An existential criterion of normal and abnormal personality in the works of Carl Jung and Carl Rogers

Abstract

This article is the third in a series of four articles scheduled for publication in this journal. In the first article (Kapustin, 2015a) I proposed a description of a new so-called existential criterion of normal and abnormal personality that is implicitly present in the works of Erich Fromm. According to this criterion, normal and abnormal personalities are determined, first, by special features of the content of their position regarding existential dichotomies that are natural to human beings and, second, by particular aspects of the formation of this position. Such dichotomies, entitatively existent in all human life, are inherent, two-alternative contradictions. The position of a normal personality in its content orients a person toward a contradictious predetermination of life in the form of existential dichotomies and necessitates a search for compromise in resolving these dichotomies. This position is created on a rational basis with the person’s active participation. The position of an abnormal personality in its content subjectively denies a contradictious predetermination of life in the form of existential dichotomies and orients a person toward a consistent, noncompetitive, and, as a consequence, onesided way of life that doesn’t include self-determination. This position is imposed by other people on an irrational basis. Abnormality of personality interpreted like that is one of the most important factors influencing the development of various kinds of psychological problems and mental disorders — primarily, neurosis. In the second article (Kapustin, 2015b) I showed that this criterion is also implicitly present in the personality theories of Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, although in more specific cases. In the current work I prove that this criterion is also present in the personality theories of Carl Jung and Carl Rogers, where it is implicitly stated in a more specific way. In the final article I will show that this criterion is also implicitly present in the personality theory of Viktor Frankl.

Received: 18.12.2014

Accepted: 12.11.2015

Themes: Personality psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2016_2/psychology_2016_2_5.pdf

Pages: 54-68

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2016.0205

Keywords: human nature, human essence, existential dichotomy, normal personality, abnormal personality

Introduction

In the first article in this series (Kapustin, 2015a), I described a so-called existential criterion of normal and abnormal personality implicitly present in the works of Erich Fromm (1942, 1947, 1977, 1947/2012) based on an analysis of his works. Fromm developed his theoretical understanding of personality based on the philosophical branch of so-called objective humanistic ethics, which proposes a certain view of how a human being should live. The ultimate moral imperative of a human being who is following what should be considered a standard of life involves the self-determination of values that facilitate living in accordance with human nature.

Based on this school of thought, Fromm proposed his own theoretical concept of human nature. This concept has two characteristics that Fromm considered essential. The first characteristic is that in human life there are existential dichotomies, which are inherent, two-alternative contradictions. They appear to a person as problems requiring solution. The second characteristic is that a human being has self-determination.

The most important concepts in the works of Fromm are concepts of the productive and the nonproductive personality, which are characterized by particular features of content and the formation of the position of a personality in relation to these two characteristics. Fromm defined this position as a scheme of orientation and worship. If the position of a personality in its content and in its way of formation facilitates implementation of these two characteristics, such a personality was defined by Fromm as productive; if not, he defined it as nonproductive. From the point of view of objective humanistic ethics the way of life of a productive personality is a norm of human life because it corresponds to human nature. Thus a productive personality can be considered a normal personality; a nonproductive personality deviates from this norm and is abnormal.

Because Fromm considers the essence of human life to be characterized by existential dichotomies and self-determination, the position of a productive (normal) personality is compromising in its content, matching the contradictive structure of human life in the form of existential dichotomies, and it is created by oneself, based on life experience and reason — that is, on a rational basis.

On the contrary, the position of a nonproductive (abnormal) personality denies the contradictive structure of human life in the form of existential dichotomies orienting the person toward a consistent, noncompetitive, and, as a consequence, one-sided way of life. A specific feature of this position is that it is imposed by others and is based on wishes and feelings toward them — that is, on an irrational basis. From the point of view of Fromm, abnormality of personality interpreted like that is one of the most important factors influencing the development of various kinds of psychological problems and other mental disorders — primarily, neurosis.

Given that in the works of Fromm the criterion for differentiating normal and abnormal personalities is specific features of their position toward existential dichotomies, I mark this criterion as existential. According to this criterion, normality and abnormality are determined first by special features of content and second by particular aspects of the formation of a position toward existential dichotomies, which are entitatively existent in human life and are inherent, two-alternative contradictions that appear to a human being as problems requiring solution.

The essential attribute of a normal personality is a person’s orientation toward the contradictious predetermination of life in the form of existential dichotomies and the need to search for compromise in their resolution. A distinct feature of the formation of this position is that it develops on a rational basis with the active participation of the person — that is, on the basis of knowledge, the source of which is the person’s own experience and reason. The position of an abnormal personality subjectively denies the contradictious predetermination of life in the form of existential dichotomies and orients a person toward a consistent, noncompetitive, and, as a consequence, one-sided way of life that doesn’t include self-determination. Such a position is imposed by other people on an irrational basis: on the basis of wishes for and feelings toward them.

In the second article in this series (Kapustin, 2015b) I showed that this criterion is also implicitly present in the personality theory of Sigmund Freud towards more special existential dichotomy of nature and culture, and in the personality theory of Alfred Adler towards more special existential dichotomy of superiority and community.

Objectives

The main objective of this article is to show that the new existential criterion of normal and abnormal personality based on the works of Fromm is implicitly present in the theories of personality of Carl Jung and Carl Rogers, although in a rather special way. In the final article in this series, I will show that this criterion is also implicitly present in the personality theory of Viktor Frankl.

The existential criterion in carl Jung’s theory of personality

Theoretical discussion

Carl Jung’s view of personality was based on his more general idea about the structure and development of the human mind, which he regarded in turn within the context of biological evolution and anthropogenesis. In his opinion, a mind as a modern human has it, which Jung called consciousness or a conscious mind, has not always been intrinsic but was gradually formed in the long process of evolution, which lasted millions of years.

Describing the process of the evolution of a human mind, Jung formulated an important theoretical law, similar to the one existing in the theory of biological evolution: during the process of phylogeny there emerge in the human mind not only qualitatively new ways of representing the world, typical for the different stages of development, but also their conservation, in rudimentary forms at least. Hence, from the point of view of Jung, the human mind is a multilayered formation, in which the conscious mind is only one, superficial layer. Under it are more archaic layers, corresponding to the qualitatively different developmental stages of the human mind. These layers gradually descend to the developmental stages of the minds of animals, evolutionary ancestors of human beings.

Jung defined all these archaic layers of the human mind, positioned under the upper conscious layer, as the collective unconscious. The content of the collective unconscious consists of the so-called archetypes, preserved traces of archaic ways of representing the world, which pertain to the predecessors of modern, civilized human beings.

In addition to consciousness and the collective unconscious, these two massive layers of a human mind that appeared in the process of evolution, Jung pointed out a third layer, which is structurally positioned between them. He called this third layer the personal unconscious. It represents a structural field of mind, which also contains unconscious content, but, distinct from archetypes of the collective unconscious, it emerges during the process of an individual human life.

The most important statement of Jung’s theoretical model describes the relationships between the conscious and the unconscious, which includes at the same time the personal and the collective unconscious. As Jung pointed out, the unconscious performs a compensatory function in relation to consciousness. This statement is, in turn, closely related to Jung’s more general philosophical ideas about the nature of human life, so it is worth looking at them in a detailed manner.

Characterizing the nature of human life, Jung pointed out that it is objectively set as a unity of opposites:

Man’s real life consists of a complex of inexorable opposites — day and night, birth and death, happiness and misery, good and evil. We are not even sure that one will prevail against the other, that good will overcome evil, or joy defeat pain. Life is a battleground. It always has been, and always will be; and if it were not so, existence would come to an end.(1964/1969, p. 85)

In another place, characterizing this principle of human life, he wrote:

everything human is relative, because everything rests on an inner polarity; for everything is a phenomenon of energy. Energy necessarily depends on a pre-existing polarity, without which there could be no energy. There must always be high and low, hot and cold, etc., so that the equilibrating process — which is energy — can take place. (1917, 1928/1972, p. 75)

According to Jung, most people do not take into account this characteristic of human life. Instead of living in accordance with their nature — that is, considering the necessity of having both polarities simultaneously present in their lives — they take a one-sided position, or, in his terms, a one-sided conscious attitude. Such people acknowledge only one life aspect as meaningful and important, and, at the same time, they devaluate and deny the importance and meaning of the opposite. As Jung wrote:

The very word ‘attitude’ betrays the necessary bias that every marked tendency entails. Direction implies exclusion (1923/1971, p. 83).

The compensatory function of the unconscious consists in its ability to perceive the one-sidedness (bias) of the conscious attitudes of a person and to react to them in a particular way. One such reaction of the unconscious is creating the images of a dream, which should be regarded as a symbolic language; dreams allow the unconscious to point out to a person the one-sidedness of conscious attitudes and the necessity of compensating for it in order to establish accord between these attitudes and the principle of human life: the principle of the unity of opposites.

The existential criterion of normal and abnormal personality is implicitly set in Jung’s works, in his theoretical conceptualization of personality, which is, respectively, nonpredisposed and predisposed to developing psychological problems of different kinds and mental disorders. From my point of view, in the theory of Jung normality and abnormality of personality (respectively, nonpredisposition and predisposition to developing psychological problems and mental diseases) can be characterized using its three main specific features: the level of integration between the conscious and the unconscious mind; specific features of conscious attitudes, which determine how each person resolves the problem of opposites, entitatively existent in life; and the degree of freedom each person has to master behavior and organize life as a whole.

An abnormal personality (predisposed to psychological problems and mental disorders) is characterized by a high level of disintegration of the conscious and the unconscious mind. People with abnormal personalities rely on their conscious mind only, without understanding that they also have an unconscious mind and that they need to consider its reactions when making vital decisions.

Another distinct feature of an abnormal personality is a relatively high degree of one-sidedness in conscious attitudes.

The third characteristic of abnormal personality is closely related to the other two. A result of the one-sidedness of conscious attitudes is activation of the unconscious, which tries to compensate for this one-sidedness. But because people with abnormal personalities do not know anything about their unconscious and do not understand its reactions, it is no wonder that there is no real-life conscious compensation. At this point the activated unconscious begins to interfere with the functioning of the conscious mind and to influence human behavior.

According to Jung, strongly pronounced and resistant conscious attitudes of an abnormal personality may lead to various mental and behavioral disorders. This is how Jung himself described the mechanism of the development of such disorders:

We find it eminently characteristic of abnormal people that they refuse to recognize the compensating influence which comes from the unconscious and even continue to emphasize their one-sidedness. … The mentally unbalanced person tries to defend himself against his own unconscious, that is to say, he fights against his own compensating influences. … This results in a condition of excitation, which produces a great lack of harmony between the conscious and unconscious tendencies. The pairs of opposites are torn asunder, the resultant division leads to disaster, for the unconscious soon begins to obtrude itself violently upon the conscious processes. Then come odd and incomprehensible thoughts and moods, and often incipient forms of hallucination, which plainly bear the stamp of the internal conflict. (1914, p. 966)

As contrasted with an abnormal personality, a normal personality (nonpredisposed to developing psychological problems and mental disorders) has three characteristic aspects. The first is a high level of integration of the conscious and the unconscious mind. Such integration results in the equal participation of both structures in the organization of human life. Jung called this phenomenon Self. According to his definition:

The Self designates the whole range of psychic phenomena in [humans]. It expresses the unity of the personality as a whole. … Empirically, therefore, the Self appears as a play of light and shadow, although conceived as a totality and unity in which the opposites are united (Jung & Baynes, 1921/1976, p. 460).

From Jung’s point of view, acquiring the Self should be regarded as a universal human ideal that everyone should try to reach because this ideal conforms to human nature, and rejection of it leads to discord within oneself. Acquiring the Self is possible only with a radical change of the position one takes toward one’s unconscious; this change results in admitting that the unconscious exists and that it is an appropriate source of wisdom and experience, which one should rely on. As a result of this changed attitude toward the unconscious, one begins to investigate it, learns to understand its reactions and to appropriately compensate for one-sided conscious attitudes. Such a changed attitude toward one’s unconscious, which becomes an ally whose advice should be taken into account, was vividly described by Jung as a shift in the center of personality:

If we picture the conscious mind, with the ego as its centre, as being opposed to the unconscious, and if we now add to our mental picture the process of assimilating the unconscious, we can think of this assimilation as a kind of approximation of conscious and unconscious, where the centre of the total personality no longer coincides with the ego, but with a point midway between the conscious and the unconscious. This would be the point of new equilibrium, a new centering of the total personality, a virtual centre which, on account of its focal position between conscious and unconscious, ensures for the personality a new and more solid foundation. (1917, 1928/1972, p. 221)

The second characteristic aspect of a normal personality is related to the specificity of its conscious attitudes. Because of the general orientation of a normal personality toward interaction with the unconscious, conscious attitudes already cannot be one-sided, as happens with an abnormal personality. Conscious attitudes of a normal personality combine both opposites, which are present simultaneously, without excluding each other; this combination of opposites is to a great extent congruent with the nature of human life, which is set as a unity of opposites. Such a mentality is unusual for a modern, civilized human. As a result, according to Jung, unfortunately our Western mind, lacking all culture in this respect, has never yet devised a concept, nor even a name, for the union of opposites through the middle path, that most fundamental item of inward experience, which could respectably be set against the Chinese concept of Tao” (1917, 1928/1972, p. 205).

Finally, the third aspect of a normal personality is that it is an individuated personality. Exploring the concept of individuation, Jung mentioned that it means, above all, a process of self-healing or self-realization, whose distinct feature is that one lives for oneself, manages life freely and independently, and takes responsibility for it.

In Jung’s opinion, the main block in the individuation process is rooted in oneself, in one’s unconscious. A person with a discorded mind and one-sided conscious attitudes — that is, an abnormal personality — inevitably falls under the power of the irrational forces of the unconscious. As a result, the person has thoughts, images, feelings, and actions imposed by the unconscious, and this imposition by the unconscious makes the individuation process impossible. Jung points out:

[Such an influence from the side of the unconscious creates] a compulsion to be and to act in a way contrary to one’s own nature. Accordingly a man can neither be at one with himself nor accept responsibility [for] himself. He feels himself to be in a degrading, unfree, unethical condition. … deliverance from this condition will come only when he can be and act as he feels is conformable with his true self. … When a man can say of his states and actions, ‘As I am, so I act,’ he can be at one with himself, even though it be difficult, and he can accept responsibility for himself even though he struggle against it. We must recognize that nothing is more difficult to bear than oneself. … Yet even this most difficult of achievements becomes possible if we can distinguish ourselves from the unconscious contents. (1917, 1928/1972, p. 225)

The intention of a normal personality to communicate and cooperate with its own unconscious results in mastering its influence, which Jung regarded as a necessary condition for undertaking the individuation process.

Results

Based on the comparison of the theories of personality by Jung and Fromm, one may conclude that they have two similar statements.

First, the theory of Jung is based on a fundamental philosophical presumption that characterizes the nature of human life: that life is predetermined as a unity of opposites. As a result, a person constantly faces various contradictive requirements, raised from the opposite sides of reality, that must be fulfilled at the same time. The most common example of a contradiction of this kind is the contradiction between the conscious attitudes of a person and compensating claims from the unconscious, which are the total opposite of these attitudes. Taking such characteristics into account, we may regard these contradictions as existential dichotomies in Fromm’s terms and classify them as dichotomies of opposites. Because contradictions may appear not only between the opposites but also between any incompatible sides of reality, one may conclude that dichotomies of the opposites form a narrower class of existential dichotomies.

Second, the existential criterion of distinguishing normal and abnormal personality is implicitly present in Jung’s theoretical conceptualization of personality, which is, respectively, nonpredisposed and predisposed to developing psychological problems and mental disorders, and is characterized by the same particular features of the content and formation of this position as in Fromm’s theory, although in relation to this narrower class of existential dichotomies. Such a position is described in Jung’s works as a conscious attitude.

The position of a normal personality in its content (nonpredisposed to developing psychological problems and mental diseases) orients a person toward a contradictious predetermination of life in the form of the existential dichotomy of the opposites. A person with such a position admits the presence of dichotomies of that kind and regards them as the necessary simultaneous realization of opposite requirements, which they contain: above all, those of the conscious and the unconscious mind. Thus, the position of a normal personality is a position of reasonable compromise, which makes it possible to follow, in Jung’s words, the middle path, by combining both opposites and, at the end, acquiring the Self. The position of a normal personality is achieved on a rational basis with the active participation of a person in the process of self-cognition — above all, in the cognition of the personal and the collective unconscious.

The position of an abnormal personality (predisposed to developing psychological problems and mental diseases) in its content is one-sided in the sense that one considers it meaningful and important to realize only some aspects of life, those that match one’s conscious attitudes, in disregard of the opposites, which one is not conscious of. Unlike Fromm, Jung did not explain directly how the attitude of an abnormal personality is formed, but he, like Fromm, came to the conclusion that an abnormal personality, taking a one-sided position toward objective life conditions, inevitably falls under the sway of the irrational forces of the unconscious, which control human behavior despite one’s will and reason.

Conclusion

The existential criterion of normal and abnormal personality based on the works of Fromm is also implicitly present in Jung’s theory personality, respectively, nonpredisposed and predisposed to developing various psychological problems and other mental disorders, toward more special existential dichotomies of opposites.

The existential criterion in carl Rogers’s theory of personality

Theoretical discussion

The concept of self-actualization has a key position in Carl Rogers’s theory of personality. The term self-actualization is a composite of two words. According to Rogers, the word actualization means a tendency toward growth and development according to innate potential capacities inherent in all of living nature. As an example, we may point to the seed of any plant, which initially has a potential for growth and development and, being placed in appropriate conditions, begins to grow and develop, achieving its potential. The word self points to the particular object of actualization: a human personality. Thus self-actualization is the actualization of the innate human tendency to grow and develop according to one’s natural potential. As in the case of the seed, the tendency to grow and develop is inherent in human nature as a potential ability, which, in a particular environment, may begin its actual realization.

In Rogers’s opinion, psychotherapeutic communication between therapists and clients, typical in client-centered therapy, is one of such kinds an environment characterized by three main specific features. The first is the openness and honesty of therapists in expressing the thoughts and feelings that occur to them in the process of conversation with the clients; in other words, when therapists say something to their clients, they always express only what they really think and what they really feel. The second specific feature includes both therapists’ unconditional positive acceptance of patients as people who have unconditional value and therapists’ nonjudgmental attitude toward their clients. The third specific feature is therapists’ empathic perception of the inner world of their clients, which involves therapists’ ability to feel and understand the subjective experience of their clients just as the clients themselves feel and understand it (therapist congruence).

According to Rogers, clients placed in such an environment start to perceive themselves more positively and in a nonjudgmental way. Rogers regarded such a change of attitude toward oneself as a kind of trigger that initiates the process of self-actualization, transferring it from a potential to an actual state. As a result, a client’s personality starts to self-actualize — that is, to grow and develop naturally — in the process of fulfilling its potential, which is inherent in its nature.

Developing a detailed conceptualization of a self-actualizing personality, Rogers pointed to a number of inherent specific features. Here I will discuss only four of them, which can be considered the main features because they are present in all the descriptions of a self-actualizing personality that Rogers gave in different works.

The first feature is openness to experience. This feature is fundamental because it is a prerequisite for the existence of other three. Openness to experience is one’s special orientation toward the unprejudiced perception of the objective content of one’s conscious experience — above all, of the experience related to representations about the self. It is a natural consequence of unconditional positive regard and unconditional self-attitude, which lead to the elimination of subjectivity and bias in regard to oneself. The result of openness to experience is that representations about the self, which Rogers called the self or self-concept, become more and more empirically grounded and, as a consequence, increasingly correspond to what a person is in reality.

The second feature is called trust in one’s organism, which occurs when one regards one’s organism as a reliable source of objective, conscious experience. When solving various kinds of problems, people who have this feature are inclined to listen to themselves, to their own experiences, to have what Rogers called “total organismic sensitivity” (1961/1995, p. 202).

The third feature is internal locus. It indicates that a self-actualizing personality is characterized by self-determination of the objectives of life and of the ways of achieving them. This feature is closely related to the previous one because if people experience trust in their organisms as a reliable source of objective experience, it is natural that they exhibit a disposition to rely on themselves and not on any external influences.

The fourth feature is a wish to exist as a process. A person with this feature wants to stay in a never-ending process of growth and development, which is a self-actualization process. People with self-actualizing personalities are open to experience, trust their organisms and rely on their own experiences when solving problems; these experiences are constantly changing in the process of incessant growth and development, and thus it is common for such people to be in a state of change and incompleteness rather than in a state of permanence and definiteness.

The concepts of self-actualization and self-actualizing personality in Rogers’s theory are closely related to the definition of normal and abnormal personality. The existential criterion for distinguishing these two types is implicitly present in the works of Rogers, as well as in the works of Jung, in his theoretical ideas about personality, which is, respectively, nonpredisposed and predisposed to developing psychological problems of different kinds and to mental disorders.

An abnormal (predisposed to developing life problems of different kinds and to mental disorders) personality in general can be defined as non-self-actualizing — that is, as a personality whose process of self-actualization is blocked and exists only potentially. The main hindrance to the self-actualization process is rooted in humans themselves; this hindrance is a system of so-called conditional values, which are conditions of humans regard toward the other people and toward the self (Rogers, 1959). If personal qualities of the others or the self accord these values they deserve of the positive regard, otherwise the regard toward them is negative.

Conditional values begin to form in early infancy on the basis of two needs that are closely related to each other: an inborn need for positive regard from others, especially from significant others, and a derivative need for positive self-regard. Using these needs, adults, parents in particular, may impose conditional values that they consider necessary.

Conditional values were regarded by Rogers not only as the main hindrance to the self-actualization process but also as a fundamental factor in the development of abnormal personality. Rogers refrained from calling an abnormal personality, developed under the influence of conditional values, a personality, saying that the term mask is more apt. Comparing such a personality to a mask emphasizes that it is just a cover, made by someone else, that hides a real personality, to the development of which one is predisposed by one’s own nature.

Rogers’s view of a mask-like abnormal personality is the opposite of his idea of a self-actualizing person. This interpretation can be proved by comparison of the main features of an abnormal personality and the four features of a self-actualizing personality described above.

The first above-mentioned feature of a self-actualizing personality, openness to experience, is a predisposition toward the unprejudiced perception of the objective content of one’s conscious experience, including, above all, one’s self-concept. An abnormal personality, on the contrary, is characterized by a subjective bias toward the perception of one’s own experience. Such a bias manifests itself in the human ability to perceive only that part of one’s experience that meets one’s positive value self-representations, which are under the influence of conditional values. The other part of one’s experience is not perceived at all or is perceived with such distortions that the experience doesn’t contradict one’s positive value self-representations. The main reasons for the nonperception and distortion of experience are a human need for positive regard from other people and a need for self-regard, which sets one to match the ideal of the conditional values imposed by others.

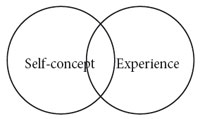

In general we may illustrate this feature on a model of personality structure by Rogers, shown on Figure 1. One of the intersected circles, self-concept, symbolizes subjective self-representations. Another circle, experience, symbolizes all of one’s

objective conscious experience of oneself. The intersection indicates that a part of one’s experience is perceived consciously, without any distortions, and corresponds to one’s self-representations. At the same time one also has experience, which contradicts these self-representations and is perceived perversely or isn’t perceived at all. Such experience symbolically remains outside the intersection.

Figure 1. Model of the structure of personality (Rogers, 1959, 1965)

This model helps to illustrate the discussed difference between self-actualizing and abnormal personality, based on the feature openness/bias toward experience, which determines the degree of reality/distortion of self-representations. In the model this reality/distortion degree corresponds to the area of intersection and was called by Rogers the “degree of congruence of self-concept and experience.” Full congruence means complete intersection or overlapping of these circles. Such congruence is typical of a fully self-actualizing and opened-to-experience personality, which has absolutely realistic and unbiased self-representations, including contradictious ones.

[A human opened to experience] is the one who is as aware of the demands of the culture as it is of its own physiological demands for food or sex — which is just as aware of its desire for friendly relationships as it is of its desire to aggrandize itself — which is just as aware of its delicate and sensitive tenderness towards others as it is of its hostilities toward others. (1961/1995, p. 105)

In another place, also describing the same type of experience of a person in the process of self-actualization, Rogers noted:

He feels loving and tender and considerate and cooperative, as well as hostile, or lustful, or angry. He feels interest and zest and curiosity, as well as laziness or apathy. He feels courageous and venturesome, as well as fearful. His feelings, when he lives closely and acceptingly with their complexity, operate in a constructive harmony rather than sweeping him into some uncontrollably evil path. (1961/1995, p. 177)

On the contrary, complete incongruence indicates the presence of illusionary, fully distorted self-representations, which do not correspond to reality. It is obvious that such cases should be regarded only as theoretical samples, as they scarcely exist in reality.

The second feature of abnormal personality is also the opposite of the previously discussed second feature of a self-actualizing personality. If a self-actualizing personality is characterized by trust in its organism as a source of objective experience, an abnormal personality rather trusts its subjective self-representations, which are based on conditional values. As a consequence, an abnormal personality faces a mismatch between the contents of the self and experience, and these two structures confront each other. Rogers described objective experience that doesn’t match conditional values as an objective danger because it can destroy self-representations and the integrity of the self. Such an objective experience is a source of anxiety, from which a human tries to defend by distorting the objective content of experience.

The third feature of a self-actualizing personality, internal locus, is characterized by self-determination in choosing goals and ways of achieving them. On the contrary, the third feature of an abnormal personality, external locus, is to a large extent driven by conditional values, which are imposed by other people in early childhood in order to change behavior in a way they believe is needed. Such intrusion is based on the human need for the positive regard of other people and for positive self-regard. Despite the fact that, later, these conditional values are perceived by the abnormal personality as its own, we, taking their source into account, may say that its behavior stays in irrational dependence on them as external forces.

The fourth feature of an abnormal personality is that it is inclined to be in a state of permanence and determinacy. It is conditioned by the fact that self-representations of an abnormal personality are based on a relatively stable system of conditional values and not on constantly changing experience, and they also have the ability to actively resist changes toward correspondence with experience by the means of distortion of their objective content.

According to Rogers, a normal personality (not predisposed to developing psychological problems and mental diseases) is typical of a fully functioning person, who is described in his works as a person having the features of a self-actualizing personality, but this description is almost always given not in the absolute, but in relative characteristics, in comparison with an abnormal personality.

Thus, a normal personality is characterized not by openness to experience, but by more openness to experience; not by trust in its organism, but by more trust in its organism; not by internal locus, but by more internal locus; not by a wish to exist as a process, but by a stronger wish to exist as a process; and so on. As an example of such a description we may use an extract from one of Rogers’s works, in which he gave a condensed characterization of a normal human personality that has successfully undergone a course of client-centered therapy. In this extract the underlined words indicate a comparison between characteristics of normal and abnormal personalities.

[After successfully performed psychotherapy, the] individual becomes more integrated, more effective. He shows fewer of the characteristics which are usually termed neurotic or psychotic, and more of the characteristics of the healthy, well-functioning person. He changes his perception of himself, becoming more realistic in his views of self. He becomes more like the person he wishes to be. He values himself more highly. He is more self-confident and self-directing. He has a better understanding of himself, becomes more open to his experience, denies or represses less of his experience. He becomes more accepting in his attitudes toward others, seeing others as more similar to himself. In his behavior he shows similar changes. He is less frustrated by stress, and recovers from stress more quickly. He becomes more mature in his everyday behavior as this is observed by friends. He is less defensive, more adaptive, more able to meet situations creatively. (1961/1995, p. 36)

From my point of view, such a comparative description is not a coincidence. It is related to the fact that, as was discussed previously, besides an inherent tendency to self-actualization, a human has an inherent need for the positive regard of other people, which is often satisfied only on condition of matching the qualities of his personality to the conditional values shared by significant others.

Results

Based on this comparison between the theories of personality by Carl Rogers and Fromm, we may conclude that they are similar in two ways.

First, in Rogers’s theory this statement has great importance: there is a contradiction between two different directions of personal development in human life; this contradiction makes a human have a need for self-determination related to his development. One of these directions is set by an inherent human tendency to self-actualization; another, by a human striving after conformity of personal qualities to the conditional values imposed by others. Such a contradiction can be regarded as inherent to human nature because the self-actualization tendency is innate, and human striving after conformity of personal qualities to conditional values is a necessary condition of satisfaction another inherent need, the need for positive regard from significant others. The listed characteristics of this contradiction allow us to classify it according to Fromm as an existential dichotomy and to name it a dichotomy of self-actualization and conditional values.

Second, the existential criterion of distinguishing normal and abnormal personality implicitly present in Carl Rogers’ theoretical conceptualization of personality, respectively, non-predisposed and predisposed to developing psychological problems and mental disorders, and is characterized by the same particular features of the content and formation of this position as in Fromm’s theory, although in relation to this more particular existential dichotomy.

The position of a normal personality (nonpredisposed to developing psychological problems and mental diseases) in its content orients one toward a contradictious predetermination of life in the form of an existential dichotomy of self-actualization and conditional values. A person with such a personality is aware of this contradiction and finds a way of resolving it through compromise and thus becomes a fully functioning human without losing the aim of achieving conformity of personal qualities and the conditional values of other people, which is necessary for social adaptation. Such a position is developed with one’s active participation on a rational basis within the process of self-cognition — above all, cognition of one’s own experience, perversely realized and unconscious.

The position of an abnormal personality (predisposed to developing psychological problems and mental diseases) in its content one-sidedly orients a human toward achieving conformity of personal qualities to the conditional values of other people, which inhibits realization of the self-actualization tendency in life. Such a position is imposed in early infancy by other people — above all, by parents — on an irrational basis — on the basis of a need for positive regard from other people and positive self-regard.

Conclusion

The existential criterion of normal and abnormal personality based on the works of Fromm is also implicitly present in Rogers’s theory of personality as being, respectively, nonpredisposed and predisposed to developing various psychological problems and other mental disorders. Rogers’s theory, however, is based on the special case of an existential dichotomy of self-actualization and conditional values.

Application of the results

I have shown in a number of empirical studies (Kapustin, 2014, 2015c, 2015d, 2015e) that the key factor leading to child-parent problems in families of psychological-consultation clients is the abnormality of the parents’ personality, identified through a so-called existential criterion that is displayed in their parenting styles. These parenting styles contribute to the formation of children with abnormal personality types, also identified through existential criteria, that are designated as “oriented on external help,” “oriented on compliance of one’s own behavior with other people’s requirements,” and “oriented on protest against compliance of one’s own behavior with other people’s requirements.” Children with such personality types are faced with requirements from their closest social environment that are appropriate for children with normal personality development but are not appropriate for those with abnormal personal abilities, and so they start having problems. As these problems are connected with troubles of adjustment to social-environment requirements, they can be classified as problems of social adaptation. I have identified a similarity between the personality type “oriented on compliance of one’s own behavior with other people’s requirements” and theoretical concepts in the work of Fromm, Freud, Adler, Jung, Rogers, and Frankl about the predisposition of people with an abnormal personality to having various psychological problems and mental disorders. These similarities suggest that a personality of this type can be regarded as a classic type that all these authors faced in their psychotherapeutic practice at different times. It was shown, that abnormal personality types, formed in childhood, influenced the formation of large amount of personal problems in adulthood (Kapustin, 2016).

References

Fromm, E. (1942). Fear of freedom. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner.

Fromm, E. (1947). Man for himself. An inquiry into the psychology of ethics. New York: Rinehart.

Fromm, E. (1977). To have or to be? New York: Continuum.

Fromm, E. (2012). Chelovek dlya sebya [Man for himself]. Moscow: Astrel. (Original work published 1947)

Jung, C. G. (1914). On the importance of the unconscious in psychopathology. British Medical Journal, 2(2814), 964–968.

Jung, C. G. (1969). Approaching the unconscious. In Man and his symbols. New York: double-day. (Original work published 1964)

Jung, C. G. (1971). On the relation of analytical psychology to poetry. In "The spirit in man, art, and literature" (vol. 15 of The Collected Works of C. G. Jung). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1923)

Jung, C. G. (1972). Two essays on analytical psychology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original works published 1917, 1928)

Jung, C. G., & Baynes, H. G. (1976). Psychological types. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1921)

Kapustin, S. A. (2014). Stili roditel’skogo vospitaniya v sem’yah klientov psihologicheskoj konsul’tacii po detsko-roditel’skimi problemami [Styles of parenting in families of psychological-consultation clients for parent-child problems]. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Seriya 14: Psikhologiya [Moscow University Psychology Bulletin], 4, 76–90.

Kapustin, S. A. (2015a). An existential criterion for normal and abnormal personality in the writings of Erich Fromm. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 8(2), 87–98. Doi: 10.11621/ pir.2015.0208

Kapustin, S. A. (2015b). An existential criterion for normal and abnormal personality in the works of Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 8(3), 4–16. Doi: 10.11621/pir.2015.0301

Kapustin, S. A. (2015c). Ispol’zovanie ehkzistencial’nogo kriteriya dlya ocenki lichnosti giperopekayushchih i sverhtrebovatel’nyh roditelej v sem’yah klientov psihologicheskoj konsul’tacii po detsko-roditel’skim problemam [The use of an existential criterion for assessing the personality of hyperprotecting and overexacting parents in families of psychological-consultation clients for parent-child problems]. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Seriya 14: Psikhologiya [Moscow University Psychology Bulletin], 2, 51–62.

Kapustin, S. A. (2015d). Osobennosti lichnosti detej v sem’yah klientov psihologicheskoj konsul’tacii [Personal features of children in client families who receive psychological advice]. Natsionalniy Psikhologicheskiy Zhurnal [National Psychological Journal], 1(17), 79–87.

Kapustin, S. A. (2015e). Stili roditel’skogo vospitaniya v sem’yah, nikogda ne obrashchavshihsya v psihologicheskuyu konsul’taciyu, i ih vliyanie na razvitie lichnosti detej [Styles of parenting in families who have never applied for psychological counseling and their influence on the personality development of children]. Natsionalniy Psikhologicheskiy Zhurnal [National Psychological Journal], 4(20), (in press).

Kapustin, S. A. (2016). Ispol’zovanie rezul’tatov issledovaniya semey s detsko-roditel’skimi problemami v praktike psikhologicheskogo konsul’tirovaniya vzroslykh lyudey [Using the results of the study of families with parent-child problems in the practice of counseling adults]. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Seriya 14: Psikhologiya [Moscow University Psychology Bulletin], 1, 79–95.

Rogers, C. R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a science (vol. 3, pp. 184–256). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, INC.

Rogers, C. R. (1965). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications, and theory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Rogers, C. R. (1995). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view on psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. (Original work published 1961)To cite this article: Kapustin S. A. (2016). An existential criterion of normal and abnormal personality in the works of Carl Jung and Carl Rogers. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 9(2), 54-68.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.