Intercultural relations in Kabardino-Balkaria: Does integration always lead to subjective well-being?

Abstract

This article examines intercultural relations in Kabardino-Balkaria. Among a great number of ethnic groups living in Kabardino-Balkaria, Kabardians and Balkars are one of the largest (they are so-called titular ethnic groups). Russians are the second largest of the ethnic groups after Kabardians. We report here the results of an empirical study of the intercultural relations, mutual acculturation, and adaptation of Kabardians and Balkars (N = 285) and Russians (N = 249). Specifically, we examine the relevance of three hypotheses formulated to understand intercultural relations: the multiculturalism hypothesis, the integration hypothesis, and the contact hypothesis. We conducted path analysis in AMOS with two samples: a sample of Russians and a sample of the two main ethnic groups (Kabardians and Balkars), and we further compared the path models with each other. The results revealed significant effects of security, intercultural contacts, multicultural ideology, acculturation strategies, and acculturation expectations on attitudes, life satisfaction, and self-esteem in both samples. These findings partially confirm the three hypotheses in both groups. However, we also identified a regionally specific pattern. We found that, in the Russian sample, the integration strategy was negatively related to wellbeing, while contact with the dominant ethnic group was positively related to well-being. At the same time, in the sample of Kabardians and Balkars, acculturation expectations of integration and assimilation were positively related to well-being. In the article, we discuss these regional specifics.

Received: 14.11.2015

Accepted: 20.12.2015

Themes: Multiculturalism and intercultural relations: Comparative analysis; Psychology of ethno-cultural issues

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2016_1/psychology_2016_1_4.pdf

Pages: 57-73

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2016.0104

Keywords: acculturation strategies, acculturation expectations, intercultural contact, intercultural relations, multicultural ideology, life satisfaction, perceived security, perceived discrimination, perceived threat, ethnic tolerance

In our study, we sought to verify three hypotheses of intercultural relations (the multiculturalism hypothesis, the integration hypothesis, and the contact hypothesis). Although these hypotheses have received support in many intercultural contexts, it is important to evaluate them in different ways in different countries and regions. In Russia, which is a multicultural society with many ethnonational republics, each republic has its own particular features of intercultural relations. Thus, the hypotheses can be confirmed only with acknowledgment of certain specific regional characteristics. In this study, we focused on the specific way each of these hypotheses works in the context of intercultural relations in the Kabardino-Balkar Republic (KBR). Kabardino-Balkaria can be viewed as a new context in which to examine these issues. Russians, who are the former Soviet political elite in the Republic, are now in a minority position. In contrast, there has been a growth of ethnic consciousness among the Kabardians and the Balkars, who are the titular population. To begin, we briefly describe the history and specific features of intercultural relations between Russians and the titular ethnic groups in the KBR.

The context of the intercultural relations of Russians and the titular ethnic groups in the Kabardino-Balkar Republic

Kabardino-Balkaria was formed in 1922 as an autonomous oblast by merging the Kabardian autonomous region and the Balkar region of the Mountain Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The Russian population of these regions was involved in this process too. Since then, in Kabardino-Balkaria the principle of parity has been accepted by each side. The principle of parity means equal representation of Kabardians, Russians, and Balkars in the government structures of the Republic (Akkiyeva, 1999).

Nowadays the Kabardino-Balkar Republic (KBR) is a part of the North Caucasian Federal District of the Russian Federation. The Russian population is the second largest after the Kabardians. Although both Russians and Balkars have an essential impact on the Republic, Kabardians are the most influential. It is important to note that Kabardians and Balkars are Sunni Muslims and the Russians are Orthodox Christians.

Russians have been living in the KBR for several generations. However, the outflow of the Russian population from the region has been increasing. From 1989 to 2010 the Russian population in the KBR decreased from 31.9% to 22.5% (Vsesoyuznaya …, 2015; Itogi … 2010, 2012). A survey conducted in 2007 among Russians in Kabardino-Balkaria (N = 520) revealed that every fourth Russian would like to leave the Republic. More than one-third (37%) of the people aged 18–24 years intended to leave (Akkiyeva, 2013). Dzadziev (1999) claims that the main reasons for the Russian population outflow were socioeconomic and ethnopolitical factors. The replacement of qualified Russian specialists by specialists from the titular ethnic groups of the North Caucasus republics was the most important socioeconomic factor. In the period before and after II World War, Russians were brought to the Republic to set up the industry sector, and qualified workers among the titular ethnic groups were trained at this time. As a result, qualified workers from these groups displaced Russian workers. At the same time, an increase in interethnic tension between the titular ethnic groups and the Russian population, caused by the process of “sovereignization[1](Dzadziev, 1999), was the most important ethnopolitical factor. During the sovereignization of the republics of the North Caucasus, the Russian population acquired the status of an “ethnic minority” with decreased representation in government structures and prestigious employment areas (i.e., the principle of parity was not respected) and with decreased prospects for social growth (Dzadziev, 1999).

In this way, the process of sovereignization became a source of the growth of ethnic identity among the titular ethnic groups in the North Caucasus. In ethnosociological research in the KBR by Kobakhidze (2005), the majority of respondents had positive ethnic identity. In addition, the results revealed a pronounced tendency toward hyperidentity (excessively expressed ethnic identity) in the Kabardians — and a tendency toward hypoidentity (weakly expressed ethnic identity) in the Russians. Kobakhidze explains the tendency toward hyperidentity in the titular ethnic groups as a result of “retraditionalization”. Retraditionalization, which was supported by the North Caucasus ethnic groups after the collapse of the Soviet Union, is the revival of traditional mechanisms of social self-regulation and universal principles of self-organization and the increasing significance of social relationships based on traditional etiquette rules.

This tendency toward traditionalism is a factor in ethnic cultural maintenance and leads to strengthening of the ethnic component in the structure of group social identity. Kobakhidze (2005) notes that it is likely that other ethnic groups that are communicating with those of the North Caucasus on a daily basis react to the increasing significance of the titular groups’ ethnic identity by opposite changes in the structure of their own identities. We agree that these opposite tendencies in the transformation processes of ethnic-group identities influence interethnic attitudes. Previous research (Lepshokova, 2012) with Russians and Balkars living in Kabardino-Balkaria and Moscow has shown that Russians in Kabardino-Balkaria and Russians in Moscow (where they are the majority ethnic group) have strongly pronounced and positive civiс identity, which is stronger than their ethnic identity, probably because Russian ethnic and civiс identities are the same to a certain extent. The level of positivity of civiс identity of Russians in the KBR is significantly higher than the level of positivity of civiс identity of the Russian population in Moscow and of Balkars living in the KBR. This finding indicates that mechanisms of social-psychological defense are activated in Russians as an ethnic minority in the KBR through the high level of civic, but not ethnic, identity.

Thus, the KBR is a unique region in regard to intercultural relations. This region was historically formed as a multicultural region consisting of three dominant groups: Kabardians, the largest “titular” group; Russians, an ethnic minority within the KBR; and Balkars, the third largest group in the Republic belonging to the titular group, too. Thus, from our point of view, this region is a unique field for social and psychological studies of interethnic interactions and for testing intercultural relations hypotheses.

Regarding the acculturation strategies of the Russians in Kabardino-Balkaria, the strategy of integration is the most preferred, followed by the strategies of marginalization, separation, and assimilation (Lepshokova, 2012).

The research hypotheses

In a multicultural society, day-to-day intercultural encounters are inevitable and are of vital importance (Hui, Chen, Leung, & Berry, 2015). In order to understand intercultural relations in the KBR, we tested three hypotheses of intercultural relations: multiculturalism, integration, and contact (Berry, 2013a).

Multiculturalism as a psychological concept is an attitude related to the political ideology regarding acceptance of the culturally heterogeneous composition of the population of a society (Berry & Kalin, 1995). Existing studies show that the level of support for multiculturalism varies in different countries. A positive attitude toward multiculturalism has been found in Canada (Berry & Kalin, 1995) and New Zealand (Sibley & Ward, 2013). Neutral attitudes have been found in the Netherlands (Breugelmans & Van de Vijver, 2004), the United States (Citrin, Sears, Muste, & Wong, 2001), and Australia (Ho, 1990). A slightly negative attitude has been found in the United Kingdom and Spain (Van de Vijver, Breugelmans, & Schalk-Soekar, 2008).

Based on the Canadian data, Berry, Kalin, and Taylor (1977) proposed the multiculturalism hypothesis, “the belief that confidence in one’s identity will lead to sharing, respect for others and to the reduction of discriminatory attitudes” (Berry, 2006, p. 724). Multiculturalism exists in those countries in which the ethnic majority does not feel the threat that may come if minorities seek to preserve their own cultures (Richardson, op den Buijs, & Van der Zee, 2011; Tip et al., 2012) and allows (or helps) minorities to preserve their original cultures (Liu, 2007).

Historically, Russia has always been a multicultural society; over 180 ethnic groups have lived together here for several centuries. Although most Russian republics are characterized by the presence of an ethnic majority, in fact almost every republic is ethnically heterogeneous. Each individual republic has a unique system of intercultural relations, and the Kabardino-Balkar Republic is no exception. The basic notion of the multiculturalism hypothesis is that only when people are secure in their identities will they be in a position to accept those who differ from them; conversely, when people feel threatened, they will develop prejudice and engage in discrimination (Berry, 2013a). The multiculturalism hypothesis is confirmed in many studies (Berry & Kalin, 2000; Ward & Masgoret, 2008).

According to the contact hypothesis, intercultural contact will contribute to mutual acceptance in certain conditions, especially when there is equality of rights (Allport, 1954). Pettigrew and Tropp (2006) performed a meta-analysis of a variety of research from different countries. The results they obtained generally support the contact hypothesis: intergroup contact is usually negatively related to pronounced prejudices, in both the dominant and the nondominant groups. In addition, cross-ethnic friendships are related to psychological well-being (Bagci, Rutland, Kumashiro, Smith, & Blumberg, 2014; Hui et al., 2015; Mendoza-Denton & Page-Gould, 2008).

Berry (2011) has proposed that the choice of an integration strategy is related to a greater number of ethnic minorities or migrants becoming successfully adapted. With an integration strategy ethnic minorities will try to join in the life of the new society and will become a part of it without losing ties to their ethnic group. For the ethnic majority, the choice of an integration strategy assumes psychological acceptance of the culture of ethnic minorities. If the ethnic majority allows minorities to preserve their cultural heritage and includes them in social life, we can assert that the ethnic majority is the one choosing the integration strategy. If minorities have ties with members of their own group and the host population, they are better adapted and have a higher subjective well-being (Berry, 2013a). A meta-analysis of studies devoted to the evaluation of the influence of integration on psychological adaptation allows us to confirm the positive relationship between these constructs (Nguyen & Benet-Martinez, 2013). The hypothesis of the impact of integration on adaptation and subjective well-being is called the integration hypothesis (Berry, 2013a). However, in some studies the importance of the strategy of assimilation in the adaptation of ethnic minorities is demonstrated also (Jasinskaja-Lahti, Horenczyk, & Kinunen, 2011; Kus-Harbord & Ward, 2015; Ward, 2013).

On the basis of the aforementioned conceptualizations and the description of the social context of the KBR, we formulated the following hypotheses:

- 1. The multiculturalism

hypothesis: the higher one’s sense of security, the higher one’s willingness to

accept those who are culturally different. Specifically:

1a. The higher the perceived security and the lower the perceived discrimination among the ethnic minority (the Russians), the higher the support of multicultural ideology and ethnic tolerance.

1b. The higher the perceived security and the lower the perceived threat among the titular ethnic groups (the Kabardians and the Balkars), the higher the support of multicultural ideology and ethnic tolerance. - 2. The contact

hypothesis: intercultural contact promotes mutual acceptance (under certain

conditions, especially that of equality). Specifically:

2a. The higher the intensity of friendly contacts of the ethnic minority-group members (the Russians) with the members of the titular ethnic groups (the Kabardians and the Balkars), the higher the Russians’ level of ethnic tolerance, the higher their preference for the integration and assimilation strategies, and the higher their life satisfaction and self-esteem.

2b. The higher the intensity of friendly contacts of the members of the titular ethnic groups (the Kabardians and the Balkars) with the minority group members (the Russians), the higher the titular groups’ level of ethnic tolerance, the higher their preference for integration and assimilation, and the higher their life satisfaction and self-esteem. - 3. The integration

hypothesis: those who prefer the integration strategy have higher psychological

and sociocultural adaptation. Specifically:

3a. The higher the preference for the acculturation strategy of integration among the ethnic minority (the Russians), the higher their level of life satisfaction, self-esteem, and sociocultural adaptation.

3b. The higher the preference for integration and assimilation among members of the titular ethnic groups (the acculturation expectations of the Kabardians and Balkars), the higher their level of life satisfaction and self-esteem.

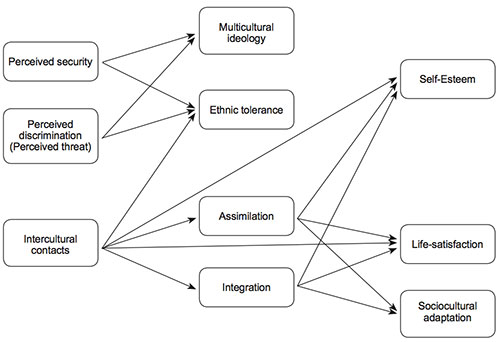

The proposed model for the study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Proposed model. Sociocultural adaptation and perceived discrimination were used in the group of Russians only; perceived threat was used in the group of Kabardians and Balkars only.

Method

Research aim

Our goal was to test and evaluate the relevance of the three hypotheses of intercultural relations in Kabardino-Balkaria.

Research design and procedure

We used a “snowball” sampling strategy, asking our friends, acquaintances, and colleagues who live in Kabardino-Balkaria to distribute a questionnaire among Russians, Kabardians, and Balkars. Participation in the study was voluntary. The Russians completed the questionnaire for the ethnic minority with acculturation strategies. The Kabardians and the Balkars completed the questionnaire for the ethnic majority with acculturation expectations. The questionnaire took approximately 30 minutes to complete.

Sample

The sample consisted of 534 respondents: 249 were Russians who had been living in Kabardino-Balkaria for more than 20 years, and 285 were Kabardians and Balkars, as representatives of the titular ethnic groups of the Republic (162 Kabardians and 123 Balkars). Social-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

|

Groups |

N |

Age |

Gender |

||

|

|

|

M |

SD |

Male |

Female |

|

Ethnic minority (Russians) |

249 |

42.4 |

21.2 |

82 |

167 |

|

Titular ethnic groups (Kabardians and Balkars) |

285 |

44.1 |

22.4 |

89 |

196 |

|

Total |

534 |

43.3 |

21.8 |

171 |

363 |

Table 1. Social-demographic characteristics of the sample

Measures

The study used the Mutual Intercultural Relations in Plural Societies questionnaire ( Berry, 2013b); the scales were translated into Russian and adapted for use in Russia (Lebedeva, 2009; Lebedeva & Tatarko, 2013). For this research, we used the following responses on a 5-point scale: 1 — totally disagree; 2 — disagree; 3 — not sure/neutral; 4 — agree; 5 — totally agree.

Perceived security. The overall perceived-security score was calculated as an average of three items from three domains of security (cultural, economic, and personal). Cultural security was measured by one item, such as “There is room for a variety of languages and cultures in this Republic”; economic security was measured by one item, such as “This Republic is prosperous and wealthy enough for everyone to feel secure”; personal security was measured by one item, such as “A person’s chances of living a safe, untroubled life are better today than ever before”. Cronbach’s alpha was .59 for the Russian sample and .49 for the Kabardian and Balkar sample.

Intercultural contacts. Intercultural contacts were measured by parallel questions for the Russians and for the members of the titular ethnic population. We asked respondents about the number of their close friends and their frequency of contact with them. The Russians were asked about friends among the Kabardians and the Balkars, and the Kabardians and the Balkars were asked about their friends among the Russians. This combination of number and frequency of intercultural contacts is termed the intensity of contacts. We asked only about close friendly contacts because friendly contacts implicitly involve equality, one of the conditions stipulated in the contact hypothesis. Cronbach’s alpha was .87 for the Russian sample and .82 for the Kabardian and Balkar sample.

Multicultural ideology. This construct assessed support for multiculturalism as a public policy and practice. It was measured by four items, such as “We should recognize that cultural diversity is a fundamental characteristic of Kabardino-Balkaria”, “A society that has a variety of ethnic and cultural groups is more able to tackle new problems as they occur”. These items were used both for the Russians and for the Kabardians and the Balkars. Cronbach’s alpha was .77 for the Russian sample and .65 for the Kabardian and Balkar sample.

Ethnic tolerance. This construct was measured by three items, such as “We should promote equality among all groups, regardless of ethnic origin.” This scale was used with both samples. Cronbach’s alpha was .78 for the Russian sample and .73 for the Kabardian and Balkar sample.

Perceived discrimination. Perceived discrimination was measured by three items, such as “I have been discriminated against at work (promotion, benefits) / during my studies because of my ethnicity”. This scale was used with the Russians only; Cronbach’s alpha was .91.

Perceived threat. Perceived threat was measured by three items, such as “I feel people of other ethnicities have something against me”. This scale was used with the Kabardians and the Balkars only; Cronbach’s alpha was .91.

Acculturation strategies of the Russians. For the purposes of this research, we used only the acculturation attitudes of integration and assimilation, which are the two strategies that indicate a willingness to engage with the larger society. The integration scale includes four items, such as “I feel that Russians should maintain our own cultural traditions but also adopt those of the titular population of the Republic”; Cronbach’s alpha was .78. The assimilation scale included four items, such as “I prefer social activities which involve Russians only”. Cronbach’s alpha was .88. These scales were used with Russians only.

Acculturation expectations of the titular ethnic group. Paralleling the strategies scale used with the Russians, the scales measuring the acculturation expectations of integration and assimilation were used with the Kabardians and the Balkars. The integration expectation was measured using three items, such as “I feel that Russians should maintain their own cultural traditions but also adopt those of the Kabardians/Balkars”. Cronbach’s alpha was .62. The assimilation expectation was measured using four items, such as “I feel that Russians should adopt Kabardian/ Balkar cultural traditions and not maintain their own”); Cronbach’s alpha was .90. These items were used with the Kabardians and the Balkars only.

Sociocultural adaptation. This scale assessed competence in daily intercultural living among migrants/ethnic minorities (Wilson, 2013). The Russians indicated how much difficulty they experienced while living in Kabardino-Balkaria in each of five areas of daily life, such as interpersonal communication and community involvement. Items were recoded positively. Cronbach’s alpha was .86.

Life satisfaction. This scale included four items, such as “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”, “So far I have got the important things I want in life”; it was used with both samples. Cronbach’s alpha was .91 for the Russian sample and .85 for the Kabardian and Balkar sample.

Self-esteem. This scale included four items, such as “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself,” “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”; it was used with both samples. Cronbach’s alpha was .85 for the Russian sample and .87 for the Kabardian and Balkar sample.

Demographic variables. In addition to these psychological constructs to measure the observed variables, questions about respondents’ backgrounds, such as gender, age, and level of education, were included. We used these questions with both samples

Data processing

We used path analysis with AMOS version 19 (Arbuckle, 2010). Independent models were constructed for each sample and were compared with each other.

Results

Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for the measures and the results of the t-test for the two samples.

|

Variables |

M (R/KB)a |

SD (R/KB) |

t |

Cohen’s d |

|

Perceived security |

3.33/3.53 |

.84/.88 |

2.59** |

.23 |

|

Intercultural contacts |

3.24/2.89 |

1.12/1.21 |

3.42*** |

.30 |

|

Perceived discriminationb |

2.04 |

1.08 |

– |

– |

|

Perceived threatc |

2.19 |

1.10 |

– |

– |

|

Multicultural ideology |

3.80/3.94 |

.83/.72 |

-2.11* |

.18 |

|

Ethnic tolerance |

4.08/3.99 |

.89/.94 |

1.17 |

.10 |

|

Assimilation |

1.90/2.30 |

.91/1.14 |

-4.40*** |

.38 |

|

Integration |

3.65/3.64 |

.78/.62 |

1.69 |

.01 |

|

Self-esteem |

4.17/4.20 |

.63/.66 |

-.49 |

.05 |

|

Life satisfaction |

3.54/3.86 |

1.02/.78 |

-4.10*** |

.35 |

|

Sociocultural adaptationd |

3.39 |

.95 |

– |

– |

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and results of the t-test for the samples of Russians (N =249) and Kabardians and Balkars (N =285) Russians/Kabardians and Balkars; b, d used in the group of Russians only; c used in the group of Kabardians and Balkars only. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

We found significant differences in perceived security, intercultural contacts, multicultural ideology, assimilation, and life satisfaction of the two groups. Perceived security, multicultural ideology, assimilation, and life satisfaction were significantly higher in the sample of Kabardians and Balkars than in the sample of Russians. We also found that intercultural contacts was significantly higher in the sample of Russians than in the sample of Kabardians and Balkars. Cohen’s d coefficients were relatively low; they indicate that the differences between the two groups on these variables might depend on the sample sizes.

In order to obtain an overall assessment, we examined the three hypotheses of intercultural relations (multiculturalism, contact, and integration) together by combining them into one model for each sample. This approach allowed us to examine the similarities and the differences in the structure of relationships across samples.

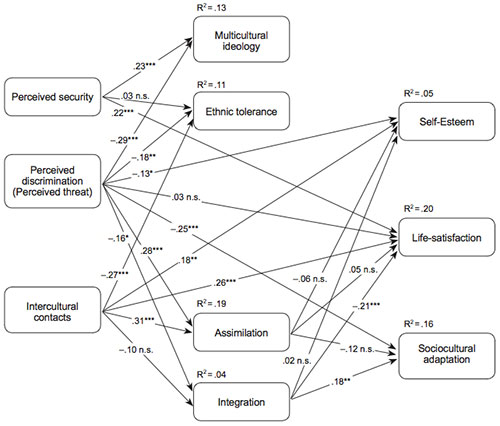

Results for the Russian sample are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Standardized regression weights and significance levels of the path model (Russians). *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, n.s. — not significant. χ² =31.38; df =13; p = .003; χ²/df =2.41; CFI=.96; RMSEA =.07; SRMR =.04.

The multiculturalism hypothesis for the Russian sample (1a) was partially supported: perceived security was a significant positive predictor of multicultural ideology (β = .23, p < .001), but it was not a predictor of ethnic tolerance (β = .03, n.s.). Perceived discrimination was a significant negative predictor of ethnic tolerance (β = -.18, p < .01) and of multicultural ideology (β = -.29, p < .001).

In addition perceived security directly influenced life satisfaction (β = .22, p < .001). Also, perceived discrimination was a significant negative predictor of the integration strategy, (β = -.16, p < .05), self-esteem (β=-.13, p < .05), and sociocultural adaptation (β = -.25, p < .001); it was a significant positive predictor of an assimilation (β = .28, p < .001) strategy.

The contact hypothesis for the Russian sample (2a) was partially supported: the Russians’ friendly contacts with the Kabardians and the Balkars significantly and positively predicted the assimilation strategy (β = .31, p < .001), life satisfaction (β = .26, p < .001), and self-esteem (β = .18, p < .01). However, intercultural contacts negatively predicted ethnic tolerance (β = -.27, p < .001).

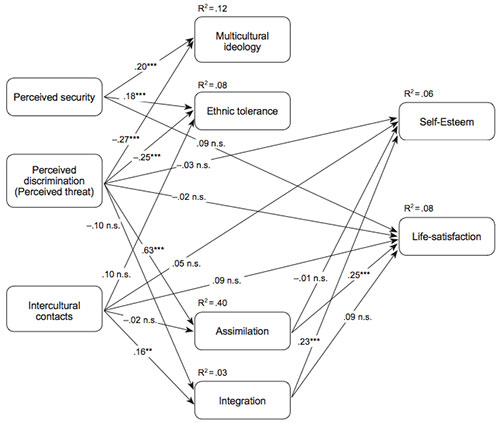

Figure 3. Standardized regression weights and significance levels of the path model (Kabardians and Balkars). **p < .01, ***p < .001, n.s. — not significant. χ² = 19.48; df =8; p = .013; χ²/df =2.44; CFI=.97; RMSEA =.07; SRMR =.03.

The integration hypothesis for the Russian sample (3a) was partially supported. The integration strategy was a significant positive predictor of sociocultural adaptation (β = .18, p < .01) and a significant negative predictor of life satisfaction (β = .–21, p < .001), but it was not a predictor of self-esteem (β = .02, n.s.). We did not find a significant impact of the assimilation strategy on the sociocultural adaptation, life satisfaction, or self-esteem of the Russians.

Results for the Kabardian and Balkar sample are shown in Figure 3.

Consistent with the multiculturalism hypothesis for the sample of Kabardians and Balkars (1b), the levels of support for multicultural ideology and ethnic tolerance were positively predicted by their perceived security (β = .20, p < .001 and β = .18, p < .01, respectively). Perceived threat was a significant negative predictor of ethnic tolerance (β = –.25, p < .001) and multicultural ideology (β = –.27, p < .001). Thus, the multiculturalism hypothesis was fully supported in the sample of Kabardians and Balkars. In addition, we found that perceived threat was a positive predictor of the acculturation expectation of assimilation (β = .63, p < .001).

The contact hypothesis for the sample of Kabardians and Balkars (2b) was partially supported. Intercultural contacts positively predicted the integration strategy (β = .16, p < .01), but it did not predict ethnic tolerance (β=.10, n.s.), the assimilation strategy (β = -.02, n.s.), life satisfaction (β = .09, n.s.), or self-esteem (β = .05, n.s.).

The integration hypothesis for the sample of Kabardians and Balkars (3b) was partially supported. The integration acculturation expectation was a positive predictor of self-esteem (β = .23, p < .001) but not of life satisfaction (β = .09, n.s.). We also found that the assimilation acculturation expectation was a positive predictor of life satisfaction (β = .25, p < .001) but not of self-esteem (β = –.01, n.s.).

Discussion

How have the above-mentioned hypotheses been confirmed and in light of which specific regional factors? The multiculturalism hypothesis was supported in the sample of Kabardians and Balkars (the titular ethnic groups) and was partially supported in the Russian sample (the ethnic minority). Perceived security predicted multicultural ideology in both samples, but it predicted tolerance only in the sample of Kabardians and Balkars. Also, perceived threat was a negative predictor of multicultural ideology and ethnic tolerance among the Kabardians and the Balkars, whereas perceived discrimination was a negative predictor of multicultural ideology and ethnic tolerance among the Russians. These results are in line with Berry’s conceptualization (Berry, 2013a).

In addition, we found that perceived threat in the Kabardians and Balkars predicted the acculturation expectation of assimilation. This phenomenon has been found in previous studies (Callens, Meuleman, & Valentová, 2013) and can be explained by the group-threat theory (Bobo, 1999), which states that when a minority group challenges the societal position of the majority group by, for example, maintaining its own culture, the majority group will feel threatened and prefer assimilation (Davies, Steele, & Markus, 2008; Tip et al., 2012).

Perceived discrimination was also negatively related to the integration strategy and the sociocultural adaptation of the Russians. These findings are similar to those of research showing that young immigrants were most likely to be categorized in the integration profile when little discrimination was perceived (Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006).

Special attention should be paid to the positive relationship between the perceived discrimination of the Russians and a strategy of assimilation. Researchers argue that if people feel rejected by others in the larger society, they reciprocate this rejection by choosing a strategy that avoids contact with others outside their own group (Berry, 2013a). However, some studies indicate that minority members can react to discrimination by following an individual path to social mobility and can thereby dissociate themselves from the low status/devalued in-group (Wright, Taylor, & Moghaddam, 1990). This strategy depends on the intergroup structure and presupposes that the group boundaries are seen as relatively permeable. If this is the case, then membership in the higher status group (the titular group) can be achieved (Verkuyten & Reijerse, 2008). In early research, this phenomenon was called “passing” (Berry, 1970).

Intercultural contacts were significantly and positively related to the assimilation strategy but were negatively related to ethnic tolerance. In addition, intercultural contact of Russians with the titular ethnic groups had a significant and positive effect on their self-esteem and life satisfaction. We suppose that the absence of equal status of the titular ethnic groups and the Russian minority in the KBR is one of the reasons why the contact hypothesis was partially confirmed with Russians: equality is one of the main prerequisites of the contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954).

The contact hypothesis also was partially confirmed with the titular ethnic groups: the frequency of their intercultural contacts with Russians was positively related to the acculturation expectation of integration among the Kabardians and the Balkars but had no relationship to their ethnic tolerance.

The integration hypothesis was partially confirmed for both groups in the KBR: the preference of the Russians for the integration strategy had a positive connection with their sociocultural adaptation and a negative relationship with their life satisfaction. The positive relationship between the integration strategy and sociocultural adaptation has been confirmed in numerous studies (Nguyen & Benet-Martínez, 2013; Sam & Berry, 2006). The negative relationship between the integration strategy and the life satisfaction of the Russians is consistent with data obtained by Kus-Harbord and Ward (2015) in a study of ethnic Russians in Estonia. This study revealed that interaction between the acculturation dimensions of maintenance and participation demonstrated that participation in Estonian culture was associated with lower life satisfaction under the conditions of high cultural maintenance. As we mentioned before, Russians were the former Soviet political elite in the KBR, but now they occupy a minority position in the ethnic hierarchy, as they do in other ethnonational republics of Russia. But the life satisfaction of the Russians in our study was predicted directly by their relationships (intercultural contacts and perceived security) with the host population in the KBR.

The preference of the Kabardians and the Balkars for integration was related positively and significantly to their self-esteem, but it was not related to their life satisfaction. An assimilation expectation had the opposite effect: it was not related to self-esteem but was positively related to life satisfaction.

In other words, within the ethnic majority, the integration hypothesis transformed into the assimilation hypothesis. However, both integration and assimilation contributed to the well-being (life satisfaction and self-esteem) of the titular ethnic groups in the KBR.

Conclusion

We can conclude that the three research hypotheses were partially confirmed. The multiculturalism hypothesis was partially confirmed in the sample of Russians (ethnic minority) and fully confirmed with the Kabardians and the Balkars (the titular ethnic groups). But we also found an additional positive relationship between perceived discrimination (for the Russians) or threat (for the Kabardians and the Balkars) and the assimilation strategy/expectation.

The contact hypothesis was partially confirmed for the host population in the KBR and for the Russian ethnic minority. Moreover, the frequency of Russians’ contacts with the titular ethnic groups was negatively related to ethnic tolerance, a relationship that stands in opposition to the contact hypothesis. Yet frequency of contact was positively related to the acculturation strategy of assimilation, a finding that corresponds to the contact hypothesis.

The integration hypothesis was partially confirmed in both samples in the KBR. For Russians, the integration strategy led to sociocultural adaptation but reduced their life satisfaction. The titular ethnic group’s acculturation expectation of integration predicted their higher self-esteem, and their acculturation expectation of assimilation predicted their life satisfaction.

The intercultural relationships described by these three hypotheses were derived from Canadian multicultural policy and can have regional specifics in other countries, as proved by the sample of this region of Russia. They are partially confirmed yet still possess a number of specific features that cannot be ignored.

Limitations

We considered Kabardians and Balkars as one majority group in the Republic. However, they may differ in the way they perceive Russians and in the way Russians perceive them. Thus, it would be interesting to split Kabardians and Balkars into two separate subsamples and to test the hypotheses on three samples to receive more precise results.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 15-18-00029).

References

Akkiyeva, S. I. (1999). Sostoyaniye i perspektivy razvitiya mezhetnicheskikh otnosheniy v Kabardino-Balkarskoy Respublike [The state and prospects for the development of interethnic relations in the Kabardino-Balkar Republic]. Tsentral’naya Aziya i Kavkaz [Central Asia and the Caucasus], 2(17). Retrieved from http://www.ca-c.org/journal/cac-02-1999/st_17_akkieva.shtml

Akkiyeva, S. I. (2013). Russkie v Kabardino-Balkarii: migratsionnyie ustanovki i etnokulturnyie potrebnosti [Russians in Kabardino-Balkaria: migration tenets and ethno-cultural needs]. «Belyie pyatna» rossiyskoy i mirovoy istorii [“White Spots” of the Russian and World History], 5–6, 9–20. Retrieved from http://www.publishing-vak.ru/file/archive-history-20135/1-akkieva.pdf

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2013). A review of articles on multiculturalism in 35 years of IJIR. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37(6), 676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.09.006

Arbuckle, J. L. (2010). IBM SPSS Amos 19 user’s guide. Crawfordville, FL: Amos Development Corporation.

Bagci, S. C., Rutland, A., Kumashiro, M., Smith, P. K., & Blumberg, H. (2014). Are minority status children’s cross-ethnic friendships beneficial in a multiethnic context? British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 32, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/bjdp.12028

Berry, J. W. (1970). Marginality, stress and ethnic identification in an acculturated Aboriginal community. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 239–252. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100303

Berry, J. W. (2006). Mutual attitudes among immigrants and ethnocultural groups in Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(6), 719–734. doi: 10.1016/j. ijintrel.2006.06.004

Berry, J. W. (2011). Immigrant acculturation: Psychological and social adaptations. In A. Assaad (Ed.), Identity and political participation (pp. 279–295). London: Wiley.

Berry, J. W. (2013a). Intercultural relations in plural societies: Research derived from multiculturalism policy. Acta de Investigación Psicológica, 3(2), 1122–1135. doi: 10.1016/S20074719(13)70956-6

Berry, J. W. (2013b). Mutual Intercultural Relations in Plural Societies (MIRIPS). Retrieved from http://www.victoria.ac.nz/cacr/research/mirips

Berry, J. W., & Kalin, R. (1995). Multicultural and ethnic attitudes in Canada: An overview of the 1991 national survey. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 27, 301–320. doi: 10.1037/0008-400X.27.3.301

Berry, J. W., & Kalin, R. (2000). Multicultural policy and social psychology: The Canadian experience. In S. A. Renshon & J. Duckitt (Eds.), Political psychology: Cultural and cross-cultural foundations (pp. 263–284). New York: Macmillan.

Berry, J. W., Kalin, R., & Taylor, D. (1977). Multiculturalism and ethnic attitudes in Canada. Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 55(3), 303–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x

Bobo, L. D. (1999). Prejudice as group position: Microfoundations of a sociological approach to racism and race relations. Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 445–472. doi: 10.1111/00224537.00127

Breugelmans, S. M., & Van de Vijver, F.J.R. (2004). Antecedents and components of majority attitudes toward multiculturalism in the Netherlands. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53(3), 400–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00177.x

Callens, M.-S., Meuleman, B., & Valentová, M. (2013). Perceived threat, contact and attitudes towards the integration of immigrants. Evidence from Luxembourg. Working paper. Retrieved from preprint https://lirias.kuleuven.be/handle/123456789/411158

Citrin J., Sears, D. O., Muste, C., & Wong, C. (2001). Multiculturalism in American public opinion. British Journal of Political Science, 31, 247–275. doi: 10.1017/s0007123401000102

Davies, P. G., Steele, C. M., & Markus, H. R. (2008). A nation challenged: The impact of foreign threat on America’s tolerance for diversity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(2), 308–318. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.308

Dzadziev, A. B. (1999). Russkoye naseleniye respublik Severnogo Kavkaza: Puti mira na Severnom Kavkaze [The Russian population of the republics of the North Caucasus: The way of peace in the North Caucasus]. Collective monograph of the Institute of Ethnography and Anthropology, Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved from http://www.valerytishkov.ru/cntnt/ publikacii3/kollektivn/puti_mira_.html

Ho, R. (1990). Multiculturalism in Australia: A survey of attitudes. Human Relations, 43, 259– 272. doi: 10.1177/001872679004300304

Hui, B.P.H., Chen, S. X., Leung, C. M., & Berry, J. W. (2015). Facilitating adaptation and intercultural contact: The role of integration and multicultural ideology in dominant and non-dominant groups. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 45, 70–84. doi: 10.1016/j. ijintrel.2015.01.002

Itogi vserossiyskoy perepisi naseleniya 2010 (2012). [The results of the National Population Census of 2010]).] Vol. 11: Svodnyye itogi Vserossiyskoy perepisi naseleniya 2010 [Summary results of the national census in 2010]. Retrieved from http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/ perepis2010/croc/vol11pdf-m.html

Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Horenczyk, G., & Kinunen, T. (2011). Time and context in the relationship between acculturation attitudes and adaptation among Russian-speaking immigrants in Finland and Israel. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(9), 1423–1440. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2011.623617

Kobakhidze, E. I. (2005). Integratsionnyye i dezintegratsionnyye protsessy v mezhetnicheskom vzaimodeystvii na Severnom Kavkaze (na primere RSO-A i KBR) [Integration and disintegration processes in interethnic relations in the North Caucasus (the example of RNO-A and KBR)]. SOCIS, 2, 66–74.

Kus-Harbord, L., & Ward, C. (2015). Ethnic Russians in post-Soviet Estonia: Perceived devaluation, acculturation, well-being, and ethnic attitudes. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 4(1), 66–81. doi: 10.1037/ipp0000025

Lebedeva, N. M. (2009). Teoreticheskiye podkhody k issledovaniyu vzaimnykh ustanovok i strategiy mezhkul’turnogo vzaimodeystviya migrantov i naseleniya Rossii [Theoretical approaches to the study of the mutual attitudes and strategies of intercultural interaction among migrants and the population of Russia]. In N. M. Lebedeva & A. N. Tatarko (Eds.), Strategii mezhkul’turnogo vzaimodeystviya migrantov i naseleniya Rossii: Sbornik nauchnykh statey [Strategies for the intercultural interaction of migrants and the population of Russia: A collection of scientific articles] (pp. 10 –63). Moscow: RUDN.

Lebedeva, N. M, & Tatarko, A. N. (2013). Immigration and intercultural interaction strategies in post-Soviet Russia. In E. Tartakovsky (Ed.), Immigration: Policies, challenges and impact (pp. 179–194). New York: Nova Science.

Lepshokova, Z. H. (2012). Strategii adaptacii migrantov i ih psihologicheskoe blagopoluchie (na primere Moskvy i Severnogo Kavkaza) [Adaptation strategies of migrants and their psychological well-being (the case of Moscow and the North Caucasus)]. Moscow: Grifon.

Liu, S. (2007). Living with others: Mapping the routes to acculturation in a multicultural society. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31, 761–778. doi: 10.1016/j. ijintrel.2007.08.003

Mendoza-Denton, R., & Page-Gould, E. (2008). Can cross-group friendships influence minority students’ well-being at historically White universities? Psychological Science, 19, 933–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02179.x

Nguyen, A.-M.T.D., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2013). Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(1), 122–159. doi: 10.1177/0022022111435097

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Richardson R., op den Buijs, T., & Van der Zee, K. (2011). Changes in multicultural, Muslim and acculturation attitudes in the Netherlands armed forces. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 580–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.04.004

Sam, D. L., & Berry, J. W. (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of acculturation psychology. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511489891

Sibley, C. G., & Ward, C. (2013). Measuring the preconditions for a successful multicultural society: A barometer test of New Zealand. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37(6), 700–713. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.09.008

Tip, L. K., Zagefka, H., González, R., Brown, R., Cinnirella, M., & Na, X. (2012). Is support of multiculturalism threatened by . . . threat itself? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(1), 22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.09.011

Van de Vijver, F.J.R., Breugelmans, S. M., & Schalk-Soekar, S.R.G. (2008). Multiculturalism: Construct validity and stability. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32, 93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.11.001

Verkuyten, M., & Reijerse, A. (2008). Intergroup structure and identity management among ethnic minority and majority groups: The interactive effects of perceived stability, legitimacy, and permeability. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 106–127. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.395

Vsesoyuznaya perepis’ naseleniya 1939 goda, 1959 goda, 1970 goda, 1979 goda, 1989 goda. Natsional’nyy sostav naseleniya po regionam Rossii (2015). [All Union Population Census of 1939, 1959, 1970, 1979, 1989. National composition of the population in the Russian regions]. Demosсope Weekly, nos. 651–652. Retrieved from http://www.demoscope.ru/ weekly/ssp/rus_nac_70.php?reg=50

Ward, C. (2013) Probing identity, integration and adaptation: Big questions, little answers. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37, 391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.04.001

Ward, С., & Masgoret, A-M. (2008). Attitudes toward immigrants, immigration, and multiculturalism in New Zealand: A social psychological analysis. International Migration Review, 42(1), 227–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00119.x

Wilson, J. (2013). Exploring the past, present and future of cultural competency research: The revision and expansion of the sociocultural adaptation construct (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand.

Wright, S. C., Taylor, D. M., & Moghaddam, F. M. (1990). Responding to membership in a disadvantaged group: From acceptance to collective protest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 994–1003. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.994

Notes.

1.Sovereignization is defined as the aspiration to achieve independence and the process for doing so.

To cite this article: Lepshokova Z. Kh., Tatarko A. N. (2016). Intercultural relations in Kabardino-Balkaria: Does integration always lead to subjective well-being? Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 9(1), 57-73.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.