The value sphere of native and newcomer youth in their subjective assessment of the environment of a megalopolis

Abstract

Currently, in the Russian Federation more and more attention is being paid to the quality of human capital. The innovative future of the country as a whole and its regions in particular depends on having young people with an active lifestyle, a high level of education, and a desire to be included in the development process of their country, region, city, or town. In most regions of the Russian Federation, programs and projects are supported that promote the self-actualization of young people and create conditions to ensure a full and rich life for the younger generation. But, despite these measures, as well as major government funding, the process of active internal migration and the outflow of talented young people from provincial areas into the central regions, as well as from rural to urban settlements, lead to the significant negative skewing of socioeconomic development in the regions of the Russian Federation. Thus, these are the issues: which characteristics of life in a megalopolis are valuable and attractive to young people and are there differences in the images of a big city held by native young people and newcomers.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the characteristics of the value-sense and need-motivational spheres of native and newcomer youth in a megalopolis as well as to reveal the specifics of their images of a contemporary megalopolis. A comprehensive study conducted in Ekaterinburg among young people in the senior classes of secondary schools, colleges, and universities, as well as among young working men and women (N = 1108; ages 17-25), disclosed the base values in the subjective evaluation of the environment of a megalopolis by native and newcomer youth. In accordance with the objectives of the study, the sample was divided into two contrasting groups: native residents of Ekaterinburg (living there since birth) 437; newcomer residents of Ekaterinburg (living there fewer than 3 years) who were actively adapting to life in the megalopolis at the time the of the study 671 people. The study was conducted with the use of age-specific characteristics of a battery of diagnostic instruments. This article describes the specifics of the value orientations and evaluations of the image of the city among native and newcomer young people. Value determinants of the assessment of the environment of the big city by the native respondents for the most part had a social focus, and at the same time this category of young people generally did not seek to dominate and manage the environment of the megalopolis. The newcomer young people had an intense orientation to values. This orientation ensured their adaptation to and formation of a positive image of the city as a potential location for their personal self-realization.

Received: 29.03.2015

Accepted: 30.09.2015

Themes: Social psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2015_4/psychology_2015_4_12.pdf

Pages: 139-154

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2015.0412

Keywords: values of young people, identification with the city, opportunities and risks in a megalopolis, adolescence, megalopolis, internal migration of young people

Introduction

The modern world is a civilization of cities. The development of society, technology, culture, wealth, and new knowledge are today the primary functions of cities but not of other socio-territorial formations. Cities are now centers of freight logistics, information, and social streams. Therefore, the fullness of city life — especially if we speak about a large city with multiple events and a large number of alternatives for work, leisure, education, sources of information, services, and other benefits (Kogan, 1990) — makes this type of settlement the most attractive location for many groups of people. This attraction is also evidenced by the population growth of large Russian cities (including as a result of internal migration) and the sparser rural population (Volkova, Sokolov, & Terentyev, 2015).

The development of modern cities depends on their human resources — that is to say, on their populations. Therefore, to attract and retain in the city the “creative class” — young people — the city has to create conditions for its future development. To this end, many cities have implemented targeted programs of social support for young people and the formation of specific conditions of the urban environment conducive to the maximum fulfillment of the capacity of their young residents. Thus, in the strategic development plan of the municipality of Ekaterinburg (Strategic development plan of Ekaterinburg through 2020, 2010), one of the priorities is the development of conditions for active self-determination and self-realization of young people as the carriers of innovation. However, the socioeconomic-development strategy for Moscow (Strategy for the socio-economic development of Moscow through 2025, 2012) emphasizes that one of the major challenges will be the reduction of the population of 20-35 year-olds by a third; as a result, Moscow will become a city with a strongly deformed age structure. In connection with these trends special attention in the development strategy of Moscow is paid to the mechanisms for creating special conditions to attract the people necessary for a megalopolis: representatives of “the creative class,” highly qualified specialists, as well as active, talented youth.

A significant proportion of young people migrate actively inside the country. For example, more than 70% of high school graduates from small settlements moved to the Central federal region. And, in 2013, 114,347 people from rural settlements arrived in the cities of the Ural federal region; of them 39,754 people were from other regions of the Russian Federation and 74,593 migrated inside the Ural federal region[1] (Migration inside Russia by the territories of arrival and departure, 2014).141

The experience of living in certain places affects the perceptions and environmental preferences of people. They may prefer or look for what they are accustomed to (Hauge, 2007). When they transfer their residence experience in other areas to the urban environment, certain risks of pseudourbanization are created. But also arriving in cities are young people with increasing experience of interaction within an urban community; they are changing themselves more and more, and the city and its way of life have already become for them a measure for evaluating environmental living conditions. The acquired experience of life in a city creates the individual stories of young people as citizens who identify themselves with the city. Identity with place is formed through a combination of human-ascribed meanings and values of a particular location (for example, a city) and various features (Lalli, 1992). Thus the urban environment becomes for young people a place of opportunities for self-realization. This process takes place with a background of the risks of urban life, and the goals that young people set reflect their need-motivational bases of personality.

A city concentrates opportunities, but young people are quite aware of the obvious disadvantages of the artificial, highly dynamic environment of a city (Kruzhkova, 2014); this environment runs counter to the natural conformity built up for thousands of years by the rural way of life that was typical for the majority of the population of Russia one hundred years ago (Bondyreva & Kolesov, 2004). However, the urban lifestyle is highly appealing to young people. So, since 2006 the capital of the Sverdlovsk region, Ekaterinburg, has experienced growth in its population, mainly because of positive net migration (Ekaterinburg, 2015), while the rural population of the Sverdlovsk region has aged and declined.

Many legitimate questions can be asked: What is important for young people in their evaluations of life in a city? Are there differences in the way native young people and immigrants understand a city? What values (and desires) form the basis for assessing the attractiveness / unattractiveness of a city from the perspective of young people?

Thus, the purpose of our study was to determine the specific value orientations of native and newcomer youth and the role these values play in their assessments of the environment of a megalopolis (in our study, Ekaterinburg).

Methods

The total sample of the study was 1108 adolescent respondents (17-25 years). The study involved young men and young women (34% and 66%, respectively) who were students in the senior classes of secondary schools, colleges, and universities in Ekaterinburg, as well as working young people. In accordance with the objectives of the study the sample was divided into two contrasting groups: native residents of Ekaterinburg (living there since birth) 437; newcomer residents of Ekaterinburg who were actively adapting to life in the megalopolis at the time of the study (living there fewer than 3 years) 671 people. Subsamples of the contrasting groups were balanced by sex and type of education (in each of the 16 categories there were at least 30 observations).

The following diagnostic instruments were used as the research methods:

- A questionnaire by I. V. Vorobyeva and О. V. Kruzhkova to gauge subjective assessments of stress factors in the environment of a big city. The questionnaire consists of 42 items describing physical, social, and other dynamic factors that may be perceived by residents of large cities as stressful. Subjects assess the items on a scale of 0 (absolutely no worries) to 4 (high emotional stress). The items are combined into eight groups: real risks and threats (factors that are dangerous for human life and health and significantly reduce the quality of life of the citizens — in particular, the presence of air and water pollution, the risk of becoming a victim of crime, the probability of a car accident, terrorist threats, etc.), information and dynamic loads (factors that are associated with the need to receive, process, and respond to multiple stimuli coming from the external environment in a short period of time), social crowding (factors that stimulate the emergence of a subjective feeling of a lack of freedom in social interaction because of multiple contacts in the urban environment and social obligations prescribed by the existence of expectations in relation to people as townspeople), transport risks (factors that are a result of the interaction of the individual and public transport), orientation problems (difficulties in the allocation of the functional areas of the space, the unclear structure of the city or part of the system of streets, disorientation in specific places of the city), indifference (factors that encourage a sense of loneliness and insecurity while being in a crowded urban environment), migration risks (interactions with nonresident and foreign nationals newly arrived in the city), the homogeneity of the visual environment (factors related to the monotony of the external elements of the urban environment) (Kruzhkova, 2014).

- The values questionnaire of S. H. Schwartz (Bogomaz & Litvina, 2015) for the construction of a values-based personality profile. This checklist is based on the theory of basic values of Schwartz (1992) and is adapted for Russian sociocultural conditions (Schwartz, Butenko, Sedova, & Lipatova, 2012). It consists of 57 statements by a hypothetical person. Respondent estimates the similarity with the man himself, as described in the text and expresses the degree of his agreement with the statements on a 6-point scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me). The results are grouped into 19 values, which are a guide to building human behavior. They differ from each other in the direction and focus of the underlying basic individual or group needs. Diagnosis is carried out according to the following scales: independence (actions), independence (thoughts), stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power (resources), power (dominance), reputation, safety (public), security (personal), conformism (rules), conformism (interpersonal), traditions, modesty, kindness (duty), kindness (concern), universalism (concern for others), universalism (care about nature), universalism (tolerance).

- The scale of identification with a city of M. Lalli (Miklyaeva & Rumyantseva, 2011). The scale consists of 20 statements to which the respondent expresses agreement or disagreement on a Likert scale from 1 (disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Approved methodologies are arranged in five semantic blocks that are the basis for the interpretation of results, which are the external value of total attachment with the past, the perception of intimacy, and goal-setting (Lalli, 1992).

For the statistical analysis of the results of the study the IBM SPSS Statistic 19 package of was used. In order to solve the research problems the following analyses were applied:

- Descriptive statistics that reflect the general trends of the studied parameters of the respondents

- Comparative analysis (Student’s t-Test for independent samples) to detect statistically significant differences between subgroups in the main sample

- Linear regression analysis to determine the value of predictors of the subjective evaluation of the urban environment by the respondents

- Pearson correlation analysis to identify the structure of the relationship of components of the subjective evaluation of the urban environment by the respondents

Results

Assessment of the value orientations of young people in the subgroups native and newcomers allowed us to allocate their value priorities and differences in life benchmarks (Table 1).

Table 1. Average means of the values of natives and newcomers

|

|

Native residents |

Newcomer residents | ||

|

Indicators |

Average mean |

Standard deviation |

Average mean |

Standard deviation |

|

Independence (actions) |

3.569 |

0.948 |

3.525 |

0.894 |

|

Independence (thoughts) |

3.497 |

0.914 |

3.577 |

0.850 |

|

Stimulation |

3.301 |

0.928 |

3.318 |

0.918 |

|

Hedonism |

3.610 |

1.007 |

3.564 |

0.908 |

|

Achievement |

3.166 |

0.883 |

3.214 |

0.829 |

|

Power (resources) |

2.559 |

1.164 |

2.524 |

1.107 |

|

Power (dominance) |

2.369 |

1.181 |

2.376 |

1.140 |

|

Reputation |

3.598 |

0.965 |

3.615 |

0.935 |

|

Safety (public) |

3.235 |

1.052 |

3.382 |

0.934 |

|

Security (personal) |

3.389 |

0.977 |

3.507 |

0.883 |

|

Conformism (rules) |

2.705 |

1.113 |

2.836 |

1.051 |

|

Conformism (interpersonal) |

2.805 |

1.066 |

2.913 |

0.963 |

|

Traditions |

2.837 |

1.111 |

3.026 |

1.014 |

|

Modesty |

2.938 |

0.959 |

3.026 |

0.875 |

|

Kindness (duty) |

3.813 |

1.051 |

3.883 |

0.947 |

|

Kindness (concern) |

3.911 |

0.940 |

3.960 |

0.975 |

|

Universalism (concern for others) |

3.241 |

1.017 |

3.372 |

0.940 |

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

2.775 |

0.998 |

2.886 |

0.985 |

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

3.131 |

1.043 |

3.238 |

0.957 |

In general, the value profiles of the newcomers were more pronounced than those of the native respondents. Nevertheless, there was an overall trajectory of this profile in both groups. The leading value was goodwill in both its individualized focus on a sense of duty and its social focus on concern for ones group and its members. Also, the young people were focused on the freedom to define their own actions, and they expressed the desire for pleasure and a sense of gratification; for them the image of themselves that they broadcast into the surrounding social space is significant. Overall, this finding corresponds to the age-related goals of youth (Huhlaeva, 2002). Young people are focused less on their impact in relation to others. They have no sense of the possibility of using tools or instruments to control others through personal influence (authority, power, status, etc.) or any other material and social resources.

Estimates of the relationship to the urban environment in the contrasting groups of native young people and newcomers were detected by comparative analysis using the parametric Students t-Test for independent samples. These comparative results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Results of comparative analysis on the Student s t-Test

|

Value on the t-Test |

Indicators |

Level of significance |

Average value, mean | |

|

Native residents |

Newcomer residents | |||

|

Information and dynamic loads |

2.638 |

0.008** |

0.962 |

0.826 |

|

Social crowding |

3.200 |

0.001** |

1.090 |

0.928 |

|

Orientation problems |

2.486 |

0.013* |

1.137 |

0.994 |

|

Indifference |

2.284 |

0.023* |

1.922 |

1.778 |

|

Migration risks |

6.252 |

0.000** |

1.901 |

1.411 |

|

Homogeneity of the visual environment |

4.094 |

0.000** |

1.161 |

0.895 |

|

Safety (public) |

-2.375 |

0.018* |

3.234 |

3.382 |

|

Security (personal) |

-2.033 |

0.042* |

3.389 |

3.507 |

|

Traditions |

-2.870 |

0.004** |

2.837 |

3.026 |

|

Universalism (concern for others) |

-2.159 |

0.031* |

3.241 |

3.372 |

|

Affection |

9.668 |

0.000** |

3.882 |

3.294 |

|

Connection with the past |

10.396 |

0.000** |

3.340 |

2.716 |

|

Perception of proximity |

3.522 |

0.000** |

3.223 |

3.001 |

|

Targeting |

-3.299 |

0.001** |

2.908 |

3.178 |

* p < 0.05; **p< 0.01.

Of the 32 variables, 14 (44% of the possible differences in all studied traits) were found to be statistically significant. This result confirms the contrast in the studied groups with respect to the system of individual life guidance, attitude to the city, and perception of the stress factors that exist in it.

Based on these results, we hypothesized that native and newcomer residents of the city have different value-semantic frameworks that determine the perception of risks and stress factors in the urban environment and the value of this perception for individual, underlying identification with the city. This assumption was verified by regression analysis for each group of respondents. The results are shown in Tables 3-6.

Table 3. Regression models of the determination of values in relation to the city in the sample of native residents

|

|

Features and elements of the regression model | |||||

|

Dependent variables |

F-criterion |

Significance level of the reliability models |

General explanation by model variance |

Elements of the model |

Factor β |

Significance level of the elements of the model |

|

External value of the city |

14.765 |

0.000** |

12% |

Safety (public) |

0.142 |

0.011* |

|

Security (personal) |

-0.118 |

0.032* | ||||

|

Conformism (rules) |

0.155 |

0.006** | ||||

|

Traditions |

0.195 |

0.000** | ||||

|

Affection |

14.896 |

0.000** |

17.2% |

Independence (actions) |

-0.153 |

0.006** |

|

Hedonism |

0.114 |

0.047* | ||||

|

Power (resources) |

-0.117 |

0.016* | ||||

|

Reputation |

0.118 |

0.035* | ||||

|

Safety (public) |

0.244 |

0.000** | ||||

|

Traditions |

0.192 |

0.000** | ||||

|

Connection with the past |

8.598 |

0.000** |

9.1% |

Independence |

-0.113 |

0.044* |

|

(thoughts) |

|

| ||||

|

Hedonism |

0.135 |

0.019* | ||||

|

Power (resources) |

-0.115 |

0.021* | ||||

|

Traditions |

0.185 |

0.001** | ||||

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.157 |

0.002** | ||||

|

Perception of proximity |

18.886 |

0.000** |

14.9% |

Independence |

-0.147 |

0.003** |

|

(thoughts) Safety (public) |

0.215 |

0.000** | ||||

|

Traditions |

0.202 |

0.000** | ||||

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.109 |

0.036* | ||||

|

Targeting |

15.041 |

0.000** |

14.9% |

Power (resources) |

-0.103 |

0.024* |

|

Safety (public) |

0.182 |

0.001** | ||||

|

Conformism (rules) |

0.182 |

0.001** | ||||

|

Traditions |

0.179 |

0.001** | ||||

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Table 4. Regression models of the perception of stress factors in the urban environment in the sample of native residents

|

|

Features and elements of the regression model | |||||

|

Dependent variables |

F-criterion |

Significance level of the reliability models |

General explanation by model variance |

Elements of the model |

Factor β |

Significance level of the elements of the model |

|

Real risks and threats |

6.831 |

0.000** |

7.3% |

Achievement |

0.139 |

0.017* |

|

Power (resources) |

-0.123 |

0.015* | ||||

|

Security (personal) |

0.136 |

0.018* | ||||

|

Modesty |

-0.162 |

0.003** | ||||

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.145 |

0.008** | ||||

|

Information and dynamic loads |

12.841 |

0.000** |

10.6% |

Independence (thoughts) |

-0.166 |

0.004** |

|

Traditions |

0.104 |

0.045* | ||||

|

Kindness (concern) |

-0.218 |

0.000** | ||||

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.143 |

0.006** | ||||

|

Social crowding |

9.075 |

0.000** |

5.9% |

Hedonism |

-0.119 |

0.028* |

|

Kindness (concern) |

-0.173 |

0.002** | ||||

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.112 |

0.024* | ||||

|

Transport risks |

4.938 |

0.008** |

2.2% |

Hedonism |

-0.153 |

0.005** |

|

Achievement |

0.140 |

0.010* | ||||

|

Orientation problems |

5.934 |

0.000** |

7.6% |

Hedonism |

-0.162 |

0.006** |

|

Achievement |

0.249 |

0.001** | ||||

|

Conformism (rules) |

-0.174 |

0.007** | ||||

|

Traditions |

0.127 |

0.028* | ||||

|

Kindness (concern) |

-0.186 |

0.002** | ||||

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.119 |

0.030* | ||||

|

Indifference |

10.291 |

0.000** |

6.7% |

Achievement |

0.197 |

0.000** |

|

Power (resources) |

-0.144 |

0.004** | ||||

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.119 |

0.017* | ||||

|

Migration risks |

4.734 |

0.009** |

2.1% |

Reputation |

0.124 |

0.013* |

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

-0.124 |

0.013* | ||||

|

Homogeneity of the visual environment |

6.065 |

0.000** |

5.3% |

Achievement |

0.152 |

0.020* |

|

Conformism (rules) |

-0.153 |

0.012* | ||||

|

Kindness (concern) |

-0.210 |

0.000** | ||||

|

Universalism (care about nature |

0.198 |

0.000** | ||||

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Table 5. Regression models of the determination of values in relation to the city in the sample of newcomer residents

|

|

Features and elements of the regression model | |||||

|

Dependent variables |

F-criterion |

Significance level of the reliability models |

General explanation by model variance |

Elements of the model |

Factor β |

Significance level of the elements of the model |

|

External value of the city |

13.360 |

0.000** |

3.8% |

Power (dominance) |

0.159 |

0.000** |

|

Safety (public) |

0.108 |

0.005** | ||||

|

Affection |

8.881 |

0.000** |

2.6% |

Power (resources) |

0.111 |

0.004** |

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.114 |

0.003** | ||||

|

Connection with the past |

6.770 |

0.000** |

5.8% |

Independence (thoughts) |

-0.162 |

0.001** |

|

Hedonism |

0.102 |

0.022* | ||||

|

Traditions |

0.089 |

0.032* | ||||

|

Kindness (concern) |

-0.128 |

0.011* | ||||

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.101 |

0.020* | ||||

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

0.091 |

0.037* | ||||

|

Perception of proximity |

10.561 |

0.000** |

4.5% |

Power (resources) |

0.096 |

0.012* |

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.135 |

0.001** | ||||

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

0.089 |

0.032* | ||||

|

Targeting |

15.605 |

0.000** |

4.5% |

Hedonism |

0.132 |

0.001** |

|

Conformism (rules) |

0.161 |

0.000** | ||||

*p< 0.05; **p< 0.01.

According to Table 3, the identified models had a high percentage of explained variance, which allows us to speak about the axiological basis of native young people in relation to the city. The most frequently identified determinants of attitude toward the city were the value of safety (public) and the value of traditions. Both values are socially oriented and require the maintenance and preservation of sociocultural foundations to ensure the stability of society.

According to Table 4, the regression models that explain the assessment of risk in the urban environment by native residents in general have small dispersion loads, but one of the most powerful models is the information and dynamic loads presented in the city. Here, the high dynamics of life in the city, the richness of its information environment, become annoying, and these negative assessments factor into the prevalence of a conservative and traditionalist orientation. Curiously, one's allegiance to ones own group significantly reduces the intensity of the negative assessment of the urban environment; this reduction is a consequence of the effect of in-group favoritism.

According to Table 5, the identification with the city among young newcomers was weakly determined by their values, as confirmed by the low regression weights of the models. Various predictors in the derived structures characterized the high degree of differentiation of axiological factors.

In Table 6, the most axiological determinants of the presence of stress factors were the indifference of the inhabitants of the city to each other and the presence in the urban environment of real risks and threats to human life and health. In most of the models, a significant predictor of the presence of stressors in the urban environment was favoring the value of universalism (tolerance). A lack of readiness for understanding and accepting those who are different increases the sensitivity of a young person to the negative aspects of life in the city.

Table 6. Regression models of the perception of stress factors in the urban environment in the sample of newcomer residents

|

|

Features and elements of the regression model | ||||||

|

Dependent variables |

F-criterion |

Significance level of the reliability models |

General explanation by model variance |

Elements of the model |

Factor β |

Significance level of the elements of the model | |

|

Real risks and threats |

13.533 |

0.000** |

10.9% |

Power (dominance) |

-0.122 |

0.001** | |

|

Security (personal) |

0.125 |

0.005** | |||||

|

Traditions |

0.106 |

0.013* | |||||

|

Kindness (duty) |

0.168 |

0.000** | |||||

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.090 |

0.031* | |||||

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

-0.213 |

0.000** | |||||

|

Information and dynamic loads |

11.387 |

0.000** |

7.9% |

Conformism (interpersonal) |

0.093 |

0.025* | |

|

Traditions |

0.097 |

0.020* | |||||

|

Kindness (concern) |

-0.274 |

0.000** | |||||

|

Universalism (concern for others) |

0.111 |

0.025* | |||||

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

-0.103 |

0.024* | |||||

|

Social crowding |

9.285 |

0.000** |

5.3% |

Conformism (interpersonal) |

0.087 |

0.036* | |

|

Kindness (concern) |

-0.207 |

0.000** | |||||

|

Universalism (concern for others) |

0.111 |

0.025* | |||||

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

-0.127 |

0.006** | |||||

|

Transport risks |

4.634 |

0.001** |

2.7% |

Stimulation |

-0.105 |

0.017* | |

|

Conformism (rules) |

0.090 |

0.027* | |||||

|

Kindness (duty) |

0.140 |

0.002** | |||||

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

-0.102 |

0.020* | |||||

|

Orientation problems |

6.755 |

0.000** |

3.9% |

Conformism (interpersonal) |

0.084 |

0.043* | |

|

Traditions |

0.141 |

0.001** | |||||

|

Kindness (concern) |

-0.126 |

0.002** | |||||

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

-0.093 |

0.032* | |||||

|

Indifference |

12.003 |

0.000** |

11.2% |

Stimulation |

0.092 |

0.039* | |

|

Power (dominance) |

-0.130 |

0.001** | |||||

|

Conformism (interpersonal) |

0.084 |

0.045* | |||||

|

Kindness (duty) |

0.134 |

0.003** | |||||

|

Universalism (concern for others) |

0.132 |

0.007** | |||||

|

Universalism (care about nature) |

0.093 |

0.034* | |||||

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

-0.118 |

0.010* | |||||

|

Migration risks |

12.351 |

0.000** |

5.3% |

Achievement |

0.103 |

0.016* | |

|

Safety (public) |

0.130 |

0.002** | |||||

|

Universalism (tolerance) |

-0.221 |

0.000** | |||||

|

Homogeneity of the visual environment |

8.906 |

0.000** |

3.9% |

Safety (public) |

0.100 |

0.029* | |

|

Traditions |

0.117 |

0.005** | |||||

|

Kindness (concern) |

-0.182 |

0.000** | |||||

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

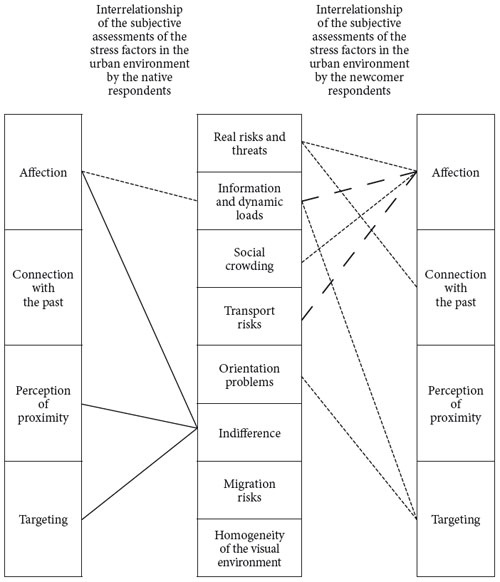

Studying the structural integrity and objectivity assessments of the urban environment by native youth and newcomers shows the differences in the relationships of positive and negative assessments (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The relationship between identification with the city and subjective assessments of stress factors in the urban environment by native and newcomer respondents. A thin solid line shows a positive correlation at p < 0.05; a thin dotted line shows a negative correlation at p < 0.05; a fat dotted line shows a negative correlation at p < 0.01.

The newcomer residents demonstrated orthodox attitudes toward the urban environment: positive identification with the city was inversely proportional to the negative assessment of stressful aspects of its life. Native residents are freer and have independent systems for positive and negative assessments of the urban environment.151

Discussion

The orientation of modern cities toward innovation and the formation of the global image of the city is not fully correlated with the value orientations of the young people living in them. In our study, for the younger generation the most important value that determined their behavior was giving priority to decisions in one’s own group and in the wider social community This value corresponds with the objectives of youth, which are implemented by means of social identification (Popova, 2005) through the transfer of the characteristics of group members to the individual. The association of youth within a community (or subculture) or their adherence to other social groups (online communities, political and social associations) often occurs spontaneously and in opposition to society as a whole, that gives rise to dangerous tensions in urban society and limits the prospects for the development of individuals and cities in a changing world (Simonova, 2010). The association of youth from diverse communities would be advisable as it would be more effectively in accordance with the objectives of the city. The desire of young people to be accepted and useful and to realize themselves as full members of a group can be the basis for active participation in voluntary activities, youth work, or other governmental, socio-oriented urban-development projects.

The associated dominant values of young people living in a megalopolis are personality-focused and conflict with the dominant, socio-focused values. The choice between individual and group interests is exacerbated when there are real or potential feelings of physical threat or of a threat to the social status of the individual. According to research data (Kruzhkova, 2014), about 30% of young people living in large cities are experiencing acute stress from the environment. It is obvious that their assessment of the urban environment is orthodox and stochastic; it is not dependent on the actual situation or on young peoples emotions and current relationship with the environment. This assessment can lead to impulsive acts, ill-considered decisions, a tendency to interrupt activities, and, as a result, difficulty in attaining self-realization in the environment of the megalopolis.

In our study, intensity in the expression of values was more characteristic of the newcomers to the city than of the native residents. The newcomers’ focus on security, traditions, ideas regarding ecology, justice, and tolerance underlined their more vulnerable position in the new-for-them environment of the megalopolis. Their demonstration of their openness to a new society and desire to be useful to it created a kind of adaptation resource for conflict-free entry into the environment of the city. This positive perception of the megalopolis meant that the young newcomers were less concerned than the natives about the presence of stress factors in the urban environment and assigned them less importance as a personal threat. However, adverse events that occur to a person directly can begin to determine the general attitude toward the city and its subjective assessment. Thus, newcomers were seen in a large number of correlations both of the subjective evaluation of the negative factors of living in the city and of the positive trend to identify with it (Table 6).

For the native residents another mechanism in the formation and evaluation of the image of the city was typical: negative situations distanced them from the processes of identification with the city. At the same time, for the young native people the obstacle to maintaining a positive image of the city was the indifference of the inhabitants of the megalopolis toward others; this attitude violates several basic needs of any person. The native residents were aware that in an emergency in an urban environment they must rely on themselves and not on the aid of others; this situation creates a zone distancing them from the environment of the city, but not in their dominant value orientations or in the difficult implementation of the development prospects of the city (Chernjavskaja, 2011).

The value determinants of the assessment of the environment of the big city in the native young people more often had a social focus, which indicates that the more people are included in a social community and the more comfortable they are in it, the more they have a positive image of the city and are willing to identify with it. Young people usually do not seek to dominate in this environment or to manage it; they are often more willing to act as executors than as initiators of changes. They are comfortable within the environment of cities, and their focus on goodwill and hedonism minimizes the sharpness of the perception of potential risks present in it

The young newcomers had a quite different position: for them, individualistic orientation values ensured the formation of a positive image of the city as a potential location for their personal self-realization. Such young people are more ready to accept the role of managers, leaders, and initiators of innovative processes in an urban environment than native young people. However, the intensity of this groups perception of risk increased under the influence of the rules and regulations that the young people had to comply with in order to integrate into the community. This load of social expectations made them more sensitive to the social, informational, dynamic, and physical stress factors of the urban environment.

Conclusions

First, the megalopolis had one of the most attractive living environments for these young men and women not only because of the localization of very comfortable living conditions but also because of the concentration of opportunities for personal self-realization, which is so relevant to young people. These youth were focused more on the process of social identification with the city and the search for social groups, which provide a sense of security and acceptance, than on the choice of individual strategies to realize their potential.

Second, the image of the city was different for native and newcomer young people. The young men and women born in the big city, on the one hand, gave a more objective assessment of it, pointing out both the pros and the cons of living in the city. The young newcomer residents, on the other hand, to a lesser extent considered the city an environment for the realization of their abilities. Their assessments of the urban environment were more situational and based on their personal experience, but they considered it an environment that promotes self-realization.

Third, the appeal of the megalopolis had different axiological foundations for native and newcomer young residents. For the first group the city was a familiar environment with prime opportunities for social interaction; for the second group it was a competitive environment that required adaptation and maximum realization of personal opportunities. For the newcomer young people, who were coming from a more active position in life, the city posed new challenges in the implementation of its development strategy.

Fourth, thus, the study of the axiological foundations of the subjective assessment of the environment of a megalopolis by different categories of young people living in it seems to be promising; it is in demand for the implementation of administrative functions for the development of human capital and for forming optimal migration policies in a region. In addition, research in the field of the environmental psychology of a city is quite rare in domestic science and does not allow us to form a comprehensive picture of the interaction between the urban environment and the people living in it. The present study is one of the fragments in the formation of a relatively new direction for Russian research.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Professor S. A. Bogomaz for scientific and methodological support of the project and genuine support of research in the psychology of the urban environment. The study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Humanities and the Government of the Sverdlovsk region, project 15-16-66024.

References

Bogomaz, S. A., & Litvina, S. A. (2015). Oprosnikovye metodi issledovaniy sredovoi identichnosty [Questionnaires on research methods on environmental identity]. Tomsk, Russia: National Research Tomsk State University.

Bondyreva, S. K., & Kolesov, D. V. (2004). Tradizii: Stabilnost i preemstvennost v zhizni obshestva [Traditions: Stability and continuity in society]. Moscow: MPSI; Voronezh, Russia: NPO MODEK.

Chernjavskaja, O. S. (2011). Osmislenie ponatia territorialnoi identichnosti [Understanding the concept of territorial identity]. Bulletin of the Vyatka State Humanitarian University, 4, 70-76. Ekaterinburg. (2015). Wikipedia. Retrieved from http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ekatermburg Hauge, A. L. (2007). Identity and place: A critical comparison of three identity theories. Architectural Science Review, 20(1), 44-51. doi: 10.3763/asre.2007.5007

Huhlaeva, О. V. (2002). Psihologia razvitia: Molodost, zrelost, starost [Developmental psychology: Youth, maturity, old age]. Moscow: Academy.

Kogan, L. B. (1990). Bitgorozhaninym [Being a citizen]. Moscow: Misl.

Kruzhkova, О. V. (2014). Individual determination of the subjective importance of urban environmental stress factors in the period of youth. Psikhologicheskie Issledovaniya, 7(34), 3. Retrieved from http://psystudy.ru

Lalli, M. (1992). Urban-related identity: Theory, measurement and empirical findings. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12, 285-303. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80078-7

Migration inside Russia by territories of arrival and departure (2014). National Population Census 2010. Retrieved from http://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/bl4_13/IssWWW.exe/Stg/d01/04-30. htm

Miklyaeva, A. V., & Rumyantseva, P. V. (2011). Gorodskai identichnost zhitela sovremennogo megapolisa: Resurs lichnogo blagopoluchia ili zona povishennogo riska? [Urban identity of the resident of a modern megalopolis: A resource for personal well-being or a high-risk area?]. St. Petersburg: Rech.

Popova, M. V. (2005). Stanovlenie personalnoi identichnosti v unosheskom vozraste [The formation of personal identity in adolescence] (Unpublished synopsis of a doctoral dissertation). Nizhny Novgorod, Russia: Gorky Nizhny Novgorod State Pedagogical University.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in experimental social psychology. New York: Academic Press.

Schwartz, S. H., Butenko, T. R, Sedova, D. S., & Lipatova, A. S. (2012). Utochnennai teoria bazovih individualnih cennostey: Priminenie v Rossii [A refined theory of basic individual values: For use in Russia]. Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 9(1), 43-70.

Simonova, I. A. (2010). Ot kulturnogo mnogoobrazia к mezhkulturnomu dialogu: Socialnay topologia subkulturnih soobshestv [From cultural diversity to intercultural dialogue: The social topology of subcultural communities]. Education and Science, 10, 88-99.

Strategic development plan of Ekaterinburg through 2020. (2010). Informational portal of Ekaterinburg. Retrieved fromhttp://www.ekburg.ru/.out/file/29765.pdf Strategy for the socioeconomic development of Moscow through 2025. (2012). Retrieved from http://ramenki.mos.ru/gosprogram/ 17.pdf

Volkova, O., Sokolov, A., & Terentyev, I. (2015). Issledovanie RBK: Pochemy vimiraut rossiiskie goroda [RBK Study: Why Russian cities are extinct]. RusBusinessConsulting: Society. Retrieved fromhttp://daily.rbc.ru/special/society/17/03/2015/5506d6979a79471b5dcfdcee

[1] The source shows the dynamic of migration within the country from 2011 to 2014, but at the same time for the bases index there were taken the results of 2010.

To cite this article: Kruzhkova, O. V., Vorobyeva, I. V., Bruner, T. I., Krivoshchekova, M.S. (2015). The value sphere of native and newcomer youth in their subjective assessment of the environment of a megalopolis. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 8(4), 139-154.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.