Ethno-confessional identity and complimentarity in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia)

Abstract

This article is based on the empirical data gained from a previous study “Ethnic-confessional relations in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) in 2011- 2013”. In the mid-nineties in the 20th century, the number of nationalities that were nontypical for the Far East, Siberia and the Far North of Russia began to enlarge, and the trend continues year by year. According to the analysis results, people who migrate are attracted to the republic. The capital of the republic, the industrial cities of Yakutsk, Mirny, and Aldan, as well as the settlements of Niznij Bestyakh of the Megino-Kangalasskij district and Kysyl-Syr of the Viluiskij district, are the center of the migration stream. To define the ethnic and confessional complementariness of the local population, a test-scale by Yu.I Zhegusov was used. The authors of the study refused a simple dichotomous division of ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’, and suggested a more complicated structure. In ethnic-confessional complementariness, the following levels and degrees were used:

- positive complementariness is expressed as ‘insiders’ who may be closely related( friendly terms, blood relationship)

- neutral complementariness is expressed as ‘outsiders’ with whom one may co-exist, but avoids close relations

- negative complementariness is expressed as ‘outsiders’ who are undesirable to live in a neighborhood with

- critical level of complementariness is expressed as ‘enemies’ who constitute a danger and threat.

On the whole, the research shows some peculiarities:

-

Russians are mostly comfortable with representatives of other ethnic groups and religions. In Yakutia, they feel confident in the context of ethnic and migration process intensification.

-

Yakuts show an alarmist public mood and worry about their future, and they are afraid of losing their ethnic status and national identity as a result of the uncontrollable process of migration and assimilation.

Received: 23.10.2015

Accepted: 25.01.2016

Themes: Multiculturalism and intercultural relations: Comparative analysis; Psychology of ethno-cultural issues

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2016_1/psychology_2016_1_5.pdf

Pages: 74-83

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2016.0105

Keywords: ethnicity, complimentarity, nationalism, Russia, Yakutia

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to separate the level of complimentarity between the dominant ethnic and religious groups — Yakuts (etnonim — Sakha, further: Sakha) and Russian — from the general context of the study “Ethno-confessional relations in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) for 2011-2013”.

Complimentarity is one of the key factors of interethnic and interconfessional solidarity in conditions of migration expansion and the transformation of Russian society. The topic of ethno-confessional complimentarity is based on the fact that in the last twenty years, significant social transformations of the ethnic and religious composition in the Russian Federation have occurred: ethnic groups that are atypical of the Russian Far East and North migrated to the Sakha Republic, and urbanization and desecularization continued.

In its dependence on identity, inter-ethnic and inter-confessional complementarity affects interdisciplinary subject areas of science, such as psychology, cultural anthropology and ethnosociology, which studies ethnicity and inter-ethnic relations.

Positive complimentarity is expressed by shared values, a similar worldview, and close cultural and taste preferences, and negative complimentarity appears in opposite value orientations, with a different attitude, and is alien to cultural and taste preferences. Complimentarity reflects a subconscious feeling of mutual sympathy (antipathy) between members of ethnic groups, which determines the division into “us” and “them”. The positive complimentarity at different times passes from the unconscious mutual attraction of consortium to conviction, which is the formation of common habits, attitudes, and tastes united by a common way of life (Gumilev, 2008, p. 210).

Negative complimentarity manifests itself as antipathy, intolerance, and in its most extreme version, genocide. It is well known that positive or negative complimentarity characterizes relations between different ethnic groups and connects with their mentality as an ethnopsychological phenomenon. It provides an opportunity to explain why, regardless of the level of cultural development; in some cases it is possible to establish a friendly ethnic contact, and in others, relations between ethnic groups become undesirable, hostile and even bloody. The problem of positive or negative complimentarity under the modern conditions of globalization as well as the problem of increased migration flows are relevant.

We propose to distinguish between two concepts: ‘complementarity’ and ‘complimentarity’. The etymology of the term ‘complementarity’ comes from the Latin ‘complementarity’, which refers to additionality. The meaning of the term complementarity is more encompassing than ‘complimentarity’ because the first term provides an opportunity to reflect a variety of life aspects: politics, economics, social life, and spirituality. ‘Complementarity’ considers structures that fit together, complement one another and interact in harmony. ‘Complementarity’ is more related to the conscious actions of people because the state of ‘complementarity’ and coherence requires concerted efforts and joint control of interactions. The moral basis of ‘complementarity’ is a partnership based on mutual trust. In turn, ‘complementarity’ becomes a stable pillar of society.

Negative complimentarity manifests itself as antipathy, intolerance, and in its most extreme version, genocide. It is well known that positive or negative complimentarity characterizes relations between different ethnic groups and connects with their mentality as an ethnopsychological phenomenon. It provides an opportunity to explain why, regardless of the level of cultural development; in some cases it is possible to establish a friendly ethnic contact, and in others, relations between ethnic groups become undesirable, hostile and even bloody. The problem of positive or negative complimentarity under the modern conditions of globalization as well as the problem of increased migration flows is relevant.

The term complimentarity (from French compliment) was used by Lev Gumilyov as a principle that is associated with the subconscious mutual sympathy of individuals (Gumilev, 2008, p. 209). Complimentarity reflects a subconscious feeling of mutual sympathy (antipathy) among members of different ethnic groups; it determines the division of ‘us’ and ‘them’. The positive complimentarity over a certain time period passes from the unconscious mutual attraction, consortium, to conviction, which is the formation of common habits, attitude, and taste united by a common way of life (Gumilev, 2008, p. 210).

Thus, this topic is relevant because the changes taking place in contemporary reality occur too quickly and unpredictably, especially for mass perception. Concepts such as “uncertainty”, “risk” (Beck, 2000), “fluidity” (Bauman, 2008), and “precaretization” (Standing, 2014) have become the basis for modern process description language. In the context of “fluid modernity” (Bauman, 2008), the problem of readiness of the mass consciousness for the complementary / complimentary interaction between ethnic and religious groups has become important.

Yakutia is a federal subject in Northeastern Russia. Yakutia has been part of the Russian state since 1632. Since 1991, its official name has been the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). The territory encompasses 3,083,523 square kilometers (geographically the largest region of the Federation), and the population is 956,000 people.

Historically, within the territory of Yakutia in the twentieth century, the national composition was determined as follows: the largest ethnic groups were the Yakut or Sakha, with 466,492 people, and Russian, with 353,649 people. Traditionally, the territory of Yakutia is inhabited by indigenous peoples. Russians, who have a history of family members living in Yakutia for several generations, are more mobile. Russians came to Yakutia as a result of deliberate government policy, such as the peasant colonization in the end of the 17thand early 18th centuries; organization management and the direction of officials; political exile in the 18th century through the beginning of the 20th century; Soviet industrialization and political exile in the 1930s and early 1950s; development of the North from19561991; and so on.

This purposeful policy of the state is typical for the whole history of the Siberian portion of Russia. The concepts of frontier and frontier cooperation (Basalaeva, 2012) are valuable for understanding the nature of the interaction between representatives of Russian and Yakut ethnic groups. In terms of the socio-cultural transformation of Russian society, the topic of “frontier and frontier cooperation” is very popular among researchers from Siberia and the Russian Far East (Ganopolskii, 2005; Shirokov, 2007; Basalaeva, 2012, Mansurov, Mezentsev, & Polikarpov, 2014).

By the end of the Soviet period in the history of Yakutia, a steady, “familiar” ethno-confessional configuration appeared: Yakutians of Russian nationality with a constantly updated stable contingent of the Yakut/Sakha (the Yakut used to be reluctant to migrate to other regions of the USSR), the representatives of Indigenous Peoples of the North (Evens, Evenki, Chukchi, Yukagir, Dolgan) and others (representatives of the peoples of the USSR). As far as the confessionalism of representatives of the major ethnic groups in the Soviet Union is concerned, the country officially followed an atheistic policy, and the religiosity of the population was in a latent state.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and the announcement of the sovereignty of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), the representatives of the non-indigenous population began to leave the republic (in 1989 the population was 1,094,065 in the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (YASSR)).

Since the mid-1990s, the influx of migrants that are non-typical of the indigenous rooted population of the Far East, Siberia and northern ethnic groups and religions has increased. In recent years, citizens of the People´s republic of China (PRC) have migrated to the Yakut. People from the North Caucasus, Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) and the Yakutians (rooted population of Yakutia with a long family history) have been somehow “familiar” since 1960-1991.

The fact that migrants were perceived as atypical in the years from1992 to2014 by indigenous and rooted residents of the republic is connected with the change of the nature of migration and the quality of workers. In the Soviet era, especially between 1960 and1991, Yakutia was visited by specialists who were professionally educated and trained. The Ethnic and religious identity of Soviet specialists was not advertised and had a secondary character.

During the socio-economic reforms of the 1990-2000s, local civil and ethnic conflicts became the impetus for the new migratory flows.

For example, according to the Federal Migration Service of the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic, during the length of the study (10 months in 2013), the migration flows increased by 28(7%).

Within 10 months in 2012, 31,872 entering migrants were recorded, and within 10 months in 2013, 41,029 migrants were reports. In total, 79% of the migrants were foreign nationals who entered for the purpose of employment. The following cities became the centers for migration flow: Yakutsk — 56%, Mirnyi District — 8.9%, Aldan District — 7.7%, and Neryungri region — 6.7%. These data suggest the migration attractiveness of the republic for foreign citizens. In general, it should be noted that migratory streams are determined by specific and varying conditions of time and place.

Empirical study by questionnaires revealed significant differences in ethnic and confessional complimentarity in Russian and Yakut/Sakha.

Method

Goals of research

The purpose of this article is to separate the level of complimentarity between the dominant ethnic and religious groups, Sakha and Russian, from the general context of the study “Ethno-confessional relations in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) for 2011–2013”.

Every society, including the local community of Yakutia, is permeated by invisible, but objectively existing, lines of demarcation, the social boundaries that on the one hand divide the people and social groups and on the other hand are the basis of the formation of other communities.

To determine the ethnic and religious complimentarity of the representatives of the traditional ethnic communities in Yakutia (the Sakha and the Russians), a special test range was developed by the sociologist Yuri Zhegusov. This test renounces the simple dichotomous division into ‘us’ and ‘them’ by offering a more detailed scheme. For example, in ethnic and religious complimentarity the following extent was identified:

- positive complementarity is expressed by ‘them’, individuals with whom you can have a close relationship (friendship, kinship). Complementarity is further intertwined with complimentarity and psychological sympathy;

- there is a neutral complimentarity towards ‘them’, individuals with whom you can live peacefully, but without establishing a close relationship. This demonstrates that psychological alertness to others is complemented by the pragmatics of complementarity;

- negative complimentarily appears to ‘them’, individuals with whom cohabitation is not desirable. In this case, complementarity is not shown;

- critical degree of complimentarity can be traced to ‘enemies’, individuals of which are dangerous and represent a threat. Complimentarity is not possible here.

Sample

For this study, we chose the following survey points: the cities of Yakutsk, Neryungri, Mirny, and Aldan, as well as the urban-type settlements of Nizhniy Bestyakh and Kysyl-Syr. Urban and urban-type settlements were chosen for the study first because 40% of the population of Yakutia lives in these locations and second because of the flow of migrants. Rural settlements are predominantly mono-ethnic and economically unattractive. However, the data indicate the high attractiveness of the republic for migrants.

The study was conducted using the sociological method of questionnaires. During the survey, we used a mixed strategy: at work and at home, in the presence of interviewers and without them. The sample survey was territorial, probabilistic, and stratified. We collected 1,649 questionnaires; 25% of the questionnaires were collected in Yakutsk, 22% in Aldan, 16% in Neryungri, 14% in Mirny, 14% in the village Nizhniy Bestyakh in the Megino-Kangalassky district, and 9% in Kysyl-Syr in the Vilyui district. Concerning the ethnic composition, 51% of the total number of respondents were Russian, 36.6% were Yakuts, and 12.4% were of other ethnic groups.

Results

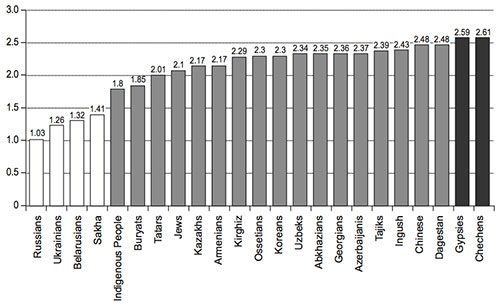

Ethnic and religious complimentarity of the Russians

According to the results of a survey (Figure 1), positive complimentarity was identified among Russian respondents in relation to Slavic people: the Ukrainians and Belarussians. Additionally, Russian respondents consider as ‘us’ the Yakut/Sakha people (indicated in the diagram by white), who have been living together for several centuries.

The Russians show a neutral complementary in relation to the indigenous peoples of the North: the Buryats, Tartars, Jews, Kazakhs, Armenians, Kirghiz, Ossetians, Koreans, Uzbeks, Abkhazians, Georgians, Azerbaijanis, Tajiks, Ingush and Dagestanis and Chinese, i.e., Russians consider the listed nationalities as ‘them’ (marked in grey in the figure).

The survey revealed that Roma and Chechens are ‘strangers’ for Russians (black). The negative experience of social interactions with the Roma in everyday life contributed to the formation of such negative social stereotype of Roma among the Russians. The perception of Chechens by the Russians as ‘strangers’ was formed due to armed conflict with separatists in Chechnya, which involved a large number of military and law enforcement personnel.

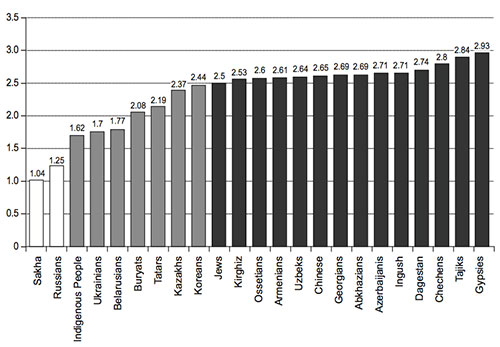

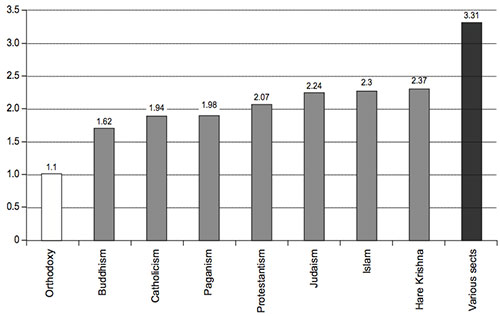

Figure 2. Complimentarity of the Russians in relation to other religions

As for the Russian religious complimentarity (Figure 2), they perceive parishioners of the Orthodox Church as ‘us’. Russians perceive other denominations as neutral, except the group of ‘sectarians’, a designation which initially carries a negative connotation.

Ethnic and religious complimentarity among the Yakut / Sakha

Quite a different picture of complimentarity is seen among Yakut/Sakha respondents (Figure 3). The Sakha perceive only the Russians as positively complimentary, and the Sakha perceive the Russians as ‘friends’, more strongly than the Russians perceive the Sakhaas ‘friends’. The Index of Sakha complimentary to the Russians is 1.25 points, and the Russians to the Sakha is 1.41 points.

According to the results of the study, the neutral complimentarity of the Sakha is observed in relation to the representatives of indigenous peoples, such as Ukrainians, Belarusians, Buryats, Tatars, Kazakhs and Koreans.

The Sakha perceive more than half of the representatives of the ethnic groups noted in the questionnaire with negatively complimentary: the Jews, Kyrgyz, Ossetians, Armenians, Uzbeks, Chinese, Georgians, Abkhazians, Azerbaijanis, Ingush, Dagestanis, Chechens, Tajiks and gypsies.

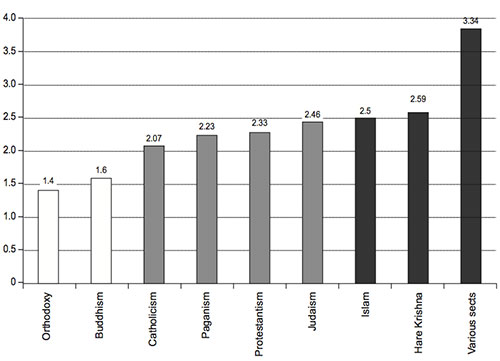

Figure 4. The Yakut/Sakha complimentarity relating to other confessions

The picture of the Yakut confessional complimentarity is quite unexpected (Figure 4). Thus, representatives of the Sakha perceive Orthodoxy closer than paganism and shamanism (which are considered to be their traditional beliefs).

The Yakuts have neutrally complimentarity to Protestants, Catholics, Buddhists and Jews.

The Yakut respondents are mistrustful of Hare Krishnas, Muslims and sectarians.

Conclusion

The method of measuring ethnic and religious complimentariness that has been used in this sociological research has revealed the following features: Russians, in general, have a calm attitude that dominates in relation to the majority of members of other ethnic groups and religions. Russians traditionally have more extensive ties and frequent contacts with representatives of ethnic and religious groups throughout Russia. Therefore, in Yakutia, they feel more confident in the conditions of the ethnic processes’ intensification and the migration of peoples. On the contrary, Yakut / Sakha show alarmist sentiments; they are concerned about their future. They are afraid of losing their ethnic status and identity as a result of uncontrolled migration and assimilation.

In conclusion, the critical degree of complimentariness, which can be traced to “enemies”, appeared to not to exist; neither Russians nor Sakha, given a list of representatives of ethnic groups and religions, named anyone from the list.

There may be several reasons for Yakuts to be alert against “foreigners”:

- Changes in the nature and intensity of the migration processes. For example, there is an exonym in the Yakut language, nuuchcha, to identify Russians who have lived in Yakutia since the eighteenth century. That is, Orthodox Russian are mentally “registered” in the Yakut public consciousness.

There is no special definition for other members of ethnic and religious groups. Their names entered the Sakha language from the Russian language; - The Russians living in Yakutia consider Yakutia as one of many possible territories in which they can live. Many Russians, even those who have roots in Yakutia, now think about the prospect of leaving this place.

For the Sakha, Yakutia is their homeland, the land of their national epos Olonkho, which they call Yakutia Sakha Sire (the Land of the Yakuts). It is not typical for them to have a desire to move to another place, not even in the event of an unfavorable economic situation. By migrating within the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), many Yakut / Sakha retain their ancestral identity and an attachment to their place of birth.

Overall, the following conclusion can be made:

- Russians, on the whole, have a calm attitude that dominates in relation to the majority of members of other ethnic groups and religions. In Yakutia, they feel more confident in the conditions of the ethnic processes’ intensification and the migration of peoples.

- Yakut / Sakha show alarmist sentiments and are concerned about their future. They are afraid of losing their ethnic status and identity as a result of uncontrolled migration and assimilation.

Acknowledgements

This study has been performed within in the framework of the state order contract of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) No. 1175, Ethno-Confessional Relations in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia).

References

Basalaeva, I. (2012). Frontir kak mesto v prostranstvennom analize socialnoj dinamiki [Frontier as a place in the spatial analysis of social dynamics. Vestnik Kemerovskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta kul’tury i iskusstv [Kemerovo State University of Culture and Arts Herald], 18, 208-215.

Basalaeva, I. (2012). Kriterii frontira: K postanovke problem [Criteria frontier: to the problem]. Teorija i praktika obshhestvennogo razvitija [Theory and Practice of Social Development], 2, 46-49.

Beck, U. (2000). Risk Society: Towards a different modern. Moscow: Progress-Tradition.

Belik, A. (1993). Psihologicheskaja antropologija. Istorija i teorija [Psychological anthropology. History and theory]. Moscow: Miklukho-Maklay Institute for Ethnology and Anthropology.

Bourdieu, P. (2001). Practical Sense. Moscow: Institute of Experimental Sociology; Saint Petersburg: Alteiya.

Department of Peoples Rep. Sakha (Yakutia) (2012). Information materials on interethnic and interfaith relations. Yakutsk: Dani Almas.

Egorov, A., Makarova A. (2008). Kross-kulturnye osobennosti moralnyh predstavlenij [Crosscultural characteristics of the moral concepts]. Vestnik Severo-Vostochnogo federalnogo universiteta [Herald of the North-Eastern Federal University], 5(4), 71-78.

Ganopol’skii, M., Litenkova, S. (2005). Tjumenskij frontir (metodologicheskie zametki) [Tyumen frontier (Methodological notes)]. Vestnik Tjumenskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta [Bulletin of the Tyumen State University], 4, 187-192.

Giddens, A. (2011). Consequences of modernity. Moscow: Praxis.

Gumilyov, L. (2008). Istorija kak forma dvizhenija energii [History as a form of motion energy]. Moscow: AST.

Ilinova, N. (2015). Ponimaniye komplimentarnosti Lva Gumilyeva kak factor v issledovanii mezhetnicheskikh vzaimodeistviy [Understanding complementarity of Lev Gumilyov as a factor in the research of interethnic interaction]. Sotsialno-Gumanitarnyie Znaniya [Socially-Humanitarian Knowledge], 9, 118-127.

INAB №5. (2012). Sociologicheskij otvet na “nacionalnyj vopros”: Primer Respubliki Bashkortostan [The sociological answer to the “national question”: the case of the Republic of Bashkortostan]. Moscow: Institute of Sociology, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.isras.ru/publ. html?id=2459

INAN №4. (2012). Identichnost i konsolidacionnyj resurs zhitelej respubliki Saha (Jakutija) [The identity and resource consolidation inhabitants of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia]. Moscow: Institute of Sociology. Retrieved from http://www.isras.ru/publ.html?id=2461

Kurgan, G.I. (2016). Uchenie o komplimentarnosti v jetnologii L.N. Gumileva [The doctrine of complementarity in Ethnology Gumilev]. Retrieved from: http://www.mosgu.ru/nauchnaya/publications/2007/professor.ru/Kurgan_GI

Malakhov, V.S. (2014). Kulturnye razlichija i politicheskie granicy v jepohu globalnyh migracij [Cultural differences and political borders in the era of global migration]. Moscow: New Literary Review.

To cite this article: Mikhailova V. V., Nadkin V. B. (2016). Ethno-confessional identity and complimentarity in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 9(1), 74-83.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.