A new perspective on autism: Rita Leal School

Abstract

Guided by the principle that scientific knowledge should serve to transform reality and create suitable conditions of life for all, the Portuguese Association for Relational-Historical Psychology (APPRH) founded a school named RITA LEAL (RLS), with a therapeutic purpose based on new perspectives for treating autism — perspectives quite different from instrumental and behavioral learning programs. The Rita Leal School (Leal, 1975/2004, 1997, 2005, 2010) is rooted in the theory that mental development is based on a mutually contingent emotional relationship, while it underwrites Vygotsky’s concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and Mediation (1930/2004, 1934/2009). Learning to read is a complex process which individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) master slowly and with difficulty. We analyzed the process of learning to read of two ASD children accompanied by peers without special educational needs, aiming to pinpoint distinct aspects of their progress. We used the Observer Software Program to collect and analyze observations of their performance, which were understood as data to be classified according to previously specified codes. We believed we could demonstrate that, especially in the case of ASD children, learning is dependent on contingent responses and adequate levels of mediation. The technical team at the RLS has continuous clinical supervision. That is because we believe this supervision is what permits the team to undergo a process of de-centering, becoming more empathic and accessible to the autists. This makes the team’s intervention more efficient, because it becomes more aware of each autist’s individual characteristics, and therefore more available to respond to the autist’s needs.

Received: 05.08.2016

Accepted: 21.09.2016

Themes: Clinical psychology; 120th anniversary of Lev Vygotsky

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2016_4/psychology_2016_4_13.pdf

Pages: 163-192

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2016.0413

Keywords: autism, contingent emotional development, mediation, zone of proximal development

Introduction

The term “Autism” was first introduced by Paul Eugen Bleuler (1911), who described it as a symptom of schizophrenia, understood as a “shutdown of reality and (...) predominance of inner life” (Bleuler, 1911/2005, p. 109).

In 1943 Leo Kanner published the first description of child autism: “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact.” He considered autism a rare neurological condition distinct from schizophrenia: “the inability to relate to others beginning in the first years of life” (p. 242). Most of the children he observed developed language, but did not employ it for communication with others (Kanner, 1943). He described them as deeply sick and isolated from society, and as the product of a toxic environment provided by their caretakers. Kanner’s hypothesis, which assigns blame to parents for autism, became common in the 1940s and 1970s.

Contemporaneously, Hans Asperger published an article entitled “Autistic Psychopathy in Childhood” (1944). Having observed a more diversified group, he described cases which were very similar to those presented by Kanner, and stated that autism should be conceptualized as a spectrum, ranging from “highly original genius to the mentally retarded” (Asperger, 1944/1991, p. 74). His intention was not only the habilitation of autists, but better identification of their capabilities and recognition of their potentialities.

While some of the children Kanner described did not use language, and others showed disturbances in communication, those observed by Asperger “talked like adults” (p. 39), although they showed a deficiency in social interaction and communication (Asperger, 1944/1991).

In 1980, the American Academy of Psychiatry (APA) again advanced the classic concept initially described by Kanner, and classified autism as a Comprehensive Development Disorder (3rd ed.; DSM-3; APA, 1980). But, in 1984, the ninth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) described autism as a form of psychosis, beginning in childhood and tending to develop into schizophrenia (Artigas-Pallarès & Paula, 2012). After this period, the two most used systems of diagnostic classification considered autism a category distinct from other psychiatric pathologies.

A 2013 reformulation by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) brought significant changes in the diagnosis of autism. All subcategories were replaced by the more comprehensive diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The main criteria are: “persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction in multiple contexts”; “restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests and activities”; and “the symptoms must be present in the early stages of development” (5th ed.; DSM-5; APA, 2013).

Several levels of severity were defined which describe the criteria for treatment: needing help; needing substantial help; and needing very substantial help (5th ed.; DSM; APA, 2013). Progress seems to stem mostly from the enhanced number of levels of help envisaged, which define a wide range of diagnostic differentiation (though rather simplistic and unclear), and point to some sort of external (social) aid as a valid instrument for future research.

Nonetheless, we believe that the scientific community still lacks a strong and distinctive theoretical reference point leading to a clear definition of a clinical treatment method for ASD. Looking carefully at the latest diagnostic criteria presented, which focus on isolated symptomatic behavior and the discrimination of the levels of severity of disturbance, this new definition maintains the underlying thesis of a biological cause, and the conviction that the social environment can merely mitigate the intensity of various autistic behaviors. Thus the temptation persists to view autism as split into distinct parts, and not as a disorder which has a relational origin, and a systemic and unique format. This confusion has existed from the beginning, as shown in the ideological duality found in the therapeutic community — biological vs. social, materialist vs. idealist — and in different treatment projects introduced over time. Thus, multiple therapeutic treatment methods for autism were applied: psychoanalytical, conditioning, psychopharmacological, shock treatment, family psychotherapy, and their multiple combinations. In most cases, not much symptomatic change occurred.

Rita Leal School

The Rita Leal School (RLS) project posits the evolutionary or transformational character of pathological phenomena and considers the ASD individual an active element in the treatment process. The RLS accepts DSM-5 and ICD-10 criteria as guidelines for observation, evaluation, and training; nonetheless, it does not deem them sufficient for understanding the real possibilities for clinical treatment.

The RLS maintains that mental development is based on a mutually contingent emotional relationship (Leal, 1997/2004, 1993, 2005), while underwriting Vygotsky’s concepts of Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and Mediation (1930/2004, 1934/2009), and Quintino-Aires’ (2001) understanding of relational-historical clinical intervention procedures with autists.

Relational-Historical Theory posits the relational origin of higher nervous function structures. In line with this theory, Quintino-Aires called the process of construction of the human mind “psycho-poiesis” (2016, p. 302), indicating that this process proceeds through action in the context of an interpersonal relationship mediated by the culture in which the individual is immersed, and which is equally the culture of his responders (p. 302). Vygotsky (1934/2009) first described this process, naming it the General Law of Double Development.

Nonetheless, there remained a gap in understanding the mechanism through which the brain of the new-born human baby first comes to establish the relational link which transforms the brain into an instrument of consciousness.

Proceeding from John S. Watson’s research on young babies’ “Contingency Analysis” of responses to its own acts (1967), Leal (1975/2004) studied this fixed action pattern. She called it an innate pattern of searching for a contingent response to one’s own action — a biological mechanism present from the child’s first days of life, to be understood as a turning point for the development of the human psyche (1975/2004, 1993, 2005, 2010).

Her lengthy studies resulted in a theory of “Genetic Affectology” (Leal, 1997, 2005, 2010), a description of the sequential socialization processes driving the construction of the human mind, and opening up an understanding of a distinct sociohistorical form of relational exchange between humans. In short, innate biological mechanisms are mediated by a responding Other, and converted into social functions, allowing the birth of language structures and the appearance of regulatory functions of human behavior (Vygotsky & Luria, 1996). If this biological mechanism is disrupted, the invitation for a spontaneous attachment to the human infant is disturbed, as well as his natural affiliation to the species, and thus the development of conscious behavior.

In observing sequences of imitative behaviors, both Watson (1967) and Leal (1975/2004) noted that the initiator is the infant, not any external element; this results in a so-called “proto-conversation,” experienced by babies as pleasurable play, which confirms the baby’s agency (Leal, 2010, Quintino-Aires, 2016).

The next step is the exclusive responsibility of an Other for producing social behavior in the infant. It is the caretaker’s job to establish cognitive and emotional exchange based on biological mechanisms, thus allowing consciousness to emerge. A disruption of this relational format may be seen as causing those autistic disturbances described by the DSM and ICD.

Leal (1975/2004, 1982) and Quintino-Aires (2016) defend the possibility of later intervention in the process through adequate implementation of a model of exchange relationships, which involves mutually contingent responses that foster the development of personality and the structuring of higher nervous functions.

The clinical intervention model applied by the RLS rests on these premises, and introduces a therapeutic model based on the scientific research of Leal, Quintino-Aires, Vygotsky, Luria, and Leontiev.

Intervention

Intervention is based on training health and educational professionals and peers (children and adolescents with strong empathic capacities) to re-establish a mutually contingent format of interchange with ASD individuals (Leal, 1975/2004, 1993, 2005, 2010).

Intervention focuses three principal and interrelated dynamic axes:

- Axis 1: ASD individuals. Before integration into the RLS, each ASD individual is followed through two weekly sessions of psychotherapy and neuropsychological habilitation, with the purpose of getting to know their individual characteristics. The clinical team applies systemic psychotherapeutic techniques centered on motivation and mutual attention, which are understood to be necessary for seizing words as signifiers, a fundamental process for organizing ASD individuals’ behavior, and forming human relationships (Quintino-Aires, 2016);

- Axis 2: Parents. The heart of the method rests on scientific evidence that interaction between parents and their children with ASD plays an ever more important role in wide-spread habilitation (Bowen, 1993; Green et al., 2015). Consequently, they have an active role in the treatment process, the goal being to enable them to recognize and interpret their children’s attempts to communicate;

- Axis3: Peers.TheRLSprogramactivelyencouragestheintegrationofindividuals with ASD into heterogeneous groups of peers, and involves them in learning situations, thus putting into practice UNESCO’s basic principles of human rights (UNESCO, 1994; ONU, 2006).

The RLS program takes place weekly in the presence of a supervisor, two primary school teachers, two psychologists, one social worker, nine peers and three ASD individuals. Every session is filmed, so as to be able to be used as material for analysis. Also, at the end of each session, the team members record themselves discussing their experience in that session.

A second supervisor is responsible for the group’s clinical review of the videos. The continuous supervision is intended to optimize the attentive quality of professionals and peers, and encourages mediation processes between participants.

Clinical supervision and training

Audio-visual support is the main methodological feature of clinical supervision, and allows videotaped interventions to be subsequently discussed by supervisors and the technical team. This analysis allows discussion of the mediational activity of each professional (Clot, 2006, 2010).

All work begins with intensive training in the general techniques for establishing relationships with ASD individuals, and handing over the initiative for contingent exchange to them, since the aim should be to improve the professional’s relational availability. Therefore, this relational attitude only becomes effective when:

- Mutually Contingent Exchange establishes a relational pattern (Leal, 1975/2004, 2003, 2010);

- Empathic understanding exists, consisting in the professional taking in the autist’s Eigenwelt (inner world), absorbing his or her subjective representations (Quintino-Aires, 2016);

- Naming and the Narrative emerge, leading to a constant description of events and training the “scenario” of accepting the roles that arise (Leal, 1975/2004, 2015; Quintino-Aires, 2016).

In addition to these general attitudes, professionals must never forget specific historical-cultural techniques. These techniques, when used to respond to the communication needs of the ASD individual, increase the possibility of appropriating their culture:

- Repetition increases verbal production with communicational value (Leal, 2003, 2015; Quintino-Aires, 2016);

- Emotional echo, consisting in naming the emotions/feelings transmitted or described by the subject without being conscious of them, thus helping the child apprehend feelings in respect to things, people, and/or events (Leal, 2003, 2015; Quintino-Aires, 2016);

- Generalization is used to reduce the child’s anxiety by conveying that a certain experience is typical of the human condition (Leal, 2003; Quintino-Aires, 2016).

Pedro Ferreira Alves, mentor and supervisor of the RLS, has been developing a list of orientations for supplementing these techniques, centered on attaining quality in the dialogic relationship between the professionals and the autistic child:

- Training attention and focus: obtained through promotion of eye contact and the habit of saying the autistics’ child name in the course of interactions; this creates involvement with the activities/reality;

- Transmitting a sense of security: a comforting touch or presence has a synchronic character, both physical and emotional (Winnicott, 1951, 1965; Leal, 2005);

- Relational support: this promotes mutual attention and the ability of the individual to be an integral part of the group;

- Verbal/emotional expression: signaling verbally to, and resonating emotionally with, the autist’s concrete reality, thus translating this reality for them.

- Everyday situations: promoting psychological development, stressing a sense of security and resourcefulness to get acquainted with day-to-day problems. (Gudeman & Craine, 1976; Trexler, 2012);

- Concrete descriptions or questions: it is necessary to describe or to ask questions in an accessible way to the ASD individual, since abstract, vague ones, or those containing simultaneous instructions, are not assimilable. The relational process mediated by the techniques listed above allows the construction of a plan of intervention in accordance with the subject’s ZPD.

Method

Goals of research

We try to understand the relationship between intervention techniques, the relational involvement of each professional and peer, and the development of social skills and motivation for learning by ASD individuals. So, in analyzing two of the ASD individuals of RLS (both ten year olds), the specific goals are:

- demonstrating that supervision has the effect of de-centering the professionals, meaning that the team is more aware of each autists’ individual characteristics, and therefore more available for the autists’ needs;

- demonstrating that the evolution of the relational quality contributes to promoting cooperative learning.

Research procedure

The research counted on audiovisual resources to register the field work. “The Observer XT 12” software (Noldus, 2014) was used to analyze observational records, classifying them according to previously specified codes that permit the construction of nuclei of signification (Aguiar, Soares & Machado, 2015).

Two groups of data were analyzed:

- The professional’s team verbal and non-verbal discourse recorded at the end of each session;

- The observed relational dynamics, which demonstrate the interaction and motivational quality of the intercourse between the professionals, peers, and ASD individuals in the recorded learning situation.

Analysis of verbal and non-verbal discourse of the professional team. 108 individual interviews were analyzed. Each team member was asked to describe his/ her daily experience in the project. The verbalization of the experiences produced three principal nuclei of signification. A total of 38 discriminators were defined, organized in the categories described in Table 1.

Table 1. Analysis of Verbal and Non-verbal Discourse Discriminators

|

Category |

N |

|

Self-appraisal |

10 |

|

Hetero-evaluation |

11 |

|

Description of ASD individuals: dialogic relationship cooperative learning |

17 12 5 |

The first nucleus identifies different reactions when one is pondering one’s own action. The second indicates the view of the group’s actions by the participants. The third nucleus focuses on descriptions of each autist, divided into two categories: the dialogic relationship and cooperative learning. To see a full description of each discriminator, refer to Appendix A[1].

The length of discourse and frequencies of each discriminator were identified.

Analysis of the relational and motivational quality of a learning situation. This analysis was made from choosing video recordings which contained instances of cooperation in a basic academic concepts learning situation, specifically reading, in which at least two ASD individuals were present. After analyzing these recordings, a moment of cooperative success in reading was identified, as this was the concrete goal of the RLS. The 52 discriminators which were defined were divided into 5 categories, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Behavioral Analysis Discriminators

|

Category |

N |

|

Motor reflexes |

15 |

|

Verbal reflexes |

8 |

|

Relational behavior |

10 |

|

Techniques |

13 |

|

Emotions/feelings |

6 |

Motor reflexes focus on all the motor actions taken by ASD individuals, peers and professionals. Verbal responses indicate behaviors with communicational content. Relational behaviors describe behaviors intended to establish relationships. So-called techniques include all actions by psychologists, teachers, and competent peers with the explicit aim of incentivizing the formation of relationships and learning. The category emotions/feelings points out the emotional resonance observed in the ASD individuals. To see a full description of each discriminator, refer to Appendix B[2].

Frequencies of distinct behaviors were identified, thus bringing out instances of success in the observed sequences.

Results

Verbal and non-verbal discourse of the professional team

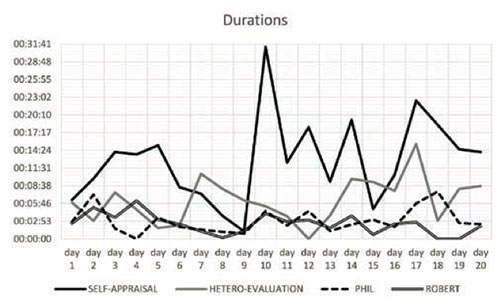

Global considerations. In Figure 1, one may see the total length of discourse of each nucleus of signification. The blue line indicates self-appraisal, while the red line registers hetero-evaluation, these being more salient than other categories. It should be noted that on days 10, 11, 16 and 17 there was no supervision of the RLS activities. In the supervisors’ absence, professionals and peers became more centered on private preoccupations, feeling the difficulties of the project more intensely, while expressing the need for supervision.

Figure 1. Length of discourse of each category of verbal and non-verbal analysis

Self-appraisal. In Table 3, one may distinguish “Liked” as the most frequent discriminator (f=307), followed by “Insecurity” (f=205), indicating that the team is constructing a differentiated picture of the difficulties in establishing a relationship with someone with ASD — i.e., constructing realistic involvement. Note that on the days when supervisors were absent, “Insecurity” rose drastically, and then decreased with their return. This process is underscored when you consider other discriminators such as “Tiredness,” “Need for Supervision,” and “Negative Expectations.” This shows the importance of continuous supervision, which, by making the creation of the relationship more conscious, improves the intervention.

As for “Achievement,” the highest value occurs on the first day that supervisors were absent, but decreases abruptly on the next day, as if the team was wanting to prove its competence, only to encounter difficulties in maintaining a contingent relationship with the autists. That is probably why “Activity Structured in Supervision” was more common on the first day of the supervisor’s absence, as if there were an augmented need to have the guidelines of previous supervision.

As the team gains self-consciousness, each participant may construct a more encompassing understanding of the other, thus attaining greater efficiency in the habilitation of the ASD individual. The aim is to obtain an ever more empathic, i. e., de-centered, team.

For the extended table, refer to Appendix C[3].

Table 3. Discriminator frequencies of the self-appraisal category (abbreviated table)

|

DAY |

… |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

… |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

… |

f |

|

LIKED (+) |

(…) |

4 |

16 |

9 |

15 |

(…) |

7 |

11 |

9 |

12 |

(…) |

307 |

|

INSECURITY |

4 |

35 |

13 |

6 |

3 |

11 |

7 |

1 |

205 |

|||

|

ACHIEVEMENT (+) |

0 |

20 |

9 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

110 |

|||

|

TIREDNESS |

3 |

9 |

9 |

5 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

89 |

|||

|

SUPERVISION need |

2 |

11 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

79 |

|||

|

ACHIEVEMENT (-) |

0 |

9 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

55 |

|||

|

EXPECTATION (-) |

1 |

7 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

31 |

|||

|

SUPERVISION activity structured |

0 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

22 |

Hetero-evaluation. Looking at Table 4, we see that the themes of positive “Success” (f=248), and positive “Confidence” (f=96) stand out, followed by negative “Organization” (f=95). Again, the need for organization and supervision is underlined in the discourse, revealing the team’s preoccupation with the functioning of the group. Note the increase in negative indicators found in discourse on the occasion of the supervisors’ absences. Negative values for “Organization” increase strikingly, and decrease to zero with the return of supervisors. The same is observed when considering negative “Confidence” and “Expectation.” This negative evaluation shows the group’s high level of commitment to finding access to the world of each ASD individual. The days in which “Activity Structured in Supervision” was more prominent were those when supervisors were absent. This suggests that interpolating supervision with its occasional absence causes an increase in the team’s effort to become aware of the objectives elaborated during supervision.

For the extended table, refer to Appendix D[4].

Table 4. Discriminator frequencies of the hetero-evaluation category (abbreviated table)

|

DAY |

… |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

… |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

… |

f |

|

SUCCESS (+) |

(…) |

6 |

17 |

4 |

15 |

(…) |

2 |

8 |

7 |

10 |

(…) |

248 |

|

CONFIDENCE (+) |

4 |

10 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

96 |

|||

|

ORGANIZATION (-) |

0 |

16 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

8 |

29 |

0 |

95 |

|||

|

SUPERVISION need |

0 |

8 |

5 |

5 |

1 |

6 |

12 |

1 |

71 |

|||

|

SUPERVISION activity structured |

2 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

7 |

12 |

7 |

64 |

|||

|

SUCCESS (-) |

0 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

28 |

|||

|

CONFIDENCE (-) |

0 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

0 |

23 |

|||

|

EXPECTATION (-) |

0 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

Description of each ASD individual

Robert

Dialogic Relationship. It is clear that Robert’s stance is very emotional (as presented in Table 5), and shows his urgent need for a dialogic relationship, a need which is revealed by his key actions (Elkhonin, 1998) being identified as “Play” (f=34) and “Initiative” (f=17). “Peer interaction” appears more often than “Interaction with professionals,” but “Cooperation” and “Displeasure” are expressed verbally, which is a good indicator of mental health. The frequency of references to “Play,” “Initiative,” and “Cooperation” attests to therapeutic effectiveness.

Table 5. Discriminator frequencies of the children’s description category — Robert, dialogic relationship

|

Dialogic relationship |

|

F |

|

PLAYING |

Positive |

34 |

|

DISPLEASURE |

Verbal |

27 |

|

INITIATIVE with speech |

Positive |

17 |

|

INTERACTION |

positive, peers |

16 |

|

COOPERATION |

Positive |

15 |

|

INTERACTION |

positive, professionals |

13 |

|

VERBAL COMMUNICATION |

positive, daily concepts |

12 |

|

INTERACTION |

negative, peers |

11 |

|

INTERACTION |

negative, professionals |

11 |

|

JOY |

8 |

|

|

PLEASURE |

Positive |

7 |

|

TOUCH |

Positive |

5 |

|

INITIATIVE with speech |

Negative |

4 |

|

PLAYTIME |

Negative |

3 |

|

TOUCH |

Negative |

2 |

Dialogic relationship. Playing Positive 34 Displeasure Verbal 27 Initiative with speech Positive 17 Interaction positive, peers 16 Cooperation Positive 15 Interaction positive, professionals 13 Verbal communication positive, daily concepts 12 Interaction negative, peers 11 Interaction negative, professionals 11 Joy 8 Pleasure Positive 7 Touch Positive 5 Initiative with speech Negative 4 Playtime Negative 3 Touch Negative 2

Table 6. Discriminator’s frequencies of the children’s description category – Robert, cooperative learning

|

Cooperative learning |

|

f |

|

LEARN |

positive, basic academic concepts |

35 |

|

TASK SUPPORT |

positive, professionals |

15 |

|

RULES |

Negative |

14 |

|

RULES |

Positive |

10 |

|

ATTENTION |

Positive |

10 |

|

TASK SUPPORT |

negative, professionals |

6 |

|

TASK SUPPORT |

positive, peers |

6 |

|

ATTENTION |

Negative |

4 |

|

LEARN |

negative, basic academic concepts |

3 |

|

LEARN |

positive, daily concepts |

3 |

|

TEACH |

positive, basic academic concepts |

3 |

|

TASK SUPPORT |

negative, peers |

1 |

|

TEACH |

positive, daily concepts |

1 |

Cooperative learning. Learn positive, basic academic concepts 35 Task support positive, professionals 15 Rules negative 14 Rules positive 10 Attention positive 10 Task support negative, professionals 6 Task support positive, peers 6 Attention negative 4 Learn negative, basic academic concepts 3 Learn positive, daily concepts 3 Teach positive, basic academic concepts 3 Task support negative, peers 1 Teach positive, daily concepts 1

Cooperative Learning. As can be observed in Table 6, Robert is very open to learning basic academic concepts. He is the child whose indicators show greater consistency; thus he demonstrates a huge potential for learning, and ease in asking for help when he’s experiencing difficulty.

The fact that “Playtime” was identified as a main activity at an early stage simplified the implementation of a dialogic matrix for the learning process. It is important to highlight that after joining the RLS, Robert started getting positive grades in Mathematics.

Dialogic Relationship. In Table 7 one may identify the key activities (Elkhonin, 1998) which Phil developed; “Interaction with Peers,” “Play,” and “Initiative” in the relationship stand out. Note that Phil, being the most severe case, managed to present moments of “Initiative,” “Cooperation,” and “Touch.” Regarding Phil’s availability for “Interaction with Peers,” he showed a remarkable evolution. His greater availability to relate to peers was very apparent. This underlines the importance of having heterogeneous groups in social and school situations which include ASD individuals, as this is a determinant factor in the development of the autist’s social capabilities.

Table 7. Discriminator frequencies of the children’s description category – Phil, dialogic relationship

|

Dialogic relationship |

|

F |

|

|

INTERACTION |

positive, peers |

25 |

|

|

PLAYING |

Positive |

24 |

|

|

NO ENERGY |

22 |

||

|

PLEASURE |

17 |

||

|

INTERACTION |

positive, professionals |

14 |

|

|

INITIATIVE |

positive |

13 |

|

|

COOPERATION |

positive |

13 |

|

|

COMUNICATE VERBALLY |

negative, daily concepts |

12 |

|

|

TOUCH |

Positive |

11 |

|

|

JOY |

11 |

||

|

DISPLEASURE |

9 |

||

|

VERBAL COMMUNICATION |

positive, daily concepts |

2 |

|

|

INTERACTION |

negative, professionals |

2 |

|

|

VISUAL CONTACT |

Negative |

2 |

|

|

INITIATIVE |

Negative |

1 |

|

|

INTERACTION |

negative, peers |

1 |

|

Cooperative learning. In Table 8 the team concretely identifies Phil’s ZPD. Phil is open to acquisition of basic academic concepts, even if he needs the help of peers and professionals to hold his attentive actions in place, and organize his perceptions.

Early on, it was noted in practice that the autist’s availability to be involved in learning situations was increased when mediation included competent peers as protagonists.

Table 8. Discriminator’s frequencies of the children’s description category – Phil, cooperative learning

|

Cooperative learning |

|

f |

|

LEARN |

positive, basic academic concepts |

31 |

|

ATTENTION |

Negative |

22 |

|

TASK SUPPORT |

positive with professionals |

20 |

|

ATTENTION |

Positive |

10 |

|

TASK SUPPORT |

positive with peers |

9 |

|

RULES |

Positive |

9 |

|

TASK SUPPORT |

negative with professionals |

8 |

|

RULES |

Negative |

7 |

|

LEARN |

negative, basic academic concepts |

5 |

|

LEARN |

positive, daily concepts |

4 |

|

LEARN |

negative, daily concepts |

2 |

Analysis of the relational and motivational quality of a learning situation

Instances of learning situations. As child development proceeds through external mediators such as toys, drawing, and constructions — as introduced in play therapy — tasks of neuropsychological development are launched, and respond to the child’s growing curiosity. These tasks open space for the child to structure rudiments of grammar and math, familiarize himself with the nature and phenomena of social life, train coordinated movements, and learn other skills. In all cases, the initiative comes from the child; then regulating guidelines are introduced.

In the first week of the RLS an interesting development produced the following scenario. Robert, a child with ASD, took the initiative of starting to read, and showed enormous pleasure in this. In supervision it was suggested that the book could be constituted as an external mediator to promote the group’s interest in reading. In the second week, Robert took the initiative of starting to read, and the professionals encouraged peers to involve Phil in the activity. The results of the analysis will be presented below.

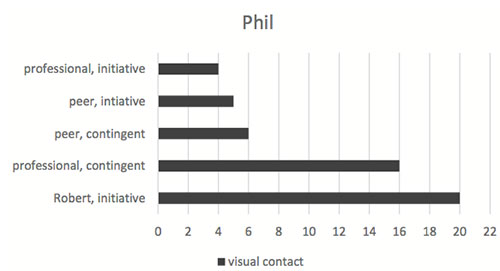

Training the dialogic relationship. The graph shows Phil’s visual contacts during motivational moments in the course of one day at the RLS. One may observe that he clearly prefers making visual contact with Robert, his peer. He also displays contingent behavior in respect to other peers and therapists, though in lesser quantity.

Figure 2. Phil’s visual contacts

Motivation for reading. It is clear that Phil prefers being near his peers. His initiatives and intentions are generally directed to Robert or other peers, preferably in the same age group. In respect to therapists, he may be contingent, but does not show initiative.

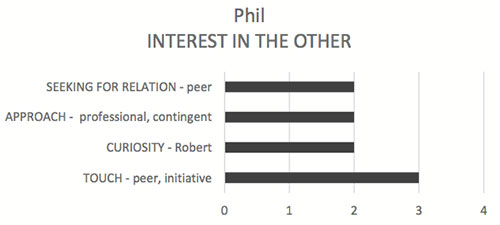

To make it possible for Phil to develop closeness and common interests when approaching his peers, it was necessary for the group to experience Robert’s curiosity for reading during the first week, and to wait for him to be motivated to share his interest with Phil. This moment of cooperation during reading emerged at Robert’s initiative, enabling Phil to develop this interest in reading, as is shown in the following graph (Figure 4).

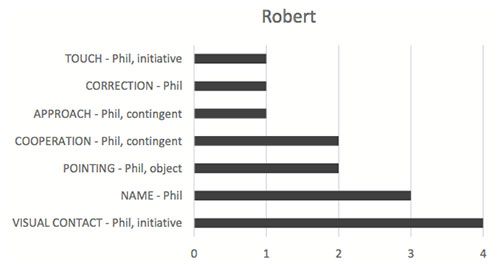

You may observe that visual contact occurs most often when Robert takes the initiative in relation to Phil. He both says his name and points with his finger when prompting Phil in reading, or correcting him. This relational dynamic culminates in the moments of contingent cooperation between both.

Figure 3. Phil’s interest in the other

Figure 4. Robert’s interaction with Phil

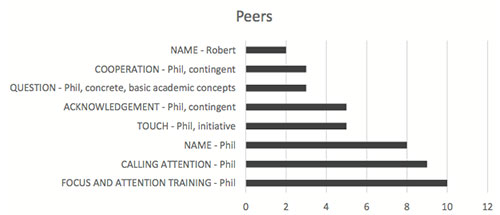

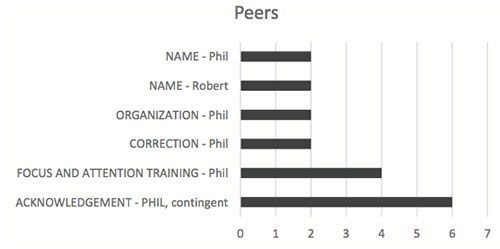

Relation mediated by peers. Because we are referring to a dialogic process, such instances depend on the team’s training. The graph below (Figure 5) brings out the techniques the professionals used most, and those used by peers who are sufficiently mature and highly empathic.

The principal techniques are focus and attention training on a specific activity, including saying the autist’s name, and sometimes including touch. Positive feedback in respect to performance is equally important, which is produced by contingent acknowledgment.

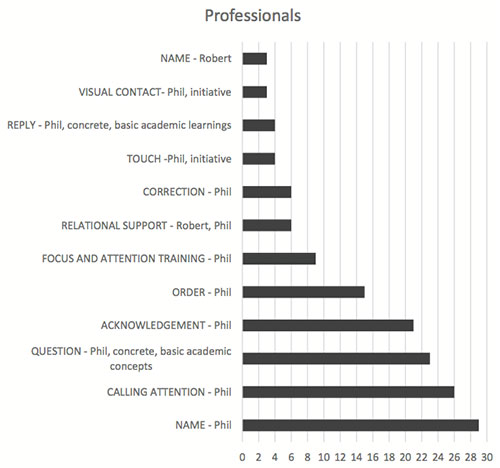

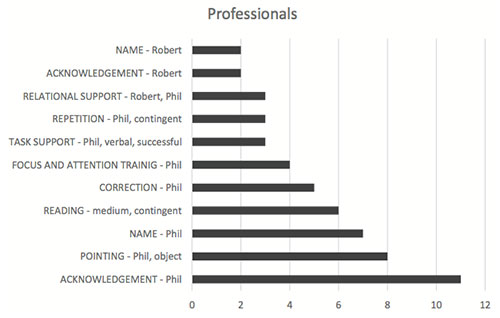

Relation mediated by professionals. Professionals are responsible for creating the conditions to allow Phil, Robert, and their peers to experience instances of cooperation.

As can be seen in Figure 6, professionals often repeat the act of naming, as well as of calling attention, and setting forth concrete questions which sustain moments of learning, when they are combined with correction and focusing attention on the activity. They also confirm the children’s actions and orient the organizing of activities. Relational support is equally important, since it allows the creation of opportunities for cooperative learning.

Figure 5. Peer’s interaction with Phil and Robert

Figure 6. Professionals’ interaction with Phil and Robert

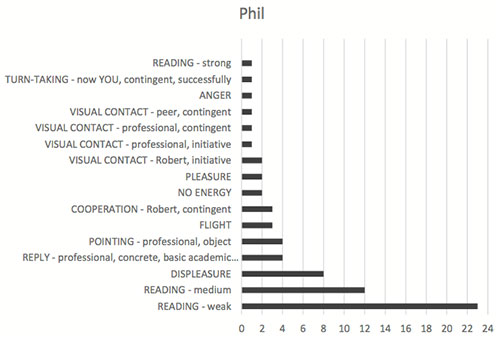

Phil’s reading. The next graph (Figure 7) shows reading activity occurring often, weak reading being the most common. In time, space can be found for more consistent reading, leading to success in involving Phil in the activity, as demonstrated by the frequency of situations in which reading increases to a medium tone, and in some moments, to a strong tone. Initiatives of visual contact coming from Phil start appearing. Nonetheless, such activities are very tiring for Phil, who expresses displeasure, anger, and escape behavior, calling attention to his ZPD.

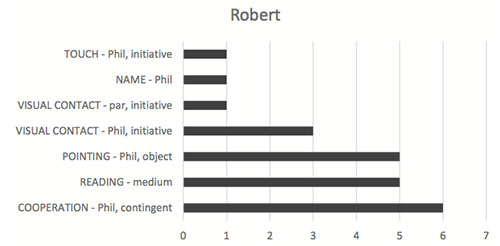

Cooperation. It is Robert’s help which aids Phil in perfecting his reading. He often cooperates, pointing with his finger at the book, showing his intention to help. One can observe (Figure 8) that there were many initiatives by Robert to establish visual contact with Phil. His example of good reading also motivates Phil to read. As the weeks have gone by, Robert has become a competent peer for Phil.

Figure 7. Phil while reading

Figure 8. Robert’s cooperation with Phil

Peers while reading. The next graph (Figure 9) describes Phil’s and Robert’s relationships with peers in those instances where reading is occurring. Peers had an important role in motivating both of them. This is brought out when looking at data for confirmation (acknowledgment), focus and attention training, naming Phil and Robert, and the initiative of upholding Phil’s acts of reading.

Figure 9. Peer’s actions with the intent of creating the cooperative learning moment

Figure 10. Professionals’ actions with intent of creating the cooperative learning moment

Professionals’ action while reading. As shown in Figure 10, success is observed those 11 times when the child’s reading activity is confirmed. This rested on techniques of focusing attention through pointing with the finger and saying the name. Relational support between the two is to be noted.

Conclusion

The present paper focuses on specific behaviors intended to identify barriers to be overcome in working with ASD individuals, thus concentrating on the description of the RLS model of intervention. It focuses on two different aspects: the evolution of the team’s perception and involvement, and the analysis of a moment of cooperative learning.

Verbal and non-verbal discourse of the professional team

The analysis of the perspective of the professionals and peers at the end of each session underlines the importance of clinical supervision. The results indicate that this activity permits a reflexive attitude toward the set of procedures, and the attitudes which are learned and built in the course of personal, academic, and professional development. This allows continual and constant renovation, amplifying the possibilities for action (Clot, 2006). The construction of consciousness about one’s role in the process of humanization of an individual with ASD must be an effective preoccupation during treatment. The dialectic of rehearsal and reformulation of the intervention during supervision allows a scrupulous, and not just spontaneous, work in the task of learning to recongnize and interpret the communicational attempts of an individual with ASD.

The reflection and systematic training of the team permit involvement in, and a conscious rehearsal of, each incidence of decision and hesitation; this makes each intervention a gradually more attentive rehearsal of the relational quality with which one should encounter each individual with ASD.

The relational and motivational quality of intercourse in the learning situation

We believe that learning to read is dependent on contingent responses to the subjects’ initiatives, and on adequate levels of mediation, preferably with peers, because they function as figures to identify with in a more spontaneous manner. Reading is an example of the incidence of the importance of social exchange, and, in this case, it makes it possible to compare the efforts of two ASD individuals with different levels of severity of the problem.

The disparity between each member of the group, coupled with the construction of a bond between them, enables the exchange necessary for the autist’s acquisition of new concepts and skills, and creates conditions for increasingly independent resolution of problems. In this cooperation, more mature peers provide and lend various tools and goals with which children with ASD get familiar, and then gradually appropriate.

In the excerpt analyzed above, it was observed that double mediation was more efficient than single. Double mediation takes place when the supervisor or other professionals orient competent peers, so that they are the principal figures mediating the autist’s learning. Within the playful spontaneity typical of child’s play and rehearsal of juvenile relationships, the peers were oriented to integrating themselves in dialogue with the autist, with the result being a unique sharing moment.

Limitations

On-site video recordings, analyzed with a demanding Software Program (Noldus, 2014), have produced a great profusion of data to be further explored in a subsequent paper. In the meantime, one must recognize that the small sample of ASD individuals studied should limit the possibility of generalizing any conclusions.

References

Aguiar, W. M. J. de, Soares, J. R., & Machado, V. C. (2015). Núcleos de significação: Uma proposta histórico-dialética de apreensão das significações [Nuclei of signification: A historical-dialectical proposal of apprehension of meanings]. Cadernos de Pesquisa [Research Proceedings], 45(155), 56-75. doi: 10.1590/198053142818

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. doi:10.1108/rr-10-20130256

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. doi:10.1176/ ajp.137.12.1630

Artigas-Pallarés, J., & Paula, I. (2012). Autism 70 years after Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger. Revista de la Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría, 32, 567-587. doi:10.4321/s021157352012000300008

Asperger, H. (1991). Autistic psychopathy in childhood. In U. Frith (Ed.), Autism and Asperger syndrome (pp. 37–92). London: Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1944). doi:10.1017/CBO9780511526770

Bleuler, E. (2005). Dementia Praecox ou Grupo das Esquizofrenias [Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias] (J. N. Almeida & M. Sommer, trans.). Lisboa, Portugal: Climepsi editores. (Original work published 1911).

Bowen, M. (1993). Family therapy in clinical practice. New York: J. Aronson : Distributed by Scribner Book Companies. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct= true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=482101

Clot, Y. (2006). A função psicológica do trabalho [The psychological function of work]. Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro: Vozes.

Clot, Y. (2010). Trabalho e poder de agir [Work and power to act ]. Belo Horizonte: Fabrefactum.

Elkhonin, D. B. (1998). Psicologia do jogo [Psychology of play]. São Paulo: Martins Fontes.

Fontes, A., Freixo, O., & Victória, C. (2004). Vygotsky e a aprendizagem cooperativa: Uma forma de aprender melhor [Vygotsky and the cooperative learning: A way to learn better]. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte.

Green, J., Charman, T., Pickles, A., Wan, M. W., Elsabbagh, M., Slonims, V., … Johnson, M. H. (2015). Parent-mediated intervention versus no intervention for infants at high risk of autism: a parallel, single-blind, randomized trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(2), 133–140. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00091-1

Goldson, E. (2016). Advances in Autism — 2016. Advances in Pediatrics, 63(1), 333-355. doi:10.1016/j.yapd.2016.04.014

Gudeman, H. E., & Craine, J. F. (1976). Principles and techniques of neurotraining. Hawaii State Hospital: Privately published manuscript. Kanner, L. (1943). Affective disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217-250.

Kanner, L. (1959). The Syndrome of infantile autism. In S. Arieti (ed.), American Handbook of Psychiatry. New York: Basic Books.

Leal, M. R. M. (2004). Introdução ao estudo dos processos de socialização precoce na criança [Introduction to the study of the processes of socialization in early child]. São Paulo: IPAF Editora. (Original work published 1975).

Leal, M. R. M. (1982). Uma proposta alternativa para tratamento de crianças com perturbações de contacto [An alternative proposal for the treatment of children with contact disturbances]. Revista Portuguesa de Psicologia [Portugal Journal of Psychology], 19, 157-178.

Leal, M. R. M. (1993). Psychotherapy as mutually contingent intercourse. Porto: APPORT. Leal, M. R. M. (1997). O processo da hominização [The hominization process]. Lisboa: ESEIMU.

Leal, M. R. M. (2003). A psicoterapia como aprendizagem: Um processo dinâmico de transformações [Psychotherapy as learning: A dynamic process of transformations]. Lisboa: Fim de Século.

Leal, M. R. M. (2005). Finding the other finding the self. São Paulo: IPAF. ISBN

Leal, M. R. M. (2010). Passos na Construção do Eu - Step by Step Constructing a Self. Lisboa: Fim de Século Edições.

Leal, M. R. M. (2015). Brincar o Munto: Habilitação e Reabilitação [Playing the world: habilitation and rehabilitation]. Lisboa: Oficina Didáctica.

Leontiev, A. (1978) O desenvolvimento do psiquismo [The development of the psyche]. Lisboa: Horizonte Universitário. (Original work published 1972).

Mukhina, V. (2006). Psicologia da Idade Pré-Escolar [Psychology of the pre-school age]. São Paulo: Martins

Fontes. Noldus. (2014). The observer XT reference manual: version 12 [computer software]. Wageningen: Noldus Information Technology.

Quintino-Aires, J. M. (2001). Contingent Analysis as a Paradigm of the Human Relationships. Jornal de Psicologia Clínica, 2(1), 7-9.

Quitino-Aires, J. M. (2014). Contribution to postnonclassical psychopathology. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 7(3), 35-49. doi: 10.11621/pir.2014.0304

Quintino-Aires, J. M. (2016). Vigotsky-Luria na psicologia clínica no século XXI [Vygotsky and Luria in the clinical psychology of the 21st century]. In De las neurociencias a la neuropsicología - El estudio del cerebro humano [From neuroscience to neuropsychology - the study of the human brain] (1st ed.). (Vol.1, pp. 301-385). Barranquilla, Colombia: Ediciones Corporación Universitaria Reformada.

Robbins, D. (2001). Vygotsky’s psychology-philosophy: A metaphor for language theory and learning. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1293-6

Trexler, L. E. (2012). Cognitive rehabilitation conceptualization and intervention. Boston, MA: Springer US. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4250-2

UN General Assembly (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities, A/RES/61/106, Annex I. Retrieved from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4680cd212.html UNESCO (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Paris: Author.

Vygotsky, L. S. (2004). Sobre os sistema psicológicos [On psychological systems]. In Teoria e método em psicologia [Theory and method of psychology]. (pp. 103-135). São Paulo: Martins Fontes. (Original work published 1930).

Vygotsky, L. S. (2009). A construção do pensamento e da linguagem [The construction of thought and language] (2nd ed.). São Paulo: Martins Fontes. (Original work published 1934).

Vygotsky, L. S., & Luria, A. R. (1996). Estudos sobre a historia do comportamento: o macaco, o primitivo e a criança [Studies about the history of behavior: the monkey, the primitive and the child]. Porto Alegre: Artes Medicas.

Watson, J. S. (1967). Memory and “contingency analysis” in infant learning. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly of Behavior and Development, 13(1), 55–76.

Winnicott, D. W. (1951). Transitional objects and transitional phenomena. In Through Paediatrics to Psycho-analysis. London: Hogarth Press.

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. In Through Paediatrics to Psycho-analysis. London: Hogarth Press.

1. Appendix A.

Table 1. Discriminators of the category of self-appraisal

|

|

|

The interlocutor refers to... |

|

achievement

|

Negative |

not having been able to do something. |

|

Positive |

having been able to do something. |

|

|

supervision |

activity structured in |

his own role in an activity structured during supervision. |

|

need of |

having felt the need of supervision, either by saying it or by demonstrating insecurity. |

|

|

orientation by supervisor |

having received instructions from the supervisor. |

|

|

orientation by therapist |

having received instructions from another team member. |

|

|

Technique |

a technique applied by himself that was learned during supervision. |

|

|

tiredness |

- |

feeling tired or shows signs of tiredness. |

|

fear |

- |

feeling fear or shows signs of fear. |

|

surprise |

Negative |

a situation or characteristic which was a bad surprise. |

|

Positive |

a situation or characteristic which was a good surprise. |

|

|

joy |

- |

feeling joy or shows signs of joy. |

|

insecurity |

- |

feeling unsure or shows signs of insecurity. |

|

liked |

Negative |

not having liked a specific situation. |

|

Positive |

having liked a specific situation. |

|

|

expectation |

Negative |

a situation or characteristic which disappointed previous expectations. |

|

Positive |

a situation or characteristic which surpassed previous expectations. |

|

|

sadness |

- |

feeling sad or shows signs of sadness. |

Table 2. Discriminators of the category of hetero-evaluation

|

|

|

The interlocutor refers to... |

|

organization |

Negative |

an activity or situation considered badly organized by the team. |

|

Positive |

an activity or situation considered well organized by the team. |

|

|

conflict |

- |

a conflict between members of the team. |

|

disappointment |

- |

feeling disappointed about a specific situation or person. |

|

confidence |

negative |

lack of confidence in the team. |

|

positive |

confidence in the team. |

|

|

success |

negative |

lack of success in the realization of something by the team. |

|

positive |

success in the realization of something by the team. |

|

|

supervision |

activity structured in |

an activity done by the team that was structured during supervision. |

|

need of |

having felt the need of supervision of the team. |

|

|

orientation by supervisor |

another team member having received instructions from the supervisor. |

|

|

orientation by therapist |

another team member having received instructions from another team member. |

|

|

technique |

another team member using a technique learned during supervision. |

|

|

expectation |

negative |

a situation or characteristic which disappointed previous expectations of the team. |

|

positive |

a situation or characteristic which surpassed previous expectations of the team. |

Table 3. Discriminators of the category of ASD individuals’ description

|

Dialogic relation |

The interlocutor refers to an ASD individual... |

|

|

displeasure |

- |

having shown signs of displeasure, anxiety, sadness or anger. |

|

pleasure |

positive |

having shown signs of pleasure. |

|

initiative |

negative |

not having taken initiative. |

|

positive |

having taken initiative. |

|

|

verbal communication |

negative |

having communicated verbally in a way inadequate to the context. |

|

positive |

having communicated verbally in a way adequate to the context. |

|

|

playing |

negative |

having been aggressive or having disrespected another person or the rules established while playing. |

|

positive |

having successfully played with someone else. |

|

|

interaction |

negative; peers |

having had a bad interaction with a peer/peers. |

|

negative; therapists |

having had a bad interaction with a therapist/therapists. |

|

|

positive; peers |

having had a good interaction with a peer/peers. |

|

|

positive; therapists |

having had a good interaction with a therapist/therapists. |

|

|

cooperation |

negative |

not having cooperated with somebody. |

|

positive |

having cooperated with somebody. |

|

|

touch |

negative |

having rejected touch or being aggressive to somebody. |

|

positive |

having touched someone in order to establish relations with somebody. |

|

|

visual contact |

negative |

not having tried to, or being unable to, establish visual contact with somebody. |

|

positive |

having tried to, or being able to, establish visual contact with somebody. |

|

|

fear |

- |

having shown signs of fear. |

|

joy |

- |

having shown signs of joy. |

|

no energy |

- |

not having had energy for establishing relations. |

|

Cooperative learning |

|

|

|

task support |

negative; peers |

not having been able to support a peer/peers in a task. |

|

negative; therapists |

not having been able to support a therapist/therapists in a task. |

|

|

positive; peers |

having been able to support a peer/peers in a task. |

|

|

positive; therapists |

having been able to support a therapist/therapists in a task. |

|

|

learn |

negative; basic academic concepts |

not having been able to learn basic academic concepts. |

|

negative; daily concepts |

not having been able to learn daily concepts. |

|

|

positive; basic academic concepts |

having been able to learn basic academic concepts. |

|

|

positive; daily concepts |

having been able to learn daily concepts. |

|

|

teach |

positive; basic academic concepts |

having taught basic academic concepts to somebody else. |

|

positive; daily concepts |

having taught daily concepts to somebody else. |

|

|

rules |

negative |

not having followed the established rules. |

|

positive |

having followed the established rules. |

|

|

attention |

negative |

not having paid attention. |

|

positive |

having paid attention. |

|

2.Appendix B

Discriminators of behavioral analysis

Table 1. Discriminators of the category of motor reflexes

|

|

The action’s agent... |

|

attention |

has his attention focused on somebody or a specific task. |

|

approach |

approaches somebody or something. |

|

aggression against others |

has aggressive behavior towards somebody. |

|

kiss |

gives somebody a kiss. |

|

yawn |

yawns. |

|

hug |

hugs somebody. |

|

babbling |

emits a sound without a verbal meaning. |

|

transitional object |

has repetitive behavior with an object. |

|

handling |

handles an object. |

|

playing alone |

plays alone. |

|

body |

explores somebody’s body. |

|

touch |

touches somebody. |

|

flight |

has flight behavior. |

|

visual contact |

seeks or establishes visual contact with somebody. |

|

pointing |

points at somebody or something. |

Table 2. Discriminators of the category of verbal reflexes

|

|

The action’s agent... |

|

acknowledgment |

gives positive feedback to an ASD individual. |

|

reading |

reads. |

|

name |

says the name of an ASD individual. |

|

calling attention |

calls somebody’s attention. |

|

order |

gives an order to somebody or the group. |

|

naming |

names or describes an object, person or situation. It can be concrete (accessible to the individual with autism) or abstract (not accessible to the individual with autism).

|

|

question |

poses a question. It can be concrete (accessible to the individual with autism) or abstract (not accessible to the individual with autism).

|

|

reply |

gives an answer. It can be concrete (accessible to the individual with autism) or abstract (not accessible to the individual with autism) |

Table 3. Discriminators of the category of relational behavior

|

|

The action’s agent... |

|

calming |

calms somebody. |

|

spontaneous contingency |

is spontaneously contingent. |

|

imitate |

imitates somebody. |

|

turn-taking |

passes the turn to somebody during an activity. |

|

requests for help |

asks for help. |

|

isolated |

is isolated. |

|

seeking for relation |

intentionally or unintentionally seeks a relationship with somebody. |

|

proposal for activity |

proposes an activity to somebody. |

|

cooperation |

cooperates with somebody. |

|

playful acts |

plays with somebody. |

Table 4. Discriminators of the category of techniques

|

|

The action’s agent... |

|

contingency |

is intentionally contingent with an ASD individual.

|

|

transmit security |

behaves in a supportive and cherishing way, both physically and emotionally transmitting the message “I am here for you”.

|

|

turn-taking (technique) |

passes the turn to a ASD individual during an activity aiming to create a dialogic relationship which is pleasurable for the ASD individual. The purpose is to recreate the pattern of action “now-I-now-you-now-I”.

|

|

ZPD correction |

corrects a mistake committed by an ASD individual.

|

|

ZPD task support |

supports the accomplishment of a specific task when it seems to be too hard for the ASD individual to accomplish on his/her own.

|

|

ZPD negotiation |

negotiates the terms of realization of a task with an ASD individual so that it is accomplished, even if the ASD individual perceives it as difficult or impossible to accomplish.

|

|

Eigenwelt |

takes on the Eigenwelt of an ASD individual.

|

|

organization |

organizes the group, or one of its members, in a specific task.

|

|

emotional echo |

names emotions and feelings transmitted or described by the ASD individual without being conscious of it. The goal is to obtain apprehension of feelings in respect to things, people and/or events.

|

|

relational support |

incentivizes an ASD individual to interact with one or more elements of the group or vice-versa. This may come as a direct order/request/invitation or as a subtle change in focus of the group in a way that includes a member who is isolated at the moment. This is intended to promote mutual attention, or the ability of the individual to be an integral part and cooperate with the group.

|

|

generalization |

conveys that a specific experience of the ASD individual is typical of the human condition, reducing anxiety in moments of distress.

|

|

repetition |

repeats a sound, word or phrase emitted by the ASD individual. Should be limited to that which has communicational value, so that the increase in verbal production may have an increasing communicational effect and may feed the dialogic relationship.

|

|

attention and focus training |

guides the ASD individual in a way it helps him remember constantly where his attention’s focus should be at a specific moment (e.g., pointing at something). |

Table 5. Discriminators of the category of emotion/feeling

|

|

Description |

|

insecurity |

Demonstration of insecurity. |

|

anxiety |

Demonstration of anxiety or impulsiveness. |

|

anger |

Demonstration of anger. |

|

pleasure |

Demonstration of pleasure, enthusiasm or joy. |

|

displeasure |

Demonstration of displeasure, tiredness, sadness, pain, fear or insecurity. |

|

curiosity |

Demonstration of curiosity or expectation. |

3. Appendix C.

Table 3 extended. Discriminator frequencies of the self-appraisal category (EXTENDED TABLE).

|

DAY |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

f |

|

LIKED (+) |

18 |

17 |

30 |

18 |

16 |

21 |

23 |

9 |

4 |

16 |

9 |

15 |

8 |

33 |

7 |

11 |

9 |

12 |

21 |

10 |

307 |

|

INSECURITY |

16 |

15 |

18 |

12 |

14 |

11 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

35 |

13 |

6 |

6 |

8 |

3 |

11 |

7 |

1 |

7 |

10 |

205 |

|

ACHIEVEMENT (+) |

4 |

16 |

12 |

5 |

6 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

20 |

9 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

5 |

110 |

|

TIREDNESS |

6 |

8 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

9 |

9 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

6 |

4 |

89 |

|

SUPERVISION need |

13 |

9 |

6 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

11 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

79 |

|

JOY |

4 |

4 |

10 |

5 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

61 |

|

ACHIEVEMENT (-) |

2 |

4 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

55 |

|

EXPECTATION (+) |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

8 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

3 |

46 |

|

EXPECTATION (-) |

6 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

31 |

|

LIKED (-) |

1 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

30 |

|

Structured Activity SUPERVISION |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

22 |

|

FEAR |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

|

SADNESS |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

12 |

|

f |

74 |

85 |

94 |

60 |

60 |

54 |

49 |

30 |

14 |

127 |

53 |

40 |

30 |

71 |

22 |

44 |

40 |

19 |

50 |

44 |

4. Appendix D.

Table 4 extended. Discriminator frequencies of the hetero-evaluation category (EXTENDED TABLE).

|

DAY |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

f |

|

SUCCESS (+) |

3 |

8 |

22 |

16 |

15 |

9 |

26 |

11 |

6 |

17 |

4 |

15 |

4 |

15 |

2 |

8 |

7 |

10 |

26 |

24 |

248 |

|

CONFIDENCE (+) |

1 |

4 |

13 |

8 |

6 |

4 |

14 |

5 |

4 |

10 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

96 |

|

ORGANIZATION (-) |

5 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

16 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

8 |

29 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

95 |

|

ORGANIZATION (+) |

2 |

3 |

14 |

9 |

6 |

3 |

11 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

85 |

|

SUPERVISION need |

9 |

4 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

8 |

5 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

12 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

71 |

|

SUPERVISION activity structured |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

12 |

7 |

7 |

5 |

64 |

|

SUCCESS (-) |

3 |

2 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

28 |

|

EXPECTATION (+) |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

28 |

|

CONFIDENCE (-) |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

23 |

|

DISAPPOINTMENT |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

|

EXPECTATION (-) |

1 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

|

f |

25 |

35 |

70 |

42 |

31 |

21 |

66 |

25 |

17 |

80 |

28 |

35 |

14 |

37 |

13 |

39 |

77 |

27 |

49 |

37 |

To cite this article: Rodrigues T. F., Alves P. U. M., Tirone C., Prade D. (2016). A new perspective on autism: Rita Leal School. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 9(4), 163-192.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.