Stigma Towards Depression in the Workplace

Abstract

Objective: The goal of this research was to examine the effect of stigma on employing a job candidate with a known mental illness, such as depression.

Background: Prior research established that negative stigmatizing attitudes towards mental illness affected employment discrimination. We hypothesized that participants would be less likely to hire a person with depression than someone without a mental illness.

Design:. A total of 162 undergraduate students from Glendon College were randomly assigned to one of two conditions where they were asked to read a short scenario listing qualifications and characteristics of a job candidate and answer a series of questions. The two questionnaires were identical except that one mentioned a diagnosis of depression and the other did not. We measured the likelihood that the participant would hire the candidate.

Results: The findings obtained were consistent with prior research and our hypothesis; the participants were significantly less likely to hire the candidate with a diagnosis of depression.

Conclusion: It appears that even in populations of highly educated people, we find instances of stigma towards mental illness. As these findings are not generalizable to the population at large, more research is required using a broader range and real-life situations.

Received: 15.07.2018

Accepted: 06.06.2019

Themes: Personality psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2019_3/Psychology_3_2019_3-12_Selezneva.pdf

Pages: 3-12

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2019.0301

Keywords: depression, stigma, employment, mental illness, clinical psychology, social psychology

Introduction

The aim of this study was to examine the stigma related to mental illness and how it affects employability for people afflicted with depression. Participants were asked to decide how likely they would be to hire a job candidate after reading one of two short paragraphs describing the candidate, in one of which a diagnosis of depression was mentioned whereas, in the other it was not.

In 2015, 43.4 million adults in the US were diagnosed with a mental illness (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017). Statistics Canada released results from a mental health survey from 2012, which stated that 10.1% of the Canadian population (15 years and older) reported symptoms associated with a mental disorder (Statistics Canada, 2012; The Daily, 2013). Of that

10.1 %,major depression is the mostcommonly reported type of mental health illness and affects roughly 3.2 million Canadians (Statistics Canada, 2012, The Daily, 2013). A global cross-sectional survey rated depression as the first most taxing disease for higherincome countries and the third most taxing disease globally (Lasalvia et al.,2013).

People diagnosed with a mental illness face innumerable challenges in their daily lives. These difficulties include stigma, which can be defined as “The negative social attitude attached to a characteristic of an individual that may be regarded as a mental, physical or social deficiency” (VadenBos, 2015). The stigma surrounding mental illness has been distinguished by two relevant dimensions: self-stigma and public stigma. Self-stigma occurs when people with mental illness internalize stereotypes, apply these attitudes to themselves, and suffer diminished self-esteem and lessened self-efficacy (Corrigan, Watson & Barr, 2006). Public stigma refers to the attitudes and beliefs of the general public towards people with mental illness (Link, 1987).

Although public and self-stigma are intertwined, for the purposes of this research we focused solely on public stigma.

Public stigma can be detrimental to obtaining employment for someone with a mental illness; stigma has a deleterious impact on obtaining good jobs (Link, 1987; Bordieri &Drehmer, 1986). Employment discrimination has been stated as the most recurrent type of stigma experienced by those with a mental illness (Stuart, 2006). The nature of a person’s disability is a crucial determinant in the way this person will be perceived and treated by others (Stone & Colella, 1996). In a model done by Stone and Colella, physical disabilities and psychiatric disabilities served as a classic contrast (Stone & Colella, 1996), because research has shown that people with a physical disability face less discrimination in the workforce than those with a mental illness (Mendel et al., 2015). In one study where human resources professionals were given a choice to hire an applicant with either a physical disability (“uses a wheelchair”) or an applicant with a mental disability (“takes medication for a depressive illness”), 87.7 % chose the candidate with the physical disability (Koser et al., 1999). Consistently, evidence suggests that hiring someone with a physical disability is favorable, but what is the employment situation for applicants who are diagnosed with a mental illness?

Research using hypothetical situations, such as presenting participants with fictitious scenarios of a person with a mental illness, and asking them to answer questions regarding their employability, has shown that people with a history of mental illness are significantly less likely to be hired than other candidates (Berven & Driscoll, 1981; Rickard et al., 1963; Stone & Sawatzki, 1980). Misconceptions and stigmatizing attitudes towards people who have undergone psychiatric treatment has also been found in real-world employment situations (Drehmer & Bordieri, 1985; Farina & Felner, 1973). However, there are only a few studies that have examined employers attitudes toward hiring someone with a common mental illness, such as depression. In one such study, graduate students enrolled in personnel administration courses, expressed that an individual who had been hospitalized in the past for depression could not attend work consistently, handle work pressures, or meet high-level job responsibilities (Berven& Driscoll, 1981). Research has shown that gender has a significant influence on the perception of someone with a mental illness and that men and women hold different attitudes towards mentally ill people. It has been claimed that women are more tolerant and accepting of people who have been diagnosed with a mental illness (Cook & Wang, 2010; Hinkleman & Granello, 2003; Mann & Himelein, 2004).

One study showed a decrease in stigmatizing attitudes towards people with depression after being exposed to a public awareness campaign, however, these effects were not long lasting. After retesting two years later with no further exposure to the campaign, the experimenters discovered that attitudes had reverted to similar results from the pre-test (Dietrich et al., 2010). These findings demonstrated that prejudicial attitudes towards mental illness can change when people are consistently educated and made aware of stigma. For this reason, we wanted to examine if undergraduate students, who are consistently educated on related topics, would have prejudiced attitudes towards employing someone with a known mental illness, such as depression.

Prior research suggests that discrimination towards someone with a known mental illness is prevalent in the workplace across varied situations. We hypothesized that participants who were told that the job candidate had a mental illness would report being less likely to hire the candidate than the participants who were not told that the job candidate had a mental illness.

Method

Participants

We randomly recruited 162 undergraduate students from Glendon campus. Some research showed that women tended to have fewer stigmatizing attitudes than men. Thus, to maintain group equivalence, we recruited an even number of men and women. (n=81; M=20.8 years old, SD=3.4 40 males & 41 females) were informed that the job candidate had a major depressive disorder, and the other half (n=81: M=20.36, SD=3.44; 40 of males & 41 females) were not.

Materials

The consent form stated who we are and why we were conducting this experiment. It explained the given task and the time it took to complete it. The form clarified that the participant was under no obligation, could decline to answer any questions, and could withdraw at any time. It also stated that all information would be kept anonymous and confidential, and that there would be no risks to the participants.

Questionnaires (attached at Appendix A). There were two questionnaires, each consisting of a one paragraph fictitious scenario in which a man named John was applying for a position as a sales representative. The position of the sales representative was chosen because it was the most common occupation in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2017). In the scenario, John’s experience, education, and characteristics were listed. The qualities of the candidate were chosen in such way that contained both positive and negative traits for the position. This was done in order to portray the applicant in a more realistic way and moreover, to make it harder for the participants to figure out the real goal of our research. The content of both scenarios was identical except that in one questionnaire it was mentioned that John had been diagnosed with depression, and in the other questionnaire there was no mention of a diagnosis of depression.

The three questions that followed the paragraph were identical in both questionnaires. The third question, “If you were the employer, what is the likelihood that you would hire John?” was our target question, the only one the responses to which we analyzed to measure the attitudes of stigma. We designed the other two questions as camouflage to keep the participant from guessing the true aim of our study. We measured the target question by using the Likert Scale and asked the participant to mark an X in one of six places along the scale. The scale measurements were from “Very Unlikely” (1) to “Very Likely” (6). We chose six places in the scale to avoid the tendency to want to pick the middle value and to force the participant to make a choice in one direction or the other.

Debriefing notes (attached at Appendix A). It was necessary for us to use passive deception in this study so that we could accurately measure the attitudes of stigma. If the participants had known that the goal of this research was to measure stigma, it might have influenced their responses. Thus, we stated in our consent form that the purpose of our research was to study hiring trends for the next generation, which was not the entire truth. We were, in fact, measuring whether they would be likely to hire someone diagnosed with depression. For this reason, we debriefed the participants by handing them a thank you note including our contact information after participation.

Procedure

We printed an even number of questionnaires per condition (depression or no depression). The depression questionnaires were divided into two equal piles, and the no depression questionnaires were divided into two equal piles. One pile of the depression questionnaires was added to one pile of the no depression questionnaires. They were then shuffled so as to avoid us having any knowledge of which participant would receive which conditioned questionnaire, thus, avoiding us imparting any of our own expectations onto the participants. Then, we put them in an envelope labelled ‘M’ for males, and the same procedure was followed with the remaining halves of the two questionnaires, except they were put in an envelope labelled ‘F’ for females. We printed copies of the consent form and our debriefing notes, which we cut into strips.

We stood outside the cafeteria of Glendon campus, where there tends to be a lot of foot traffic, and asked students to participate in our research study and receive a candy for participation. If they agreed, we handed them the consent form and requested them to read it carefully. Once completed, we asked them if they had any questions and if they understood the form. If the potential participant confirmed that they understood and agreed to participate, we handed them a questionnaire from the appropriate envelope and a pen.

After the participant returned the questionnaire, we added it to a new envelope either labeled F for females or M for males and handed them one of our thank you/debriefing notes and a candy.

Results

The dependent variable measured the participants likelihood of hiring a job candidate by asking them to mark an “X” on a Likert scale from (1) “Very Unlikely” to (6) “Very Likely”.

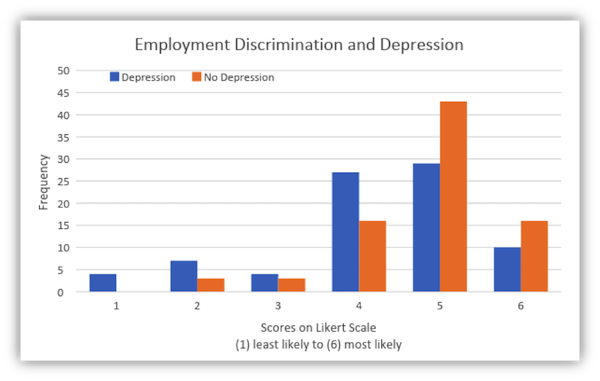

A one tailed independent-measure t-test revealed that the participants were significantly less likely to hire the candidate with depression than the candidate without (t(160)= -3.30, p < 0.01, see Figure 1). The mean score (M = 4.23, SD = 1.29) in the experimental condition where depression was mentioned was significantly lower than the mean score (M = 4.81, SD = 0.92) from the control condition where depression was not mentioned. The potential range was the same for both conditions (R = 6). The observed range for the experimental condition where depression was mentioned (R = 6) was larger than the range for the control condition where depression was not mentioned (R = 5).

Figure 1. Likelihood of hiring the candidate where a diagnosis of depression was mentioned vs. hiring a candidate with no mention of depression.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to measure the effects of stigmatizing attitudes held towards someone with a known mental illness, such as depression, on employment. Prior research on this subject suggests that stigma towards mental illness exists in the workplace and translates into employment discrimination in multiple forms. Consistent with prior research, participants in the current study were significantly less likely to employ the candidate with a diagnosis of depression than the candidate who did not have a diagnosis of depression. These results supported our hypothesis. Offering a candy as incentive may encourage people who normally would not participate in a research study like ours to volunteer. We believe this strengthened the internal validity of our study by reaching a more varied section of the target population.Although our results were significant, the external validity of this study is limited. These findings are not generalizable to the entire population, as undergraduate students only represent a small sector of the population. Also, in large part, undergraduate students have not held positions in which hiring possible job candidates would be in their job description and conceivably, were not able to realistically base any judgments from their own life experiences.

Another potential threat to the current research is the possibility that the participants were less likely to hire the candidate with depression, not necessarily because of the diagnosed mental illness, but due to the concern that the person suffering from depression might underperform the job responsibilities. Nevertheless, even if participants choice was based on the assumption discussed above, it still shows that the students perception of people with mental illness is distorted, meaning they hold the belief that the individuals with depression will not work as well as people without that mental illness, and that was the main idea we intended to address in this paper.

Fictitious scenarios generated similar results to studies where real-world workplace situations were assessed (Drehmer &Bordieri, 1985; Farina & Felner, 1973). Even when the choice between the candidate with a mental illness was compared to that of a candidate with a physical illness, significant results showed discriminating attitudes towards the candidate with mental illness (Koser et al., 1999). This further illustrates that there is little acceptance of those afflicted with depression and other mental illnesses in the workforce.

We have seen from studies that people with higher levels of education were less likely to hold stigmatizing attitudes towards those with depression (Cook & Wang, 2010). Other studies showed a decrease in stigma after being educated through awareness campaigns (Dietrich et al., 2010). If we found stigma towards mental illness among a population of highly educated students at a university with a large psychology program, what might we find in the general population? Considering this, it would be good to conduct longitudinal studies in North America comparable to those conducted in Germany where awareness campaigns were shown to reduce the stigma of mental illness over short periods of time (Dietrich et al., 2010).

Conclusion

It follows that more research where education and awareness of mental illness being reinforced in a multitude of ways is important in the possible reduction of employment discrimination towards those afflicted. Research of this type conducted in real-life employment situations in all employment sectors is important. In our study, the hypothetical job position described was that of a sales representative, as it is the most commonly held position in Canada. An important question to ask next would be if there are differences in stigma towards job candidates applying for a position as a lawyer or police officer compared to a fast food worker or laborer? Is employment discrimination towards mental illness similar across all sections of the workforce? The next steps could be to conduct a longitudinal study in which human resources professionals, in varied employment sectors, are tested before and after being exposed to awareness campaigns or educational seminars in their communities or workplaces. These are important questions to answer as depression affects a large percentage of the population and interferes with productivity in the workforce.

References

Berven, N.L., & Driscoll, J.H. (1981). The effects of past psychiatric disability on employer evaluation of a job applicant. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 12, 50-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0095571Bordieri, J., Drehmer, D.(1986). Hiring decisions for disabled workers: looking at the cause. J Appl Soc Psychol, 16, 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1986.tb01135.x

Cook, T.M., & Wang, J. (2010). Descriptive epidemiology of stigma against depression in a general population sample in alberta. BMC Psychiatry, 10, 11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-29

Corrigan, P.W., River, L.P., Lundin, R.K., Wasowki, K.U., Campion, J., Mathisen, J., et al.(2000).

Stigmatizing attributions about mental illness. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(1), 91-102. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(200001)28:1<91::AID-JCOP9>3.0.CO;2-M

Corrigan, P.W., Watson, A.C., Barr, L. (2006). The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social Clinical Psychology, 25, 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.875

Dietrich, S., Mergl, R., Freudenberg, P., Althaus, D., & Hegerl, U. (2010). Impact of a campaign on the public's attitudes towards depression. Health Education Research, 25(1), 135-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/her/cyp050

Farina, A., & Felner, R. (1973). Employment interviewer reactions to former mental patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 82, 268-272. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0035194

Hinkelman, L. & Granello, D.H. (2003). Biological sex, adherence to traditional gender roles, 1 and attitudes toward persons with mental illness: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 25(4), 259-270. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.25.4.tglx0uudjk7q5dpk

Koser, D.A., Matsuyama, M., & Kopelman, R.E. (1999). Comparison of a physical and a mental disability in employee selection: An experimental examination of direct andmoderated effects. North American Journal of Psychology, 1(2), 213-222. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/619537625?accountid=15182

Lasalvia, A., Zoppei, S., Van Bortel, T., Bonetto, C., Cristofalo, D., Wahlbeck, K., Thornicroft, G. (2013). Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination reported by people with major depressive disorder: A cross-sectional survey. The Lancet, 381(9860), 55-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61379-8

Link, B.G. (1987). Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review, 52, 96–112. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095395

Mann, C.E., & Himelein, M.J. (2004). Factors associated with stigmatization of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 55(2), 185-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.55.2.185

Mendel, R., Kissling, W., Reichhart, T., Bühner, M., & Hamann, J. (2015). Managers' reactions towards employees' disclosure of psychiatric or somatic diagnoses. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 24(2), 146-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S2045796013000711

National Institute of Mental Health, Any Mental Illness (AMI) Among Adults. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/any-mental-illness-ami-among-adults.shtml

Rickard, T.E., Triandis, H.C., & Patterson, C.H. (1963). Indices of employer prejudice toward disabled applicants. Journal of Applied Psychology, 47, 52-55.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0041815

Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0465-01. Mental health indicators (2017). Retrieved from http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1051101

Statistics Canada. Labour in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census (2017). Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171129/dq171129b-eng.htm?HPA=1

Stone, C.I., & Sawatzki, B. (1980). Hiring bias and the disabled interviewee: Effects of manipulating work history and disability information of the disabled job applicant. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 16, 96 - 104 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(80)90041-X

Stuart, H. (2006). Mental illness and employment discrimination. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19(5), 522-526. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.yco.0000238482.27270.5d

The Daily (2013). Retrieved from: http://www.apns.ca/documents/dq130918a-eng.pdf

VandenBos, G.R. (Ed.). (2015). APA dictionary of psychology (Second Edition). American Psychological Association. Retrieved from: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/york/reader.action?docID=3115092

To cite this article: Selezneva E., Batho Denise. (2019). Stigma Towards Depression in the Workplace. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 12(3), 3-12

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.