Detecting and overcoming infantilism in students at teachers colleges

Abstract

Background. The variety of preschools is one of the primary issues of contemporary early education in Russia. The traditional approach focuses on the transmission of knowledge, patterns of social behavior, and assumes teacher-centered interaction between child and teacher. The developmental approach focuses on developing the child’s abilities and using cultural tools, rather than just transmitting educational content. A comparison of different preschool approaches and outcomes may help in choosing the most suitable one for each child.

Objective. The aim of this study is to identify the connection between approaches in preschool and children’s school readiness.

Our hypothesis is that the traditional approach and the developmental approach provide different school readiness outcomes.

Design. Ninety-two preschool students (51 boys and 41 girls) aged six to seven were involved in this study. These children attended preschools in the western and southwestern districts of Moscow. Six preschool psychologists and teachers were interviewed. The research was conducted between 2011 and 2013.

Results: An empirical study proved that most children achieve a high level of cognitive readiness, can interact with successfully peers, and can control aggression; however, they also have difficulties with cooperative relations with their teacher and with expressing their opinion. A comparison of school readiness outcomes of the traditional and developmental approaches showed that the children who attended a preschool with the developmental approach demonstrated a higher level of school readiness: they are able to ask for help, to coordinate their creative intentions with peers, and to empathize with them. Their self-consciousness is greater than that of their peers who are educated under the traditional approach. Also, they demonstrate a greater voluntary readiness for school. Meanwhile, children who attended preschools with the traditional approach demonstrated а higher level of verbal-logical reasoning.

Received: 25.12.2016

Accepted: 11.11.2017

Themes: Educational psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2018_1/psych_1_2018-7_Podolskaya.pdf

Pages: 84-94

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2018.0107

Keywords: infantilism, overcoming academic and professional infantilism, self-actualization, internality, structural components of infantilism, conditions to overcome infantilism

Introduction

Training professional teachers is both a priority and a prerequisite to ensuring that the education of future generations is of high quality. One of the steps that aspiring teachers need to take to become a professional is their self-actualization in theprofession, that is, developing an awareness of the opportunities that the teaching profession provides for self-development.

One of the obstacles to developing professionals which is encountered among students in higher education is a special form of infantilization, here described as academic and professional infantilism. While reviewing academic and professional infantilism as a complex phenomenon with many root causes, we define it as a special, destructive method of attempted personal self-fulfillment in educational and professional environments, under the influence of certain mental conditions and mechanisms.

The phenomenon of infantilism has become a trend in the younger generations as a whole. The identifying factor of this phenomenon, in the eyes of experts, is avoidance of choice and the relegation of responsibility for decision making to others. The social role of the 4eternal child” or “kidult” exempts a person from responsibility for their behavior (A.G. Asmolov).

Numerous papers in the history of psychology as well as more recent works by domestic and foreign scientists have analyzed infantilism. Foreign psychologists such as E. Lasegue, G. Anton, P. Lorrain, S. Freud, G. Stutte, E. Kraepelin, and R. Corbo have sought to explain the concepts, classify the characteristics, and advance possible reasons for the origination and development of infantilism. In domestic psychology, more focus has been placed on studying the problems of infantilism, as seen in the papers of L.S. Vygotsky, V.V. Kovalev, V.V. Lebedinsky, and others.

Infantilism is understood as retention of the physical and/or psychological characteristics of childhood into a relatively advanced age; as childishness combined with an incomplete mind (E. Brissaud); and as arrested emotional development (R. Corbo). Psychoanalysts have explained infantilism as a manifestation of the unconscious, as immaturity of mental protections of the personality, and as a disorder of hormonal activity (K. Abraham, S. Freud, C.G. Jung).

Infantilism has been described as a disorder of involuted child development (L.S. Vygotsky); as a form of intellectual activity disorder that is part of general arrested mental development (I.B. Shenfil, M.I. Buyanov); as arrested mental development (V.V. Lebedinsky, E.P. Ilyin); and as a special characteristic of the physical and socio-psychological development of adolescents (E.I. Isaeva, A.E. Lichko).

Method

In our study, we have posited the following characteristics of infantilism: underdevelopment and immaturity in the emotional-volitional sphere (i.e., emotional immaturity, lack of self-control, lack of discipline, weakness, lack of initiative, and vague life and/or professional goals) (M. Bleuler, T. Simson, Ya.A. Egolinsky); reluctance to engage in work and low work motivation (Yu.N. Davydov); a specific system of values and delay in moral maturation (A.A. Bodalev,Yu.N. Davydov); a hedonistic pursuit of entertainment (K. Abraham, S. Freud); a low level of reflexive capabilities (M.I. Buyanov); unusually dependent, parasitic, and irresponsible behavior (Yu.N. Davydov, G.E. Sukhareva); disordered and chaotic behavior (G.E. Sukhareva); and a lack of desire to achieve (M.I. Buyanov, T. Simson).

By academic and professional infantilism in students, we mean a destructive method of attempted personal self-fulfillment within the learning and pedagogical process. It is not just about manifestations of infantilism itself, but also about predisposition towards certain forms of self-destruction in academic and professional activity.

Academic and professional infantilism is characterized by negative attitudes towards academic and professional activities, an excessive exactingness towards the environment, active and passive resistance to the educational process, the lack of an appropriate view of ones own professional development, the lack of professional and life plans or any real ways to achieve such plans if they exist, and a lack of personal orientation in professional and academic activity.

The objective of this paper is to define the nature and manifestations of infantilism and the conditions for overcoming it in university students.

We assumed that the psychological and pedagogical requirements for overcoming academic and professional infantilism in students at higher educational institutions are associated with the implementation of a specially developed psychological and educational program, the developmental nature of which is relevant to the structural components of academic and professional infantilism, with the leading ones being:

-

The lack of any real capability or inclination to perform a particular activity (in this case, pedagogical activity) and, as a result, markedly diminished or complete lack of interest in the subject being studied, regardless of how and how well that subject is taught;

-

The lack of an appropriate personal position in relation to ones own professional development, no professional and life plans, and no real ways to achieve such plans if they exist;

-

A disproportionately high claim to have mastered the structural and content-related processes of organizing field-specific (pedagogical) education, which is out of line with ones own efforts to become immersed in the educational challenge.

Psychological and pedagogical provisions for overcoming learning and professional infantilism in students of higher educational institutions are necessary to develop students in the emotional-volitional sphere, to improve their system of values, to increase their motivation for work and learning, to develop their reflective capabilities, to increase their desire for achievement, etc.

A working structural and procedural model of infantilism that determines the place, role and interaction of its various components has been developed based on a theoretical study of academic and professional infantilism. This model can be described as an integral, dynamic, and varied educational process that includes cognitive, evaluative, emotional, axiological, motivational, and reflective elements.

This model of academic and professional infantilism in students highlights a negative attitude towards the following: common standards accepted in society and in the group; the significance of personal goals and standards; matching selfperception with personal goals; quality self-esteem; the ability to think reflectively; assessment of personal effectiveness in any given field of activity, whether one is confident or not about ones own competence and ability to organize and perform actions needed for certain achievements. We conducted a pilot study of academic and professional infantilism, involving 167 1st" through 5th-year students at Moscow State Pedagogical University.

The group of students who displayed pronounced manifestations of learning and professional infantilism amounted to approximately 45% of the sample. These students were selected on the basis of the results of psychological diagnoses and the expert opinions of their teachers. We used diagnostic measures consisting of psychological and diagnostic methodologies delineated in the following works: “Level of subjective control” by J. Rotter, as adapted by E.F. Bazhin (the questionnaire contains 44 statements and requires answers using a six-point scale); “Need for achievements test”, by Yu.M. Orlov (the questionnaire contains 23 statements which are to be accepted or rejected by the subjects); “Diagnostics of motivational structure of personality”, a technique by V.E. Milman (the test contains 14 statements, each with eight options for the answer); “Level of infantilism evidence” (LIE), a questionnaire by A.A. Seriogina (the questionnaire include 48 questions; the subject has to choose one of four possible answers).

The results of the diagnostics allowed us to divide the students into four groups (non-infantile, slightly infantile, moderately infantile, and highly infantile) displaying differing levels of academic and professional infantilism in accordance with the data provided by the LIE questionnaire. 32% of subjects were allocated to the noninfantile group, 23% to the slightly infantile group, 27% to the moderately infantile group, and the remaining 18% to the highly infantile group.

The following indicative qualitative and quantitative differences between the groups were identified and described on the basis of methodological scales.

Group 1 — non-infantile — This group was characterized by high levels of development in the emotional and volitional sphere, well-developed self-control, clear and achievable aims; discipline, courage, proactivity, resoluteness; high work motivation, a sustained desire to learn; a prevalence of moral over material values, firmness of principles, belief in the significance of health, love, and interesting work; a strong will and high valuation of responsibility; a lack of interest in entertainment, a link between pleasure and evaluating the consequences of an action; a high level of self-reflection; an active pursuit of rational behavior in organizing their lives; an active and ongoing attempt to overcome obstacles; a high degree of independence and autonomy. This group valued the need to achieve at about 60% of the maximum possible value.

Group 2 — slightly infantile — This group displayed a degree of flawed selfcontrol. The students were characterized by an ability to control their emotions which is situational and unstable; an ability to set life goals, but with some difficulties in planning ways to achieve them; by high work motivation; a focus on favorable circumstances in their learning activities; situational zeal in their studies; a prevalence of moral values over material values; a situational willingness to sacrifice their principles for the sake of satisfying their needs; a sense of enjoyment which is not always tied to evaluating the consequences of their actions; a desire to have pleasure in everything; situational reflection; a rather vague pursuit of order and rationality; an intention to avoid difficult situations; limited success in overcoming their own weaknesses; relative independence, but low zeal; and a low sense of personal responsibility in all spheres of life. This group valued the need to achieve somewhat lower than Group 1, at 54%.

Group 3 — moderately infantile — This groups is characterized by a limited ability to control their emotions; moderate impulsiveness; weak self-control; diffuse life goals and a lack of confidence in the possibility of achieving them; randomness in planning and the means adopted to achieve objectives; lack of discipline; low work motivation; low zeal about their studies; waiting for the help of others; a tendency to place material values above moral values; a potentiality to break the law; a pursuit of fun without thinking; seeing fun as one of the purposes of life; a potential to engage in unlawful forms of entertainment; a proclivity towards being better at assessing the consequences of an action than the reasons for performing the action; a penchant for spontaneity and rashness; a tendency to find order stifling; passivity in the face of difficulties; a tendency to adopt a dependent position; reluctance to assume responsibility; a preference for civil marriage; and a high degree of dependency. This group valued the need to achieve the lowest among the groups, at about 54% of the possible maximum values.

Group 4 — highly infantile — This group was characterized by an extremely poor ability to control their emotions; impulsiveness; lack of self-control; uncertain life goals and plans; lack of discipline, lack of initiative, passivity, indecisiveness; low motivation to work; seeing university life as an opportunity to have a good time; an unwillingness to learn or acquire knowledge if they are provided with material support; complete absence of desire to develop a career; an extreme preference for recreation and entertainment over work; an extreme preference to place material values above moral and ethical values; a propensity to breach the law to satisfy their own needs; a desire to get everything at once here and now “for free”; failure to analyze the consequences associated with having fun; a tendency to see “having fun” as the purpose of life; a focus on day-to-day existence rather than longer term planning; very low reflective capabilities; irritation when faced with restrictions; passivity towards difficulties; apparent dependency in all spheres of life, lack of autonomy, irresponsibility; a belief that parents or relatives should provide everything necessary for a dignified existence; and a preference for non-official marriages. This group valued the need to achieve at about 45%.

Results

By way of psychological and pedagogical provisions for overcoming infantilism, we developed a special comprehensive program, the developmental nature of which is relevant to the structural components of infantilism and focused on the development of students in the emotional and volitional sphere as well as in their systems of values, learning and work motivation, reflective abilities, and their desire to achieve.

The process of overcoming infantilism consists of three stages. The first stage involves a person becoming aware of their own problem, i.e., becoming dissatisfied and developing the motivation to find solutions. The second stage involves understanding the reasons for failure, identifying the origins of a problem and developing a new model of activity. During this stage the person becomes aware of his/her behavior and develops a new behavioral model to eliminate or reduce the infantilism. Finally, the third stage involves mastering and internalizing the new model, analyzing its results.

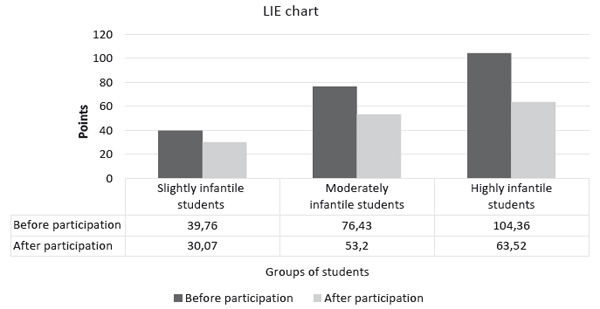

Figure 1. Changes in levels of infantilism according to the LIE questionnaire in three groups of students, before and after participation in the program

The implementation of the program involved three groups of 1stthrough to 5thyear students from Moscow State Pedagogical University (50 students in total). Of these, 13 students were classified as slightly infantile, 26 as moderately infantile and 11 as highly infantile.

Figure 1 shows the changes in the level of infantilism according to the LIE questionnaire in the three groups of students, before and after their participation in the program.

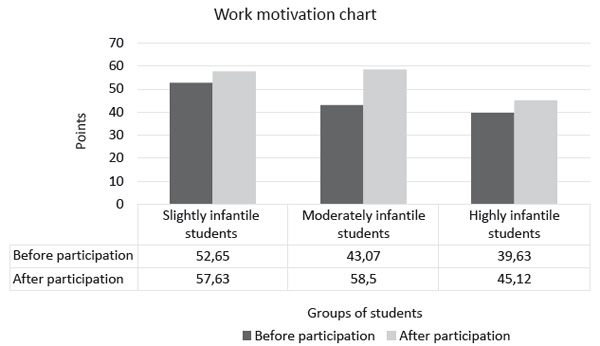

Figure 2. Changes in values for work motivation according to V.E. Milmans technique, in three groups of students before and after participation in the program

The group of slightly infantile students scored 39.76 points before participation in the program. After participating, this value decreased to 30.07 points, which indicates that the severity of their infantilism dropped to the border between infantilism and non-infantilism. We think such a change is positive and worthy of notice. The group of moderately infantile students showed an average score of 76.43 points before participating; the change was again positive, and the mean infantilism value dropped to 53.2 points. According to its infantilism scores, however, this group cannot be considered to be only slightly infantile. Highly infantile students scored an average of 104.36 points on the LIE questionnaire before participating in the program. After participating, this value dropped significantly to 63.52 points, a score which corresponds to moderate infantilism according to the LIE questionnaire.

According to “Diagnostics of Motivational Structure of Personality” by V.E. Milman, shown in Figure 2, work motivation values have also changed.

Work motivation values have increased in all groups. The mean value of 52.65 points in the group of slightly infantile students has risen to 57.63 points. The work motivation of the group of moderately infantile students reached 58.5 points, starting from 43.07 points prior to their participation in the program. This indicates an even more positive trend in this group, when compared with the group of slightly infantile students. The work motivation value of highly infantile students rose from 39.63 points to 45.12 points. These changes show a positive trend, which also confirms the effectiveness of the psychological and pedagogical provisions we used. The changes in internality values for groups of infantile students according to J. Rotters LSC technique are shown in Figure 3.

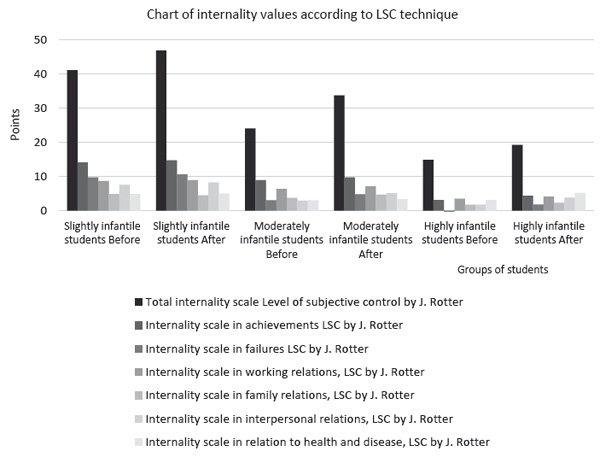

Figure 3. Changes in internality values according to J. Rotter’s LSC technique for groups of infantile students

Value changes on the scale of this technique in the group of slightly infantile students are as follows: TI (Total internality) scale: the respondents scored 41.07 points before participation and 46.8 points after participation. AI (Achievement internality) scale: 14.11 points before participation and 14.72 points after, a small positive increase. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicates the absence of pronounced change, which shows that this increase is insufficient to determine a reliably prevailing change. FI (Failure internality) scale: the respondents’ average score was 9.73 points before participations, and rose to 10.63 points after. WI (Working relation internality) scale: the figure increased from 7.61 points to 8.25 points after completion of the program. FI (Family relations internality) scale: the value declined by 0.41 points (from 4.92 points at the beginning of the program to 4.51 points at the end), while the Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicates the absence of pronounced change. HI (Health area internality) scale: there is a slight positive increase (from 4.91 to 4.97 points), but the Wilcoxon signed-rank test shows no pronounced changes.

Based on these data, we can assert the predominance of positive trends in the figures that characterize internality, and, therefore, a reduction of infantile manifestations in this group of students.

The group of moderately infantile students displays the following trend: TI scale: 24.05 points before correction of infantilism and 33.7 points after. AI scale: this figure increases significantly from 8.93 to 9.75 points. FI scale: the internality figure increased from 3.09 to 4.79 points. WI scale: the initial figure increased from 6.36 to 7.16 points. II scale: increased significantly from 2.93 to 5.13 points, which indicates the positive trend of the changes. Fall scale: reached 4.68 points after participation in the program, up from 3.75 points before participation, though the Wilcoxon signed-rank test again shows no pronounced changes. HI scale: 3.09 points before correction of infantilism and 3.41 points after correction.

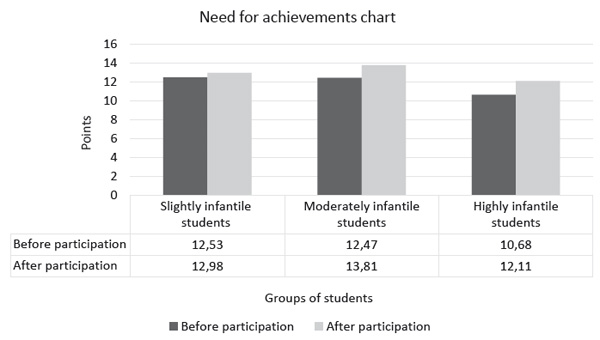

Figure 4. Changes in values characterized by the need for achievement.

Thus, we can argue the predominance of positive trends regarding internality figures for this group.

TI scale in the group of highly infantile students: the figure rose from 14.89 to 19.2 points. AI scale: 3.1 points at the beginning of the program and 4.41 points at the end. Fall scale: rose from 0.84 points to 1.84 points, while the Wilcoxon signed-rank test shows no changes. WI scale: increased from 3.52 points to 4.17 points. II scale: increased from 1.73 points to 3.82 points; the Wilcoxon signed-rank test shows no pronounced changes. Fall scale: the figure increased from 1.78 points to 2.35 points, which also makes it impossible to talk about significant changes in terms of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. HI scale: increased from 3.15 points to 5.23 points.

Thus, this group is also dominated by positive changes in internality value. Changes in values characterized by the need for achievement are shown in Figure 4.

This figure rose in all three groups that participated in the program, although the Wilcoxon signed-rank test shows a significant change only in the moderately infantile group: the slightly infantile group scored 12.53 points before participation and 12.98 points after; the moderately infantile groups score increased from 12.47 points to 13.81 points, and the score of the slightly infantile group increased from 10.68 points to 12.11 points.

The results suggest that the psychological and pedagogical provisions we developed contributed to overcoming infantilism in students, future teachers.

Conclusions

-

Infantilism in learning and professional instruction is regarded as a destructive strategy of personal self-fulfillment of students in academic and professional environments, which manifests as a lack of motivation for professional development; as the establishment of a system of negative values in relation to personal development; as an inadequate attitude to real-life crisis situations; as academic and social passivity; as a tendency to refuse help and support by teachers; as indifference to ones own academic progress; and as an inability to apply knowledge in practice.

-

The structural and dynamic model of infantilism includes the following: a psychological component (immaturity in the emotional and volitional sphere, low desire to achieve, lack of motivation in work and education, poorly developed reflective skills), a social component (dependence on others when making decisions or taking action, chaotic behavior, dependency, hedonism), and a physical component.

-

Psychological and pedagogical prescriptions for overcoming academic and professional infantilism in students are associated with the implementation of the program, the developmental nature of which is relevant to structural components of infantilism and is focused on the development of students in the emotional and volitional sphere, their systems of values, their motivation for work and education, their reflective abilities, their desire to achieve, etc. It is necessary to distinguish external and internal conditions for overcoming academic and professional infantilism in students. External conditions includeorganized activities aimed to decrease infantilism among students, such as professional orientation. Internal conditions are related to goal-directed influences on personal features of students during correction of infantilism, such as reflectivity, work and learning motivation, and value orientation.

-

Three stages in overcoming infantilism are to be distinguished: The first stage involves a person becoming aware of his/her problem. The second stage involves understanding the reasons for failure, identifying the origins of a problem, and developing a new model of activity. The third stage involves mastering and internalizing the new model, evaluating and analyzing the results achieved.

References

Apraxina, N.D.(2008). Preodolenie uchebno-professionalnogo infantilisma studentovvprotsesse sotsio-kulturnogo razvitiya v vuze [Overcoming of students’ learning-professional infantilism during socio-cultural development at university]. PhD thesis abstract, Moscow.

Asmolov, A.G.(2002). Po tu storonu soznaniya: metodologicheskie problemy neklassicheskoypsikhologii [Beyond consciousness: methodological problems of non-classical psychology]. Moscow: Smysl.

Davydov, Yu.N., & Rodnianskaya, I.B. (1980).Sotsiologiya contrakultury (Infantilizm как tipmirovospriyatiya i sotsialnaya bolezn)[Sociology of the counter-culture: (Infantilism as a type of perception of the world]. Moscow: Nauka.

Ivanov, I.A.(2002). Znachenie sovremennoy diagnostiki psikhicheskogo infantilizma v usloviyakh voennoy sluzhby [The significance of modern diagnostics of mental infantilism under conditions of military service]. Mezhdunarodnyj medicinslij zhurnal [International MedicalJournal], 8(1-2),63-66.

Klein, D.(1970). Man-child: A study of the infantilization of man. N.Y.: McGraw-Hill.

Mitina, L.M. (1998) Psikhologiya professionalnogo razvitiya uchitelya [Psychology of the teacher s professional development]. Moscow: Flinta.

Podolskaya, T.A., & Utenkov, A.V.(2016). К probleme diagnostiki i preodoleniya infantilizma u studentov pedagogicheskikh vuzov [On diagnostics and overcoming infantilism among students at teachers colleges]. In: Pedagogicheskiy professionalism: suf, soderzhanie, razvitie [Teachers’ professionalism: Essence, content, development](pp. 441-445). Moscow: MANPO.

Podolskij, A.(2012). Russia. In: J.J. Arnett (Ed.). Adolescent psychology around the world (pp. 321-335). N.Y.: Psychology Press.

Podolskij, A.(2012) Development and Learning. In: Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning (pp. 944-950). N.Y., Heidelberg: Springer.

Shadrikov, V.(2013) The role of reflection and reflexivity in the development of students abilities. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 6 (2), 55-64. doi: 10.11621/pir.2013.0205

Shaporeva, A.A.(2002). Analiticheskiy obzor issledovaniy poniatiy psikhicheskaya zrelosf, narushenie razvitie, i psikhicheskiy infantilizm [Analytical review of exploration of the concepts of psychological maturity, developmental disorder, and psychological infantilism]. Zhurnal prikladnoi psihologii. [Journal of Applied Psychology], 3.

Utenkov, A.V.(2014). Psikhologo-pedagogicheskie usloviya korrektsii infantilizma u studentov pedagogicheskikh vuzov [Psychological-pedagogical conditions of correcting infantilism among students at teachers colleges]. PhD thesis, Moscow.

T. A. Podolskaya, А. V. Utenkov, Yurevich A.V., Ushakov D.V.(2013). The Psychological dynamics of modern Russian society: an expert estimate. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 6, 21-34. doi: 10.11621/pir.2013.0102

Zimniaya, I.A.(2003). Klyuchevye kompetentsii — novaya paradigma rezultata obrazovaniya [Key competencies — A new paradigm of the result of education]. Vysshee obrazovaniesegodnia [Higher Education Today], 5,(pp. 3-18)

To cite this article: Podolskaya T.A., Utenkov A.V. (2018). Detecting and overcoming infantilism in students at teachers colleges. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 11 (1), 84-94.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.