” type of norms, with certain specifications for attribution of the latter.

Firstly, the study revealed a particular category of answers, which we named a “third” type. It covers judgments made by children and teenagers, which began with a phrasing: “Contrary to the rules, I think… I believe…”, where respondents clearly positioned themselves as a selfsufficient system. In Russian culture this construction does not form an invariable component of the “second” type of norms but, rather, stems from it; therefore, we encapsulated this type of responses into a separate category for subsequent analysis.

Secondly, among Russian teenagers rational thinking – which is one of the characteristics of Piaget’s “autonomous” morality – does not form a foundation for creation of new norms, conducive to the group’s unity and cohesion, therefore we have identified this category of answers as “other non-first” type.

3. Denial.

We have also identified “indirect” factors accompanying essential answers, including: а) active “declaration of the norms” before forming a judgment; b)“reference to conditions or circumstances as reasons for making a decision”; c) “a detailed commentary”; d) making “a statement of facts” before suggesting an extended judgment; e) indication of an active role of a child; f) “an emotional reaction” to the content of the situation.

Allocation of certain judgments to these special categories is justified by the study’s principal objective: searching for specific factors which could serve as indicators of changes in the group’s collective organization towards partnership and collaborative interaction.

New methods of collecting and processing information brought the study onto an entirely new level. In Piaget’s work analysis of interviews for each situation is presented as a separate project (the study was conducted with different groups of children). In our study every child expressed his/her judgment of seventeen situations, which enabled us not only to consider the presence/absence of certain types of norms in each age group, but also to evaluate the “stability” of each type of morality within one age group.

Thematically the situations offered during interviews fall into eight categories:

- “Cooperation and development of the notion of justice,” Situations 1–3;

- “Immanent justice,” situations 4–6;

- “Equality and authority,” Situations 7–10;

- “Issues of equality among the peers,” Situations 11–12;

- “Telling a plausible lie,” Situation 13;

- “Moral realism. Objective responsibility,” Situation 14;

- “Type of collective sanction: preventive or redemptive?”, Situa- tion 15;

- “The conflict of retributive and distributive perspectives,” Situations 16–17. (See Appendix 2 for the transcript of the situations).

Situations offered to respondents during interviews contain scenarios where adults and/or children adhere to and/or violate a specific type of moral norms.

The type of question offered for response to the situation presupposes the type of response expected: the child is invited: а) to give an evaluation; b) to express his/her own opinion, attitude; c) to give a recommendation to the adult; d) to give a prognosis of the situation’s further development; e) to identify and comment on the right, appropriate action; е) to give a “first-person” response, identifying oneself with a character in the situation; f) to give an analysis of the situation, give the reasons of the characters’ actions.

The study involved 273 respondents, aged 7 to 17; (average 12,7±2,78), 50,2% were girls, 49,8% were boys).

Analysis Results of the study confirm the validity of Piaget’s observations in the majority of cases: with age the number of appeals to the first type of moral norms decreases, and children increasingly appeal to the second type of norms. However the “first” type of norms remains dominant throughout the age span. In some situations there is a marked increase in the number of appeals to the second type of norms, while in other situations there is no such increase. In interviews about Situations 9 and 11 (see Appendix 2) there is a decrease of appeals to the second type of norms (with its initial domination at earlier stages). The results also show that development is accompanied by an overall increase in diversity of responses. Throughout the age span children simultaneously appeal to different types of moral reasoning, also giving blended answers or answers that change in the process of reflection. The study shows that manifestations of certain types of moral reasoning are connected not only with the respondent’s age (experience) but also with the specific content of a given situation and the respondent’s position, or an expected type of answer. For instance, in Situation 2, where children demonstrate “freely accepted group responsibility (2nd type of norms),” and the respondent is invited to give a recommendation to the adult, there is an increase in appeals to the first type of norms.

Analysis of the answers given by children and teenagers, revealed the following situations:

- with minimal changes within the initial level;

- with no statistically significant changes but with an overall tendency:

- of a “negative” type (the reverse of Piaget’s projections): the first type of moral reasoning increases (Sit. 1) while the second type of moral reasoning decreases (Sit. 2);

- of a “positive” type, with decreased number of appeals to the first type (Sit. 3, 9, 17) and increased number of appeals to the second type of norms (Sit. 17);

- with statistically significant changes of fragmentary (asymmetrical) nature, in only one of the two categories:

- of a “negative” type: increase of the first type of moral reasoning (Sit. 2, Sit. 13b); decrease of the second type of moral reasoning (Sit. 1 and Sit. 9);

- of a “positive” type: increased number of appeals to the second type of norms (Sit. 3);

- with statistically significant changes (decrease of appeals to the first and increase of appeals to the second type of norms) in Sit. 6, 12, 14, 15, and 16.

Thus, our study has not revealed any obvious shift in absolute dominants, described by Piaget for each of the situations.

Results drawn on the Russian sample, led us to suggest that normative moral reasoning should not be regarded as a rigid structure in the process of development, where the presence / absence of a certain type of norms (according to its prevalence) in a given age group shows only an inadequate level of its assimilation in the group. We believe that normative moral reasoning, as a whole, should be regarded as a complex system, which constantly modifies itself in accordance with specific tasks.

The study has also revealed (Sit. 13a) that in some types of activity adherence to the norms of the first and/or second type does not satisfy some of respondents’ vital needs, that is, socially significant needs at the time of great changes. More specifically, this is a need for personal and individual self-actualization (mentioned by 74% of teenagers aged 12–14 (hereafter referred to as ‘junior teens’) and 81% teenagers aged 15–17(hereafter referred to as ‘senior teens’); the need to achieve a certain status (mentioned by 17% of junior teens and 19% of senior teens); and the need for attention from significant persons (important for 40% of children aged 8 to 11).

The obtained results lead us to suggest that normative moral reasoning forms a complex unit within the overall normative control system. While at times this unit’s activity may be suspended in other periods it remains productive. The idea of a multi-level control system is not new; it was developed by P.K. Anokhin and N.A. Bernstein. The question our study sought to answer was: When, for what tasks, and under what conditions does ‘the normative unit’ come into play in regulating cooperative activity? From this perspective, we found especially interesting the study, which demonstrates that “the motivational unit” – yet another component of the overall control system – is activated only in the situation of “subjective ambiguity” (Kornilova, 2010).

The “indirect factors” identified in our study have allowed us to postulate changes not only in the structural but also in the functional role of the normative unit within the overall control system (see Table 1. Summary of “Indirect” Factors). Some “indirect factors” show up only when specific types of situations are suggested for discussion.

This statement will remain valid if we manage to demonstrate that the diversity of the study’s results is not due to the technical procedure of data processing. To ensure precision in identifying a source of the high level of ambiguity (instability) in the results, we conducted a more differ entiated analysis, dividing the aggregate sample into initial groups of respondents. Two age groups have proved to be the most revealing in this respect: junior teenagers aged 12–14 and senior teenagers aged 15–17.

Table 1

Summary of “Indirect” Factors

Sit-n № |

Declaration of Norms |

Commentary |

Statement of fact |

Circumstances as Condition of a Choice |

Indication of the Role of a Child |

Affective Evaluation |

Sit. 1 |

!!!!! |

! |

|

|

|

|

Sit. 2 |

!! |

|

|

|

|

|

Sit. 3 |

!! |

! |

|

! |

|

! |

Sit. 4 |

|

! |

|

|

|

|

Sit. 5 |

|

! |

|

|

|

|

Sit. 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sit. 7 |

|

! |

|

! |

! |

! |

Sit. 8 |

! |

! |

|

! |

! |

! |

Sit. 9 |

!! |

!! |

|

! |

! |

!! |

Sit. 10 |

!!! |

!!!! |

|

! |

! |

|

Sit. 11 |

|

!! |

|

! |

!!! |

!!!! |

Sit. 12 |

! |

! |

|

!!! |

!! |

|

Sit. 13 |

! |

! |

! |

|

|

!! |

Sit. 14 |

|

! |

|

|

! |

|

Sit. 15 |

!! |

! |

|

! |

|

|

Sit. 16 |

! |

!!! |

! |

|

|

!!! |

Sit. 17 |

!!! |

! |

|

! |

! |

|

Teenagers, aged 12–14 (junior teens), formed the following groups:

- pupils of School No. 91, which implements the Elkonin–Davydov program with a particular (dialogical) paradigm of teacher – pupil interaction;

- students of a Lyceum (in Russia: a secondary school with advanced programs in a number of disciplines) with an emphasis on research;

- children from a camp for winners of academic contests;

- children from a recreation camp (a mixed group); 5) a boarding school residents.

Teenagers, aged 15–17 (senior teens), comprised the same groups (further referred to as senior groups) with two exceptions: 1) there was no group from School No. 91; 2) there was a group of senior teens from remote villages of Mezensky district, Archangelsk region.

Analysis of individual groups within the same age span shows that statistically significant changes in teenagers’ moral judgments are observed only in certain situations (see Table 2).

Table 2a

Comparative analysis of junior teen groups (12-14 years old), including statistically significant differences in inter-group comparison for various situations

|

Sit. 3 (1st type of norms) |

Sit. 4 (1st type of norms) |

Sit.10 (2nd type of norms) |

Sit. 17 (2nd type of norms) |

Sit. 14 (2nd type of norms) |

Sit. 16 (2nd type of norms) |

|

Board. School (mах.) |

Board. School (mах.) |

Board. School (min.) |

Board. School (mах.) |

School 91 |

Camp |

School 91 |

0.004 |

0.025 |

0.025 |

0.015 |

|

|

Lyceum |

0.02 |

|

|

0.015 |

0.074 |

0.080 |

Acad. cont. winners |

|

|

|

|

0.074 |

0.034 |

Table 2b

For senior teen groups (15-17 years old)

|

Sit. 6 (1st type of norms) |

Sit. 12 (1st type of norms) |

Sit. 14 (1st type of norms) |

Sit.14 (2nd type of norms) |

Sit. 7 (2nd type of norms) |

|

Archangelsk Region (max.) |

Archangelsk Region (max.) |

Archangelsk region (max.) |

Archangelsk Region (min.) |

Boardingschool(max.) |

Acad. cont. winners |

0.004 |

0.010 |

0.000 |

|

0.093 |

Lyceum |

0.0069 |

|

0.001 |

|

0.089 |

Camp |

0.019 |

0.099 |

0.00 |

0.008 |

0.080 |

Board. school |

0.015 |

0.018 |

0.001 |

0.026 |

|

We have identified four statistically confirmed differences between the results demonstrated respectively by students from School No. 91 and residents of the boarding school, and two statistically confirmed differences between the results demonstrated by the junior teens respectively from the boarding school and the Lyceum. We have also revealed statistically significant differences in discussing one situation between pupils of School No. 91 and Lyceum students, and between pupils of School No. 91 and academic contest winners (junior teens). In one situation there were differences between the results of Campers on the one hand, and Lyceum students and academic contest winners on the other, with a distinct tendency among the latter to choose the merit-based line of reasoning.

Thus, while analyzing the content of moral judgments formed by teenagers, we observe that in the development of normative control structures “the environment” is only instrumental to some degree, in certain situations. A close look at overall trends and tendencies, comparative analysis within the 12–14 age group demonstrates a certain acceptable response dispersion within clear parameters, with three groups setting these parameters (the group of boarding school residents on the one hand and the groups of pupils from School N. 91 and the Lyceum on the other). The study shows that, in some sense, these groups form polar opposites: for many situations boarding school residents demonstrated maximum results of appealing to the first type of norms, while School 91 and Lyceum students showed minimal appeal to the first type of norms. At the same time, for some situations School 91 and Lyceum students demonstrated maximum results of appealing to the second type of norms.

Comparative analysis for groups of senior teens (ages 15–17) reveals a tendency for unification of results in all the groups from Moscow region. We observed only one statistically significant difference related to the second type of norms. Statistically significant differences were evident in comparing the results of some groups from Moscow region with the results of the group from remote villages in Archangelsk region, but only for some situations.

Thus results of the study demonstrate certain peculiarities of individual groups (which are especially important to consider when developing targeted programs for training in collaborative skills). At the same time they show the common “profile” of normative control system development among Russian teenagers (with negligible exceptions).

Despite a certain flexibility of the normative control system, evident within the entire age span under the study, and variability of the normative unit itself, there still remains a potential for establishing a prevailing normative dominant in each age group. Results of the study lead us to state that for the majority of the situations Russian children, both junior and senior teenagers, tend to choose the first type of moral reasoning, while the development of the second (cooperative) type of norms does not even reach the level demonstrated by 12-years-old Swiss teenagers from Piaget’s study.

The content analysis of situations offered for discussion has shown that:

- Russian respondents (children as well as junior and senior teens) perceive adults as people who (in interactions with children) are prone to function primarily as superiors in relation to subordinates, but not as equal partners. It must be added that in some cases (School No. 91, Lyceum) the actual nature of interaction along the lines of Adult – (Child + Child) and Child – Adult produces an increase in appeals to the second (cooperative) type of normative moral reasoning. Even these groups, however, show no radical restructuring in the normative moral reasoning as a whole. It is possible that the developmental paradigm of the normative sphere is limited by foundational characteristics of our community culture. One question that remains open here is just how fatal the situation is.

- The position of an adult is associated with the necessity of redemptive punishment, which propels children toward a behavioral strategy, based on avoiding punishment (lying; indirect denial + formal consent). In situations when a respondent is compelled to identify his/her judgement with the position of an adult (in order to give a recommendation), the increase in appealing to the second type of norms is minimal. If the situation is presented clearly, that is, a transgression and a culprit come clear and definite, and a punishment must follow, the first type of norms dominates. If a situation is less clear-cut (if a culprit is not suggested by the context), there is an increase in appealing to the second type of norms.

- In situations based on the Adult – Child plotline we have observed no increase in appealing to the second type of norms.

- In complex scenarios involving both Adult – Child and Adult – (Child + Child) plotlines, we have observed an increase in appealing to the second type of norms. Interestingly, if a scenario gives grounds for appealing to the second type of norms along the Child – Child plotline (allowing an indulgence, helping a sick brother) in Sit. 9, the indices are higher than in the situations where one of the children violates the equality principle (Sit. 8) or breaches it out of carelessness (Sit. 17).

- The maximum increase in appealing to the second (cooperative) type of norms is observed in discussion of situations where children interact without adults present (Sit. 12, 15).

- The situation where the plotline involves a group of children violating the norms of the second type (Sit. 11), requires an entirely different set of norms, for the purposes of the study called the norms of a “third” type, based on working out of a personal attitude, personal choice, and individual responsibility for the choice rather than on consolidation of a group.

Discussion

Our attempt to achieve the objective pursued has led not so much to clear answers as to new questions. The results of this research project can be analyzed from several different perspectives.

The search for diagnostic means has highlighted an urgent need for a basic explanation of what we observe. We are dealing with a flexible, constantly changing and complex system which, in its turn, forms part of a wider control system. Specific characteristics of these tiered systems depend on the nature of interfunctional connections. This is an entirely different approach to the material, and the only conclusion that can be made at this point is that a mere statement of fact doesn’t give us any meaningful answers.

On the other hand, we have certain factual knowledge, which demonstrates (on the horizontal level) development and operation of normative moral controls. This produces a new set of questions: Would the identified normative “profile” be characteristic only for Russia at the time of great changes? What exactly lies behind the study results?

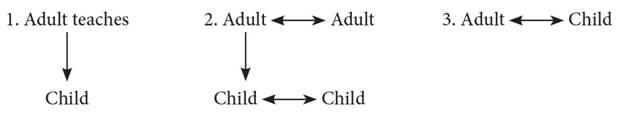

We believe that one of the ways to approach the study results is to look at the basic forms of how our respondents actually interact along the lines of Adult – Child, Adult – (Child + Child) and Child – Child schemes. We have sufficient reasons for accepting Piaget’s thesis that children’s moral judgments reflect the practices of interaction in which they are engaged. For these we employ М. Mead’s paradigm (Mead, 1988) with three basic schemes for Adult – Child interaction:

Results of the study suggest that in actual interaction practice Russian children fairly often encounter Scheme 1, with one explication: according to the study by V.V. Abramenkova (Abramenkova, 2008), Interaction Scheme 1 has always coexisted with children’s subcommunity. It was this interaction scenario, and not the Adult – Child scheme, that was applied to settle most issues in archaic communities. Scheme 2 stems from Scheme 1. We believe that to improve communicative competencies of modern youths by using the current technologies for training skills (actions with given parameters) we should, first of all, specify the positional background and provide (create and propose) necessary models and examples. Results of this study demonstrate the absence (minimal presence) of partner relationships as a prototype model in the Adult – Adult scheme, as well as minimal conditions for implementing the scheme Child + Child without Adult Dictatorship.

References

- Abramenkova, V.V. (2008). Sotsial’naya psihologia detstva [Social psychology of childhood]. Moscow: Per Se.

- Kornilova, Т.V., Chumakova, М.А., Kornilov, S.А., Novikova, М.А. (2010). Psihologia neopredelyonnosti: yedinstvo intellektual’no-lichnostnogo potentziala [The Psychology of ambiguity: a unity of intellectual and personal potential]. Мoscow: Smysl.

- Mead, М. (1988). Kultura i mir detstva [Culture and the world of childhood]. Мoscow: Progress.

- Piaget, J. (2006). Moral’noye suzhdeniye u rebyonka [The moral judgment of a child]. Мoscow: Academichesky Proyekt.

Appendix 1

Table

Basic Characteristics |

The First Type of Norms |

The Second Type of Norms |

| 1. What are the rules based on? | Respect for the adult and for the rule per se. |

From “respect for the rule” to mutual respect of everyone involved and ability to change the rules. |

| 2. Source | Ready-made. Given by adults |

Younger children receive them from older children. Older children change existing rules and make new rules of cooperative activity |

| 3. Status of rules and norms | Unchangeable. Given for all times. Accepted by everyone. |

Change with time. |

| 4. The highest (moral) achievement | Declaration of equality, equal rights for everyone |

The highest moral achievement is equality of opportunity to exercise equal rights |

| 5. End point | Heteronomy + moral realism |

Independence |

| 6. Primary mechanism | Social compulsion, imposition of opinions and customs |

Cooperation inspires ways of intellectual and moral exchange: the spirit of the game is more important than restrictions imposed by the rules |

| 7.Attitude to an individual. Consideration of needs and abilities | Individual traits are not taken into consideration. General norms for everyone. |

The rules change: from formal adherence to considerations of needs and abilities. |

|

MANIFESTATIONS |

|

| 8. Types of justice | Based on retributive responsibility |

Based on freely assumed responsibility |

| 9. Ways of maintaining justice | Expiatory sanctions |

1. Reciprocity sanctions 2.Preventive sanctions |

| 10.Responsibility | Communicable and objective |

From objective to freely assumed. |

| 11. Attitude to authority | Authority is absolute |

Understanding that authority destroys reciprocity |

Appendix 2

Situations offered to respondents for discussion (Piaget J., 2006)

Unit I. Collective and Communicable Responsibility (Ch. 3. Cooperation and the Idea of Justice , p. 296)

Story 1. A mother forbade her three sons playing on her computer (which she used for work at home). As soon as she left, one of the sons said, “How about playing anyway?” A second son agreed, but a third said: “No. Mom told us not to. I am not touching her computer.” When the mother returned home, she found out that the kids had used her computer, and punished all three of them. Is it fair?.. Why or why not?

Story 2. After classes several boys started playing snowballs near their school, and one of them threw his snowball at the window of the next house and broke the glass. The children saw it all. A man came out of the house and asked who had done it. Since no one responded he then complained to the teacher. The next day the teacher asked the whole class who had broken the neighbor’s window, but again no one confessed. The boy who’d broken the window said it wasn’t him, and the others didn’t want to betray him. What should the teacher do? Why?

Story 3. A boy’s father invited friends of his son to visit the family country house over the winter break. The children were throwing snowballs at the garage wall. They were permitted to do so on one condition: not to break the window of the apartment over the garage. One of the boys was more awkward than the others and couldn’t throw snowballs as well as the rest of them. At one point he took a pebble, packed it in snow (like a pie with a stone stuffing) and hurled it. The snowball flew beautifully high… and smashed right into the window. The children were too engrossed in the game and didn’t notice whose snowball it was... When the father came back he grew angry and asked who had broken the window. The boy who had done it said it wasn’t him. Everyone else said the same, because they didn’t know who had done it. What should the father do: punish everyone or punish none of the boys?.. Why?

Unit II. Immanent Justice (p. 318)

Story 4. Once two boys were stealing apples in the garden. Suddenly the groundskeeper showed up, and the boys ran to escape. The groundskeeper caught one of them. As the other boy was going back home he took the long way. He had to cross the river over an old, half-broken bridge. He tread thebridge and fell into the water. What do you think about it? If he hadn’t been stealing apples but decided to walk home over that bridge anyway, do you think he would have fallen into the water?.. Why or why not?

Story 5. In physics lab the teacher would not let the students touch the instruments. Once as the teacher was writing something on the blackboard, one “scapegrace” started twisting something in one of the instruments… and caught his finger in it very badly. If the teacher had allowed the children to touch the instruments, do you think this student would have caught his finger? Why or why not?

Story 6. A young man (boy) would show no obedience to his parents. Once he took their laptop computer, which was strictly forbidden. He’d returned the laptop to its place, though, before they got home, so no one suspected anything. The next day when he was outside he caught his favorite jacket on a nail and tore it. Why do you think it happened? Do you think it would have happened if he had been obedient?

Unit II. Equality and Authority (p. 346)

Story 7. At summer camp everyone must do his or her turn in duties (wait at tables, clean up rooms, stand a duty at the main gate, etc.) Once someone who was supposed to be on gate duty left the gate unattended. The camp director was walking by and saw it. A young man was running by. He had already done all his chores and now was hurrying to meet his girlfriend at the camp dance. The camp director asked the young man to take another turn on gate duty. What should this young man do?... Why?

Story 8. A mother was very tired and asked her children to help her clean the house and cook the dinner. The girl was supposed to peel potatoes and the boy was asked to vacuum the carpets. One of the children, though, went outside to play instead. Then the mother told the child who stayed home to do the other chore as well. What did she/he tell their mother? Why? What do you think of this action?

Story 9. There were three brothers in a family: an elder boy and two younger twins. Every morning each of the children polished one’s own boots (such was the rule in the family). One day the elder brother got sick, and the mother asked one of the twins to polish the elder brother’s boots along with his own. What do you think of this?.. Why?

Story 10. A man had two sons. One of them would always get grumpy when he was asked to do the shopping. The other son, though he no less disliked shopping, would always go acquiescently. The father would ask the placable son to go shopping more often. What do you think of this? Why?

Unit IV. Issues of Equality among the Peers (p. 386-386).

Story 11. Children were playing catch outside (on their school sportsground…). When the ball got kicked into the street, a boy (he was just passing by) kicked it back and stopped to watch the game. Before long the children who were playing would ask him to run and get the ball each time it got kicked into the street. What do you think of this? How often does something like this happen? Can it be that children “use” someone? What kind of person usually finds himself ‘in the shoes’?

Story 12. Children were picnicking on the grass. Everyone laid his sandwich down next to himself. Suddenly a dog stole up to the child who was sitting last and snatched away his sandwich. What can be done?... How often do children share now?

Unit V. A Likely (Plausible) Lie (p. 203).

Stories 13а and 13b are read together. Younger children are asked to retell the stories. Everyone is asked: “Why did these children say what they said?”

Story 13.

А. A young man (boy) couldn’t draw very well but really wanted to learn. Once he saw a nice drawing done by someone else he said, “I drew this.”

B. Once a young man was at home playing with his mom’s watch (when she was out) and misplaced it. When his mother came home and started looking for her watch, he said he hadn’t seen it.

Unit VI. Moral Realism. Objective Responsibility (p. 170)

Story 14.

We read the two stories and ask one question: Is everyone here equally to blame? Or do you think one person is more to blame than the other? Why?

Story 14a: A young man was in his room. He was asked to come to dinner several times but was too engaged in what he was doing and “didn’t hear” the summons. His mother (grandmother) got tired of waiting for him and decided to clean up the kitchen (putting a tray of cups on a stool). Then the young man finally decided to get some food, walked into the kitchen, threw the door open, and smashed the whole tray onto the floor, breaking fifteen cups.

Story 14b: Once, when his mother was out, a boy (young man) decided to get some jam from the cupboard. The mother told him not to eat this particular jam because it was very special (dogberry or walnut), quite hard to get or make, and a favorite of his ailing grandmother. The jam jar was on one of the top shelves, and as the boy was trying to get it, he accidentally pushed a cup, which fell and broke.

Unit VII. Preventive Sanction and Expiatory Sanction (p. 38).

Story 15. Younger schoolchildren asked senior pupils to show them something in the school museum (physics lab). The seniors agreed on the condition that the juniors would be very careful with the exhibit (object) they wanted to see. However, in the process the younger pupils started arguing, pushing and shoving, and eventually the exhibit (object) fell and got broken, or was damaged. When the senior students saw this they said they would never give anything to the juniors again. Did they do the right thing by saying this? Why or why not?

Unit VIII. Conflict between Retributive and Distributive Perspectives

Story 16 (p. 331) A woman had two daughters. One daughter was obedient and the other is naughty. The mother loved the obedient daughter more and saved the best treats for her. What do you think of this?

Story 17 (p. 337) A woman was boating on the lake with her three sons. The weather was beautiful, and everything was fine. She gave each of the boys a candy bar. One of the boys started fidgeting and, in the end, dropped his candy bar into the water. What should they do? The mother has no more treats… Should they give this boy nothing, or should everyone give him a piece of his candy bar? Why?

To cite this article: Shelina S.L., Mitina O.V. (2012). Moral Judgments of Modern Children and Teenagers in Russia. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 5, 405-421

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.