Psychological and legal aspects of the offensiveness of male and female cartoons and collages

Abstract

Background. This study addresses a current problem relating to trust and the identification of gender differences in trust/mistrust manifestation. Gender identity is associated with cultural stereotypes and social roles, which facilitate the formation of trust in people. It acts as a significant integral meaning-based component of an individual’s “I”- conception, which contributes to the formation of trust in himself and the world around him.

Objective. To study features of trust/mistrust towards others in young people with different gender identities.

Design. The cross-gender-typical sample consisted of 179 representatives, 83 males and 96 females, ages 17 to 23 (M = 19.34 and SD = 1.79). The techniques for collecting data included the MMPI, the Sex-Role Inventory by S. Bem, and the Trust/Mistrust towards Others questionnaire by A. Kupreychenko. The results were processed via the Mann-Whitney U Test, the Kruskal-Wallis H criterion, and cluster analysis.

Results. Criteria of trust/mistrust among the youth with different gender identities were identified, and basic types of trust — categoric, irrational–emotional, ambivalent– contradictory, and non-differentiated — were singled out. Irrespective of biological sex, bearers of different gender identities do not exhibit the same criteria to determine trust/ mistrust.

Conclusion. This study makes it possible to enrich our understanding of the role of social gender in the formation of interpersonal trust and differences in the foundations of trust toward others, in people with different gender identities. The empirical typology of trust in youth with different gender identities allows for using the typology in organizing psychological diagnostics, and for support and improvement of their interpersonal relations.

Received: 07.11.2015

Accepted: 30.03.2017

Themes: Social psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2017_2/psych_2_2017_10.pdf

Pages: 149-164

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2017.0210

Keywords: forensic, psychological, expert opinion, insult, cartoon, collage, politics, social status, gender

Introduction

Political caricatures have always been a means of political struggle. However, different methods of criticism through cartoons carry different psychological messages for an individual. The most socially acceptable cartoons are those that mock negative social phenomena or actions (Laskova & Zueva, 2016), whereas caricatures that deliberately insult a particular person do not receive any similar social approval as they violate the individuals legal right to honor and dignity. In Russia, such acts are prohibited by the Constitution. In literature sources, we have found some evidence that even friendly caricatures can be perceived as an insult to the person because they intentionally accentuate negative aspects of the persons appearance or character flaws (Emelyanov, 2011), which is perceived by a person as painful.

Various studies have made attempts to identify a list of offensive caricature techniques, but due to the delicacy of the topic, they analyzed mostly non-insulting caricatures or only slightly offensive drawings. For example, the analyzed caricatures of President Barack Obama showed him as a showman, an unlucky businessman, a drunkard, an old nag, etc. (Shustrova, 2014). The study of caricatures of President V. V. Putin was limited to the drawings that pictured him as a judo wrestler (Devyatkova, 2016). However, to protect the honor and dignity of an insulted person, it is necessary to identify a full list of offensive means and techniques.

The increased importance of the research aimed at the identification of the caricature and collage insult markers is caused by the social and political situation in the world, where caricatures and collages have become not only a means of political struggle but also a way of provoking ethnic, religious and state conflicts. In recent decades, the number of offensive methods and techniques has begun to grow. Therefore, the cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad (published in 2005, 2006 and 2014) led to serious unrest in the Muslim world. Similarly, the reaction of Russian society to the caricatures showing bomb explosions in the Moscow metro (2010) and the Sinai air crash (2015) was utterly negative. Russian media did not even reprint those pictures because for the Russian people their mere distribution was equivalent to a serious personal insult.

The attack on the editorial office of the French Charlie Hebdo on January 7, 2015 became a type of a psychological boundary that sharply increased the importance of research into insult marker identification and the impact of such markers on the person. That tragic event showed us all that caricatures can become a cause of a terrorist attack.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the purpose of political cartoons is to express editorial commentaries on politics, politicians and current events and to ensure the freedom of speech and of the press[1] According to this definition, political caricatures are not aimed at insulting a person. However, the reference to freedom of speech and the press denotes the general tendency of the Western media not to indicate the insult limits of the published cartoons and collages. Therefore, the public Paris demonstration to support Charlie Hebdo, apart from the call to speak out against terrorism collectively, contained an implicit appeal to defend the permissiveness of the press. It should be noted, however, that Charlie Hebdo caricatures published after the terrorist attack were considered purely outrageous by the public in many countries.

A.N. Baranov (2007) proposes that the evaluation of the abusiveness degree of non-verbal texts (including cartoons and collages) ought to be the subject of juridical psychological expert opinion. However, an evaluation cannot be carried out without a preliminary psychological analysis or without answering the question about how different people react to insulting pictures.

Some psychologists propose that most often, the most painful suffering of the insulted victim is caused by the indecency of a picture (Austin & Joseph, 1996). It was also found that the criteria of offensiveness depend upon sociocultural factors (Dov, Richard, & Bowdle, 1996). However, since the criteria of decency change with the development of society, one of the objectives of the present research has become the determination of pictures and their elements, which, in the consciousness of modern people, are particularly considered to be the most insulting images from the social point of view.

The topicality of the psychological research of abusiveness in cartoons and collages in Russia can be explained by the fact that comparatively recently (starting approximately since 1990) in the Russian press, one could often see caricatures of famous people: officials, politicians and others, which are insulting in their form and content. In scientific literature, this phenomenon later became known as “The Image War” (Churashova, 2012). Psychological and linguistic studies have researched the problem of identifying the medium (artistic mode) of offensive cartoons and collages (Medhurst & DeSousa, 1981, Shustrova, 2014). However, until now, there has been no research on the degree of offensiveness of different graphic tools and techniques.

When it became possible to take legal actions to have honor and dignity protected in connection with an insult by means of a cartoon or a collage, it was necessary for Russian court practice to have criteria with which to evaluate abusiveness in cartoons and collages.

M.S. Andrianov (2005) notes that a modern legal psychological expert must use subjective criteria if he has no objective criteria for the evaluation of the degree of abusiveness in cartoons and collages. The lack of objective criteria often results in the inability of psychological experts to convincingly prove the abusiveness of any given element of the picture.

There have not been any research studies devoted to the types of cartoons, collages and their elements that are insulting, the degree of their abusiveness for the honor and dignity of different sorts of personalities, what can be considered an indecent form of insulting, etc. The present psychological research is devoted to the settlement of these and other problems.

As some special terms will be used in the study, it is appropriate to give their definitions and to explain their meaning.

CARTOON is a picture in which a comic effect is created by the unity of some real and imagined facts, hyperbolizing and underlining some peculiar features, unexpected comparison and likening; it is the main pictorial form of satire.

CARICATURE is a humorous picture (usually a portrait) in which a persons peculiar features are emphasized and changed in a funny way though the resemblance is observable.

COLLAGE is a picture drawn by means of combining some fragments of different pictures; it is a sort of creative art work. The definitions show that cartoons and collages are a type of creative art work. Studies of cartoons in Russia are generally aimed at revealing artistic but not psychological aspects of such images (Belova & Shaklein, 2012). Therefore, very often when an artist or mass media that publishes the insulting cartoon or collage is called to account, they refer to the freedom of their creative work as an argument in their favor. However, the psychological research studies have demonstrated that while perceiving an art picture, a person not only has some aesthetic feelings but also realizes’ the author’s point of view on the depicted event or person. He also realizes an insulting emphasis that is placed by the author of the cartoon or collage (Anikina, 2013). It is clear that if the picture is aimed at insulting some personality, the depicted person has a feeling of insult, and not aesthetic feelings. The legal argument against using cartoons and collages with the purpose of insulting a personality is also meaningful. There is a general principle in the law: the freedom of one person (including his freedom of creating art works) comes to an end where the freedom of another person begins. Modern psychological studies in the field of cartoon perception show that the degree of their impact on individuals is determined by particular permutations of graphic methods (Mikhailova, 2011). Further research in this area has become the subject of our experimental study.

Method

Research objectives:

Evaluation of possible degrees of abusiveness in political cartoons and collages and determination of criteria with which to divide pictures into categories based on degrees of abusiveness.

Determination of gender aspects of the perception of political cartoons and collages.

Determination of the dependence of the perception of the abusiveness of a picture on the hierarchic status of the insulted person.

Reasoning for the research methods

The Method of Expert Opinion was chosen as the main method. It has been used in psychology for a long time. Another method used in this research was a psychological experiment. The necessity of an experiment can be explained by the peculiarities of the research material. The pilot research has demonstrated that when the participants were to evaluate the degree of the picture abusiveness for the person depicted in the cartoon or collage, they often did not solely assess the abusiveness of the form of some concrete picture but also the moral qualities of the person who became the object of the cartoon or collage. For example, if the participant did not like a politician, the expert found the picture of him less insulting even if it contained some elements of indecency. To avoid similar mistakes in perception, the participants were asked either to play the role of the depicted man’s solicitors or to imagine themselves in the place of his relatives or friends, or the insulted person, i.e., an element of role play was used. The results after the introduction of the experimental form became much more grounded.

Research hypotheses:

it is possible to single out some special elements of pictures that can make a political cartoon or collage insulting;

there are gender differences in the perception of female and male political cartoons and collages based on social stereotypes.

Description of the research methods

Participants. There were 120 participants in the study, 40 people of them took part in the first series, the rest of them were used in the second and third series. Age: 52 people were 20-25 years old, 36 people were 26-40 years old, and 32 people were 41-55 years old. Gender: 74 women, 46 men. Social status: 52 students, 16 workers, 5 businessmen, 47 representatives of the intelligentsia, executives of different ranks, 4 people who became the objects of the cartoons in mass media.

Research material. A total of 210 political cartoons and collages. All cartoons and collages were published in the world press.

Research methods. The Method of Expert Opinion and Experiment.

The statistical processing of the material was realized with the usage of the nonparametric Binominal Test.

The experiment was carried out in 3 parts.

Part 1 was conventionally called “the Kukryniksy”

The research tasks of part 1. 1) to single out the elements of pictures that make them insulting; 2) to arrange the elements of cartoons and collages due to the degree of their abusiveness.

While performing the research tasks of this part, the initial premise was the culturological data about the fact that in the former USSR, the use of purposeful insults in official papers was considered legal only for political purposes towards the enemies of the Motherland, traitors and state criminals. This fact helped to choose the experimental material. The participants were instructed to assess two groups of pictures. The first group consisted of the political cartoons drawn by the Kukryniksy from the series “The Enemy’s Face” and “The Enemies of the World”. All these pictures were created purposely to insult someone. Therefore, the material in this series became ideal in the process of the assessment of modern cartoons. The authors of modern cartoons and collages can deny the accusation of a purposeful insult by means of the picture created by them. However, the usage of some insulting elements of pictures typical of this culture can serve as an acknowledgment of the fact that the purpose was to humiliate the honor and dignity of the depicted person. There were 46 cartoons in this group.

Instructions for the participants. “What elements of cartoons are insulting for a person who became the object of the cartoon (collage)? Arrange (divide into groups) the cartoons and collages according to the degree of abusiveness of their elements”. After this work had been done, the participants were given an additional instruction only when the assessment of some certain pictures was vividly subjective: “Imagine that you have become a solicitor of the person depicted in the cartoon (collage) or you are his relative. How can you evaluate the degree of abusiveness in the cartoon now from these points of view?”

Part 2 was conventionally called “Male Cartoons and Collages”. It was necessary to analyze the cartoons and collages in which the main characters were male politicians.

Research tasks. 1) to determine the peculiarities of the modern language of insults by means of cartoons and collages; 2) to compare modern cartoons according to the degrees of abusiveness with the ideal criteria determined in Part 1; 3) to study how the prototypes of cartoons assess them.

Instruction for the participants. 1) The participants arranged the elements of modern political cartoons and collages according to the degree of abusiveness: “Will you please determine what elements of these pictures may make the person who became the object of the picture have equally strong emotions?” In addition, the participant was to include each of the cartoons (collages) into one of the groups generated in Part 1. 2) The second part of the instruction was only given to the participants who became the objects of cartoons themselves: “What elements of the cartoons where you are depicted do you dislike more and what ones less?”

Materials. The participants were shown all 150 modern political cartoons and collages in Part I divided into the corresponding groups according to the degree of abusiveness, the main characters of which were men.

Part 3 was conventionally called “Female Cartoons and Collages”. It was necessary to study the gender aspect of cartoons and collages. The participants were shown cartoons and collages in which the main characters were female politicians.

Research task. To determine if there is a difference in the perception of female cartoons by men and women.

Instructions for the participants. The same as in Part I.

Materials. A total of 14 cartoons and collages in which the main characters were female politicians.

Results and discussion

Results of Part 1 “The Kukryniksy”

All elements of the cartoons with a touch of abusiveness were characterized by most participants into 4 groups (see Table 1).

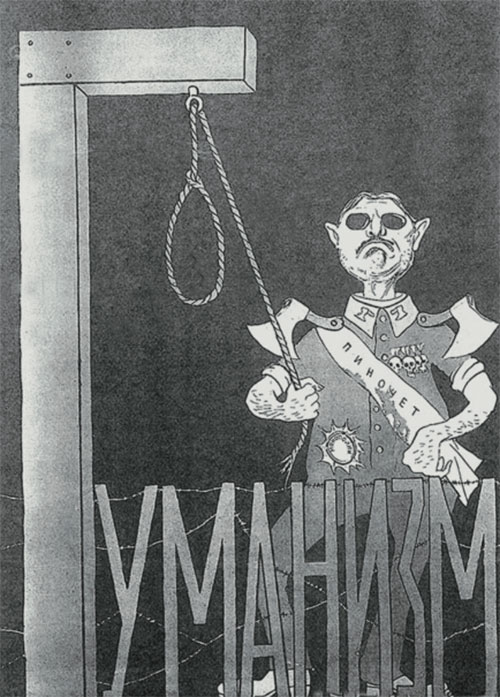

Thus, 95 % of the participants considered that the most insulting pictures were those in which a certain person is shown as a sadist, an executioner, etc. (e.g., see Fig. 1). Rather insulting images were those in which an image of a criminal was used (e.g., a thief) and the authors depicted some negative traits of character allegorically (greed, vanity, etc.) (75 % of the participants).

The pictures in which an emphasis was made on less attractive individual features of appearance of the insulted person were considered less insulting (e.g., brows, bald patch, etc.) (70% of the participants). As for the fourth group of elements, many participants (25 %) did not find them insulting, and the rest of the participants (75 %) proposed that under these conditions only people with certain individual peculiarities, e.g., those of character, temper, breeding, etc. could consider themselves insulted.

Table 1. Arrangement of cartoon elements according to the degree of their abusiveness (based on the material in Part 1 wThe Kukryniksy”).

| Group of pictures arranged according to the degree of abusiveness | Approximate characteristicsof insulting elements in pictures (Part I “The Kukryniksy”) | Number of participants who included the picture into this group (%) | Difference from the uniform distribution (χ2) |

| Group 1 — the most insulting elements of cartoons |

|

95 |

3.35

p<0.05 |

| Group 2 — rather insulting elements of cartoons |

|

75 |

0.178

p<0.05 |

| Group 3 — less insulting elements of cartoons |

|

70 |

0.97

p<0.05 |

| Group 4 — less significant (ambivalent) elements of cartoons |

|

75 |

0.178

p<0.05 |

The findings concerning the fourth group of elements are confirmed indirectly by our previous research (Budyakova, 2001). It has shown that there is a special group of verbal insults that are realized very specifically by a person who is the object of them. For example, when a person is ironically called some lofty names and he has ambivalent feelings, on the one hand, he should take offence at the irony, and on the other hand, he is compared with the acknowledged positive figures, for example, Cicero, Napoleon, etc. The quasi-victim is proud of the fact that he is placed in the same row with the similar people.

The elements placed into the fourth group in this series are of an ambivalent character. Thus, a picture of a tiger is a positive image of the zoomorphic character. In culturology this is a symbol of courage, strength, dexterity, etc. A touch of irony that can be seen in one of the caricatures (a lean mangy tiger) almost makes the image not insulting.

Figure 1. The Kukryniksy. The series “The Enemies of the World” (a cartoon of the Chilean Dictator Pinochet).

Results of Part 2 “Male Cartoons and Collages”

Table 2 shows how the elements of modern political cartoons and collages are distributed according to the degree of abusiveness. To the first group (the most insulting elements), in addition to the elements that were evaluated in Part I, the participants added some more obvious elements of obscenity present in modern political cartoons, depictions of private elements of life (e.g., functions of a human body), comparison with some odious people (Hitler, Himmler), etc. (98 % of the participants). The second group (rather insulting elements) contains zoomorphic images of a snake, allegoric images of a buffoon, a gofer, a Fascist, a whore, etc. (79 % of the participants). Less insulting elements were considered images of a persons head in the shape of a scalp, a beer mug, a branded sole, zoomorphic images of a monkey, a peacock, a crow, etc. (74% of the participants). The fourth group contains the elements of an ambivalent character, for example, the image of a shark is associated with a strong personality; the defenseless fish make the viewer like them (see Fig. 2).

The results of Part 1 and Part 2 led us to the conclusion that the number of insulting elements of pictures is not relatively large. It changes over the course of time (though not principally), when the social and political situation changes. Thus, an image of a snake was considered positive during the reign of the Russian Emperor Peter I, as it was a symbol of wisdom and immortality. A picture of a snake was stamped on the memorial medal issued on the occasion of Peter s death. At present, a visual image of a snake is an analog of the word “bastard”, i.e., it has a negative meaning. Insults of religious content typical of the past have practically disappeared from our everyday speech, except comparisons with Judas. A range of insulting elements has been enriched due to the consideration of some historic personalities or literary characters as odious figures, or vice versa. For example, Hitler and Himmler in the cartoons drawn by the Kukryniksy were the objects of insult, which was demonstrated in Part 1 of the present research, but at present the use of these images in pictures is a way of humiliating the honor and dignity of other people. On the contrary, in modern Mongolia, for example, Mamay and Batu Khan are considered national heroes, though quite recently they were regarded as negative historic personalities in the USSR.

Table 2. Arrangement of cartoon elements according to the degree of their abusiveness (based on the material of Part 2 “Male Cartoons and Collages”).

| Group of pictures arranged according to the degree of abusiveness | Approximate characteristics of insulting elements in pictures (Part 2 “Male Caricatures and Collages”) | Number of participants who included the picture in this group (%) |

Difference from the

uniform distribution

(X2) |

| Group 1 — the most insulting elements of cartoons |

|

94 |

7.83

p<0.05 |

| Group 2 — rather insulting elements of cartoons |

|

82 |

1.87

p<0.05 |

| Group 3 — less insulting elements of cartoons |

|

76 |

0.42

p<0.05 |

| Group 4 — less significant (ambivalent) elements of cartoons |

|

30 |

23.26

p<0.05 |

Note: The table contains only those elements that were determined in addition to the results of Part 1.

Figure 2. V. Putin pictured as a shark. Western leaders B. Obama, A. Merkel and E Oland shown as defenseless fish (http://dz-online.ru/article/2773/).

People with a different political orientation assess the same picture in a different way and this phenomenon of variable polarity has been revealed vividly in Part 2. In particular, neither of the participants considered that the leader of the Russian Communist Party, G.A. Zyuganov, was insulted in the collage in which he was drawn in the image of Lenin, although the caption under it mentioned the authors intention to humiliate him. Apparently, there is a factor of subjectivity in the process of forming negative personal figures (e.g., an image of an enemy) that was determined in Holstis research (Holsti, 1972).

During the evaluation of the results of Part 2, it was noted that the main tendency in modern caricature art is the intensification of an emphasis on forbidden intimate sides of a human life; these aspects were previously too obscene to reveal, even in cartoons of the enemies.

Some interesting data in Part 2 were found in the process of interviewing the participants who became the caricature objects. In general, their evaluation of their own cartoons approximately coincided with the evaluations that were provided by other participants. However, there was an essential difference. First, these people evaluated not the caricature content, but the attractiveness of their appearance. It is amazing that none of the other participants paid attention to this detail. In addition, this finding supports the research results of American psychologists, according to whom the factor of attractive appearance is important for both women and men (Aronson, 1995). Our study confirmed other researchers’ evidence on the existence of images that are considered ambivalent in terms of the ability to insult (Ulyanov & Chernyshov, 2015). Therefore, depictions of a person as a matryoshka (a small Russian doll encapsulating other dolls), a lion, or a bear were considered inoffensive despite the blatantly insulting context of the captions. Results of Part 3 “Female Cartoons and Collages”

The results are presented in Tables 3 and 4, and allow us to reveal the peculiarities in the evaluation of abusiveness of the cartoon elements concerning female politicians determined by both men and women. While analyzing the pictures, participants considered the most insulting elements those in which the only method of abusiveness was the depiction of a woman in an image of a pig or a monkey. This comparison aroused the associations that depicted a female politician as dirty, untidy, smelling bad, etc. It did not correspond with the cultural standards in the perception of a woman and aroused sharp indignation.

Table 3. Arrangement of political cartoons and collage elements according to the degree of their abusiveness made by the male participants (based on the material of Part 3 wFemale Cartoons and Collages”).

| Group of pictures arranged according to the degree of abusiveness | Approximate characteristics of insulting elements in pictures as determined by the male participants | Number of participants who included the picture in this group (%) |

| Group 1 — the most insulting elements of cartoons |

|

84 |

| Group 2 — rather insulting elements of cartoons |

|

76 |

| Group 3 — less insulting elements of cartoons |

|

76 |

| Group 4 — less significant (ambivalent) elements of cartoons |

|

84 |

According to the psychological literature, women are more sensitive to mockery than men (Radomska & Tomczak, 2010). It was also found that during gender identification, teenage girls tend to place more emphasis on image perception, asthey consider it very important to pursue certain images of their ideal role models while forming their own gender identities (Lopukhova, 2015). Special studies of cartoons that feature women revealed the most common methods of depicting women (Ivanova, 2013). However, our research has determined more differentiated criteria for womens perception of insults compared with men. The main difference in the analysis of pictures by the participants of a different gender was that the main indicator of abusiveness of the picture for women was an insult to their appearance. All cartoons in which a woman is drawn as ugly were placed in the group of the most insulting ones. Those pictures in which a woman looks attractive were evaluated as rather insulting. For example, images of a madwoman and a scarecrow were considered rather insulting concerning a motive because it was “a beautiful mad woman” and “a very nice scarecrow”. While evaluating these pictures, the men chose a different criterion: a correspondence of an image with the social stereotypes — a picture of an angry and irritated woman is bad not because her face becomes ugly but because she should be kind. The same concerns an image of a madwoman: it is insulting because a woman should be balanced.

Table 4. Arrangement of political cartoons and collages elements according to the degree of their abusiveness made by the female participants (based on the material of Part 3 “Female Cartoons and Collages”).

| Group of pictures arranged according to the degree of abusiveness | Approximate characteristics of insulting elements in pictures as determined by the female participants | Number of participants who included the picture in this group (%) |

| Group 1 — the most insulting elements of cartoons |

|

92 |

| Group 2 — rather insulting elements of cartoons |

|

84 |

| Group 3 — less insulting elements of cartoons |

|

80 |

| Group 4 — less significant (ambivalent) elements of cartoons |

|

92 |

The research has revealed some other differences in the perception of female political cartoons and collages. Thus, an image of a housewife was not considered insulting by the men. However, the women placed it in the group of less insulting pictures. This finding corresponds with the social stereotypes described in different research studies. From the point of view of the tested women, the fact that the female politicians who became cartoon objects pointed to their traditional place in the family and social life was an insult, but it was considered not very offensive due to the social conditions. In this respect, our study confirmed the data obtained by other researchers who believe that the correspondence of an image to sociocultural stereotypes, even if the latter are criticized, is considered ino ensive to women (Cro , Schmader, & Block, 2015). us, both groups of participants considered the image of Lithuanian President D. Grybauskaitė almost not o ensive. e image of “just a woman” with a typical feminine character is a sociocultural stereotype that does not cause any negative emotions (Fig. 3.).

Figure 3. The president of Lithuania Dalia Grybauskaite shown as a dim-witted woman with a strong personality (http:// politikus.ru).

Conclusion

All elements of the cartoons were divided into four groups according to the degree of abusiveness, which we have called: a) the most insulting picture elements, b) rather insulting ones, c) less insulting ones, d) ambivalent ones in terms of abusiveness. The most insulting elements were present in all images of obscene content and in images in which the authors compared people with some odious personalities: Judas, Hitler, etc. The rather insulting images were considered those of transvestites, criminals, etc. The less insulting images were caricatures and collages in which an emphasis was placed on some defects of appearance or on age, problems with health, etc. Ambivalent elements were those not usually considered by a person as insulting, but in a number of cases they are regarded as a peculiar compliment. For instance, comparing an individual with some famous historic personalities (Admiral Nelson, Napoleon and others), positive characters of folk epic literature (matreshka, a bear, FrogPrincess, etc.)

We have determined the difference in the criteria of evaluation of male and female political cartoons. For female politicians, the most insulting images were considered those ones in which the subjects are drawn either obscenely or they look ugly. A male character presented in the same way was not regarded as the most insulting picture. In addition, drawing a woman in the image of a monkey or a pig turned out to be the most serious insult for a woman but it was generally not very important for a man.

The images that were considered by the experts to be most insulting can be regarded not only as obscene concerning the form but were also created with the purpose of insulting the depicted person.

Male politicians may be seriously affected because they are drawn ugly but social principles forbid a man to suffer because of his unattractive appearance. As a result, caricaturists who draw a male politician do not feel confused because when a man says that he considers himself insulted in this respect, it harms his political authority. Additionally, when a certain insulted person has his subjective sufferings, it makes interpersonal relations with the person who was allowed to publish the ugly picture strained and unconstructive.

Further study of the assessment of the offensive impact of cartoon and collage elements, in our opinion, should be directed towards the compilation of detailed sets and syntaxes of graphic tools that have a certain psychological impact on the person and their ranking according to their degree of offensiveness. This will help courts make fair judgments in lawsuits concerning the honor and dignity of people in cases of abuse by means of cartoons and collages.

Limitations

Our study has certain limitations. e investigation of the way cartoons and collages influence individuals was carried out without taking into consideration any ethnographic perception peculiarities of the representatives of different cultures. All participants were Russian. Therefore, the expert assessment of the way an image influences the honor and dignity of the representative of a different (non-Russian) nationality may not be based on the reported data only and requires further study and explanation.

References

Andrianov, M.S. (2005). Problema ekspertnoi otsenki smyslovoi napravlennosti neverbalnykh komponentov kommunikatsii, stavshikh predmetom sudebnykh razbiratelstv [ The problem of expert evaluation of meaning purposefulness of communication nonverbal components that became the subject of trials]. Materialy konferentsii po yuridicheskoi psikhologii, posvyashchennoi pamyati M.M. Kochenova [Proceedings of the conference on legal psychology, dedicated to the memory M.M Kochenov]. Moscow: Мoscow State University of Psychology and Education.

Anikina, V.G. (2013). “Veshch iskusstva” kak znakovyi objekt re eksii [“A thing of art” as the sign object of reflection]. Psikhologicheskii zhurnal [Psychological Journal], 6, 26–35.

Aronson, E. (1995). The social animal. New York: W.H. Freeman & Co.

Austin, S., & Joseph, S. (1996). Assessment of fully victim problems in 8-10 years-olds. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 66(4), 447–456. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1996. tb01211.x

Baranov, A.N. (2007). Lingvisticheskaya ekspertiza teksta [Linguistic examination of a text]. Moscow: Flinta.

Belova, M.A., & Shaklein, V.M. (2012). Lingvokulturologicheskii analiz tekstov karikatur [Linguistic and culturological analysis of caricature texts]. Vestnik Rossiiskogo universiteta druzhby narodov [Bulletin of Russian Peoples’ Friendship University], 2, 19–24.

Budyakova, T.P. (2001). Pravovaya i lingvisticheskaya otsenka vyskazyvanii s tochki zreniya ikh vliyaniya na chevstvo dostoinstva cheloveka [Legal and psychological evaluation of expressions from the point of view concerning their in uence on a person’s self-respect]. Materialy Vserossiiskoi nauchnoi konferentsii “Problemy izucheniya i prepodavaniya yazyka” [Proceedings of the Russian scientifc conference “ e problems of studying and teaching a language”]. Yelets, Russia: Yelets Bunin State University.

Churashova, E.А. (2012). Rossiisko-gruzinskii kon ikt v karikaturakh: Analiz obvinitelnogo diskursa zapadnykh karikatur [Russian-Georgian con ict in pictures: Analysis of accusatory discourse of western caricatures]. Vestnik NGUEU [NGUEU Bulletin], 2, 191–199.

Croft, A., Schmader, T., & Block, K. (2015). An underexamined inequality: Cultural and psychological barriers to men’s engagement with communal roles. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19, 343–370.

Devyatkova, М.I. (2016). Lingvokulturnye tipazhi “Dzyudoist” i “Borets” (na materiale russkikh politicheskikh karikatur s obrazom Vladimira Putina) [Linguo-cultural types of “Judoist” and “Wrestler” (based on Russian political cartoons of Vladimir Putin)]. Lingvokulturologiya [Linguistic Culturology], 10, 110–122.

Dov, D., Richard, E., & Bowdle, B. (1996). Insult, agression, and the southern culture of honor: An “experimental ethnography”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 945–960.

Emelyanov, V.A. (2011). Karikatura kak priem (utrirovannye obrazy A. Remizova) [Caricature as a reception (exaggerated images of A. Remizov)]. Gumanitarnye issledovaniya [Humanitarian research], 4, 218–224.

Holsti, O.R. (1972). Enemies are those whom we de ne as such: A case study. In I. Duchacek (Ed.), Discord and harmony: Reading in international politics. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Ivanova, E.N. (2013). Zhenshchina v rossiiskoi politicheskoi karikature [Women in the Russian political cartoons]. Zhenshchina v rossiiskom obshchestve [Woman in Russian Society], 3(68), 66–78.

Laskova, M.V., & Zueva, R.S. (2016). Politicheskaya karikatura kak sotsial’no-kul’turnaya universaliya v sovremennoi politicheskoi lingvistike [Political caricature as a social and cultural universal in modern political linguistics]. Gumanitarnye i sotsialnye nauki [Humanities and Social Sciences], 1, 71–75.

Medhurst, M.J., & DeSousa, M.A. (1981). Political cartoons as a rhetorical form: A taxonomy of graphic discourse. Communication Monographs, 48, 197–236. doi: 10.1080/ 03637758109376059

Mikhailova, Y. (2011). Premyer-ministr Koidzumi Dzyunitiro v politicheskoi karikature — k voprosu ob osobennostyakh sovremennoi yaponskoi karikatury [Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro in political cartoons: On characteristic features of contemporary Japanese cartoons]. Pismennije pamyatniki vostoka [Written Monuments of the Orient], 1, 161–178.

Lopukhova, O.G. (2015). The impact of gender images in commercials on the self-consciousness of adolescents. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 8(1), 100–111. doi: 10.11621/ pir.2015.0109

Radomska, A., & Tomczak, J. (2010). Gelotophobia, self-presentation styles, and psychological gender. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 55(2), 191–201.

Shustrova, E.V. (2014). Barak Obama: neuteshitelnye itogi leta 2014 v amerikanskoi karikature [Barak Obama: Disappointing results of summer 2014 in American cartoons]. In Politicheskaya kommunikatsiya: perspektivy razvitiya nauchnogo napravleniya. Materialy mezhdunarodnoi nauchnoi konferentsii [Political communication: the prospects of development of scientific directions. Proceedings of the International scientific conference]. (p. 279). Yekaterinburg: Ural State Pedagogical University.

Ulyanov, P.V., & Chernyshov, Y.G. (2015). Rossiya v ambivalentnom “obraze medvedya” (na primere evropeiskikh karikatur perioda pervoi mirovoi voiny) [Russia in the ambivalent “image of the bear” (on the example of European caricature of the First World War)]. Izvestiya Altaiskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta [Altai State University Bulletin], 4(88), 259–265.

Notes

1. https://www.britannica.com/topic/political-cartoon

To cite this article: Budyakova T. P. (2017). Psychological and legal aspects of the offensiveness of male and female cartoons and collages. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 10(2), 149-164.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.