Supporting Vulnerable Groups of Students in Educational Settings: University Initiatives and Partnerships

Abstract

Background. During the last decades, the need for supporting vulnerable groups of the population facing crisis situations and adversities has grown dramatically. School communities have been particularly affected increasing the need for interventions promoting individual and system’s resilience and well-being.

Objective. This paper presents an integrated approach to linking theory, training, research, and interventions in the Greek educational system in an alternative model for providing school psychological services. This approach puts particular emphasis on the development, implementation, and evaluation of evidence-based prevention and intervention programs for enhancing resilience and supporting school communities during unsettling times.

Results. In particular the programs that have been developed and implemented by the Laboratory of School Psychology (LSP), National and Kapodistrian University of Athens are reviewed and presented. For the evaluation of the evidence-based intervention programs, a multilevel assessment model has been applied. Overall, results showed the effectiveness of SEL-based intervention programs aiming at a) enhancing individual resilience and psychological adjustment; and b) supporting school communities during adversities, such as economic recession, refugee influx, and natural disasters.

Conclusion. The evaluation process and the positive outcomes of the programs highlight the critical importance of implementing intervention programs to support all members of school communities. The description of the various actions developed and implemented by the LSP stresses the important role that universities can play in bridging the gap between theory, research, training, and practice in the field of school psychology.

Received: 27.08.2019

Accepted: 10.10.2019

Themes: Educational psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2019_4/Psychology_4_2019_65-78_Hatzichristou.pdf

Pages: 65-78

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2019.0404

Keywords: vulnerable groups; university partnerships; evidence-based programs; SEL intervention programs; economic recession; refugee influx; Greek educational system

Introduction

Despite the advances in mental health service delivery in the Greek educational system during the last decades, the provision of school psychological services in mainstream public schools is still limited (Hatzichristou, Polychroni, & Georgouleas, 2007; Hatzichristou & Polychroni, 2014). In addition, the need for support of vulnerable groups of the population due to crisis situations, such as the economic recession, refugee influx, and natural disasters, has grown. Vulnerability is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2002) as “the degree to which a population, individual or organization is unable to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impacts of disasters (p. 5).” Furthermore, vulnerability is linked with the risk for developing psychopathology and susceptibility to undesirable outcomes (Wright, et al., 2013). Resilience, on the other hand – also defined asinvulnerability – refers to the ability of individuals and systems to overcome life’s adversities (Masten, 2016; Satici, 2016).

During recent years, an on-going period of economic recession has occurred that had significant impact for the greater part of the population in Greece leading to high unemployment rates and to the departure of a high number of educated people to other countries (Hatzichristou, Lianos, & Lampropoulou, 2017). This situation has escalated with the unprecedented inflow of refugees. According to UNHCR's Greek annex (www.unhcr.org/gr), over the last five years (2014 – June 2019) there have been almost 1,200,000 arrivals by land and sea in Greece alone. Furthermore, in the summer of 2018, a wildfire burned extensive populated regions in the coastal areas of Eastern Attica, claiming the lives of 102 people, some of them children and adolescents. This situation made a large impact on the school community as well (Hatzichristou, 2019a).

These events can be considered stressful or even traumatic, being potentially capable of causing physical or emotional pain, depending on how a person experiences or responds to such an event (Rossen & Cowan, 2013). The internal and external effects of the individual's experience can be impacted by the values and cultural beliefs of a group, available social support, and individual predispositions (Chafouleas, Johnson, Overstreet, & Santos, 2015). In addition, the characteristics of the event can influence the experience, including prediction, duration, consequences, and intensity (Brock & Jimerson, 2013). The occurrence of such events within school communities can affect a large number of people. Supporting the members of affected school communities, especially the vulnerable and at-risk groups, is an important part of a school psychologist’s role and requires special training, knowledge, and skills (Hatzichristou, 2019a).

Throughout the past two decades, the Laboratory of School Psychology (LSP) (former Center for Research and Practice of School Psychology) of the Department of Psychology at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, has developed, implemented, and evaluated several programs for supporting school communities and promoting resilience, well-being, and psychosocial adjustment of vulnerable students in multiple educational settings. These interventions also included training and consultation of teachers, school administrators, parents, and psychologists (Hatzichristou & Lianos, 2016). The Laboratory’s scientific team consists of the Scientific Director, experienced school psychologists, and PhD candidates who coordinate and supervise the intervention teams (school psychologists, PhD candidates, graduate and undergraduate students, teachers, and other volunteers). In this paper the conceptual framework guiding the LSP’s approach for linking theory, training, research and interventions in the Greek educational system at the context of an alternative model of school psychological services provision for vulnerable groups of students is discussed. Subsequently the interventions and programs implemented at a school and system level are presented.

Provision of Alternative School Psychological Services

The limited provision of school psychological services in Greek mainstream public schools has led to the development of an alternative model for providing school psychological services, which connects theory, research, training, and practice over four interrelated phases. The first three phases provide the empirical data which set the basis for the fourth phase, which is the development and implementation of several activities by the LSP scientific team. The first three phases are evolving and constantly enriched by several new research domains that provide new areas of intervention (Hatzichristou, 2011).

Conceptual Framework

One of the basic activities of the LSP is the development and application of intervention programs which are assessed through an evidence-based approach (Hatzichristou, 2014; Hatzichristou, Adamopoulou, & Lampropoulou, 2014; Hatzichristou, Lykitsakou, Lampropoulou, & Dimitropoulou, 2010). These programs have followed the guidelines of a constantly evolving conceptual framework that combines current trends, new theoretical concepts, empirical studies, and data at a national and international level. The result of this multi-year effort is a proposed synthetic model for developing interventions for promoting resilience and well-being (see Hatzichristou, Lampropoulou, & Lianos, accepted for publication, for description).

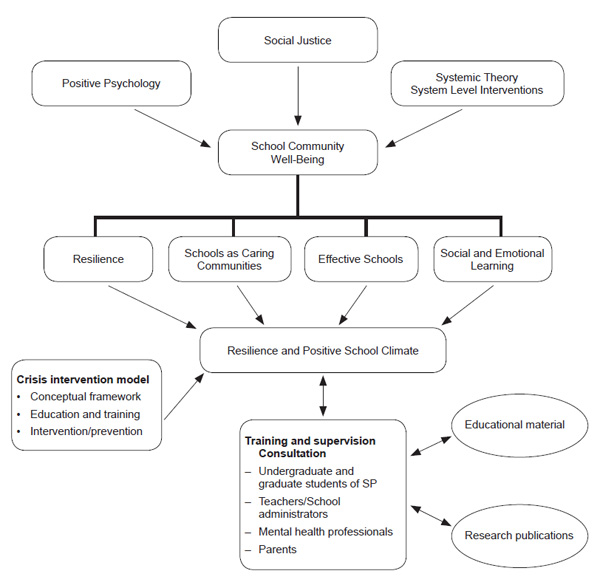

This synthetic model includes an approach to school community well-being within the framework of the basic principles of social justice and children’s rights. The model, apart from the systemic approach, and the emphasis on positive psychology, also incorporates current trends, the latest theoretical approaches,and practice models from the literature on resilience, effective schools, schools as caring communities, and social-emotional learning(Hatzichristou, 2014; Hatzichristou et al., under review). By integrating these theoretical components into system-level interventions, schools can enhance resilience and promote a positive school climate(see Figure 1).

This synthetic model was further enriched by the development of a multi-level model for crisis preparedness and intervention that includes multi-layered, multi-dimensional, and multi-faceted approaches which take into consideration contextual factors and cross-cultural and cross-national perspectives (Hatzichristou, Issari, Lampropoulou, Lykitsakou, & Dimitropoulou, 2011). In relation to crisis prevention and intervention special emphasis is given on multi-level resilience promotion (individual, classroom and school level). Resilience has always been a core concept of the intervention’s conceptual framework and one of the main outcome targets. However, it was further stressed in the face of the adversities in Greece. Consequently, a common foundation for all the interventions implemented over the last decade was the enhancement of individual and system resilience at either a primary level (enhancing the skills for all children and supporting teachers for future challenges), or a secondary level (helping children and the teachers deal with the existing adversities in Greece).

These efforts comprise a resilience approach consisting of four basic domains: Building, Empowering,Supporting,and Training (Hatzichristou, 2019a). Building resilience includes interventions that primarily aim to help individuals and systems develop resilience and resilient characteristics that will be of use in their everyday lives and in times of future adversities. The second domain (Empowering) includes interventions that empowerand support individuals and systems when an adverse event has already occurred.Supportingresilience is a supplementary domain for the above interventions, and requires the cooperation and the involvement of all members of the school community via consultation and support whenever it is needed. Finally,trainingin resilience is a constantly required domain that should aim to prepare all members of a school community to efficiently promote resilience before, during, and after a crisis.

Figure 1. Multi-level conceptual framework for promoting resilience and positive climate in school communities, through SEL-based interventions for vulnerable groups of students.

Programs for Supporting Vulnerable Groups of Students in School Communities

Programs for social-emotional learning (SEL) are considered an important dimension of mental health intervention in the school setting. They promote acquisition and effective application of emotional understanding and management, the setting of positive goals, empathy expression, developing positive relationships, and responsible decision-making (CASEL, 2013). Social and emotional skills are the basis for enhancing resilience at both an individual and system level. SEL-based programs focused on promoting resilience are especially beneficial for supporting schools after crisis situations.

Recently, emphasis has been placed on developing trauma-informed practices (Mendelson, Tandon, O’Brennan, Leaf, & Ialongo, 2015). A key element of an effective trauma-informed school is the provision of clear guidelines to all school community members regarding how to identify behaviors that may be reactions to traumatic events, and to whom to refer children and families when additional services are essential. Trauma-informed schools can contribute to improved academic achievement and school climate, a reduction in students’ behavioral out-bursts, a reduction of stress for staff and students, lower levels of bullying behavior, and a reduction in dropouts (Walkley & Cox, 2013).

Supporting School Communities during Economic Recession

Responding to the needs of the school communities following the economic recession, a multilevel prevention, awareness-building, education, and intervention project aimed at creating a national and international school network of resilient schools, was developed (Hatzichristou et al., 2014). The project consisted of three school-based intervention programs: a) the Supporting in Crisis program; b) the Ε.Μ.Ε.Ι.Σ(Ενδιαφερόμαστε(Care) - Μοιραζόμαστε(Share) - Ενθαρρύνουμε(Encourage) – Ισχυροποιούμαστε(Empower) – Συμμετέχουμε(Participate) program; and c) the International Program WeC.A.R.E: Teachers’ training and intervention for the promotion of a positive school climate and resilience in the school community.

The Supporting in Crisis program was implemented during the peak of the economic crisis in Greece, and aimed to support and strengthen students’ and teachers’ resilience and well-being at an individual, group, and school community level. In total, 138 teachers, 29 schools, and almost 3000 students benefitted from the intervention. The structure of the program included specialized training seminars for teachers, classroom activities, and development of educational material. The multilevel evaluation model consisted of two phases: a) needs assessment, conducted at an individual and system level for teachers and students, focused upon the effects of the economic crisis as well as the school climate; and b) a pre- and post-assessment procedure with both qualitative and quantitative data from teachers and students, focused upon the program implementation, school climate, and psychological adjustment. Findings before and after implementation highlighted the program’s beneficial effects on students’ self-esteem and relationships (t[77] = -2.27; p<.05), initiative-taking, and school bonding (t [54] = -2.51; p<.05) (Hatzichristou et al., 2014).

The Ε.Μ.Ε.Ι.Σ. teachers’ training and intervention program for the promotion of resilience and a positive school climate in the school community was implemented the following school year, in order to address the intense needs for psychological support that emerged from the economic crisis. One hundred twenty-five teachers, 39 schools, and almost 3200 students were involved in the program.Its goals included: a) the development of a positive climate in the school environment; b) reinforcement of individual and group resilience; c) promotion of internal strengths, motivation, and skills for students and teachers; and d) enhancement of teachers’ professional skills. The program included teacher training seminars, classroom activities, supervision, and a closing ceremony. The multilevel evaluation model entailed: a) needs assessment, in terms of the effects of the economic crisis, and the classroom and school climate, conducted at an individual and system level for teachers and students; b) pre- and post-assessment by teachers and students, focusing upon the program implementation, and psychological adjustment at an individual and system level; and c) control group comparison. Analyses showed that higher levels of psychosocial adaptation (e.g., resilience, promotion of social skills, expression and management of stress and emotions, enhancement of self-esteem, improvement in learning, and goal setting), and positive school climate (i.e.,team spirit promotion, relationship improvement, increase in motivation levels, and reduction of conflict levels) were reported after the implementation of the program for both students and teachers. Vulnerable children (i.e., those experiencing intense economic difficulties and low achievers) were the ones who especially benefitted from the program (for a detailed description regarding assessment design and results,see Hatzichristou et al., 2014; Hatzichristou et al., 2017).

The International Program WeC.A.R.E. (We Connect, Accept, Respect, Empower) was implemented for five consecutive academic years (four phases) in schools from 13 countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, Ethiopia, Germany, Greece, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and the USA). It is a long-distance, web-based program for training teachers on classroom interventions that promote a positive climate and resilience in the school community. Through the use of distance learning, the program offered the opportunity for communication and exchange of experiences and knowledge among schools of different countries. Four hundred thirty-nine teachers, 287 schools, and 6,932 students participated in total. Teachers and their students cooperated online with other schools from Greece and abroad, via the “Sailing4Caring” online interactive educational platform that hosted the program’s modules and activities.

The evaluation of the program entailed a needs assessment phase, initial evaluation, process evaluation (at the end of each module), and post-assessment. A significant improvement in the dimensions concerning class climate and school relationships was indicated throughout the four phases. Teachers consistently reported higher levels in all dimensionsof a positive school climate, such as co-operation among students and increased frequencies of students showing respect and support. Likewise, students reported improvement in their ability to identify and express their feelings, in their social skills, and in their interpersonal relationships (for a detailed description, see Hatzichristou et al., 2014; Hatzichristou & Lianos, 2016).

Multilevel Approach for the Psychosocial Support of Vulnerable Groups of Students

There is growing international scientific interest in approaches and intervention programs that focus on the ability of school communities to cope with the learning and psychosocial needs of students exposed to traumatic experiences (Tyrer & Fazel, 2014; Wille, 2016). The following terms have been adopted to describe the approaches by schools to raise awareness of, information on, and intervention on student needs: “trauma-informed schools,” “trauma-sensitive schools,” and “trauma-responsive education.” (Cowan, Vaillancourt, Rossen, & Pollitt., 2013; Walkley & Cox, 2013; Wille, 2016).

Based on the above, the multilevel prevention and intervention model for crisis intervention has evolved to respond to the specific needs of vulnerable students, especially refugee children residing in refugee facilities. Over the past two decades, the LSP has developed, implemented, and evaluated several programs for the promotion of resilience, well-being, and psychosocial adjustment of students with migrant and refugee backgrounds in both general and multicultural schools, including teacher and parent training and consultation (Hatzichristou & Lianos, 2016). The principal goals of the model are: a) raising awareness concerning multicultural diversity; b) providing training, in order to empower all members of the community; c) implementing interventions; d) developing and allocating educational material and booklets; and e) building partnerships between University and school communities, institutions (i.e., schools, community centers, educational support centers, etc.), and networks of schools. Specific actions have ranged from sensitization of undergraduate and graduate students, and training graduate students in School Psychology in school interventions, to specialized training, consultation, supervision, and program implementation of teachers and mental health professionals at national and international levels.

Supporting Refugee Children and Adolescents in Educational Settings

A one-day workshop entitled “Psychosocial support for refugee children” was conducted for school professionals working with refugee children (i.e.,teachers, administrators, psychologists, social workers, NGO personnel, etc.) and undergraduate/graduate students, at the School of Philosophy of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens by members of the Laboratory of School Psychology team. Several invited speakers addressed refugee students’ psychosocial adjustment, trauma-informed practices, and practitioners’ self-care. Furthermore, a booklet with helpful suggestions concerning the psychosocial adjustment of refugee children and adolescents was uploaded on the LSP’s website, as a resource for parents, educators, and mental health specialists working with refugees (Hatzichristou et al., 2018).

Based on the multilevelprevention and intervention model, a project on supporting adolescent students in an atypical Learning Center (LC) inside a refugee facility in the greater Athens area was developed by the LSP’s team in collaboration with the British Council and UNICEF. It aimed at facilitating creative learning, psychosocial adjustment, and a sense of safety among refugee adolescents. The LSP team’s input focused on the following key elements: a) development of the conceptual framework and the incorporation of key components based on psychological needs into the daily LC curriculum; b) the basic training of key stakeholders; c) design and implementation of an SEL-based trauma-specific intervention program; and d) evaluation of the LC’s operation and exploration of factors that could provide feedback for the adjustment of refugee adolescent students in the school context. The following factors related to difficulties concerning the promotion and achievement of resilience, were taken into consideration: a) students’ and stakeholders’ needs for a common means of communication during the educational process; b) adolescents’ past educational experience, both prior to their trauma (war, relocation) and in their current accommodation centers (with limited essentials); c) exposure to multiple traumatic experiences; d) basic developmental needs (identity shaping and psychosocial adjustment); and e) the uncertain reality deriving from the children’s current living conditions.

The conceptual framework of the project incorporated the current international trends in school psychology and was based on a multi-tiered holistic approach to promoting positive development, adjustment, and support for refugee children and adolescents in the school community in the context of trauma-informed practices. This program intended to foster social engagement/re-engagement and well-being in new learning environments by linking theory, research, and practice. The key components focused on social justice, children’s rights, and multicultural/acculturation guidelines, and were further enriched by basic school psychology approaches.

Furthermore, training workshops for the preparation of the LC members were carried out throughout the school year by the LSP team, focusing on the principal components of the program’s design -- education about trauma and self-care, goals and values, crisis management, resilience and trauma-informed practices, and de-escalation techniques. Notably, the training context was adjusted according to the educators’ feedback, and was rendered more appropriate for the emerging psycho-emotional needs of the students and the participants. A major objective of the training sessions was the infusion of the key conceptual framework elements into the teaching practice of the LC staff.

Six staff members participated in training workshops. The six participants were asked to assess the training workshops by answering a survey consisting of closed (Likert scale, 1=Strongly Disagree, to 4=Strongly Agree) and open-ended questions. The trainees reported that during the seminars participation and interaction were encouraged (M=3.33), the topics presented were applicable in educational practice (M=3), and that the cooperation of the coordinators was satisfactory (M=3.17). Aspects of the training that they liked included: a) the activities and the examples; b) the positive attitude of the trainers; c) the information provided; and d) the flexibility and adaptability of the trainers in terms of the agenda and the needs of the group. Furthermore, the importance of the delivery of resources and ideas for implementation in the classroom was highlighted, as well as the understanding of the needs of students in this fragile context, especially through case study analysis and the provision of strategies and guidance for educators. Finally, the participants indicated that the seminars provided a space for reflection on the psychological needs of the students, and helped create a better understanding of the meaning of resilience through the implementation of relevant activities.

One of the project’s elements was the design, development, and implementation of a psychosocial support program entitled Building Our Horizons,which aimed to foster adolescents’ positive skills and abilities; promote resilience and a sense of well-being among refugee youth; prevent escalation of trauma impact; respect and foster multicultural diversity; and promote community integration (embrace of effective acculturation strategies). The four basic modules of the program were designed for vulnerable children (especially refugees) that have experienced multiple adverse situations: a) goals, values, and relationships; b) self-regulation; c) problem-solving in difficult situations; and d) identifying evolution and future goals. Activity modules included in-class activities and broader goals to be disseminated in the educational curriculum. The set of activities was proposed and demonstrated to the LC facilitators and teachers during the training workshops, in order to enrich their lesson plans and teaching methodology.

Overall, the project was considered a challenging opportunity for all participants involved, in order to enhance all those protective factors that set the fundamental prerequisites for resilience at a system level (students, staff, etc.). Prioritizing safety, communication, cultural, and relational issues – along with flexibility in re-designing and decision-making in difficult/crisis situations – served as essential materials to build an educational setting that fosters children’s learning engagement and psychosocial adjustment. However, regarding the LC experience and the operation of reception facilities for refugee education in general, further systematic research is needed due to the complex and emerging psychological and learning needs of refugee students. The main focus should be their integration into national public education systems with the aid of information and communication technologies (Joynes & James, 2018; World Bank, 2016).

University – schools – community centers interconnection model: supporting school communities with migrant and refugee students.

During recent years, the LSP has collaborated with a community-based educational support center in the central region of Athens, in order to provide psychosocial support for two elementary schools with high percentages of migrant and refugee students. This initiative was based on a University – schools – community center interconnection model for supporting schools with migrant and refugee students. The goals of the program were: a) the promotion of resilience, psychosocial support, and multicultural understanding for all students (school-based services); b) the development of a trauma-informed school network that can support vulnerable and at-risk students; and c) the development of cooperation among the University, school settings and community-based educational support center.

The program was implemented with the collaboration of the Graduate Program of School Psychology and the LSP of the Department of Psychology, NKUoA, and was linked with several courses on prevention and intervention in the school community, psychoeducational interventions in school, and supervision. Graduate school psychology students cooperated with teachers at multiple levels during their internship in multicultural schools. University-based supervision was provided to graduate students by academic supervisors/experienced school psychologists aiming to empower them as novice school psychologists, and to ensure the best possible provision of school psychological services to participating schools in general, and to refugee children in particular.

In particular, graduate school psychology students were trained in the implementation of the Building Our Horizonsprogram (see above for details) in multicultural classrooms, which had been designated by the two schools’ administrators as most in need of support. School-based supervision was provided both by the teaching staff responsible for the students’ practice and by the supervising school psychologist in the support center. Teachers and students reported positive effects of the program’s implementation in several aspects of school life, such as peer relations, emotional expression, conflict resolution, and respect for diversity; likewise, the graduate students appreciated the unique opportunity in the course of their internship to work in a system-level school-wide program.

This model can set the basis for the development of intervention programs and support networks among schools with large numbers of immigrant/refugee students, with an emphasis on exchange of resources and best practices (Hatzichristou, 2019a).

Supporting the school community after a natural disaster.During the current school year, after the disastrous wildfire occurred in the Eastern Attica, the LSP team supported the affected schools by a) providing supervision of, and consultation with, the psychologists appointed to these schools by the Ministry of Education, and b) implementing an SEL-based prevention program, designed for the special needs of the community, based on the principles of trauma-sensitive schools.

This endeavor was the result of a synergy among the LSP, the Ministry of Education, the schools of Eastern Attica (eight preschool and eight elementary schools), the appointed psychologists, and several community agencies that were active in the area after the wildfires. This partnership was designed and implemented on multiple levels, such as in-service training; consultation/supervision; development of tools, resources, educational material, and booklets; collaboration with school administrators and community agencies; and evaluation. Moreover, an SEL-based trauma-specific program (Mazi+ENA [“Together + 1” Program of psychosocial support and promotion of resilience in the school community: Focusing on psycho-emotional needs of students after a natural disaster]) was designed by the LSP and implemented in the schools of Eastern Attica by the psychologists. The basic objectives entailed strengthening resilience and supporting all students in a period of recovery and adaptation after the fires in eastern Attica. Emphasis was placed on the students’ psychological needs following the experience of the natural disaster. Furthermore, the development of a collaboration and support network between the LSP and school communities in need for interventions on the psychosocial adaptation of pupils who had been exposed to traumatic experiences was promoted (Hatzichristou, 2019a).

Universities as Change Agents for School Communities

The outcome of the various actions developed and implemented by the LSP highlights the important role that universities can play in bridging the gap between theory, training, research, and practice in the field of school psychology regardless of cultural or contextual factors. In addition, they underline the basic role that university-based centers/laboratories can undertake in addressing the limitations in the provision of school psychological services. Provision of services can be further promoted by universities, schools, community agencies, and professional associations partnering and collaborating at local, national, and international levels.

First and foremost, universities are the main institutions with the responsibility for preparing future professionals in psychology and school psychology. Young professionals should gain the knowledge, skills, and competencies that will help them provide services and respond to the existing and emerging needs of communities. In their graduate courses in school psychology, universities should provide the appropriate modules and opportunities for bridging the gap between academic and practical domains through promotion of partnerships with all school community stakeholders.In addition, the focus on multicultural and cross-cultural issues, the enrichment of the academic context with current theoretical approaches and international literature, the collaboration among universities through exchange of resources, and the provision of lectures or seminars can contribute to providing profound professional development of novice school psychologists.The collaboration of university trainers, professionals, and students at national and cross-national levels is of critical importance to this end (Hatzichristou, 2019b).

The collaboration of faculty members can also promote cross-national approaches with the aim of meeting the needs of children, schools, and families. Exchanging ideas and practices among colleagues within university contexts, and providing consultation in fields of professional expertise can contribute to the development of university networks, which enrich best practices and develop the most effective interventions and action plans. The development of international partnerships and networks for sharing experiences and learning are imperative within a global social justice perspective. Learning from each other at a broader level, and enriching one’s knowledge of other cultural and educational settings,ensure that multicultural perspectives are included in practice and promote professional and personal growth. The LSP is actively involved in developing such partnerships (i.e.,collaboration with colleagues from other countries, collaboration within international associations, etc.) and is committed to promoting international collaboration based on social justice principles of equality,fairness, respect, and acceptance.

The multidimensional role of universities, in relation to both training and providing school psychology services, is especially important when they are serving vulnerable and at-risk groups. Universities should focus on: a) providing knowledge and skills to identify and support the vulnerable members of school communities; b) enhancing school psychologists’ competencies in supporting schools and communities and acting as advocates; c) developing and implementing best practices and trauma-informed interventions when dealing with traumatic events or crisis situations; d) taking initiatives to provide alternative ways of school psychological services in school communities facing adversities, and to respond to the emerging needs according to social, political, or contextual factors; e) developing resources and educational material for professionals and parents; and f) fostering community outreach through activities aiming at building awareness and collaboration among all members of the school community, especially in times of recession.

Conclusion

Training, research, and practice initiated by universities in order to provide services to vulnerable and at-risk groups should be a priority and a main goal of university institutions. Universities are in a key position to meet the mental health needs of school communities and provide school psychological services, especially in settings where no such services are available. Initiatives in developing collaboration and networks among stakeholders and institutions at a national and international level, along with ensuring the provision of a globalized approach in training, can contribute to the development of best practices at a transnational level.

References

Brock, S.E., & Jimerson, S.R. (Eds.). (2013). Best practices in school crisis prevention and intervention (2nd ed.). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

Chafouleas, S.M., Johnson, A.H., Overstreet, S., & Santos, N.M. (2015). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2013). CASEL guide: Effective social and emotional learning programs—Preschool and elementary school edition. Chicago, IL: Author.

Cowan, K.C., Vaillancourt, K., Rossen, E., & Pollitt, K. (2013). A framework for safe and successful schools[Brief]. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Retrieved from https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources/school-safety-and-crisis/a-framework-for-safe-and-successful-schools

Hatzichristou, C. (2011). Sholiki Psychologia [Handbook of school psychology]. Athens, Greece: Typothito.

Hatzichristou, C. (2014). Symvouleftiki sti sholiki koinotita [Counseling and consultation in the school community]. Athens, Greece: Typothito.

Hatzichristou, C. (2019a). Connecting University and school communities: A model for provision of school psychology services after natural disasters. In C. Hatzichristou (chair), Interventions promoting psychosocial adjustment of vulnerable students and positive school climate. Symposium presented at the 41st International School Psychology Association Conference, Basel, Switzerland.

Hatzichristou, C. (2019b). Training in School Psychology: Programs of studies and international considerations. Roundtable presented at the 41st International School Psychology Association Conference, Basel, Switzerland.

Hatzichristou, C. & Lianos, P.G. (2016). Social and emotional learning in the Greek educational system: An Ithaca journey. International Journal of Emotional Education (special issue), 8(2), 105-127. Retrieved from https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar//handle/123456789/14459

Hatzichristou, C. & Polychroni, F. (2014). The preparation of school psychologists in Greece, International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 2(3), 154-165. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2014.934633

Hatzichristou, C., Adamopoulou, E., & Lampropoulou, A. (2014). A multilevel approach of promoting resilience and positive school climate in the school community during unsettling times. In S. Prince-Embury & D.H. Saklofske (Eds.), Resilience interventions in diverse communities(pp. 299-325). New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0542-3_14

Hatzichristou, C., Issari, P., Lampropoulou, A., Lykitsakou, K., & Dimitropoulou, P. (2011). The development of a multi-level model for crisis prevention and intervention in the Greek educational system. School Psychology International, 32(5), 464-483. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034311402918

Hatzichristou, C., Lampropoulou, A. & Lianos, P.G. (accepted for publication). Social justice principles as a core concept in school psychology training, research and practice at a transnational level. InternationalPerspectives on Social Justice (special issue).

Hatzichristou, C., Lianos, P.G., & Lampropoulou, A. (2017). Cultural construction of promoting resilience and positive school climate during the economic crisis in Greek schools. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology,5(3), 192-206. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2016.1276816

Hatzichristou, C., Lykitsakou, K., Lampropoulou, A., & Dimitropoulou, P. (2010). Promoting the well-being of school communities: A systemic approach. In B. Doll, W. Phohl, & J. Yoon (Eds.), Handbook of prevention science(pp. 255-274). New York, NY: Routledge.

Hatzichristou, C., Polychroni, F., & Georgouleas, G. (2007). A description of school psychology in Greece. In S.R. Jimerson, T. Oakland, & P. Farrell (Eds.), The handbook of international school psychology(pp. 135–146). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976138.n14

Hatzichristou, C., Yfanti, Th., Lianos, P., Lampropoulou, A., Stasinou, V., Georgoulas, G., & Fragiadaki, D. (2018). Psychosocial support for children and adolescents after a natural disaster: Useful highlights for the psychosocial adjustment of children and adolescents after a fire (booklet). Athens: Laboratory of School Psychology, Department of Psychology, NKUoA. Uploaded at http://centerschoolpsych.psych.uoa.gr.

Joynes, C. & James, Z. (2018). An overview of ICT for education of refugees and IDPs. K4D Helpdesk Report. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

Masten, A.S. (2016). Resilience in developing systems: the promise of integrated approaches. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13,1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1147344

Mendelson, T., Tandon, S.D., O'Brennan, L., Leaf, P.J., & Ialongo, N.S. (2015). Moving prevention into schools: the impact of a trauma-informed school-based intervention. Journal of Adolescence, 43, 142-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.05.017

Rossen, E. & Cowan, K. (2013). The role of schools in supporting traumatized students. Principal’s Research Review, 8(6), 1-7.

Satici, S.A. (2016). Psychological vulnerability, resilience, and subjective well-being: The mediating role of hope. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 68-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.057

Tyrer, R.A. & Fazel, M. (2014). School and community-based interventions for refugee and asylum-seeking children: A systematic review. PLOS One, 9(2), e89359. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089359

Walkley, M. & Cox, T. (2013). Building trauma-informed schools and communities. Children & Schools, 35(2), 123–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdt007

Wille, A.M. (2016). Facilitating Success for Refugee Students and their Families. Communiqué,44(6), 35.

World Bank. (2016). ICT and the education of refugees: A stocktaking of innovative approaches in the MENA region: lessons of experience and guiding principles. New York: World Bank. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/25172/Lessons0of0exp0d0guiding0principles.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

World Health Organization. (2002). Environmental health in emergencies and disasters: a practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Wright, A.G.C., Krueger, R.F., Hobbs, M.J., Markon, K.E., Eaton, N.R., & Slade, T. (2013). The structure of psychopathology: Toward an expanded quantitative empirical model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 122(1), 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030133.

To cite this article: Hatzichristou, C., Lianos, P., Lampropoulou, A. (2019). Supporting Vulnerable Groups of Students in Educational Settings: University Initiatives and Partnerships. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 12(4), 65–78.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.