Assimilation or integration: Similarities and differences between acculturation attitudes of migrants from Central Asia and Russians in Central Russia

Abstract

When acculturation strategies of migrants and acculturation expectations of a host society do not coincide, psychological outcomes for members of the groups in contact can differ significantly. Berry (2013) proposed that intercultural relations can be understood on the basis of three hypotheses: the multiculturalism hypothesis, the integration hypothesis, and the contact hypothesis. Our goal was to test these three hypotheses in Russian majority and Asian minority groups. Migrants from Central Asia (N = 168; 88 ethnic Uzbeks and 80 ethnic Tajiks) and ethnic Russians (N = 158) were surveyed using a self-report questionnaire that included measures developed by the Mutual Intercultural Relations in Plural Societies project. Data processing was carried out using Structural Equation Modeling with the Russians and the migrants separately. We found significant and positive relationships between perceived security and multicultural ideology in both groups. We found a positive relationship between intercultural contacts and the integration strategy among the migrants from Central Asia. Intercultural contacts in the group of Russians was positively related to the expectation of integration and negatively related to the expectation of assimilation. The integration strategy of the migrants was positively related to their self-esteem, while the assimilation strategy was positively related to their sociocultural adaptation and life satisfaction. Among the Russians, the integration expectation promoted their better life satisfaction and self-esteem. The multiculturalism hypothesis was partially supported with both the migrants from Central Asia and the Russians: perceived security promoted an acceptance of multicultural ideology but didn’t promote ethnic tolerance. The contact hypothesis was partially supported in both groups: interethnic contacts were positively linked to the integration strategy of the migrants and the integration expectations of the Russians. The integration hypothesis was fully supported in the sample of Russians and partially supported in the sample of migrants. The migrants’ adoption of the assimilation strategy promoted their life satisfaction and sociocultural adaptation.

Received: 11.11.2015

Accepted: 20.01.2016

Themes: Multiculturalism and intercultural relations: Comparative analysis; Psychology of ethno-cultural issues

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2016_1/psychology_2016_1_7.pdf

Pages: 98-111

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2016.0107

Keywords: acculturation, adaptation, assimilation, integration, intercultural relations, multiculturalism, well-being

Introduction

Mutuality in the acculturation strategies of ethnic minorities and the acculturation expectations of majorities is a source of successful adaptation and favorable intercultural relations. However, many factors have an impact on acculturation and mutual adaptation, such as length of residence, cultural distance, language proficiency of migrants, their professional skills, their education, the economic and political situation in the country, and its migration policy. In our study we were interested in possible discrepancies between the acculturation strategies of migrants and the acculturation expectations of the host population and in any consequences of these discrepancies.

The percentage of immigrants from Central Asian countries less economically developed than Russia (such as Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) grew up from 24.4% in 2000–2004 to 40.4% in 2010–2013. Russia’s attractiveness for migration from post-Soviet Central Asia is determined by a common history and widespread Russian language usage in interpersonal communication during the Soviet period. Additionally, the visa-free regime between Russia and these countries facilitates movement across borders. The number of migrants from Uzbekistan working in Russia was estimated at 399,000 in 2011, and the estimate for migrants from Tajikistan was 166,000. These constitute the largest migrant-labor groups in Russia; members of these groups see migration to Russia as a strategy for success in life. The decision to migrate is reinforced by the experience of those who have already emigrated and who have been able to improve the financial situation of their families (Di Bartolomeo, Makaryan, & Weinar, 2014). Ryazantsev and Korneev (2014), after analyzing the migration situation, concluded that it constituted a new social phenomenon: “Sustainable life strategies among the Central Asian population . . . focus on success exclusively through labor migration” (p. 13).

Despite the fact that migration from these countries to Russia began in the early 1990s, difficulties in the mutual adaptation of the host population and the migrants have not disappeared. When this migration started, the main flow of migrants was mostly ethnic Russians or Russian speakers who returned to Russia after the collapse of Soviet Union. However, since the end of the 1990s the structure of migration has changed. At present, many of the migrants are natives of the Central Asian countries. Although these migrants include students, small businessmen, and well-educated and highly qualified people, the main migration flow from Central Asia is migrant workers. Low wages and high unemployment rates, especially among the rural population in Central Asia, serve as powerful push factors for young and frequently less skilled migrants who do not speak Russian and who are thus often perceived as culturally and socially distant by the host population in Russia (Di Bartolomeo et al., 2014; Zayonchkovskaya & Tiuriukanova, 2010). Researchers emphasize the crucial role of perceived cultural and social distance in shaping attitudes toward Central Asian migrants (e.g., Abashin, 2013; Zayonchkovskaya, Poletaev, Doronina, Mkrtchyan, & Florinskaya, 2014).

Muscovites increasingly perceive migration as a threat to their cultural security. The causes for perceived insecurity include: patterns of behavior that do not meet local cultural norms; the deterioration of health and the epidemiological situation; a reduction in the level of education in schools as a result of migrants’ children having poor knowledge of the Russian language; the existence of “rubber apartments” (a term that refers either to apartments where hundreds of people are fictitiously registered but do not live or to apartments that house large numbers of migrants in a small area), which worsen general living conditions; the involvement of migrants in crimes; and the saturation of the labor market. Despite the presence of migrants from many other regions and countries, Muscovites consider migrants from Central Asia as the most problematic and risky groups. In turn, migrants face problems with registration, finding housing and legal employment, accessing medical services, enrolling children in school, and corruption (Zayonchkovskaya et al., 2014).

The aim of our study was to test three hypotheses of intercultural relations in the Russian majority and the Central Asian minority groups: the multiculturalism hypothesis, the contact hypothesis, and the integration hypothesis (Berry, 2013; Lebedeva, Tatarko, & Berry, 2015).

We chose to study the Central Federal District of Russia because this region attracts the highest number of migrants—approximately 43% of officially employed foreign workers in the region as a whole and 30% in Moscow (Di Bartolomeo et al., 2014).

Acculturation and adaptation

Acculturation is a result of intercultural contact. It involves changes on two levels:

(1) cultural changes in both groups and (2) behavioral or psychological changes in individuals. Berry (1990) proposed that the positive and negative orientations of migrants toward maintaining their heritage culture and toward contact with the host society could be combined in four different acculturation strategies: integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalization. Integration involves contact and identification with both cultures. Separation involves identification with only the culture of one’s heritage country and contacts with one’s own group members. Assimilation involves identification with the host country’s culture and nonacceptance of one’s heritage culture. Marginalization is the absence of identification with both cultures. These four strategies lead to different consequences on the individual level. Many studies have revealed variations in the adaptation of migrants across these four acculturation strategies (Berry & Sabatier, 2010, 2011; Nguyen & Benet-Martínez, 2013; Ward, 2008). Integration is usually associated with the best adaptation, while marginalization results in the least successful psychological and sociocultural adaptation and intergroup relations.

The acculturation expectations of members of the larger society are defined by the same two dimensions as migrants’ acculturation strategies (Berry, 1990). The integration expectation of the majority group is associated with more positive psychological outcomes and favorable intergroup attitudes. The role of the dominant group in the acculturation process of migrants and minorities is important. The acculturation expectations of members of the larger society have an impact on how intergroup relations develop even more than the attitudes of members of the minority groups because the majority group has greater access to resources and influence, and the involvement of this group in the public and political life of the state has a longer history and therefore is stronger (Geschke, Mummendey, Kessler, & Funke, 2010).

Previous studies have revealed that the relationship between acculturation strategies and adaptation is strongly influenced by the social and political context of the receiving society (Berry & Sabatier, 2010; Jasinskaja-Lahti, Liebkind, Horenczyk, & Schmitz, 2003; Kus-Harbord & Ward, 2015) as well as by the duration of migrants’ residence in the host country (Jasinskaja-Lahti, Horenczyk & Kinunen, 2011). Additionally there are differences between psychological and sociocultural adaptation (Masgoret & Ward 2006) and differences in the relationships between different acculturation strategies and kinds of adaptation. Ward and Rana-Deuba (1999) found that integration predicted psychological adaptation, while assimilation better predicted sociocultural adaptation. The study of Jasinskaja-Lahti and colleagues (2011) confirmed the positive impact of integration on psychological adaptation but not on socioeconomic adaptation. In the same study, length of residence in the host country predicted sociocultural and socioeconomic adaptation but not psychological adaptation. The researchers concluded that integration as well as assimilation might promote socioeconomic adaptation in culturally diverse countries at the beginning of the acculturation process. We believe that the relationship between different acculturation strategies/expectations and the different types of adaptation requires additional studies in different contexts and with different ethnic groups.

The research hypotheses

According to Berry (2013) three hypotheses (the multiculturalism hypothesis, the contact hypothesis, and the integration hypothesis) are crucial for understanding intercultural relations. The multiculturalism hypothesis connects individuals’ perceived security to their acceptance of those who are culturally different. The contact hypothesis proposes that contact with individuals from other groups promotes positive intercultural attitudes (it is important that the contact be equal and voluntary). The integration hypothesis proposes that double cultural engagement (integration of both cultures) promotes psychological and sociocultural adaptation. For our study, we formulated the following hypotheses:

- The multiculturalism hypothesis: the higher a person’s sense of security, the higher the willingness to accept those who are culturally different. Specifically: the higher the perceived security, the higher the support of multicultural ideology and ethnic tolerance (for both the immigrant group and members of the larger society).

- The contact hypothesis: intercultural contact and sharing promote mutual acceptance (under certain conditions, especially that of equality). Specifically:

2a. The higher the intensity of friendly contacts with the larger society among immigrants, the higher their preference for integration or assimilation strategies.

2b. The higher the intensity of friendly contacts with immigrants among members of the larger society, the higher their level of ethnic tolerance and their preferences for integration or assimilation expectations. - The integration hypothesis: the higher one’s preference for the integration strategy, the higher one’s psychological and sociocultural adaptation. Specifically:

3a. The higher the preference for the acculturation strategy of integration among immigrants, the higher their level of life satisfaction, self-esteem, and sociocultural adaptation.

3b. The higher the preference for integration expectation among members of the larger society, the higher their level of life satisfaction and self-esteem.

Method

This study was conducted in the Central Federal District of Russia among 158 ethnic Russians and 168 migrants from Central Asia (80 ethnic Tajiks and 88 ethnic Uzbeks). Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

|

Group |

N |

Gender |

Age |

||||

|

Male |

% |

Female |

% |

Range |

M |

||

|

Russians |

158 |

34 |

21.52 |

124 |

78.48 |

19–69 |

42 |

|

Migrants |

168 |

103 |

61.31 |

65 |

38.69 |

19–66 |

30 |

Participants were surveyed using a self-report questionnaire. For migrants the questionnaire was translated into Uzbek and Tajik (translation and back translation were used). The data of migrants were collected using a snowball sampling procedure in Federal Migration Service Centers, markets with migrant workers, and universities. All participants were informed that participation was voluntary and that their responses were anonymous. The questionnaires contained demographic questions and measures developed in the Mutual Intercultural Relations in Plural Societies (MIRIPS) project. The items were translated into Russian and adapted for use in previous studies (Lebedeva & Tatarko, 2009). The complete MIRIPS questionnaire is available on the project website: http://www.victoria.ac.nz/cacr/ research/mirips.

Measures

Most of the answers to questions were given on a scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The scales were formed by averaging their corresponding items.

Perceived security. This scale included five items (αRussians =. 51; αmigrants =.60) related to perceptions of threat/security in various fields: culture (e.g., “There is room for a variety of languages and cultures in this country, ” “We have to take steps to protect our cultural traditions from outside influences”; these were for the threat questions and were reversed for the security questions), economics (e.g., “The high level of unemployment presents a grave cause for concern”; this question was reversed), everyday life (e.g., “A person’s chances of living a safe, untroubled life are better today than ever before”).

Intercultural contacts. Intercultural contacts were measured by tallying the number of Russian close friends for migrants (e.g., “How many close Russian friends do you have?”) or the number of close friends from other ethnic groups for Russians, and, for both groups, the frequency of contact with these friends (e.g., “How often do you meet with close [Russian] friends?” The responses on the first item ranged from 1 (“none”) to 5 (“many”), and on the second one they varied from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“daily”). Cronbach’s alphas were .91 and .76 for Russians and migrants, respectively.

Tolerance. The tolerance scale measured the degree of acceptance of culturally different individuals or groups. We used three items (αRussians = . 67; αmigrants = .56) (e.g., “It is a bad idea for people of different races/ethnicities to marry one another”; this question was reversed).

Multicultural ideology. This scale consisted of four items (αRussians = .75; αmigrants = .67). It measured the degree of acceptance and positive assessment of cultural diversity and participation (e.g., “A society that has a variety of ethnic and cultural groups is more able to tackle new problems as they occur”).

Acculturation strategies of migrants/acculturation expectations of Russians. The integration strategies of migrants and the integration expectations of Russians were assessed with four items (e.g., “I feel that Uzbeks/Tajiks should maintain our own cultural traditions but also adopt those of Russians,” “I feel that migrants should maintain their own cultural traditions but also adopt those of Russians”). Cronbach’s alphas were .75 and .70 for Russians and migrants, respectively. The assimilation strategies of migrants and the respective assimilation expectations of Russians were assessed with four parallel items also (e.g., “I feel that Uzbeks/Tajiks should adopt Russian cultural traditions and not maintain our own,” “I feel that migrants should adopt Russian cultural traditions and not maintain their own”). Cronbach’s alphas were .71 and .68 for Russians and migrants, respectively.

Self-esteem. This scale consisted of four items (αRussians = . 80; αmigrants = .73) from Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) (e.g., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself,” “I am able to do things as well as most other people”).

Life satisfaction. We used four items (α Russians = . 69; α migrants = .76) from the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) (e.g., “So far I have got the important things I want in life”).

Sociocultural adaptation. This scale was used for the migrant sample only. It included 10 items from the Revised Sociocultural Adaptation Scale (Wilson, 2013) (α migrants = . 94). The items measured respondents’ self-ratings of difficulties in different social domains: for example, community involvement, personal interests, religion, communication.

Russian-language proficiency. Proficiency was measured by four items (“How well do you understand/speak/read/write Russian?”) (αmigrants = . 89).

Demographic variables. Ages of respondents and duration of residence of migrants in Russia were measured in years.

Data processing

To test the predicted model with the three hypotheses we followed a Structural Equation Modeling approach (Kline, 1998). Two path analyses were performed using SPSS AMOS 20 software (Arbuckle, 2011) with the Russian and the migrant samples separately.

Results

The migrants’ average duration of residence in Russia was 5.81 years (SD = 4.55). The majority of respondents (60.1%) arrived in Russia in the previous 5 years, and less than half (39.9%) arrived in the previous 3 years.

The mean of the Russian-language proficiency of the migrants was sufficiently high despite the fact that they completed their questionnaires in their native language: 3.88 (SD = .84).

The mean of the integration preferences of the migrants was significantly higher than the mean of the integration expectations of the Russians (t = –5.23, p < .001). The means of intercultural contacts and perceived security were also significantly higher in the group of migrants (t = –9.25, p < .001 for contacts, and t = –3.08, p < .01 for security). The two groups did not differ in life satisfaction, but we found differences in the level of self-esteem, which was higher among the migrants (t = –3.54, p < .001).

The descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation coefficients for the variables used in the study among Russians (N = 158) and migrants (N = 168). Note: Migrants/Russians. *p < .05. **p < .01.

|

|

Pearson’s r |

||||||||||

|

Measures |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

Perceived security |

3.94/ 3.70 |

.79/ .63 |

1 |

.24**/-.11 |

.21**/.34** |

-.02/ .10 |

.08/ .01 |

.16*/ .12 |

.16* / .12 |

.22*/ .16* |

.08 |

|

Contacts |

3.18/ 2.07 |

1.05/ 1.12 |

|

1 |

.15 / .11 |

.16*/ .02 |

-.06 /-20* |

.18*/ .23** |

.21*/ .14 |

-.01/ -.02 |

-.11 |

|

Multicultural ideology |

4.09/ 3.94 |

.79/ .70 |

|

|

1 |

.10/ .57** |

-.14/ -.42** |

.30**/ .39** |

.25**/ .15 |

-.08/ .05 |

-.12 |

|

Ethnic tolerance |

3.35/ 3.13 |

1.15/ 1.05 |

|

|

|

1 |

-.19*/ -.40** |

.10/ .20* |

.23**/ .07 |

-.09/ .09 |

-.16* |

|

Assimilation |

2.18/ 2.04 |

1.00/ .73 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

-.21*/ -.09 |

-.14/ -.13 |

.31**/ .05 |

.21** |

|

Integration |

4.39/ 3.95 |

.83/ .68 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

.23**/ .20* |

-.04/ .19* |

-.06 |

|

Self-esteem |

4.36/ 4.10 |

.77/ .49 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

.37**/ .25* |

-.03 |

|

Life satisfaction |

3.28/ 3.23 |

1.11/ .78 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

.28** |

|

Sociocultural adaptation |

2.49 |

1.20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

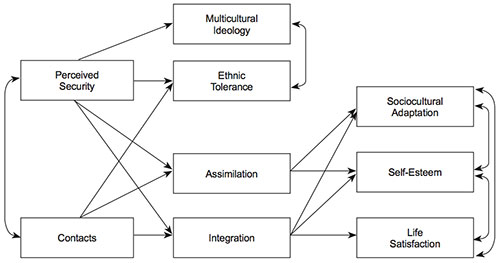

Figure 1. The tested model

The tested model is presented in the Figure 1. Sociocultural adaptation was used in the group of migrants only.

Standardized regression coefficients for the empirical model for the group of migrants are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Standardized regression coefficients for the empirical model for the group of migrants. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

|

|

Dependent variables | ||||||

| Predictors | Multicultural ideology | Ethnic tolerance | Assimilation | Integration | Self-esteem | Life satisfaction | Sociocultural adaptation |

| Perceived security | .27** | -.04 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Contacts | - | .13 | -.06 | .16* | - | - | - |

| Assimilation | - | - | - | - | -.07 | .31*** | .20** |

| Integration | - | - | - | - | .19* | .02 | -.02 |

| R2 | .03 | .02 | .00 | .03 | .04 | .10 |

.04

|

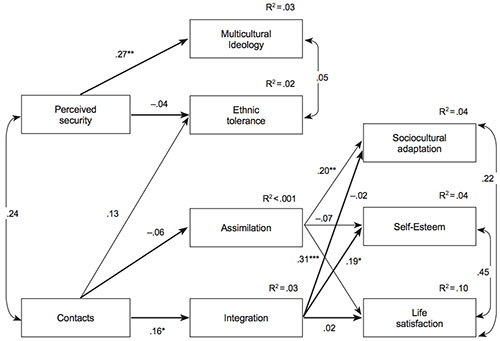

The empirical model for the group of migrants is presented in Figure 2. Goodness-of-fit indicators of the model for migrants were satisfactory (χ2 = 30.53, df = 16, χ2/df = 1.91, RMSEA = .07, CFI = .90, GFI = .96).

Figure 2. The empirical model for the group of migrants. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

A significant positive relationship was found between perceived security and multicultural ideology (β = .27, p < .01). As we can see, the multiculturalism hypothesis was partially supported: perceived security was positively associated with multicultural ideology; however, security was not associated with the ethnic tolerance of migrants. The contact hypothesis was also partially supported: contacts were positively associated only with the integration strategy. The relationship between contacts and ethnic tolerance was positive but did not reach the level of significance (β = .13, p = .08). The integration hypothesis was partially supported also. The relationship between integration and self-esteem was positive (β = .19, p < .05), while the relationships between the integration strategy and life satisfaction and sociocultural adaptation were not significant. Additional findings for the migrant group were the positive relationships between the assimilation strategy and both life satisfaction (β = .31, p < .001) and sociocultural adaptation (β = .20, p < .01). We also found positive correlations between multicultural ideology and the self-esteem of migrants (r = .19) and between ethnic tolerance and self-esteem (r = .19).

Standardized regression coefficients for the empirical model for the group of Russians are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Standardized regression coefficients for the empirical model for the group of Russians *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

|

|

Dependent variables |

|||||

|

Predictors |

Multicultural ideology |

Ethnic tolerance |

Assimilation |

Integration |

Self-esteem |

Life satisfaction |

|

Perceived security |

.29*** |

-.12 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Contacts |

- |

.13 |

-.14* |

.18* |

- |

- |

|

Assimilation |

- |

- |

- |

- |

-.11 |

.06 |

|

Integration |

- |

- |

- |

- |

.19* |

.19* |

|

R2 |

.09 |

.03 |

.02 |

.03 |

.05 |

.04 |

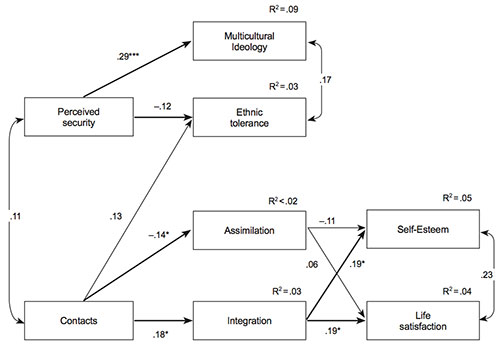

The empirical model for the group of Russians is presented in Figure 3. Goodness-of-fit indicators of the model for Russians were satisfactory (χ2 = 13.89, df = 10, χ2/df = 1.39, RMSEA = .05, CF I= .97, GFI = .98).

Figure 3. The empirical model for the group of Russians. *p < .05, ***p < .001.

A significant and positive relationship was found between perceived security and multicultural ideology (β = .29, p < .001); this result coincides with the result for migrants. The sense of security of Russians was positively associated with multicultural ideology but was not associated with their ethnic tolerance. Therefore, the multiculturalism hypothesis was partially supported. The contact hypothesis was also partially supported. Contacts were negatively associated with the expectation of assimilation (β = –.14, p < .05) and were positively associated with the expectation of integration (β = .18, p < .05). The integration hypothesis was fully supported: we found positive and significant relationships between integration and self-esteem (β = .19, p < .05) and between integration and life satisfaction (β = .19, p < .05).

Discussion

In our study, the integration strategy and the integration expectation were the preferred ways to engage each other among both the migrants from Central Asia and the Russians. This result coincides with the results of previous studies on acculturation in different countries as well as in Russia (Berry & Sabatier, 2010; Jasinskaja-Lahti et al., 2011; Lebedeva & Tatarko, 2009).

We found significant and positive relationships between perceived security and multicultural ideology in the migrants and the majority group but did not find significant relationships between perceived security and ethnic tolerance in either group.

The number and frequency of intercultural contacts were positively (but not significantly) linked to ethnic tolerance in the migrants. Intercultural contacts in the group of Russians were negatively linked to the acculturation expectation of assimilation and positively related to the expectation of integration. We found a significant positive relationship between intercultural contacts and the integration of the migrants as well.

The assimilation strategy of the migrants was positively and significantly related to their sociocultural adaptation and life satisfaction. These results are consistent with the results of some previous studies (e.g., Jasinskaja-Lahti et al., 2011; Ward & Rana-Deuba, 1999). The main aim of migrants from Central Asia in moving to Russia is to improve conditions of life for their families. At the beginning of the acculturation and adaptation process, the strategy of assimilation might seem the best way to reduce perceived cultural and social differences with the host population in order to preempt negative attitudes from the host population. Nevertheless, as predicted, the integration strategy of the migrants was positively related to their self-esteem.

By definition, the integration and assimilation acculturation strategies differ in their level of cultural maintenance. A rejection of one’s own culture by the migrants lowered their psychological well-being, mainly their self-esteem. Among the Russians the integration expectation promoted their better life satisfaction and self-esteem. We can conclude that the Russians did not expect that migrants would reject their own culture, while the migrants considered adopting Russian culture to be important.

Conclusion

Our evaluation of the three hypotheses of intercultural relations in groups of migrants from Central Asia and members of the host population in Central Russia had the following results:

1 The multiculturalism hypothesis was partially supported with both the migrants from Central Asia and the Russians: perceived security promoted an acceptance of multicultural ideology but did not promote ethnic tolerance.

2 The contact hypothesis was partially supported in both samples: intercultural contacts promoted preferences for the integration strategy and expectation but were not associated with the assimilation strategy and expectation.

3 The integration hypothesis was fully supported in the sample of Russians: the integration expectation promoted self-esteem and life satisfaction. This hypothesis was partially supported in the migrant sample: the integration strategy of the migrants had a positive impact on their self-esteem but did not promote their life satisfaction or their sociocultural adaptation.

4 There were some similarities and differences in the relationship between acculturation strategies (of the migrants) and expectations (of the Russians) and their adaptation. For the migrants, assimilation was the best acculturation strategy for achieving better sociocultural adaptation and higher life satisfaction, while integration was the best strategy for achieving high self-esteem. For the Russians, the best acculturation expectation for achieving high self-esteem and life satisfaction was integration. The similarity in the relationship between integration and self-esteem in both samples supports the integration hypothesis and corresponds to most previous findings. However, the finding that the assimilation strategy among the migrants led not only to better sociocultural adaptation (which has been found previously) but also to higher life satisfaction was not predicted. We suppose that such differential findings might be overcome with time. The relationship of the integration strategy to the self-esteem of the migrants is a promising sign that cultural maintenance for migrants will be as useful and functional as cultural participation in the larger host society over time.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is that migrants from Uzbekistan and Tajikistan were considered as a uniform group of labor migrants from Central Asia, although differences could exist in the acculturation of these groups. The second limitation concerns the generalizability of the findings from the Central Federal District of Russia (Moscow) to Russia as a whole. The sample size was not large because of difficulties in accessing migrants, many of whom are often in the country illegally. This limitation could affect the reliabilities of the scales.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 15-1800029).

References

Abashin, S. (2013). Central Asian migration. Practices, local communities, transnationalism. Russian Politics and Law, 51(3), 6–20. doi: 10.2753/RUP1061-1940510301

Arbuckle, J. L. (2011). Amos (Version 20.0) [Computer Program]. Chicago: SPSS.

Berry J. W. (1990). Psychology of acculturation. In J. Berman (Ed.), Cross-cultural perspectives: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (Vol. 37, pp. 201–234). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Berry, J. W. (2013). Intercultural relations in plural societies: Research derived from multiculturalism policy. Acta de Investigación Psicológica, 3(2), 1122–1135. doi: 10.1016/S2007-4719(13)70956-6

Berry, J. W., & Sabatier, C. (2010). Acculturation, discrimination, and adaptation among second generation immigrant youth in Montreal and Paris. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(3), 191–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.11.007

Berry J. W., & Sabatier, C. (2011). Variations in the assessment of acculturation attitudes: Their relationships with psychological wellbeing. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 658–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.02.002

Di Bartolomeo, A., Makaryan, Sh., & Weinar, A. (Eds.). (2014). Regional migration report: Russia and Central Asia. Florence, Italy: Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Geschke, D., Mummendey, A., Kessler, T., & Funke, F. (2010). Majority members’ acculturation goals as predictors and effects of attitudes and behaviours towards migrants. British Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 489–506. doi: 10.1348/014466609X470544

Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Horenczyk, G., & Kinunen, T. (2011). Time and context in the relationship between acculturation attitudes and adaptation among Russian-speaking immigrants in Finland and Israel. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(9), 1423–1440. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2011.623617

Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Liebkind K., Horenczyk, G., & Schmitz, P. (2003). The interactive nature of acculturation: Perceived discrimination, acculturation attitudes and stress among young ethnic repatriates in Finland, Israel and Germany. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(1), 79–97. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(02)00061-5

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Kus-Harbord, L., & Ward, C. (2015). Ethnic Russians in post-Soviet Estonia: Perceived devaluation, acculturation, well-being, and ethnic attitudes. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 4(1), 66–81. doi: 10.1037/ipp0000025

Lebedeva, N. M., & Tatarko, A. N. (Eds.) (2009). Strategii mezhkul’turnogo vzaimodejstvija migrantov i naselenija Rossii: Sbornik nauchnykh statey [Strategies for the intercultural interaction of migrants and the sedentary population in Russia: A collection of scientific articles]. Moscow: RUDN.

Lebedeva, N. M., Tatarko, A. N., & Berry, J. W. (2015). Multiculturalism and migration in post-Soviet Russia. In E. G. Yasin (Ed.), XV aprel’skaja mezhdunarodnaja nauchnaja konferencija po problemam razvitija jekonomiki i obshhestva [XV April International Academic Conference on Economic and Social Development] (Vol. 4, pp. 525–531). Moscow: NIU VShJe.

Masgoret, A.-M., & Ward, C. (2006). Culture learning approach to acculturation. In D. L. Sam &

J. W. Berry (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (pp. 58–77). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511489891.008

Nguyen, A.-M T.D., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2013). Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(1), 122–159. doi: 10.1177/0022022111435097

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ryazantsev, S., & Korneev, O. (2014). Russia and Kazakhstan in Eurasian migration system: Development trends, socio-economic consequences of migration and approaches to regulation. In A. Di Bartolomeo, Sh. Makaryan, & A. Weinar (Eds.), Regional migration report: Russia and Central Asia (pp. 5–54). Florence, Italy: Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute.

Ward, C. (2008). Thinking outside the Berry boxes: New perspectives on identity, acculturation and intercultural relations. Convergence of Cross-Cultural and Intercultural Research, 32(2), 105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.11.002

Ward, C., & Rana-Deuba, A. (1999). Acculturation and adaptation revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30(4), 422–442. doi: 10.1177/0022022199030004003

Wilson, J. (2013). Exploring the past, present and future of cultural competency research: The revision and expansion of the sociocultural adaptation construct (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand.

Zayonchkovskaya, Zh. A., Poletaev, D., Doronina, K. A., Mkrtchyan, N. V., & Florinskaya, Ju. F. (2014). Zashhita prav moskvichej v uslovijah massovoj migracii [Protection of the rights of Muscovites in conditions of mass migration]. In Upolnomochennyj po pravam cheloveka v gorode Moskve [Human Rights Commissioner in Moscow]. Moscow: ROO Centr migracionnyh issledovanij.

Zayonchkovskaya, Zh. A., & Tiuriukanova, E. (Eds.). (2010). Migratsiia i demograficheskii krizis v Rossii [Migration and the demographic crisis in Russia]. Moscow: MAKS Press.

To cite this article: Ryabichenko T. A., Lebedeva N. M. (2016). Assimilation or integration: Similarities and differences between acculturation attitudes of migrants from Central Asia and Russians in Central Russia. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 9(1), 98-111.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.