Value shifts in Vietnamese students studying in Russia

Abstract

Background. The extension of intercultural contacts in the present-day world calls for a thorough study of what effect these contacts produce on the human personality. When an individual is suddenly immersed in a different culture, his or her consciousness becomes a battlefield where new values conflict with the old. The person experiences an axiological shock, a ``value clash,” which urges him or her to undertake a re-examination of his/ her value system as a whole.

Objective. The objective of this study was to determine the changes occurring in the value system of Vietnamese students obtaining their higher education in Russia.

Design. A longitudinal study was performed involving 100 Vietnamese students in Russian universities. The measurement methods used in the study were: 1) the modified M. Rokeach Value Survey (Rokeach, 1973; Kudrjashov, 1992), in which the original set of values was expanded by 20 additional values typical of the Vietnamese people; and 2) the technique for assessing acculturation strategies developed by J.W. Berry (Strategii mezhkul’turnogo vzaimodejstvija..., 2009).

Results. In the course of a year of residence in Russia, specific changes (or “shifts”) occurred in the value systems of the Vietnamese students which proved to be statistically significant. Among the goal values (the same as terminal values, in the terms of M. Rokeach) which took on more weight were Productive Life and Materially Prosperous Life, while among instrumental values, Tidiness and Frugality became more prominent. A difference between the value dynamics in male and female students was also established, with the value pattern of male students proving to be more dynamic. The next finding was the difference in value dynamics between students coming from urban and rural settlements. There was one more quite unexpected finding: The value pattern changed more noticeably in respondents with an acculturation profile of “Integration and Separation,” than in those with profiles of “Integration and Assimilation” and “Pure Integration.”

Conclusion. Therefore we see that factors such as gender, type of environment (rural/urban) the individual comes from, and the strategy of acculturation used by the individual, act as mediators exerting their own influence upon the dynamics of his/her value patterns.

Abbreviation: PF = Preliminary Faculty

Received: 30.09.2017

Accepted: 22.01.2018

Themes: Luria’s Legacy in Cultural-Historical Psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2018_2/psych_2_2018-2_maslova.pdf

Pages: 14-24

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2018.0202

Keywords: acculturation, value pattern, value dynamics, Vietnamese students, acculturation strategies, acculturation profile.

Introduction

The extension of intercultural contacts in the present-day world calls for an emphasis upon a thorough study of what effect these contacts produce on the human personality. Values constitute the core of every culture. Through the process of enculturation, they become the major component of personality, and serve as its compass, its navigator, and determinant of the individual's stance toward the world. The value pattern is a rather stable component of personality. It is a construction which helps the personality take a certain position toward the whole outside world with all its challenges (Leontiev, 1993). At the same time, the personal value system is rather changeable, since it is a derivative of the ever-changing environment, on one hand, and of the actual level of personal development, on the other (Yanickyi, 2012).

When an individual finds himor herself immersed in a remote culture, which is very different from his own–so strange and alien to him, full of unfamiliar norms, rules, and concepts, and above all, very largely based on another set of values–he or she is plunged into a state of value chaos and confusion. In making the horrifying discovery that the familiar values (both common and personal), which he or she "absorbed with one's mother's milk," are now coming into a clash with the completely different values of the residential population, and that his or her explanatory models do not work here at all, the person may undergo an axiological crisis, or axiological shock. In the individual mind, the two sets of values, the new ones and the old, clash — a very painful condition, often producing panic or depression. To overcome such a crisis, one needs to indulge in a total re-examination of his or her value system as a whole. This extremely tense and difficult task may become the first step to establishing a set of modified personal values for the individual.

How will the values change? What factors affect the process of value changing in the course of the acculturation process? The phenomenon of value shifts in a changing social environment has been studied well enough in connection to dramatic changes in socio-economic and political life (e.g. Zhuravleva, 2013; Lebedeva & Tatarko, 2007; Le, 1998), but the problem has not been studied very much in the context of acculturation. The study of value dynamics in young people coming to our country from a culture very distant, in every respect, from our own, seems to us to be a great model for research in this field. These young people provide a vivid example of how values may change under the cross-cultural interaction and radical immersion into another culture, particularly in light of the fact that university students are notable for their great sensitivity to social influences, and that the problem of personal values is very acute at this age.

Methods

The empirical study we carried out, in collaboration with Duk T. Bui, was aimed at detecting changes in the value system of Vietnamese students during their study in Russia.

The more specific aims were as follows:

-

Detect changes in the value system of Vietnamese students during their early period of study in Russia.

-

Make a comparison between the value dynamics in Vietnamese male and female students.

-

Compare the value dynamics in Vietnamese students coming from urban and rural settlements.

-

Compare the value dynamics in Vietnamese students with different strategies of acculturation.

Sample: 100 Vietnamese students in Moscow colleges and universities, who had a mean age of 21 at the beginning of the study. 54 subjects were female and 46 male; 52 came from urban and 48 from rural settlements.

A longitudinal method was applied in the study. Two measurements were taken of each student precisely at a one year interval. The first measurement was taken when the subjects were attending preliminary courses (Preliminary Faculty or PF), designed mainly for foreign students to study the Russian language, at which time their living experience in Russia had been four months on average. The second measurement was taken exactly a year later, when they were students of the first course, and had experienced living in Russia for 1 year and 4 months.

The main measuring instrument applied in this study was the modified M. Rokeach Value Survey (Rokeach, 1973; Kudrjashov, 1992). For the purposes of this study, we extended Rokeach's value list by adding 20 more values peculiar to the Vietnamese people, which had been identified in a number of studies by Vietnamese scholars (Le, 1998; Ho, 2010; Phạm, 2012). We added 15 "traditional" and five "conditionally contemporary" Vietnamese values, seven of which belonged to the category of "terminal" or goal values (Homeland, Peace, Humanity, Justice, Equality, and Following Traditions), and 13 of which belonged to the category of "instrumental" values (Industry; Modesty; Self-Esteem; Respect for the Elderly; Simplicity; Construction of Relations Based on Personal Emotional Bias; Gratitude; Frugality; Fidelity; Contemplativeness; Collectivity; Spirit of Community, Solidarity, Mutual Love and Interconnection, and Ideals of the Revolution). To assess acculturation strategies, we used the technique developed by J. W. Berry (Strategii mezhkul'turnogo vzaimodejstvija..., 2009), which aimed to identify four strategies of acculturation, known as Assimilation, Separation, Integration, and Marginalization. We also used various mathematical statistical methods (Wilcoxon T-criterion, binomial criterion, and a method of cluster analysis) for statistical data verification.

Results

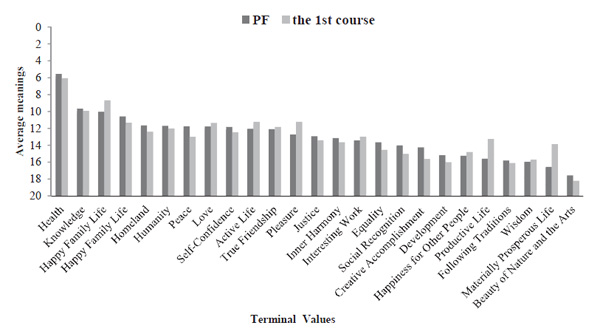

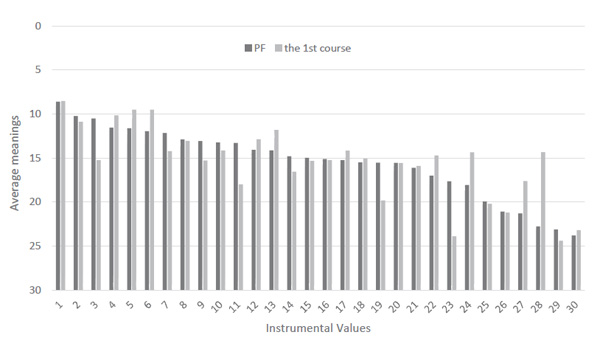

Figures 1 and 2 represent the dynamics of the terminal and instrumental values among the students. As one can see, the average meanings, weight, and ranking order of some values changed after a year of study in Russia. We have written about some aspects of our study in previous publications, where we analyzed the changes in ranks and hierarchic structures of the most prominent, high-rank values in detail (Maslova & Bui, 2014). In this paper, we focus attention on the statistically meaningful value shifts, revealed by the means of Wilcoxon T-criterion.

After a year, the statistically most prominent change was the increase in the adoption of the values Productive Life (p<0.05) and Materially Prosperous Life (p<0.01). At the tendency level, one can see the increased weight given to the value Pleasure, and decreased weight given to the values Peace and Creativity. Th us, we may state positively that after a year of study in Russia, some signifi cant changes took place in the value pattern of the Vietnamese students. An individualistic principle was strengthened in the goal values, while in the set of instrumental values, some of the Vietnamese people's traditional values increased in signifi cance, too.

Figure 1. Terminal value dynamics in Vietnamese students after the first year of study in Russia

Note. The closer the indicator is to zero, the higher the rank of value and its significance are. Statistically signifi cant shifts were found in two values, Productive Life and Materially Prosperous Life.

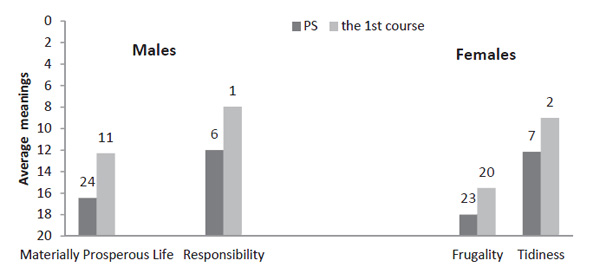

We asked whether there were some diff erences in the value dynamics between male and female Vietnamese students. In Figure 3, one can see which values showed a gender diff erentiation.

As seen from Figure 3, statistically signifi cant shifts in the value pattern of male students occurred in both terminal and instrumental values. Th e values of Materially Prosperous Life (p<0.05) and Responsibility (p<0.05) increased in signifi cance for them over the course of the year. In female students, goal values proved more stable, and only tool values displayed a shift–Frugality and Tidiness (p<0.05 for both).

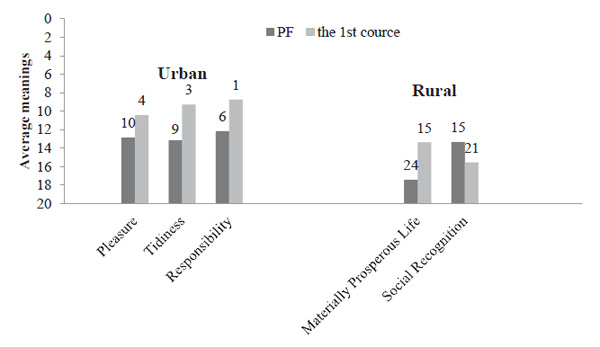

One of the aims of this study was to compare the value dynamics between students according to whether they came from a town or a village. Figure 4 shows the changes in value patterns of these two parts of the sample.

Figure 2. Instrumental value dynamics in Vietnamese students after one year of study in Russia

Note. Th e closer the indicator is to zero, the higher the rank of value and its signifi cance are. Underlined in the list below are the values whose change proved statistically signifi cant. Columns 1 to 30 represent these Instrumental values: 1. Education; 2. Good Manners; 3. Spirit of Community, Solidarity, Mutual Love and Interconnection; 4. Cheerfulness; 5. Responsibility; 6. Tidiness; 7. Modesty; 8. Industry; 9. Broad-Mindedness; 10. Gratitude; 11. Courageous Standing Up for Your Beliefs; 12. Collectivity; 13. Independence; 14. Simplicity; 15. Fidelity; 16. Tenderness, 17. Honesty; 18. Eff ectiveness; 19. Rationality; 20. Strength of Will; 21. Tolerance; 22. Frugality; 23. Contemplativeness; 24. Self-Esteem; 25. Ideals of the Revolution; 26. High Aspirations, Ambitions; 27. SelfControl; 28. Respect for the Elderly; 29. Fight against Imperfections in Yourself and in Other People; 30. Construction of Relations Based on Personal Emotional Bias.

Figure 3. Statistically signifi cant value shifts in male and female students. Th e numbers above each column stand for the ranking of the value

Figure 4. Statistically signifi cant value shifts in students coming from urban and rural settlements. Numbers above each column stand for the rank number of value

We see that students of both urban and rural origin change some of their personal values under the infl uence of a new culture. Th eir values shift in the direction of strengthening individualistic values, and decreasing values of a collectivist type, but these changes diff er in quality. Th e students of urban origin become more interested in the terminal value of Pleasure (p<0.05), and they become more oriented toward the instrumental values of Responsibility (p<0.05) and Tidiness (p<0.05). By contrast, students coming from villages become more oriented towards the Materially Prosperous Life (p<0.01). Th is result means that the acculturation process differs for rural and urban students. Th ey pay attention (to some extent) to diff erent aspects of life, and tend to attach diff erent weights to their personal values (Maslova & Bui, 2014).

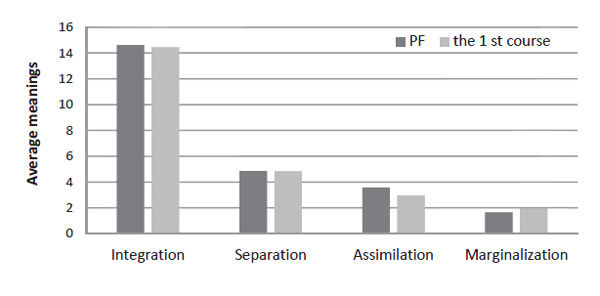

Figure 5. Relative strength of acculturation strategies found in Vietnamese students

The survey's next objective was to examine the value dynamics in the students according to their different acculturation strategies. Figure 5 shows the average intensity of the four strategies described by Berry et al. (2002) in our sample of Vietnamese students.

We proceeded from the assumption that the value orientation pattern would change most dramatically in students using the Assimilation strategy, and that minimal changes would be found in those using the strategy of Separation. In order to check this hypothesis, we applied Berry's technique to all the respondents. As a result, we assessed the acculturation strategy used by each student. But our intention to divide the sample according to the four types of acculturation could not be completed because 100 per cent of the respondents had the same predominant strategy–the strategy of Integration.

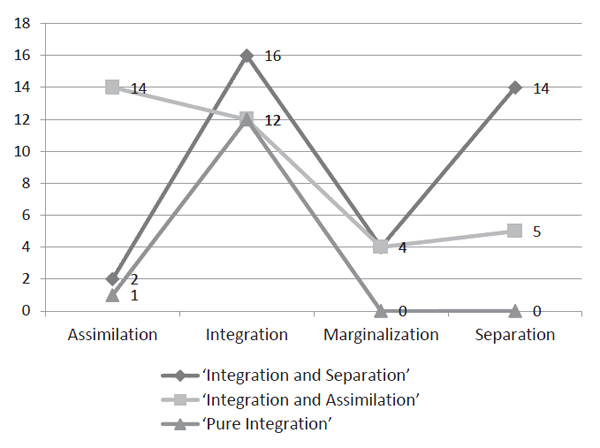

Nevertheless, the proportion of other strategies the students used varied to a certain extent, so we found it helpful to examine this proportion. With the use of cluster analysis, we divided the sample into three groups according to the relative expression of all four strategies (Figure 6). Now we could see the specific proportion of the four acculturation strategies in each individual, as well as in the sample as a whole. We refer to this inner proportionality as an acculturation profile. According to the pair of strategies most prominent in each individual (keeping in mind that the strategy of Integration remained the guiding principle in all cases), we were able to designate three main acculturation profiles, as follows:

- Pure Integration (found in 50 per cent of our respondents);

- Integration and Separation (found in 26 per cent of respondents), in which the general intention for integration with a new culture in some cases alternated with a separation tendency;

- Integration and Assimilation (found in 24 per cent of respondents), in which the general intention for integration with a new culture in some cases alternated with an assimilation tendency.

Figure 6. Acculturation profiles of the Vietnamese students

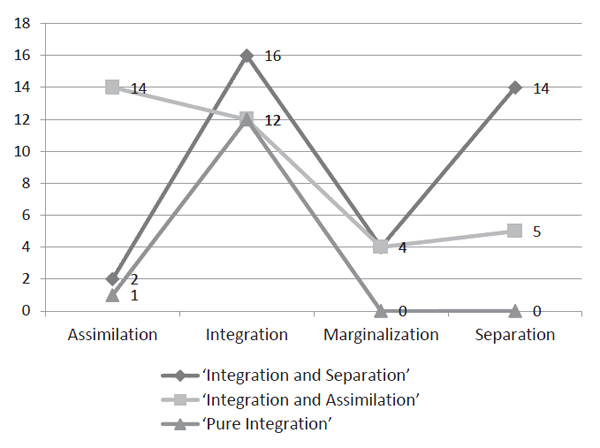

Figure 7. Statistically significant value shifts in students with different acculturation profiles

Analysis using the binomial criterion showed that the above three types of acculturation profile were equally common in male and female respondents, and in urban and rural students as well. The presence of a fourth strategy, Marginalization, did not show up in the sample to any significant degree.

The dynamic of value changes in subjects with different profiles was a surprise for us. The quantity of value shifts was most prominent (average=8) in the respondents with the Integration and Separation profile, leaving the owners of other profile types far behind. Only three shifts on average were found in students with the Pure Integration profile, and only two in students with the Integration and Assimilation profile. That result means that the value system in students with the profiles of Pure Integration, and Integration and Assimilation, proved more stable than in those with the Integration and Separation profile.

Figure 7 represents the spectrum of value shifts in respondents with all types of acculturation profiles. One can clearly see that in respondents with the Pure Integration profile, the significant shifts affected only instrumental values. They displayed an increased ratio of Tidiness (p<0.01) and Frugality (p<0.05), and a decrease of Respect for the Elderly (p<0.05). In students with an Integration and Assimilation profile, some shifts were seen not only in tool values, but in goal values as well. The weight given to Frugality increased in their value system (p<0.05), while the Peace value went down (p<0.05).

The most prominent value shift is seen in the subjects with the profile type of Integration and separation. The diagram shows the increase of such values as Broadmindedness (p<0.01), Respect for the Elderly (p<0.01), True Friendship (p<0.05),

Material Prosperity (p<0.05), and Happiness for Other People (p<0.05). At the same time, a decrease is seen in the values of Gratitude (p<0.05), Social Recognition (p<0.05), and The Beauty of Nature and Arts (p<0.05).

Discussion

How could it be that the system of value orientations changed in a more dramatic way in those students who were less open to a new culture, as compared to that of those who were more inclined towards intercultural relationships? Qualitative analysis of the whole body of data suggests that it could be due to the fact that the students belonging to the group Integration and Separation are more sensitive to acculturation distress; they feel more upset by the "value clash" and try to resist the upcoming changes.

In this painful situation, they need more attention and friendly concern, including support from their family members, friends, and compatriots. Maybe this need for support stands behind the fact that the values True Friendship (p<0.05) and Respect for the Elderly (p<0.01) had increased noticeably in this group of respondents. They may more often compare their native culture with the new one, discuss the differences, and reflect upon the new situation. This kind of reflection may be useful in the process of reassembling their whole value system. It may also be important that the instrumental value Broad-mindedness has increased in this group (p<0.01), indicating a willingness to understand another people, and to respect their habits and customs.

On the other hand, respondents with the profiles of Pure Integration, and Integration and Assimilation, feel themselves more confident and independent in a new culture; they can rely on themselves in complex circumstances. So, in the students with a profile of Pure Integration, the values Respect for the Elderly (p<0.05) and True Friendship (p<0.01) decreased in their significance, but growth was found in Responsibility (p<0.1) and Effectiveness (p<0.1).

All this is only a hypothesis. For a more confident answer to the question "Why did the students with more flexible and open acculturation strategies tend to have more stable value systems than the students who were inclined to more restrained acculturation strategies?" , an additional study may be required.

Our results are consistent with earlier findings of gender differences in the process of adaptation to a new socio-cultural environment in Latin-American students (Maslova & Tapia, 2012; Maslova, 2012), where female students showed a greater adherence to traditional values than males in the same communities.

It would be of interest for us to compare our results with the results of other studies of dynamics of personal values in Vietnamese people, but we could not find any longitudinal study on this matter. The only one close to our topic was a paper by K. Sh. Le (1998), who studied the changes of values in Vietnamese people in the course of time by comparing subjects of different ages. This author used the Rokeach method, just as we did, but unlike us, he conducted his study on subjects resident in Vietnam, but belonging to different generations.

In his study, K. Sh. Le revealed a greater incidence of individualistic tendencies in young people as compared to the elderly of population in Vietnam, along with a decrease in some kinds of traditional values, such as Frugality and Respect for the

Elderly; these lost their significance among the young generation, and even tended to be rejected in this strata (Le, 1998). As shown above, we found a similar tendency in the subjects of the present study, after a year of their living in Russia and studying in Russian universities. We found a significant increase of individualistic values in these subjects (such as Materially Prosperous Life and Productive Life), but at the same time, no decrease was found in traditional Vietnamese values such as Frugality and Tidiness. Moreover, their presence became more prominent in the subjects of our study, as shown in Figure 2, while another traditional value, Respect for the Elderly, displayed different types of dynamics depending on the acculturation profiles of our subjects (see Figure 7).

This dissociation between the results of the two studies may be due to the difference in the initial experimental conditions. Namely, Le conducted his study among Vietnamese residents belonging to different generations, while our own study was comprised of a sample of the same age, i.e. young Vietnamese students who were separated from their native soil and had the urge for acculturation to a completely new cultural environment. We may therefore assume that our study was rather innovative in its specific combination of objective and method, especially in this country.

Conclusions

The present study enables us to draw the following conclusions:

-

In the course of acculturation of Vietnamese students in Russia, the significance of personal goal values, primarily Material Prosperity and Productive Life, has increased in a significant way, as well as some tool values (Tidiness and Frugality) traditional in the Vietnamese people.

-

Gender serves as a mediating factor partially determining the value dynamics. The value system of male students is more dynamic, with changes affecting both their goal and tool values. In female students, only tool values were affected by changes due to the acculturation process.

-

The subjects' original living environment (urban or rural) is another factor mediating the value shift. Students from towns and villages turn their attention to different types of new cultural values, and adopt them in different ways. The town-born students begin to pay more attention to the Pleasures value, while those coming from villages turns mostly toward a Materially Prosperous Life.

-

The acculturation profile is one more factor mediating the personal value dynamics. The value system of students with an Integration and Separation profile changed to a larger degree than that of students with profiles of Integration and Assimilation, and Pure Integration.

References

Berry, J.W., Poortinga, Y.H., Segall, M.H,. & Dasen, P.R. (2002). Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications, (2nd Edition) N.Y.: Cambridge University Press.

Hồ Sỹ Quý (2010). Mấy vấn đề triết học giá trị và sự biến đổi giá trị trong bối cảnh toàn cầu hóa [Philosophical issues of values and the change of values in the context of globalization]. Nghiên cứu khoa họ c [Scientific research]. Hanoi.

Kudrjashov, A.F. (1992). (Ed.).Luchshie psihologicheskie testy [The best psychological tests]. Petrozavodsk: Petrokom.

Le, K.Sh. (1998). Psihologicheskie osobennosti cennostnyh orientacij sovremennoj v'etnamskoj molodezhi [Psychological Characteristics of Value Orientation of the Contemporary Vietnamese Youth]. Moscow.

Lebedeva, N.M. & Tatarko, A.N. (2007). Cennosti kul'tury i razvitie obshhestva . [Cultural Values and Evolution of Society]. Moscow: Izd. Dom GU HSE.

Lebedeva, N.M. & Tatarko, A. N. (Eds.). Strategii mezhkul'turnogo vzaimodejstvija migrantov i naselenija Rossii (2009). Sbornik nauchnyh statej. [Strategies of Intercultural Interaction of Migrants With the Russian Population] Moscow: RUDN.

Leontiev, D.A. (1993). Ocherk psihologii lichnosti. [Studies in Personal Psychology]. Moscow.

Maslova, O.V. (2012). Osobennosti mezhkul'turnoj adaptacii latinoamerikanskih studentov v Rossii [Peculiarities of Psychological Adaptation of Latin American Students to a New SocialCultural Environment]. Vestnik Rossiiskogo universiteta druzhby narodov. Seriya: Psikhologiya i pedagogika [Bulletin of Peoples' Friendship University of Russia. Series Psychology and Pedagogics], 2, 50–59.

Maslova, O.V. & Bui, Duk T. (2014). Dinamika cennostej v'etnamskih studentov v Rossii [Dynamics of Values in Vietnamese students in Russia]. Vestnik Rossiiskogo universiteta druzhby narodov. Seriya: Psikhologiya i pedagogika [Bulletin of Peoples' Friendship University of Russia. Series Psychology and Pedagogics], 1, 49–55.

Maslova, O.V. & Bui, Duk T. (2014). Izmenenie cennostnyh orientacij u gorodskih i sel'skih vjetnamskih studentov v Rossii [Value Orientations in Urban and Rural Vietnamese Students and Their Changes in Russia]. Vestnik Rossijskogo universiteta druzhby narodov. Seriya: Psikhologiya i pedagogika [Bulletin of Peoples' Friendship University of Russia. Series Psychology and Pedagogics], 4, 24–33.

Maslova, О.V. & Tapia López, J.M. (2012). Cambio de valores de la persona en el proceso de adaptacion intercultural [The Change of Personal Values in the process of intercultural adaptation]. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1, 593–596.

Phạm, Minh Anh (2012). Định hướng giá trị của thanh niên ở những vùng đô thị hóa trong thời kỳ hội nhập và phát triểnmột hướng nghiên cứu chuyên ngành [Value orientations of youth in urbanized areas in the period of integration and development — a direction of specialized research]. Tạp chí xã hội hoc [Journal of Sociology], 5, 45–47.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The Nature of Human Values, N.Y.: The Free Press.

Yanickyi, M.S. (2012). Cennostnoe izmerenie massovogo soznanija [Value Dimension of Mass Consciousness]. Novosibirsk.

Zhuravleva, N.A. (2013). Psihologija social'nyh izmenenij: cennostnyj podhod. [Psychology of Social Changes: A Value-Based Approach]. Moscow: RAS Institute of Psychology.

To cite this article: Maslova O.V. (2018). Value shifts in Vietnamese students studying in Russia. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 11 (2), 14-24.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.