Mental Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Hardiness and Meaningfulness Reduce Negative Effects on Psychological Well-Being

Abstract

Background. The COVID-19 outbreak and the measures taken to curb it have changed people’s lives and affected their psychological well-being. Many studies have shown that hardiness has reduced the adverse effects of stressors, but this has not been researched in the Russian COVID-19 situation yet.

Objective. To assess the role of hardiness and meaningfulness as resources to cope with stress and minimize its effects on psychological well-being.

Design. The study was conducted March 24–May 15, 2020 on a sample of 949 people (76.7% women), aged 18–66 years (M = 30.55, Me = 27, SD = 11.03). The data was divided into four time-periods, cut off by the dates of significant decisions by the Russian authorities concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. The questionnaires were: Beck Anxiety and Depression Inventories, Symptom Check-list-90-R, Noetic Orientations Test, and Personal Views Survey-III.

Results. Welch’s ANOVA showed significant differences between the time-periods in meaningfulness, hardiness, anxiety, depression, and the General Symptomatic Index (GSI) (W = 4.899, p< 0.01; W = 3.173,p < 0.05; W = 8.096,p < 0.01; W = 3.244,p < 0.022; and W = 4.899,p < 0.01, respectively). General linear models for anxiety, depression, and GSI showed that biological sex, chronic diseases, self-assessed fears, and hardiness contributed to all of them. In all three models, hardiness had the most significant impact. Anxiety was also influenced by the time factor, both in itself and in its interaction with hardiness levels. With less hardiness, more anxiety occurred over time.

Conclusion. Hardiness was shown to be a personal adaptive resource in stressful situations related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Received: 15.08.2020

Accepted: 05.11.2020

Themes: COVID-19: psychological challenges

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2020_4/Psychology_4_2020_75-88_Epishin.pdf

Pages: 75-88

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2020.0405

Keywords: hardiness, meaningfulness, anxiety, depression, pandemic, COVID-19

Introduction

As of the middle of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has radically changed the daily lives of people worldwide. These changes cannot be explained only by the direct threat posed by this disease to people’s health or the health of their relatives. The measures that were taken by governments and health organizations to slow down and combat the pandemic also significantly affected the lives of many. Any significant change in everyday routine induces stress and thus requires adaptational resources to deal with it. A recent review of the quarantine’s psychological effects concluded that people could suffer from mental disorders such as traumatic stress, low mood, and depression (Brooks et al., 2020).

To date, more than 400 studies have examined mental health issues in the global pandemic situation. There are systematic reviews on this topic, reporting that the risk of mental disorders increased significantly compared to the pre-outbreak period (Rajkumar, 2020). However, one study reported no significant changes in anxiety, depression, and stress indicators at different stages of the ongoing epidemic. The rates were the same early in the epidemic process, when the number of cases was growing, and later, when the epidemic declined, and the number of people who had recovered prevailed. However, it should be kept in mind that the pandemic might have long-term effects, as was the case after previous massive epidemics (Peng et al., 2010).

We can point out two main groups of factors that have led to psychological changes and stress-reactions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The first group includes real risks of getting sick and people’s fears for their physical health and the health of their loved ones. Those fears are related to risk assessment. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, health risks were unpredictable and could not be calculated based on official information or personal experience. Later the number of cases worldwide increased significantly, several famous people became infected with COVID-19, and the media began to show patients with the disease. Along with the possible occurrence of cases among acquaintances, all of those factors probably increased the subjective perception of risk due to the availability heuristic (Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, 1982).

Later, most people experienced significant changes introduced to their daily lives due to the pandemic. An enforced “vacation” resulted in a decrease or even a complete loss of income; some people lost their jobs or businesses. Economic shocks tend to be detrimental to psychological well-being, causing mental disorders, and increasing anxiety and depression on their own (Catalano et al., 2011). A compelled reduction or sometimes complete cessation of social contacts and personal communication is also a considerable stress factor associated with negative consequences for mental health (Wang et al., 2017). The restriction of social contact reduces the possibility of social support in a difficult situation, increasing the psychological consequences (Taylor, 2011; Viseu et al., 2018). In addition to limited interpersonal communication, restrictions on public life made many people lose access to their usual hobbies and places of interest, such as sports, theaters, and concerts.

Health-related fear, a decrease in social support availability, and the absence of the usual recreational activities have increasingly placed demands on psychological stability and the ability to cope with stressful situations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Coping with stress is possible through various internal mental resources, such as hardiness and meaningfulness. Hardinessis a pattern of attitudes towards the world, the ability to actively engage in relationships with it in any circumstances, to find constructive and valuable aspects in what is happening (Maddi & Khoshaba, 2005). Meaningfulnessincludes experiencing one’s own life as meaningful and oneself as having control over it.

Hardiness has traditionally been viewed in the context of resilience to stress factors (Eschleman, Bowling, & Alarcon, 2010). For example, higher hardiness was associated with a lower level of perceived stress among rescuers (Jamal, Zahra, Yaseen, & Nasreen, 2017), and with lower posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in military personnel (Thomassen, Hystad, Johnsen, Johnsen, & Bartone, 2018). Hardiness here possibly acts as a buffer, mitigating the negative impact of other factors on stress levels. For example, in Malaysian undergraduate students, poor problem-solving was generally associated with stress, but this stress was lower in students with higher hardiness (Abdollahi et al., 2016).

Numerous studies have linked hardiness to depression. Police officers with higher hardiness levels showed lower depression scores than their less resilient colleagues (Allison et al., 2019). The same results were demonstrated for US National Guard soldiers who returned after a one-year deployment to Afghanistan (Bartone, & Homish, 2020).

Hardiness prevents the deterioration of psychological well-being in stressful situations and becomes a good predictor of performance. For example, cadets’ job performance was predicted by their hardiness levels (Maddi et al., 2017; Nordmo et al., 2020). It may also be a buffer that reduces negative impacts on productivity, such as poor sleep quality, which was also observed in the sample of naval cadets (Nordmo et al., 2020).

According to many studies (e.g., Park et al., 2020), the feeling of life’s meaningfulness is also a predictor of low levels of depression. The lack of a feeling of meaning in life is not just a consequence or correlate of depression, but rather a reason for its development and continuation (Goodman, Doorley, & Kashdan, 2018).

Higher meaningfulness in life is associated with lower levels of stress indicators as well (Allan, Douglass, Duffy, & McCarty, 2016; Wang, Koenig, Ma, & Al Shohaib, 2016; Park & Baumeister, 2017). Experiencing life as meaningful can protect from the negative impact of harmful events, such as war (Blackburn, & Owens, 2015; Currier, Holland, & Malott, 2015) or being a victim of sexual violence (Gross, Laws, Park, Hoff, & Hoffmire, 2019), by lowering stress disorder, depression, and suicidal thoughts. A recent review of the relationship between well-being and psychopathological symptoms found that meaningfulness contributed to greater resistance to emotional difficulties and traumatic events (Goodman et al., 2018).

Several studies also noted a connection between meaningfulness of life and lower levels of anxiety, including health-related anxiety (Yek, Olendzki, Kekecs, Patterson, & Elkins, 2017). For example, meaningfulness in life acts as a buffer between anxious feelings and experiential avoidance (unwillingness to remain in contact with aversive thoughts) (Kelso, Kashdan, Imamoğlu, & Ashraf, 2020).

This study aimed to assess how psychological well-being (the severity of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and the overall severity of psychopathological symptoms) changed in the situation of the COVID-19 pandemic and related everyday life changes. We also aimed to evaluate the role of several socio-demographic factors and individual characteristics (hardiness and meaningfulness) in the severity of psychopathological symptoms accompanying changes in the pandemic situation.

We hypothesized that high levels of hardiness and meaningfulnesswere associated with less severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, and the general symptomatic index (GSI) during the COVID-19 outbreak in Russia in the first half of 2020.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 949 voluntary respondents (76.7% female), aged 18–66 years (mean age 30.55, median age 27, standard deviation 11.03) who participated in anonymous online research (Google Forms). The invitations were shared via social networks and in news articles on specialized psychological resources. The questionnaires were preceded by an informed consent form describing the research, data storage and processing conditions, and other ethical considerations. Only the data from participants who gave their informed consent was stored and used for further analysis. The participants were able to submit an optional feedback request after completing the form and were later provided with personal feedback.

Materials

Questionnaires

-

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Steer, & Beck, 1997) in a Russian adaptation by Tarabrina (2001).

-

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) in a Russian adaptation by Tarabrina (2001).

-

The Symptom Check-list-90-R (SCL-90-R) (Derogatis, & Savitz, 1999) in a Russian adaptation by Tarabrina (2001).

-

Noetic Orientations Test (NOT) (Leontiev, 2000). The global scale of this questionnaire description is very similar to our understanding of meaningfulness, as discussed above. The general NOT score is the only measurement from this method that we used in the current analysis, and it will be referred to as “meaningfulness” later on.

-

Personal Views Survey III (PVS-III-R) (Maddi & Khoshaba, 2001) in a Russian adaptation by Leontiev and Rasskazova (2006).

-

A socio-demographic survey, which included questions on how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the respondents’ lives, their main fears associated with the pandemic, what precautionary measures were taken, etc.

Procedure

The data was gathered online via Google Forms from March 24 to May 15, 2020.

The study began at a time when the official statistics in Russia were reporting no more than 100 new cases of COVID-19 per day, but traveling outside the country was already restricted significantly. Russian citizens coming from abroad and vulnerable groups (older people and people with chronic diseases) were put on self-isolation or institutionally quarantined; universities received recommendations to use distance education.

The first milestone for this study was on March 25, when the first week of paid days off was announced in Russia due to the progressive spread of the coronavirus. By that time, our data had been gathered for more than 24 hours. This was the first time that epidemic measures affected most of the country’s population, and the spread of the infection exceeded 100 new cases per day.

The second milestone was on April 2, related to the official announcement that non-working days were extended until the end of April (nine days into our data collection process). However, most people suspected that this “vacation” would continue until the end of the regular Russian May holidays (May 1, May 2, and May 9). By this point, it was clear that the pandemic-related changes would be lasting and require corresponding lifestyle changes.

The third milestone was the beginning of the long period of obligatory self-isolation (April 6, 13 days after the start of the research). By that time, people county-wide were transitioning to the remote format of work and education and had begun to adapt to this new reality. The infection in the country reached 1,000 new cases per day.

We divided all the collected data into four intervals (periods) to assess the dynamics of psychological well-being over time:

-

Period I (P I): March 24 – March 25, 88 data sets.

-

Period II (P II): March 26 – April 2, 262 data sets.

-

Period III (P III): April 3 – April 6, 296 data sets.

-

Period IV (P IV): April 7 – May 15, 303 data sets.

Results

Not all the questionnaires and scales showed normal distribution of the results, which influenced the choice of statistical methods, explained below for each case.

Table 1presents the descriptive statistics for the total amount of the data sets and the four identified periods.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics by period

|

|

P I (n=88) |

P II (n=262) |

P III (n=296) |

P IV (n=303) |

Total (n=949) |

|||||

|

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

|

Meaningfulness (NOT) |

100.39 |

18.58 |

95.00 |

19.10 |

93.36 |

20.17 |

91.67 |

21.96 |

93.92 |

20.45 |

|

Hardiness (PSV III) |

78.48 |

20.87 |

76.43 |

20.24 |

74.72 |

20.79 |

71.80 |

23.10 |

74.61 |

21.50 |

|

Depression (BDI) |

10.15 |

8.95 |

11.18 |

8.98 |

12.69 |

9.77 |

12.89 |

10.19 |

12.10 |

9.65 |

|

Anxiety (BAI) |

5.33 |

9.12 |

8.19 |

8.37 |

10.10 |

9.64 |

10.16 |

10.34 |

9.15 |

9.60 |

|

GSI (SCL-90-R) |

0.56 |

0.53 |

0.57 |

0.51 |

0.68 |

0.54 |

0.73 |

0.63 |

0.65 |

0.56 |

Table 1 shows that all psychological distress indicators (anxiety, depression, and SCL’s general symptomatic index, GSI) increased over time. Hardiness and meaningfulness scores decreased through the time-periods.

ANOVA was used to verify the significance of those differences. Due to non-normal distribution of some results, the inequality of the groups and the inequality of intra-group variances, Welch’s test (Welch’s ANOVA) was used instead of Fisher’s ANOVA, as it showed the best robustness against all those data specifics (Delacre, Lakens, Mora & Leys, 2019). Multiple comparisons were made using Bonferroni correction (for hardiness and meaningfulness, as those scales had equal variances) and Tamhane’s T2 all-pairs comparison test for the remaining scales, which had different variances. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

ANOVA results

|

|

Sum of squares |

df |

Mean square |

Welch |

Sig. |

Post hoc |

|

|

NOT |

Between groups |

5616.019 |

3 |

1872.006 |

4.899 |

0.002 |

P III>P I |

|

Within groups |

390920.518 |

945 |

413.673 |

|

|

P IV>P I |

|

|

Total |

396536.537 |

948 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hardiness |

Between groups |

4585.720 |

3 |

1528.573 |

3.173 |

0.024 |

- |

|

Within groups |

433526.674 |

945 |

458.758 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

438112.394 |

948 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anxiety |

Between groups |

2103.416 |

3 |

701.139 |

8.096 |

0.000 |

P III>P I |

|

Within groups |

85194.635 |

945 |

90.153 |

|

|

P IV>P I |

|

|

Total |

87298.051 |

948 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Depression |

Between groups |

851.675 |

3 |

283.892 |

3.244 |

0.022 |

- |

|

Within groups |

87497.815 |

945 |

92.590 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

88349.490 |

948 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

GSI |

Between groups |

4.701 |

3 |

1.567 |

5.077 |

0.002 |

P IV>P II |

|

Within groups |

296.977 |

945 |

0.314 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

301.678 |

948 |

|

|

|

|

|

Thus, significant differences between the time-periods were only shown for anxiety, meaningfulness, and GSI.

Then, we calculated Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients to assess the relationships between the measured indicators. Non-parametric correlation was used due to the non-normal distribution of the data. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Correlations between scales

|

|

NOT |

Hardiness |

Depression |

Anxiety |

|

1. NOT |

- |

|

|

|

|

2. Hardiness (PSV III) |

0.793** |

- |

|

|

|

3. Depression (BDI) |

-0.568** |

-0.681** |

- |

|

|

4. Anxiety (BAI) |

-0.302** |

-0.410** |

0.590** |

- |

|

5. GSI (SCL-90-R) |

-0.457** |

-0.610** |

0.760** |

0.716** |

Note. ** p-value < 0.01; n = 949

As seen in Table 3, all indicators of symptom severity correlated negatively with hardiness and the NOT score.

Our next step was to build general linear models (GLM) for anxiety, depression, and GSI. Those models included the following factors: socio-demographic indicators, self-assessed fears, preferred sources of information, trust in different sources of information, hardiness, and meaningfulness. The last two were grouped into low, medium, and high scores, based on reference values obtained in Russian-sample adaptations of the questionnaires.

One of our assumptions was that hardiness and meaningfulness participated as adaptational resources in stressful situations, helping people to cope better with anxiety, depression, and other psychopathological symptoms. We expected that an increase in symptoms would be mitigated with higher rates of hardiness and meaningfulness over time. Therefore, the interaction of those factors with the time-periods was included in the model.

Table 4shows the resulting model for anxiety (BAI). Factors that did not have statistically significant effects were excluded from the model.

Table 4

General linear model for anxiety (BAI)

|

|

Sum of squares |

df |

Mean square |

F |

Sig. |

Partial Eta squared |

|

Corrected model |

22398.569 |

21 |

1066.599 |

15.235 |

0.000 |

0.257 |

|

Intercept |

14045.896 |

1 |

14045.896 |

200.626 |

0.000 |

0.178 |

|

Sex |

1010.192 |

1 |

1010.192 |

14.429 |

0.000 |

0.015 |

|

Chronic diseases |

1765.572 |

1 |

1765.572 |

25.219 |

0.000 |

0.026 |

|

Fear for own health |

2252.850 |

4 |

563.213 |

8.045 |

0.000 |

0.034 |

|

Fear for relatives’ health |

987.619 |

4 |

246.905 |

3.527 |

0.007 |

0.015 |

|

Hardiness (PSV III) |

5391.890 |

2 |

2695.945 |

38.508 |

0.000 |

0.077 |

|

Period |

1592.761 |

3 |

530.920 |

7.583 |

0.000 |

0.024 |

|

Hardiness × Period |

935.401 |

6 |

155.900 |

2.227 |

0.039 |

0.014 |

|

Error |

64899.481 |

927 |

70.010 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

166726.000 |

949 |

|

|

|

|

|

Corrected total |

87298.051 |

948 |

|

|

|

|

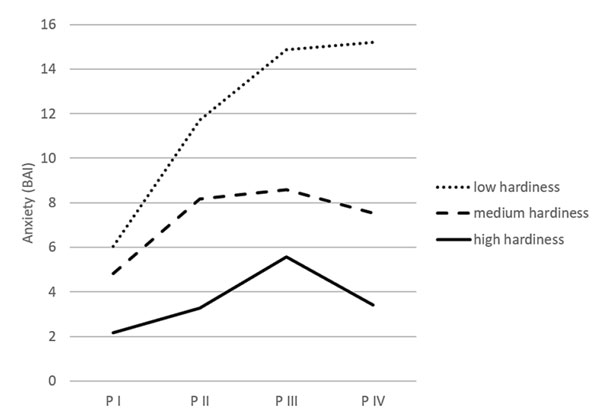

As shown in Table 4, anxiety levels varied depending on the participant’s sex, presence of chronic diseases, and declared fears for one’s health and the health of loved ones. Anxiety also increased over time. The most significant effect was observed from hardiness, while a statistically significant effect was observed from the interaction of hardiness and time-period (for better visual representation, see Figure 1). We failed to find a significant contribution of meaningfulness to the dynamics of anxiety in this model.

Figure 1. Interaction between hardiness and time in relation to anxiety

Figure 1 shows that individuals with a low level of hardiness were characterized by an increase in anxiety over the four observation periods. In people with medium or high hardiness, anxiety grew from the 1st to the 3rd periods, but fell during the 4th period.

The general linear model for depression is presented in Table 5.

Table 5

General linear model for depression (BDI)

| Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta squared |

Corrected model | 36324.638 | 20 | 1816.232 | 32.397 | 0.000 | 0.411 |

Intercept | 15689.805 | 1 | 15689.805 | 279.869 | 0.000 | 0.232 |

Sex | 449.901 | 1 | 449.901 | 8.025 | 0.005 | 0.009 |

Chronic diseases | 442.488 | 1 | 442.488 | 7.893 | 0.005 | 0.008 |

COVID-19 cases nearby | 436.358 | 1 | 436.358 | 7.784 | 0.005 | 0.008 |

Fear for relative’s health | 857.119 | 4 | 214.280 | 3.822 | 0.004 | 0.016 |

Socioeconomic fear | 986.463 | 4 | 246.616 | 4.399 | 0.002 | 0.019 |

Occupation | 644.443 | 3 | 214.814 | 3.832 | 0.010 | 0.012 |

Type of work | 433.275 | 2 | 216.638 | 3.864 | 0.021 | 0.008 |

Hardiness (PSV III) | 7985.785 | 2 | 3992.893 | 71.224 | 0.000 | 0.133 |

Meaningfulness (NOT) | 2456.727 | 2 | 1228.364 | 21.911 | 0.000 | 0.045 |

Error | 52024.852 | 928 | 56.061 |

|

|

|

Total | 227295.000 | 949 |

|

|

|

|

Corrected total | 88349.490 | 948 |

|

|

|

|

Women showed higher depression than men, and people with chronic diseases showed higher depression than those with no chronic illnesses. Respondents who lived in regions with reported cases of COVID-19 were also more likely to exhibit higher depression. Subjective fears for the health of relatives and fears that socio-economic conditions would worsen were also associated with the depression scores. Hardiness, as in the previous model, was shown to reduce the severity of depression, and a significant effect of meaningfulness was observed: It also decreased the symptoms of depression.

Occupation and regime of work (distance or other) played a significant role in the level of depression. For statistical data, see Table 6.

Table 6

Tukey’s range test results (multiple comparisons) for the regime of work and occupation

(I) | Mean difference (I-J) | Std. error | Sig. | 95% CI | ||

Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

L | W&L | 2.7510 | 1.01498 | 0.034 | 0.1388 | 5.3633 |

Regime of work R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SI/Q | 2.8327 | 0.85074 | 0.003 | 0.8356 | 4.8298 | |

| D | 1.9462 | 0.53396 | 0.001 | 0.6927 | 3.1996 |

Note. Occupation types: L – currently learning, W – currently working, W&L – currently working and learning, N – currently not working or learning; Regime of work: SI/Q – currently on self-isolation or quarantine, D – currently working or learning distantly, R – currently working or learning in usual format (non-distant). Only significant differences are listed.

Table 6 shows that higher rates of depression were seen in the participants whose main activity was learning (basically, non-working students), compared to those who were studying and working simultaneously. Those who were working full-time showed higher depression scores in comparison to those who were in quarantine and self-isolation or working from home.

Table 7 shows the general linear model for the GSI indicator of the SCL-90-R.

Table 7

General linear model for GSI (SCL-90-R)

| Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta squared |

Corrected model | 113.58 | 17 | 6.681 | 33.069 | 0.000 | 0.376 |

Intercept | 43.294 | 1 | 43.294 | 214.287 | 0.000 | 0.187 |

Sex | 3.482 | 1 | 3.482 | 17.235 | 0.000 | 0.018 |

Chronic diseases | 1.682 | 1 | 1.682 | 8.325 | 0.004 | 0.009 |

COVID-19 cases near | 1.796 | 1 | 1.796 | 8.890 | 0.003 | 0.009 |

Fear for own health | 3.698 | 4 | 0.924 | 4.575 | 0.001 | 0.019 |

Fear for relatives’ health | 2.834 | 4 | 0.709 | 3.507 | 0.007 | 0.015 |

Socioeconomic fear | 2.952 | 4 | 0.738 | 3.652 | 0.006 | 0.015 |

Hardiness (PSV III) | 74.371 | 2 | 37.185 | 184.050 | 0.000 | 0.283 |

Error | 188.098 | 931 | 0.202 |

|

|

|

Total | 708.378 | 949 |

|

|

|

|

Corrected total | 301.678 | 948 |

|

|

|

|

Women showed a higher general symptomatic index than men, and people with chronic diseases showed a higher GSI than those with no chronic illnesses. Respondents who lived in regions with reported cases of COVID-19 were also more likely to exhibit a higher general symptomatic index. Subjective fears (for one’s health, for the health of loved ones, of worsening socio-economic status) were positively associated with the general symptom severity index. Thus, the GSI in our sample behaved much like the depression score. Hardiness (as in the two previous models) demonstrated the most pronounced effect on the general symptom severity index. Meaningfulness showed no statistically significant effect in this model.

To assess the influence of biological sex, chronic diseases, and the presence of COVID-19 cases in the respondent’s region on the dynamics of the GSI, samples from the four periods were compared using the Chi-square test. There were no differences in the proportion of respondents with chronic diseases. There were more men in the samples of the second and third periods, and the largest share of respondents reporting the presence of COVID-19 cases in their region of residence was observed in the third period. Since men, on average, show less severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, and GSI than women, the observed increase of those indicators cannot be explained by sex only. As for the cases of COVID-19 in the respondent’s locality, the levels of depression and GSI in the third period did not significantly differ from other periods, and therefore the contribution of this factor to the dynamics of symptoms can also be discounted.

Discussion

The study showed that anxiety, depression, and the general severity of psychopathological symptoms were negatively correlated with meaningfulness and hardiness. These results are consistent with previous findings of negative correlations between hardiness and anxiety, hardiness and depression (Allison et al., 2019; Bartone, & Homish, 2020); meaningfulness and anxiety, meaningfulness and depression (Park et al., 2020; Yek et al., 2017), while both hardiness and meaningfulness were negatively correlated with mental health issues in general (Eschleman et al., 2010; Goodman et al., 2018).

All measurements were changing during the four periods of the COVID-19 pandemic reaction process in Russia. However, multiple comparisons showed statistically significant dynamics of meaningfulness, anxiety, and GSI only. Meaningfulness dynamics can be explained via the following example. An unforeseen, extremely unpredictable and stressful situation dramatically changes one’s everyday life, disrupts plans, and forces people to reconsider life goals and look for new ways to achieve them, to revise their views about life in general. The restrictive measures introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic put most people in challenging situations. Many had to learn new ways to carry out their professional activities; some could not work remotely and had to look for new sources of income. Thus, the emerging obstacles and general uncertainty about the future provoked anxiety and exacerbated existing problems, as evidenced by the increase in anxiety scores and the GSI.

As shown by general linear models, biological sex and chronic diseases were associated with higher scores in all three scales assessing the symptoms of psychological distress. The result seems predictable for people with chronic diseases, since they belong to the risk group for a severe COVID-19 scenario and consider the threat of infection higher. On the other hand, they faced restrictive measures earlier, and by the time they completed our survey, they had been self-isolating for an extended period. Women are generally known to be more susceptible to anxiety and depression (see, for example, Afifi, 2007; Rosenfield, & Mouzon, 2013). The severity of symptoms (GSI) varied for people declaring different levels of fears, related to both health and socio-economic status. The increase of health-related fears was associated with higher anxiety, depression, and the general severity of symptoms, while socio-economic fears were linked to depression and GSI. The negative correlation between the NOT scale and the levels of depression is also consistent with other studies (e.g., Goodman et al., 2018).

In our opinion, the most interesting finding of this study was the contribution of hardiness to the dynamics of anxiety. Higher hardiness rates were associated with a decrease in symptoms across all clinical scales. Simultaneously, the contribution of the hardiness indicator to the dynamics of anxiety over time was observed. People with lower hardiness showed anxiety increasing over time, while in people with medium to high hardiness, no significant rise in anxiety was found. That interesting dynamic could not be explained by hardiness changing over time, since no statistically significant differences were detected. These results confirm previously obtained data on hardiness as an adaptational resource under stress (Eschleman et al., 2010; Leontiev & Rasskazova, 2006; Maddi et al., 2017; Nordmo et al., 2020). However, meaningfulness did not impact the dynamics of psychological well-being, anxiety, depression, and general symptoms. Yet, higher meaningfulness in life was associated with less severe depression symptoms, with no apparent connection to the time factor.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic and preventive measures significantly changed the daily lives of many people in Russia. Our study showed that those changes were accompanied by an increase in anxiety, depression, and other mental disorders symptoms. However, the severity of psychopathological symptoms was found to be moderated by internal personal resources, with hardiness being the core one. Numerous studies have investigated hardiness as the main factor in stress resistance, and our results were consistent with the whole body of research. In people with higher hardiness, an increase in anxiety in response to stressful events was relatively short-term, about two to three weeks. The anxiety levels then dropped, in contrast to people with lower hardiness, in whom anxiety due to the pandemic and measures to curb it continued to increase after more than a month.

In further studies, we plan to assess the severity of post-stress disorder symptoms. According to the data available, the symptoms of that disorder would also be less pronounced in people with higher hardiness.

Limitations

Our sample turned out to be significantly biased towards the prevalence of female participants. More than 50 percent of the sample was under 30 years old, which also limited the possibility of generalizing the results. Most of the participants were residents of large cities (Moscow, Kazan, St. Petersburg). While this reduces the possibility of extrapolating the results to the entire population, it also allows a better assessment of the psychological consequences of the pandemic and pandemic-related restrictive measures, since more cases of COVID-19 occurred and more restrictions were applied in large cities.

Our conclusions about the dynamics of psychological well-being are preliminary, since the scheme used to assess them was not based on repeated measurements. However, the comparison of samples from different periods showed that differences in levels of anxiety, depression, and GSI could not be explained by side variables only.

References

Abdollahi, A., Abu Talib, M., Carlbring, P., Harvey, R., Yaacob, S.N., & Ismail, Z. (2016). Problem-solving skills and perceived stress among undergraduate students: The moderating role of hardiness. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(10), 1321–1331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316653265

Afifi, M. (2007). Gender differences in mental health. Singapore Medical Journal, 48(5), 385–391.

Allan, B.A., Douglass, R.P., Duffy, R.D., & McCarty, R.J. (2016). Meaningful work as a moderator of the relation between work stress and meaning in life. Journal of Career Assessment, 24(3), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072715599357

Allison, P., Mnatsakanova, A., McCanlies, E., Fekedulegn, D., Hartley, T.A., Andrew, M.E., & Violanti, J.M. (2019). Police stress and depressive symptoms: Role of coping and hardiness. Policing: An International Journal, 43(2), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-04-2019-0055

Bartone, P.T., & Homish, G.G. (2020). Influence of hardiness, avoidance coping, and combat exposure on depression in returning war veterans: A moderated-mediation study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 511–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.127

Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., & Brown, G.K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II.San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Blackburn, L., & Owens, G.P. (2015). The effect of self efficacy and meaning in life on posttraumatic stress disorder and depression severity among veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22133

Brooks, S.K., Webster, R.K., Smith, L.E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G.J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395 (10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Catalano, R., Goldman-Mellor, S., Saxton, K., Margerison-Zilko, C., Subbaraman, M., LeWinn, K., & Anderson, E. (2011). The health effects of economic decline. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 431–450. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101146

Currier, J.M., Holland, J.M., & Malott, J. (2015). Moral injury, meaning making, and mental health in returning veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22134

Delacre, M., Lakens, D., Mora, Y., & Leys, C. (2019). Taking parametric assumptions seriously: Arguments for the use of Welch’s F-test instead of the classical F-test in one-way ANOVA. International Review of Social Psychology, 32, 13. https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.198

Derogatis, L.R., & Savitz, K.L. (1999). The SCL-90-R, Brief Symptom Inventory, and matching clinical rating scales. In M.E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (pp. 679–724). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Eschleman, K.J., Bowling, N.A., & Alarcon, G.M. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of hardiness. International Journal of Stress Management,17(4), 277–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020476

Goodman, F.R., Doorley, J.D., & Kashdan, T.B. (2018). Well-being and psychopathology: A deep exploration into positive emotions, meaning and purpose in life, and social relationships. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being (pp. 471–495).Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers.

Gross, G.M., Laws, H., Park, C.L., Hoff, R., & Hoffmire, C.A. (2019). Meaning in life following deployment sexual trauma: Prediction of posttraumatic stress symptoms, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Research, 278, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.037

Jamal, Y., Zahra, S.T., Yaseen, F., & Nasreen, M. (2017). Coping strategies and hardiness as predictors of stress among rescue workers. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 32(1), 141–154.

Kahneman, D., Slovic, P. & Tversky, A. (Eds.). (1982). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases(1st ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kelso, K.C., Kashdan, T.B., Imamoğlu, A., & Ashraf, A. (2020). Meaning in life buffers the impact of experiential avoidance on anxiety. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 16, 192–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.04.009

Leontiev, D.A. (2000). Test smyslozhiznennyh orientacii (SZhO).[Noetic Orientations Test (NOT)], 2nd ed. Moscow: Smysl.

Leontiev, D.A., & Rasskazova, E.I. (2006). Test zhiznestoikosti.[Hardiness survey]. Moscow: Smysl.

Maddi, S.R., & Khoshaba, D.M. (2001). Personal Views Survey III-R: Internet instruction manual. Newport Beach, CA: Hardiness Institute.

Maddi, S.R., & Khoshaba, D.M. (2005). Resilience at work: How to succeed no matter what life throws at you. NY: AMACOM.

Maddi, S.R., Matthews, M.D., Kelly, D.R., Villarreal, B.J., Gundersen, K.K., & Savino, S.C. (2017). The continuing role of hardiness and grit on performance and retention in West Point cadets. Military Psychology, 29(5), 355–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/mil0000145

Nordmo, M., Olsen, O.K., Hetland, J., Espevik, R., Bakker, A.B., & Pallesen, S. (2020). It’s been a hard day’s night: A diary study on hardiness and reduced sleep quality among naval sailors. Personality and Individual Differences, 153 (109635), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109635

Park, C.L., Knott, C.L., Williams, R.M., Clark, E.M., Williams, B.R., & Schulz, E. (2020). Meaning in life predicts decreased depressive symptoms and increased positive affect over time but does not buffer stress effects in a national sample of African-Americans. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00212-9

Park, J., & Baumeister, R.F. (2017). Meaning in life and adjustment to daily stressors. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(4), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1209542

Peng, E.Y.C., Lee, M.B., Tsai, S.T., Yang, C.C., Morisky, D.E., Tsai, L.T., ... & Lyu, S.Y. (2010). Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: An example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 109(7), 524–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60087-3

Rajkumar R.P. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 52 (102066), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

Rosenfield, S., & Mouzon, D. (2013). Gender and mental health. In C.S. Aneshensel, J.C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 277–296). Dordrecht: Springer.

Steer, R.A., & Beck, A.T. (1997). Beck Anxiety Inventory. In C.P. Zalaquett & R.J. Wood (Eds.), Evaluating stress: A book of resources(pp. 23–40). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Education.

Tarabrina, N.V. (2001) Praktikum po psikhologii posttravmaticheskogo stressa. [Workshop on the psychology of posttraumatic stress]. St. Petersburg: Peter.

Taylor, S.E. (2011). Social support: A review. In H.S. Friedman (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 189–214). New York: Oxford University Press.

Thomassen, Å.G., Hystad, S.W., Johnsen, B.H., Johnsen, G.E., & Bartone, P.T. (2018). The effect of hardiness on PTSD symptoms: A prospective mediational approach. Military Psychology, 30(2), 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2018.1425065

Viseu, J., Leal, R., de Jesus, S.N., Pinto, P., Pechorro, P., & Greenglass, E. (2018). Relationship between economic stress factors and stress, anxiety, and depression: Moderating role of social support. Psychiatry Research, 268, 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.008

Wang, J., Lloyd-Evans, B., Giacco, D., Forsyth, R., Nebo, C., Mann, F., & Johnson, S. (2017). Social isolation in mental health: A conceptual and methodological review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(12), 1451–1461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1

Wang, Z., Koenig, H.G., Ma, H., & Al Shohaib, S. (2016). Religion, purpose in life, social support, and psychological distress in Chinese university students. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(3), 1055–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0184-0

Yek, M.H., Olendzki, N., Kekecs, Z., Patterson, V., & Elkins, G. (2017). Presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life and relationship to health anxiety. Psychological Reports, 120(3), 383–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117697084

To cite this article: Epishin, V.E., Salikhova, A.B., Bogacheva, N.V.*, Bogdanova, M.D., Kiseleva, M.G. (2020). Mental Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Hardiness and Meaningfulness Reduce Negative Effects on Psychological Well-Being. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 13(4), 75-88.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.