The reliability and validity of a Russian version of the Lesbian Internalized Homophobia Scale

Abstract

Background. Validated measures of sexual minority stress (Meyer, 2003), including that caused by experiences of discrimination directed toward gay, lesbian and bisexual (GLB) people, GLB-related stigma, and internalized homonegativity, are not readily available in Russia. Given the particular context of Russia with respect to GLB rights, it is to be expected that there would be cross-cultural variations in dimensions of minority stress, including internalized homo-negativity.

Objective. For the present study, we aimed to back and forward translate the commonly used Szymanski and Chung’s (2001) Lesbian Internalized Homonegativity Scale (LIHS), and explore its cross-language validity.

Design. Our design consisted of a completion of the adapted LIHS by a sample of 74 Russian lesbian-identified women; participants were asked about their age of coming out to self, friends, and family.

Results. Based upon an examination of construct validity and internal consistency, the results suggest support for a modified four-component, 24-item Russian version of the LIH (R-LIH).The components were: Connection with Lesbian Communities (9 items); Public Identification as a Lesbian (7); Public Visibility as a Lesbian (5); and Cultural Awareness of Lesbian Communities (3). From the original LIHS scale, Personal Feelings about Being a Lesbian, Moral and Religious Attitudes toward Lesbians, and Attitudes toward Other Lesbians failed to demonstrate cross-cultural validity.

Conclusion. The adapted R-LIH scale suggests there are some constructs of internalized homonegativity that are salient in both U.S. and Russian communities, however, there are others (i.e., Moral and Religious Attitudes, Attitudes Toward Other Lesbians) that may not be relevant in Russian lesbian communities. The implications for the use of the translated version are described.

Received: 29.03.2017

Accepted: 23.05.2017

Themes: Psychology of sexual and gender identity

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2017_2/psych_2_2017_1.pdf

Pages: 5-20

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2017.0201

Keywords: lesbian, measurement, Russia, internalized homo-negativity, internalized heterosexism, cross-cultural

Introduction

Internalized homophobia, sometimes referred to as internalized homo-negativity (IH), is one aspect of minority stress. It describes the internalization by sexual minorities of negative societal attitudes toward homosexuality such as sexual prejudice, as well as stereotypes and cultural assumptions of gay, lesbian, and bisexual (GLB) people (Szymanski & Chung, 2001; Meyer, 2003). The first use of the term was intended to capture heterosexuals’ fear and dread of being in close quarters with homosexuals, as well as homosexuals’ self-loathing (Weinberg, 1972). Given the prevalence of negative attitudes towards GLB people in many societies, including Russia (Anderson & Fetner, 2008; Pew Research Center, 2013), it has been suggested that GLB people experience some degree of IH throughout their lifetimes (Shidlo, 1994), and that simply living in heterosexist societies and communities renders the internalization of these societal negative attitudes as largely unavoidable (Russell & Bohan, 2006).

Internalized homo-negativity has been found to be inversely related to indices of psychological well-being of GLB individuals. For both gay men and lesbian women, internalized homophobia is associated with less self-disclosure to heterosexual friends and acquaintances, and lower levels of connection to the GLB community (Herek, Cogan, Gillis, & Glunt, 1997; Puckett, Levitt, Horne, & Hayes-Skelton, 2015). Those with higher IH also show significantly more depressive symptoms and higher levels of demoralization, as well as lower self-esteem than those with lower IH (Allen & Oleson, 1999; Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 2009; Szymanski & Chung, 2001). IH is associated with other negative health impacts; among sexual minority women, for example, IH is related to body shame and negative body image, and alcohol abuse (Amadio, 2006; Bayer, Robert-McComb, Clopton, & Reich, 2016; Watson, Grotewiel, Farrell, Marshik, & Schneider, 2015), as well as feelings of being threatened and guilt among sexual minorities (e.g., Moradi, van den Berg & Epting, 2009). In their meta-analysis of extant studies on the association between IH and psychological distress, Newcomb and Mustanski (2010) found that effect sizes for the relationship between IH and internalizing mental health problems such as anxiety and depression varied significantly, with most effects tending to be small to moderate. Such differences in the impact of IH on sexual minorities may be due to variations in experience that are influenced by social or cultural factors.

It also may be that the variation in effect sizes of the relationship between IH and mental health may be due to the wide variability of approaches to measuring IH. Szymanski and colleagues (Szymanski, Kashubeck-West, & Meyer, 2008a, 2008b) explored the psychometric properties of IH measures and found that only five IH instruments had adequate internal consistency and validity. Among these measures, they included the Lesbian Internalized Homophobia Scale (LIHS), which was the only IH measure for sexual minority women at the time of their review. This scale has been used widely with diverse North American samples of sexual minority women, and has been adapted for use with a sample of Italian women (Flebus & Montano, 2009), and an Australian sample (Morandini, Blaszczynski, Dar-Nimrod, & Ross, 2015). In addition, Nguyen, Poteat, Bandeen-Roche, German, and Hai (2016) developed a scale drawing on items from existing IH measures, including the LIH, and considered culturally relevant constructs for Vietnam. Within their sample of Vietnamese sexual minority women, two factors of self-stigma and sexual prejudice were identified, and were found to have good internal consistency and to be highly correlated (Nguyen et al., 2016).

Sexual minority women and men may differ in aspects and trajectories of their identity development (Szymanski & Chung, 2003). Thus, Szymanski and Chung (2003) argued that there should be separate assessments of Internalized Heterosexism for women and men, based on research which shows greater fluidity in women’s sexual orientation, in contrast to gay men; research also indicates that items on some of the extant scales (i.e., HIV-related items and items assessing the desire to stop being gay) may be less applicable for use in evaluating lesbian and bisexual women than gay men. Also, sexual minority women’s experiences may have been impacted by feminist movements, in addition to socio-political events, which may make it beneficial to use separate assessments for researching GLB women in comparison to men (Szymanski & Chung, 2003). In addition, from a feminist perspective, women’s experiences as double minorities (or triple, in the case of GLB women of color) are often linked to negative assumptions perpetuated by heterosexist views specific to the role and place of women in society (Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008).

Szymanski and Kashubeck-West (2008) offered two theoretical approaches to conceptualizing the construct of internalized heterosexism. According to feminist principles, heterosexism affects individuals by way of violence, rejection, invisibility, and discrimination, among other negative experiences. Similarly, the minority stress model posits that IH has negative effects on both a micro (i.e., self-concealment) and macro (i.e., harassment by others) level of psychosocial well-being of those in minority groups. The IH measures (i.e., Nungesser’s 1983 Homosexuality Attitudes Inventory, Martin and Dean’s 1987 Internalized Homophobia Scale) that were in existence when the LIH was created, were largely developed using participants who were predominantly white, educated, middle- to upper-class men, and were geared toward the measurement of IH in the male population only. This is a significant limitation when one is attempting to accurately gauge the internalized homo-negativity of lesbian and bisexual women, and assess the generalizability of the tests overall.

To address this deficit, Szymanski and Chung (2001) developed the Lesbian Internalized Homophobia Scale (LIHS), using a rational and theoretical approach to assessment development. The LIHS is a 52-item scale designed to measure: 1) the connection with the lesbian community; 2) public identification as lesbian; 3) personal feelings about being a lesbian; 4) moral and religious attitudes toward lesbianism; and 5) attitudes toward other lesbians (Szymanski, Kashubeck-West, & Meyer, 2008a). It is currently the most valid scale created to measure IH in lesbian and bisexual women. Internal reliability alpha coefficients range from .74 to .92, the inter-scale correlations range from .37 to .57, and the Cronbach alpha for the total scale score is reported at .94. Test–retesting after a two-week period yielded correlations from .75 to .93. Content and construct validity was established by using an expert panel of raters, as well as by measuring correlations with scales of loneliness, self-esteem, depression, social support, passing for straight, membership in a GLB group, and conflict over sexual orientation (Szymanski & Chung, 2001). The LIHS has also been adapted for use with bisexual women (Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008).

As in the case of other scales developed to measure IH, the sample group used to create the LIHS was largely white, middle- to upper-class, U.S.-based, and well-educated, with the exception of a group of Italian sexual minority women (Flebus & Montano, 2009), and the adapted scale developed for Vietnamese sexual minority women (Nguyen et al., 2016). Szymanski and colleagues (2008) called for more IH research among racial and ethnic minority groups and those with lower socio-economic status, as well as among international populations (Szymanski, Kashubeck-West, & Meyer, 2008b). Furthermore, since many of the recruitment efforts for research participants take place through GLB cultural events and organizations, research has primarily been conducted with those who are lesbian self-identified, are fairly comfortable with their disclosure about their sexual orientation, and have connections to the GLB community.

It is important to assess IH among individuals who might be more diverse with respect to identity, who may not be “out,” and who may live in contexts that diverge from the Western trajectory of increasing GLB rights (e.g., marriage, adoption, etc.)–such as countries where contemporary policies have limited the rights and freedom for GLB individuals to be in recognized same-sex relationships, or to be “out” about their sexual identities. In order to understand IH from the framework of minority stress, exploring cross-cultural variations in IH would be worthwhile.

Assessing the utility of the LIHS may be beneficial in countries with historically variable attitudes toward homosexuality, such as Russia (Anderson & Fetner, 2008; Levada Center, 2015; Pew Research Center, 2013). In their interviews with GLBT Russian individuals, Horne, Ovrebo, Levitt & Franeta (2009) found that the history of repressive Soviet treatment of GLB people continues to exert influence on the sense of safety and degree of outness in their participants. Prior to Joseph Stalin’s accession to the leadership of the U.S.S.R. Communist Party in 1922, there had been periods of tolerance of same-sex relations within Russian society. According to Karlinsky (1989), homosexuality was neither shunned nor uncommon in Russia during czarist rule (1547-1917). In addition, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 maintained codes that established same-sex sexuality between two consenting adults as permissible (Healey, 2002).

In stark contrast, the rise of Joseph Stalin, along with the passage and enforcement of Article 121 (which criminalized same-sex relations between men) in 1934, evoked a strong political movement to eradicate homosexuality (Essig, 1999). Although Russia removed Article 121 from its criminal code in 1993, there continues to be a negative stigma surrounding GLB identities that has been, at a minimum, maintained, and more than likely increased, under Vladimir Putin’s leadership, especially with the passage of the anti-propaganda ban on non-traditional sexual relationships in 2013 (Anderson & Fetner, 2008; Horne, Maroney, Zagryazhskaya, & Koven, 2017; Pew Research Center, 2013).

Over the past five years, following the anti-GLB propaganda bill and other repressive measures, including a ban on gay pride parades in Moscow until 2022, GLB people have had to determine how best to survive in this environment; for some, this has meant returning to the closet or choosing to leave Russia altogether. In the presence of much anti-GLB vitriol, it’s likely that internalized homo-negativity plays an important role in the mental health of Russian GLB women. Quantitative assessments of the relationship between Russian anti-GLB attitudes and policies are warranted; however, GLB measurement tools are lacking. Our project aimed to (1) develop a valid measure of lesbian internalized homophobia by assessing the reliability and validity of a Russian version of the LIHS scale. Not only did we plan to explore questions of measurement, we hoped to (2) determine cross-culturally relevant dimensions of lesbian internalized homo-negativity specific to Russia, by performing a confirmatory factor analysis in order to compare potential cross-cultural differences in the experience of internalization.

Method

Participants

Data were collected via questionnaires that 74 sexual minority women filled out in person following a lesbian rights seminar in Moscow, Russia. There were 84 women who attended; ten elected not to complete the questionnaires. No identifying information was collected; the participants therefore were anonymous. All measures were forward and back translated by a team of five English and Russian speakers who were also lesbian-identified. The mean age was 32.12 years. On average, participants came out to themselves at 19.82 years, to friends at 23.19 years, and to parents at 24.39 years. Most participants were in a relationship with a same-sex partner

(80.6 %), and had been in their relationship an average of 6.5 years. In terms of the degree of outness, it ranged from women reporting they were only “out” to a few people, to those who reported they were “out” to almost all friends and family (M = 1.45; Range = 1–3).

Measures

Demographic Information. The questionnaire included the participants’ age; education level (middle and higher); age of outness to self, friends, and parents; general outness; relationship status; and length of relationship.

Outness. Several questions were asked to assess outness: “At what age did you acknowledge same sex attraction (to yourself)?”, “At what age did you tell friends about your same-sex attraction?”, and “At what age did you tell your parents about your same-sex attractions?” Finally, participants were asked how “out” they were on a scale from 1 to 3: 1 = a few friends and family; 2 = almost all friends and family; and 3 = all friends and family.

The Lesbian Internalized Homophobia Scale (LIHS) is a 52-item measure that was developed using a rational/theoretical approach of test construction. It includes five subscales reflecting five dimensions of internalized homophobia: 1) connection with the lesbian community; 2) public identification as a lesbian; 3) personal feelings about being a lesbian; 4) moral and religious attitudes toward lesbianism; and 5) attitudes toward other lesbians (Szymanski & Chung, 2001). Each statement is rated on a 7-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Average total and subscale scores are used, and higher scores indicate a greater degree of internalized homophobia. The Cronbach’s alpha for the original LIHS total scale is .94, and internal consistencies for the subscale scores for this sample ranged from .60 to .87.

Statistical analyses

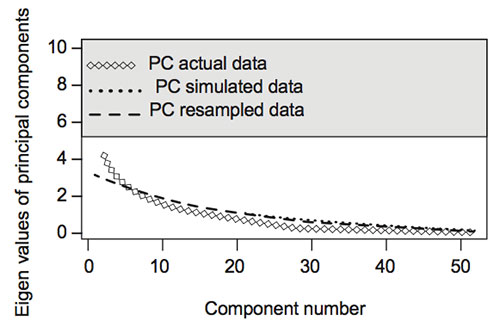

Analyses were conducted in the R statistical program (R Core Team, 2016), primarily utilizing the psych package (Revelle, 2016). The scale’s structure was established using a principal components analysis (Abdi & Williams, 2010). A scree test was utilized to determine the number of factors in which there were sharp breaks in the plot; such a test has been identified as a preferable choice in retaining factors, as compared to solely relying on eigen values (Osborne & Costello, 2009). A parallel analysis using ordinary least squares to find the minimum residual, was conducted to compare the observed data with random simulated analyses (Revelle, 2016). Reliability tests using Cronbach’s alpha were run on the new subscales, a method consistent with previous literature examining the use of the LIHS with a transnational sample (Nguyen et al., 2016). The new subscales were calculated by averaging item scores.

Results

Means and correlations between subscale totals, measured using Pearson’s method, are displayed in Table 1. Significant positive correlations were found between Age and Moral and Religious Attitudes toward Lesbianism (r = .37), and between the subscales Personal Feelings About Being a Lesbian and Connection With the Lesbian Community (r = .39). Significant negative relationships were found between questions exploring outness, such as “At what age did you tell your parents about your same-sex attraction?” and Connection with the Lesbian Community (r = –.36).

Results of the factor analysis showed that a five-factor model was the best fit for the data (RMSEA = .101, TLI = .673). Parallel analysis suggested that five factors be retained (See Figure 1). A total of 28 items were eliminated, as they did not meet the minimum criteria for having a primary factor loading of 0.5, which is considered to be a strong loading (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Items from the subscales of Attitudes toward Other Lesbians and Moral and Religious Attitudes toward Lesbianism from the U.S. LIHS were not retained, as they did not meet the minimum criteria.

An oblimin rotation provided the best defined factor structure, and resulted in the selection of 4 factors. These retained factors were based on the questions comprising each factor, primarily utilizing the names from the U.S. version of the LIHS (Szymanski & Chung, 2001), with the exception of Public Visibility as Lesbian, which was deemed qualitatively different in the Russian context, and thus different in factor loading. The four factors identified were Connection to the Lesbian Community (Items 1–3, 6–8, 45–48, 51); Public Identification as a Lesbian (Items 13, 15–22); Public Visibility as a Lesbian (Items 23, 26–29); and Lesbian Cultural Awareness (Items 9–10, 12).

Table 1.

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

M |

SD |

|

1 |

Age |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

— |

- |

- |

32.1 |

10.2 |

|

2 |

Age out |

.475** |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

19.8 |

7.0 |

|

3 |

Age out |

.500** |

.524** |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

21.4 |

9.2 |

|

4 |

Age out |

.156 |

.129 |

.338* |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

12.9 |

13.1 |

|

5 |

Outness |

.097 |

.050 |

.288* |

.531** |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3.2 |

1.2 |

|

6 |

CLC |

-.076 |

.024 |

.060 |

-.344** |

-.142 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3.4 |

.61 |

|

7 |

PIL |

.099 |

.144 |

.093 |

-.113 |

-.180 |

-.024 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4.2 |

.42 |

|

8 |

PFL |

.246 |

.247 |

.097 |

-.233 |

-.177 |

.246* |

.132 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4.5 |

.50 |

|

9 |

MRATL |

-.383** |

-.135 |

-.194 |

-.079 |

-.041 |

.125 |

.094 |

.148 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3.0 |

.55 |

|

10 |

ATOL |

-.120 |

.234 |

.125 |

-.038 |

.137 |

.076 |

.088 |

о Г |

.272* |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

4.1 |

.65 |

|

11 |

CLC_R |

-.202 |

-.083 |

.025 |

-.244 |

.021 |

.563** |

-.155 |

-.002 |

.157 |

.184 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3.5 |

.47 |

|

12 |

CLC_R |

.162 |

.011 |

.018 |

-.017 |

-.377** |

.017 |

.435 |

.315** |

.284* |

-.088 |

.075 |

- |

- |

- |

3.9 |

.57 |

|

13 |

PVL_R |

-.053 |

.207 |

.183 |

.145 |

.421** |

-.146 |

.448** |

-.203 |

-.147 |

.189 |

-.091 |

-.443** |

- |

- |

4.9 |

1.3 |

|

14 |

LCA_R |

-.219 |

-.039 |

.042 |

-.187 |

-.109 |

.755 |

.025 |

.104 |

.106 |

.081 |

.293* |

.007 |

-.132 |

- |

2.6 |

1.1 |

Table 2.

|

Item |

Russian Translation |

Factor-Loading |

Alpha |

|

Connection to Lesbian Community (CLC) |

|

|

.85 |

|

R-LIH1 (CLC) When

interacting with members of the lesbian |

Когда я общаюсь с лесбиянками, я часто чувствую |

.58 |

|

|

R-LIH2 (CLC) Attending lesbian events and

organizations is im- |

Посещение лесбийских мероприятий важно для |

.69 |

|

|

R-LIH3 (CLC) I feel

isolated and separate from other lesbians. |

Я чувствую себя отстраненной от других лесбиянок. |

.53 |

|

|

R-LIH4 (CLC) Being a part

of the lesbian community is impor- |

Для меня важно быть частью сообщества лесбиянок. |

.71 |

|

|

R-LIH 5 (CLC) Having

lesbian friends is important to me (re- |

Для меня важно иметь друзей лесбиянок. |

.67 |

|

|

R-LIH 6 (CLC) I feel comfortable joining a

lesbian social group, |

Я чувствую себя комфортно являясь частью |

.61 |

|

|

R-LIH 7 (CLC) I feel

comfortable with lesbian womens commu- |

я чувствую себя комфортно с женшинами- |

.58 |

|

|

R-LIH-8 (CLC) Lesbians

are too aggressive. (LIH Attitudes To- |

Лесбиянки слишком агрессивные. |

.52 |

|

|

R-LIH-9 (CLC). I have

respect and admiration for other lesbians |

я уважаю и могу восхищаться другим лесбиянками. |

.54 |

|

|

Public Identification as a Lesbian (PIL) |

|

|

|

|

R-LIH-10 (PIL) I try not

to show that I am a

lesbian.(LIH Public |

Я стараюсь не показывать, что я лесбиянка. |

.50 |

|

|

R-LIH-11 (PIL) fm

comfortable about being an 'out5 lesbian |

Я комфортно себя чувствую, как лесбиянка, я хочу, |

.53 |

|

|

R-LIH-12 (PIL) I wouldn’t

mind if my boss knew that I was a |

Я бы не возражала, если мой начальник узнал, что я |

.60 |

|

|

R-LIH-13 (PIL) Its

important to me to keep it a secret from my |

Для меня важно скрывать то, что я лесбиянка от |

.50 |

|

|

R-LIH-14 (PIL) I am not

worried about anyone finding out that |

Я не волнуюсь, что кто-нибудь узнает, что я |

.80 |

|

|

R-LIH-15 (PIL) I feel

comfortable talking about homosexuality in |

Я могу спокойно говорить о гомосексуальности в |

.54 |

|

|

R-LIH-16 (PIL) I don’t

feel the necessity to lie or conceal that I’m |

Я не чувствую необходимость врать и скрывать от |

.57 |

|

|

Public Visibility as a Lesbian (PVL) |

|

|

.85 |

|

R-LIH -17 (PVL) If my

acquaintances found out that I’m a les- |

Если бы мои знакомые узнали, что я лесбиянка, они |

.54 |

|

|

Public Identification as a Lesbian (PIL) |

|

.85 |

|

| R-LIH-10 (PIL) I try not to show that I am a lesbian.(LIH Public Identification as a Lesbian 1) |

Я стараюсь не показывать, что я лесбиянка. |

.50 |

|

|

R-LIH-11 (PIL) fm

comfortable about being an 'out5 lesbian |

Я комфортно себя чувствую, как лесбиянка, я хочу, |

.53 |

|

|

R-LIH-12 (PIL) I wouldn’t

mind if my boss knew that I was a |

Я бы не возражала, если мой начальник узнал, что я |

.60 |

|

|

R-LIH-13 (PIL) Its

important to me to keep it a secret from my |

Для меня важно скрывать то, что я лесбиянка от |

.50 |

|

|

R-LIH-14 (PIL) I am not

worried about anyone finding out that |

Я не волнуюсь, что кто-нибудь узнает, что я |

.80 |

|

|

R-LIH-15 (PIL) I feel

comfortable talking about homosexuality in |

Я могу спокойно говорить о гомосексуальности в |

.54 |

|

|

R-LIH-16 (PIL) I don’t

feel the necessity to lie or conceal that I’m |

Я не чувствую необходимость врать и скрывать от |

.57 |

|

|

Public Visibility as a Lesbian (PVL) |

|

|

.85 |

|

R-LIH -17 (PVL) If my

acquaintances found out that I’m a les- |

Если бы мои знакомые узнали, что я лесбиянка, они |

.54 |

|

|

R-LIH -18 (PVL) I don’t like to be in

public with lesbians who |

Я не люблю быть в обществе в сопровождении ярко |

.51 |

|

|

R-LIH-19 (PVL) I act as if

my lesbian partners are simply friends. |

Я веду себя так, как будто мои гомосексуальные |

.73 |

|

|

R-LIH-20 (PVL) When

speaking of my lesbian partner/lover, I |

Когда я рассказываю о своей партнерше, я говорю |

.78 |

|

|

R-LIH-21 (PVL) When

speaking of my lesbian partner, I change |

когда я рассказываю о своей партнерша, я говорю о |

.68 |

|

|

Lesbian Cultural Awareness (LCA) |

|

|

.75 |

|

R-LIH-22 (LCA) I am

familiar with lesbian culture (bars, support |

Я знакома с лесбикультурой (бары, группы |

.69 |

|

|

R-LIH-23 (LCA) I am aware

of the history concerning the |

Я знаю историю развития общества лесбиянок и |

.62 |

|

|

R-LIH-24 (LCA) I am

familiar with lesbian festivals and confer- |

Я знакома с лесбийскими фестивалями и |

.74 |

|

Figure 1. Parallel analysis scree plots

All four subscales exhibited high internal consistency: α = .75 (Lesbian Cultural Awareness); α = 85 (Public Visibility as a Lesbian); α = .85 (Connection to the Lesbian Community); and α = .85 (Public Identification as a Lesbian) (see Table 2). Interestingly, items from the U.S. LIHS loaded differently with the Russian sample. For instance, the subscale Attitude toward Other Lesbians loaded onto Connection with the Lesbian Community, and was consolidated as one subscale. Two new subscales emerged: Public Visibility as a Lesbian and Lesbian Cultural Awareness. This was likely due to differences between the United States and Russia, which are discussed in greater detail below. The alpha for the new LIHS total scale is .88.

Discussion

Similarities and differences in the experience and expression of lesbian internalized homo-negativity can shed light on the ways negative messages about lesbian identity are culture-bound or shared, and how homo-negative messages are internalized. The results of the factor analysis and assessment of internal consistency suggest that the four subscale Russian-version LIH may comprise useful measures for assessing IH in sexual minority women in Russia. Not surprisingly, three subscales failed to be retained following the factor analysis. The Moral and Religious Attitudes toward Lesbians subscale includes items such as “female homosexuality is a sin,” “growing up in a lesbian family is detrimental for children,” and the reversed item, “female homosexuality is an acceptable lifestyle.” This subscale captures dominant social attitudes rooted in moral and religious teachings, and such a measure may not carry over into the Russian context.

Russia remains one of the least religious societies in the world, with as few as 7 % of adults reporting weekly attendance in religious activities (Pew Research Center, 2017). Thus it is unclear whether religious teachings censuring homosexuality have made it into the popular discourse. In addition, the mean age of the sample, 32, suggests that many of these women were raised during the late Soviet or early years of post-communist transition, and thus prior to the ascendance of the Russian Orthodox Church in the latter part of the first decade of the 21st century. Although many people are likely to report identification as Russian Orthodox, it is unclear whether that identification is related to endorsement of, or exposure to, the Russian Orthodox Church’s religious doctrine or messages related to homosexuality, or even whether GLB individuals participate in organized religious services at all. Protestant and other Christian faiths have been restricted in Russia by recent laws (Newsweek, September 15, 2016); therefore, there are a limited number of organized faiths, including ones that might be affirming of GLB people, besides the Russian Orthodox faith.

Another subscale, Attitudes toward Other Lesbians, failed to be a valid measure in this sample. Some of the items —“I feel comfortable with the diversity of women who make up the lesbian community,” “I wish some lesbians wouldn’t flaunt their lesbianism. They only do it for shock value and it doesn’t accomplish anything positive” — assume that there are visible and “out” lesbian communities, and that some lesbians are outspoken and public with their sexual orientation. Given Russia’s current political context, with Russia’s most “out” lesbian, Masha Gessen, having departed Russia in 2013 for the United States (The Guardian, 2013), it is understandable that these items do not reflect contemporary Russian lesbian communities. Although lesbians in Russia remain politically active, and are doing a great deal of advocacy for GLB Russians, their capacity to organize formally has been severely restricted with recent policy changes (Horne, et al., 2009; Newsweek, 2016; Stella, 2015). In fact, it may be that the Lesbian conference where the data for this study were collected was one of the few large public gatherings of lesbians in Russia.

Finally, no items from the Personal Feelings about Being a Lesbian were found to be valid. Items on this measure, including, “I hate myself for being attracted to other women,” “I am proud to be a lesbian,” and “I feel bad for acting on my lesbian desires,” may reflect lesbian identity developed through an individualistic, Western Judeo-Christian-influenced tradition that emphasizes personal responsibility, sin, and shame in relation to same-sex desires (Tozer & Hayes, 2004; Lease, Horne, & Noffsinger-Frazier, 2005). This finding mirrors the results of Horne et al. (2009), in a study where they found a variation from Western-conceptualized internalized homo-negativity among their Russian participants. There was a noticeable absence of personal shame or internalized hatred about being GLB in personal narratives; rather, Russian interviewees appeared to have a strong sense of personal acceptance of their GLB identities, but intensive fear and concern about being perceived within society as homosexual (i.e., as different), and thus being targeted for being non-normative. An emerging emphasis on sin and religious condemnation of homosexuality within the current Russian Orthodox doctrine is likely to change this construct of internalized homo-negativity.

In comparison to the results from participants drawn for the sample that was used to develop the original LIHS (Szymanski & Chung, 2001), Russian means for internalized homo-negativity were slightly higher, (Connection with the Lesbian Community: Russian mean = 2.8, U.S. mean = 2.36; Public Identification as a Lesbian: Russian mean = 3.4, U.S. mean = 2.57). Although the results are not directly comparable since they are adapted subscales, the higher means of IH in Russia is somewhat surprising, given that the Russian sample was comprised of “out” women in Russia who were comfortable attending a public lesbian forum. These higher means among Russian lesbian women may reflect the repressive sociopolitical context.

Limitations

There are many limitations to our study, including the fact that it tested a geographically limited sample that included women primarily from a Russian urban setting, and women who were willing to self-identify as lesbian, as well as to meet publicly. The use of a self-report measure is also a limitation.

The study’s sample size remains a significant limitation, although the strong loadings in spite of it are promising. Our findings demonstrated that factor loadings across three subscales consisting of more than 5 items, loaded above 0.5–loading levels which Osborne and Costello (2009) note are “desirable and indicate a solid factor” (p. 138). The fourth subscale, Lesbian Cultural Awareness, included three items that loaded above 0.5, and thus this subscale should be examined in future research with a larger sample size.

Even so, we were cautious in approaching the cross-cultural validity of the Russian language LIHS, and included only items with strong communalities exceeding 0.5. According to Preacher and MacCallum (2002, p. 160), “As long as communalities are high, the number of expected factors is relatively small, and model error is low (a condition which often goes hand-in-hand with high communalities), researchers and reviewers should not be overly concerned about small sample sizes.” Indeed, given the fact that it will be challenging to procure a large sample of Russian lesbian women, we elected to provide this reliable and structurally valid adapted instrument developed from a smaller sample, so that other researchers can conduct research on IH among Russian sexual minority women.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, the use of a Russian version LIHS may be of use to contemporary Russian researchers exploring internalized homo-negativity. Future research may focus upon the convergent validity of this measure with other indices that correlate highly with IH, such as loneliness, depression, self-esteem, and other constructs. It may be beneficial to utilize this measure in combination with research on anti-GLB laws and policies, and to determine how such measures may shape the internalized experience of GLB Russians. This Russian version was inversely correlated with outness, and suggests that it may demonstrate divergent validity with measures of GLB pride, acceptance, and self-disclosure. Finally, this measure adds to an assessment that can be used to explore contemporary lesbian identity in Russia.

References

Abdi, H. & Williams, L.J. (2010). Principal component analysis. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: Computational Statistics, 2(4), 433–459. doi:10.1002/wics.101

Amadio, D.M. (2006). Internalized heterosexism, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems among lesbians and gay men. Addictive Behaviors, 31, 1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.08.013

Allen, D.J. & Oleson, T. (1999). Shame and internalized homophobia in gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 37(3), 33–43. doi: 10.1300/J082v37n03_03

Anderson, R. & Fetner, T. (2008). Economic inequality and intolerance: Attitudes toward homosexuality in 35 democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 942–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00352.x

Bayer, V., Robert-McComb, J.J., Clopton, J., & Reich, D.A. (2016). Investigating the influence of shame, depression, and distress tolerance on the relationship between internalized homophobia and binge eating in lesbian and bisexual women. Eating Behaviors, 24, 39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.12.001

Essig, L. (1999). Queer in Russia: A story of sex, self, and the other. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Flebus, G.B., & Montano, A. (2009). Contribution to the Italian translation and adaptation of the Lesbian Internalized Homophobia Scale of Szymanski and Chung. Bollettino di Psicologia Applicata , 258(56), 23–32.

Healey, D. (2002). Homosexual existence and existing socialism: New light on the repression of male homosexuality in Stalin’s Russia. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 8, 349–378.

Herek, G.M., Cogan, J.C., Gillis, J.R., & Glunt, E.K. (1997). Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 2, 17–25.

Herek, G.M., Gillis, J.R., & Cogan, J.C. (2009). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 32–43. doi: 10.1037/a0014672

Horne, S.G., Ovrebo, E., Levitt, H.M., & Franeta, S. (2009). Leaving the herd: The lingering threat of difference for same-sex identities in post-communist Russia. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 6, 108–122. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2009.6.2.88

Horne, S.G., Maroney, M., Zagryazhskaya, E., & Koven, J. (2017). Attitudes towards Gay and Lesbian individuals in Russia: An exploration of the interpersonal contact hypothesis and personality factors. Unpublished manuscript.

Karlinsky, S. (1989). Russia’s gay culture and literature: The impact of the October Revolution. In M. Duberman, M. Vicinus, & G. Chauncey Jr. (Eds.), Hidden from history: Reclaiming the gay and lesbian past (pp. 348–364). New York: New American Library.

Lease, S., Horne, S.G., & Noffsinger-Frazier, N. (2005). Affirming faith experiences and psychological health for Caucasian lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 378–388. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.378

Levada Center (2015). Homophobia. Retrieved from http://www.levada.ru/en/2015/06/10/homophobia/

Osborne, J.W. & Costello, A. B. (2009). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pan-Pacific Management Review, 12(2), 131–146. Retrieved from: http://pareonline.net/pdf/v10n7.pdf

Meyer, I.H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Moradi, B., van den Berg, J., & Epting, F. (2009). Intrapersonal and interpersonal manifestations of antilesbian and gay prejudice: An application of personal construct theory. Threat and guilt aspects of internalized antilesbian and gay prejudice: An application of personal construct theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 119–131. doi: 10.1037/ a0014571

Morandini, J.S., Blaszczynski, A., Dar-Nimrod, I., & Ross, M.W. (2015). Minority stress and community connectedness among gay, lesbian and bisexual Australians: a comparison of rural and metropolitan localities. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39(3), 260–266. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12364

Newcomb, M.E. & Mustanski, B. (2010). Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003

Newsweek (September 15, 2016). A new Russian law targets evangelicals and other foreign religions. Retrieved from http://www.newsweek.com/vladimir-putin-russia-foreign-religioncrackdown-498551

Nguyen, T.Q., Poteat, T., Bandeen-Roche, K., German, D., & Hai, Y. (2016). The Internalized Homophobia Scale for Vietnamese sexual minority women (IHVN-W): Conceptualization, factor structure, reliability, and associations with hypothesized correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(6), 1329–1346. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0694-6

Pew Research Center. (2013, June 4). The global divide on homosexuality: Greater acceptance in more secular and affluent countries. Retrieved from http://www.pewglobal.org/2013/06/04/ the-global-divide-on-homosexuality

Pew Research Center. (2017, May 10). Religious commitment and practices. Retrieved from http:// www.pewforum.org/2017/05/10/religious-commitment-and-practices

Preacher, K.J. & MacCallum, R.C. (2002). Exploratory factor analysis in behavior genetics research: Factor recovery with small sample sizes. Behavior Genetics, 32, 153–161. doi: 10.1023/A:1015210025234

Puckett. J.A., Levitt, H.M., Horne, S.G., & Hayes-Skelton, S.A. (2015). Internalized heterosexism and psychological distress: The mediating roles of self-criticism and community connectedness. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2, 426–435. doi: 10.1037/ sgd0000123

R Core Team (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Retrieved from: https://www.R-project.org

Revelle, W. (2016) How to: Use the psych package for factor analysis and data reduction. Retrieved from http://personality-project.org/r/psych/HowTo/factor.pdf

Russell, G.M. & Bohan, J.S. (2006). The case of internalized homophobia: Theory and/as practice. Theory & Psychology, 16, 343–366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0959354306064283

Shidlo, A. (1994). Internalized homophobia: Conceptual and empirical issues in measurement. In B. Greene & G. Herek (Eds.), Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 176–205). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Stella, F. (2015) Lesbian Lives in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia: Post/Socialism and Gendered Sexualities. Series: Genders and sexualities in the social sciences. Palgrave Macmillan: Basing-stoke.

Szymanski, D.M. & Chung, Y.B. (2001). The lesbian internalized homophobia scale: A rational/ theoretical approach. Journal of Homosexuality, 41(2), 37–52. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_03

Szymanski, D. M., & Kashubeck-West, S. (2008). Mediators of the relationship between internalized oppressions and lesbian and bisexual women’s psychological distress. The Counseling Psychologist, 36, 575–594. doi: 10.1177/0011000007309490

Szymanski, D.M., Kashubeck-West, S., & Meyer, J. (2008a). Internalized heterosexism: measurement, psychosocial correlates, and research directions. The Counseling Psychologist, 36(4), 525–574.

Szymanski, D.M., Kashubeck-West, S., & Meyer, J. (2008b). Internalized heterosexism: A historical and theoretical overview. The Counseling Psychologist, 36(4), 510–524. doi: 10.1177/ 0011000007309489

The Guardian (2013, August). As a gay parent I must flee Russia or lose my children. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/aug/11/anti-gay-laws-russia

Tozer, E. & Hayes, J. (2004). Why do individuals seek conversion therapy? The role of religiosity, internalized homo-negativity and identity development. The Counseling Psychologist, 32(5), 716–740. doi: 10.1177/0011000004267563

Watson, L.B., Grotewiel, M., Farrell, M., Marshik, J., & Schneider, M. (2015). Experiences of sexual objectification, minority stress, and disordered eating among sexual minority women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39, 458–470. doi: 10.1177/0361684315575024

Weinberg, G. (1972). Society and the healthy homosexual. Boston, MA. Alyson Press.To cite this article: Horne Sh. G., Maroney M. R., Geiss M. L., Dunnavant B. R. (2017). The reliability and validity of a Russian version of the Lesbian Internalized Homophobia Scale. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 10 (2), 5-20.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.