Social Psychology of Instability within Organizational Reality

Abstract

Since modern organizations inevitably face constant changes in internal and external environment, can anything be done in order for the strategy of changes to become “proactive” and to prevent naturally determined crisis situations and recession? Featuring empirical data, the article discusses the possibility of sociopsychological research in the situation of instability. Among other aspects, there is suggested an answer to the question of whether social psychology can help a person to realize his/her identity in professional and organizational environments. Moreover, a number of fixed behavioral patterns observed in situations of changes are examined specifically.

Themes: Organizational psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2012/bazarov.pdf

Pages: 271-288

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2012.0016

Keywords: organizational changes, managerial identity, business play simulation exercises, ways of response to changes

According to G.M. Andreeva, any situation of instability is accompanied by such transformations of public consciousness as breaking stereotypes, reconsideration of values, experiencing identity crisis, changing the world vision (Andreeva, 1997). Among the specifics of social instability, in addition to a sharp and radical nature of social changes, the scholar outlines a possible unbalance of the latter, in other words a possible shift in their course and pace, inconsistencies in the degree of their radicalism in different spheres of social life (economics, politics, culture, types of human relationships). In this regard, a special attention is given to the study of social mindsets in the context of changes. There is a correlation between a change in social mindsets and the nature of personality dispositions: the more complex the social object which evokes a specific disposition in a personality, the more rigid the disposition. As set forth by Andreeva, it is necessary to analyze the change in social mindset from two perspectives: the essence of true-to-life social changes affecting this level of dispositions, as well as transformations of the individual’s active position caused not just “in response” to a situation, but by force of circumstances emerging from the development of such person. (Andreeva, 2000)

E. Schein believes that there are two forces influencing a person who is undergoing a period of instability and transformations: learning-related anxiety, and survival-related anxiety. In this respect, four types of fear can be distinguished: 1) the fear of being temporary incompetent (a conscious estimation of personal incompetence in a new situation); 2) the fear of punishment for being incompetent; 3) the fear of “losing one’s self ” (“internal confusion”, the lack of correlation between the usual way of thinking and feeling, and a new situation); 4) the fear of losing one’s position in a group (Schein, 1999).

For transformational changes to appear, the survival-related anxiety should dominate over the learning-related anxiety, while overcoming the learning-related anxiety should lower the survival-related anxiety. In this case, survival-related anxiety is the driving force, while the learning-related anxiety is the restraining factor. In order to cope with one’s (personal) own resistance to everything connected with instability, certain help is needed to decrease his learning-related anxiety. One can achieve it in a number of ways: by creating a convincing image of the future; formal training; involving a student; informal training of appropriate teams; drilling, practicing with feedback; introducing positive role models, consecutive systems and structures; imitation and identification as an alternative to the trial and error method.

What questions do mark today the major pathway to teaching social psychology of instability in respect to organizational reality? It’s likely that there are quite a few. But let us concentrate on three of them:

- Once the process of acquiring self-identity takes place both in professional and organizational management spheres, can social psychology help a person to identify him/herself in professional and organizational environment?

- It would be fair to suppose that subjects possessing different individual characteristics and mindsets will demonstrate different set ways to behave in the environment of undergoing changes. But can modern social psychology describe these ways?

- Since modern organizations inevitably face constant changes in an internal and external environment, can anything be done in order for the strategy of changes to become “proactive”, in other words can this strategy allow for a new “wave” in organizational development to prevent naturally determined crisis situations and recession?

Graduation research papers and PhD dissertations written under our supervision and presented hereafter can offer several answers to the questions above.

Socio-psychological research in managerial identity

The research field of managerial problems and organizational development has a high demand for applying concept models and methodical tools, which have been developed in social psychology to solve practical tasks. The process of acquiring self-identity takes place in both professional and organizational management spheres, so one of the tasks of social psychology is to help a person to identify him/herself in the professional and organizational environment.

The process of expansion and complication of the social reality, which is being actively created by a human, the “constructor”, brings about new types of identity, which is commonly defined as the issue of “multiplicity” or “fragmentariness”. Thus, new problems have to be solved in the area of research in self-identification. One of the approaches deals with professional identification. The professional environment is a key social space where a person can identify himself. Managers and executives represent a special socio-professional group in modern Russia, and their professional socialization and identity has distinct specific traits. Acquiring proficiency in “management” as a code for educational standards, obtaining the status of a self-sufficient profession, building the professional community and culture of business education and scientific research – all these are milestones for creating this special space reserved for “executives”. The space being understood both as external, connected with the development of social understanding of executive management, the development of organizational executive cultures, as well as internal, targeting the individual who perceives himself as an executive, a professional, a personality. In this respect, the issue of managerial identity, being positioned at the crossroads of several fields of study in social psychology, represents a topical problem for research. Social psychology of management provides a framework of categories for the problem, which includes managerial activities, determinants of specific stylistic features of management, etc. Organizational psychology studies the context in which this type of identity takes shape and develops. Psychology of social cognition is of immediate interest in terms of examining the specifics of structure of the world image and of self image, as well as in terms of new research data on organizational social cognition. Social psychology of personality, which is more or less connected with the study of identity, determines the boundaries and traditions of the present range of problems. Therefore, the crossroads spirit of this issue is defined by its nature as well as by the structural distinctions of the managerial identity phenomenon itself. The fact is that this type of identity has a number of “substrata”. On the one hand, it is considered traditional to recognize the presence of two aspects being part and parcel of the identity: one is a personal aspect (personalized, pertaining to one person), and the other is a social aspect (pertaining to a group). When studying the problem of identification within the framework of social cognition psychology, G.M. Andreeva defines two types of identification: the personal type as a person’s self-identification in physical, intellectual, and moral perspective; and the social type as a person’s self- identification by relating oneself to a specific social group.

M.Yu. Kuz’mina revealed in a PhD dissertation (Kuz’mina, 2004)

that managerial identity has three dimensions: the content plain, the estimation plain, and the time plain. Moreover, these are mainly subjective self-identification characteristics that determine the specific traits of managerial identity.

Figure 1. Types of personal identification in executives and film directors

Figure 2. Types of personal identification and strategies of actualization of the managerial identity in students

The quantitative and qualitative data analysis according to the method called “Who am I as an executive?” revealed several types of personal identification that characterize managerial identity (see fig.1, 2). (1) The “role” type is defined by conciseness (5–40 words), and prevalence of nouns pertaining to different roles. This type has a special sub-category: an “association” type, represented by a professional group of film directors and connected with personification and the use of metaphors and images (metaphors constituting 8.77% of all film directors’ statements); (2) the “personality” type represents personal identification via terms describing personal traits in the form of adjectives and participles; there is also a “role-personality” type characterized by prevalence of personal self-identification traits. The common feature of the two types is lack of categorical differentiation: the number of categories that are composed of relevant statements does not exceed five; (3) the “reflexive” type boasts a variety of categories, cognitive complexity, depth of reflec tion, presence of estimation component, and is more rich in words in comparison with the other types. This type more often embraces indicators of both achieved and diffused categories of identification; (4) the “combined” type is the most common; it combines the “role” and “personality” self-identification characteristics, together with several aspects of the “reflexive” type. A group of students demonstrated such types of personal identification that were never found in a group of reallife executives; (5) the “impersonal” type is characterized by lack of “I” and by prevalence of statements in second person, or enumeration of skills and responsibilities, and abstract topics; (6) the “stereotype” personal identification is characterized by abundance of terms pertaining to academic management (“the leader of formal and informal groups”, “mastering the art of motivation”, etc), use of set linguistic patterns, and commonly accepted statements about what an executive should be. Thus, managerial identity can be found even in those who are not subjects of managerial activities.

A group of students was interviewed on what they took into consideration when completing a task. The answers showed that five strategies were applied: “me in the future”, “significant other”, “ideal image”, “personal perspective”, “knowledge and experience”. Therefore, the locus of managerial identification can be internal, in other words, self-oriented (“I”), or external, oriented on an image of another person (“he”, the executive) and on collective perceptions. It can be graphically represented as follows.

The other strategies have an external locus: “Who is he and how can he describe himself?”; it is an image of an ideal executive, social understandings and stereotypes that become apparent in the absence of managerial experience and distinct personal identification. “What is he?”; these are impersonal statements, a list of managerial functions and responsibilities. Thus, we can talk about a perception phenomenon related to sociopsychological processes of social cognition.

The managerial identity has external and internal orientation.

- The internal aspect is composed of personal self-descriptive traits of character (socio-emotional, professional, moral qualities and those of a leader); social roles (interpersonal, functional and formal, the ones associated with status and position, sexual, and universal); self-descriptions in connection with executive skills, functions and a management style; statements with respect to the sphere of motivation and needs (motivation of achievements, of power, of the need to self-actualize, to be respected, acknowledged); conditions and feelings.

- The external orientation in the process of self-identification comes with a reference to topics that are crucial in the managerial context: interpersonal relations, and problems of existence, organization and profession.

The time scale for managerial identity is introduced by such categories as the retrospective managerial identity (“I was – in the past”), the possible (or potential) managerial identity (“I will be – in the future”): “me as a possible ideal variant”, “me as a possible real-life variant”, as well as a possible organizational identity.

The content plain of the managerial identity is determined by sociopsychological specifics of profession (Bazarova, 2007). Thus, the cooperative- artistic type of cooperative efforts of film directors determines evidence of the emotional component in the managerial identity, as well as the broadness and differentiation of role repertoire for the representatives of this professional group.

A person who is not a real-life executive can still have an actualized managerial identity. Several strategies depicting such actualization were singled out: “me in the future”, “significant other”, “ideal image”, “personal perspective”, “knowledge and experience”. In this particular case, we are dealing with a perception phenomenon related to socio-psychological processes of reflection, identification, attribution, to social stereotypes and understandings.

The content plain of the managerial identity is also determined by the organizational identity: a) the reflection of organizational problems corresponds to an internal perceptive organization model and to the content of the preferred managerial role; b) the managerial identity and organizational commitment are deemed to be under reciprocal influence.

Socio-psychological features pertaining to styles of response to changes

Nowadays the problem of personal and individual factors in accepting changes is widely presented in theoretical and practical publications. Nevertheless, the data available is a mixture of rather discrete construct types and empirical data. There exist several types of constructs for revealing how changes are accepted: adaptability of an individual (Kuznetsova, 2005), tolerance towards uncertainty (Belinskaya, 2006), psychological barrier against something new (Prigozhin, 1989), generalized innovation disposition (Sovetova, 2000). The question still remains open: how are these constructs interconnected, and is it possible to single out any crucial features and to design such a model of styles of response to changes that would unite numerous constructs of studying individuality in the environment of changes. A significant number of traits common to those who participate in the process of changes should be analyzed, thereby bringing about the necessity to determine the most crucial traits and to come up with a typology to anticipate actions of the participants.

It would be fair to suppose that subjects possessing different individual characteristics and mindsets will demonstrate different set ways of behavior in the environment of undergoing changes (Bazarova, 2006). By extracting differential individual peculiarities and reactions, and by uniting them into groups – in other words, by singling out styles and types of response to changes – it is possible to overcome the above-mentioned controversy. In order to solve this problem, M.P. Sycheva applies in her dissertation paper a typological approach that relies on the description of a typical (or an average variant) representative of a group of people related to a certain type.

The analysis of different approaches to determination of distinctions in participants of the process of changes permits coming up with the following various criteria to suggest the typology: a degree of acceptance of changes (Rogers, 2003), key patterns of behavior (Zhuravlev, 1993), a cluster of mindsets and ways of thinking (Musselwhite & Randell, 2004), personalized traits (Burlachuk & Morozov, 2007). A solution to the problem of anticipating actions is seen in combining two approaches, namely, a simultaneous analysis of social mindsets towards changes, and an analysis of typical behavior. We believe that this controversy can be best shown by means of such concept as “style”. Some authors (e.g. see Merlin, 2007) argue that style is a linking chain between a person and a social environment and one of the major mechanisms of human adaptation to any activity.

A comprehensive view on the problem of behavior in the environment of undergoing changes suggests bringing together the following key approaches: the mindset-oriented approach, the typological approach, and the dynamic approach. In order to design a generalized model, which would allow describing and anticipating a person’s behavior in response to changes. It is important, first of all, to describe characteristic traits of his/her mindset towards the changes, secondly, to identify typical means, approaches and tactics of person’s actions in the environment of undergoing changes, and thirdly, to describe the most characteristic emotional and cognitive reactions he/she experiences in such situations. These components can provide for a universal typology of responses to changes. We propose this theoretical construct as a style of response to changes, which should be understood as preference of certain ways of interaction between a person and a situation of changes, with said preference being expressed through emotional, cognitive and behavioral responses to changes (Bazarov & Sycheva, 2010).

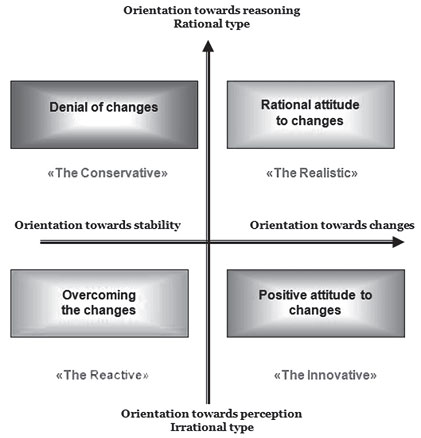

Figure 3. Model of a typology of response towards changes

The orientation towards innovation and stability corresponds to tolerance towards uncertainty, which reveals itself through the degree of awareness of uncertainty about the environment, through the intensity of worrying about the environment, and through the tendency to react to uncertainty in a specific way.

The orientation towards reasoning corresponds to the tendency to perceive the world as organized and predictable. The orientation towards perception corresponds to the tendency to perceive the world as flexible and spontaneous, where there is no decision on the final variant until the very last moment.

An experiment-based research discovered four styles of response to changes: “innovative”, “conservative”, “reactive” and “realistic”. The summarized results of the research allow us to compare descriptions of each style. We are going to dwell upon each of them in detail.

The “innovative” people accept changes and are ready to be triggers of changes. They get emotionally involved in any new ideas, even if they do not believe that those are really necessary. They are a success at the initial stage of changes: they actively generate ideas, look for solutions to problems. When the situation becomes more stable, they are willing to implement the decisions made, and they are unlikely to sabotage the changes. They prefer to solve problems with an uncertain result or ambiguous interpretation, problems requiring new solution approaches. In their opinion, the changes are for the better. Resistance to changes can be overcome through search of benefits for themselves and for the company through self-persuasion in the need for changes. In the changing environment, they expect their supervisor to be active (to make decisions quickly and to shift to the implementation mode rapidly). Experimenting, excitement, openness can be named among characteristic responses and behavior in the changing environment. Atypical responses would be stress, denial of existence of changes, desire to continue work according to previous rules.

The “realistic” people will support and accept changes only if they consider them really necessary. They prefer innovations to stability; nevertheless they are not ready to accept any idea and would rather make sure that it works in practice before accepting it. They can initiate changes if they need them and realize their necessity. These people are reason able when working under new conditions. They combine readiness for innovations typical of the “innovative” people with rationality typical of the “conservative” people. A preferred type of tasks (results) is clear-howto- do tasks, if such tasks are viewed as really crucial. They do not resist changes and eagerly accept new approaches and ideas. In a situation of uncertainty and sudden changes, they usually make decisions immediately and start to act right away, concentrate on a problem and think of how it can be solved. Resistance to changes is overcome through analysis of the situation (counting advantages and disadvantages of changes, reasons for changes, and possible variants of behavior in a situation). In the changing environment, they expect their supervisor to communicate (to give precise and clear information on current events, to be specific and truthful in explaining what result is expected from the changes). Openness and the desire to take risks belong to characteristic responses and behavior in the changing environment. Abnormal responses would be lack of confidence in themselves, stress, denial of existence of changes, passivity.

The “conservative” people hardly ever see any need for changes. They prefer stability to changes. To make such people accept changes, it is important to provide them with convincing reasons in favour of changes. It is deemed difficult to convince the “conservative” representatives of the necessity of changes, since the old order is by default viewed better than something new. And even if they realize the necessity of changes, they are likely to habituate to this idea for a long period of time. Once the changes have been introduced, this type of people continues to work according to the same rules as before. They are inclined to analyze a situation of changes, classify separate facts and observations into a rational scheme. When they encounter a problem, they try to fully understand the whole essence of it and tend to keep a distance from actions to be able to thoroughly scrutinize the situation and observe it from different aspects. Their preference goes to problems that have a single solution, in which the result is clear and intelligible. So far as their behavior during changes is concerned, they apply standard proven methods to solve problems, prefer all procedures to go according to a designated plan, as a rule, they think everything over, prefer to act in a familiar way.

How do they overcome resistance to changes? They tend to accept changes as something that was bound to happen and accept a situation passively; they believe that changes will finally turn out for the

better; they switch over to other activities (reading, sports), abstract themselves and keep distance from the situation. A typical response to changes includes fear, anxiety, lack of confidence, denial of existing changes. They expect their supervisor to be active, confident, reasonable and dominant. The supervisor’s leadership is perceived as persistence, self-confidence, courage, quick wittedness, equanimity. Hope, adherence to former rules, denial of changes, can be named among their typical reaction, as well.

The “reactive” people perceive changes emotionally. They prefer stability to changes. To persuade them to accept changes, it is crucial to highlight their personal benefit, to empathize with them, to help them overcome stress and discomfort. The emotional response is highly apparent, which is sometimes manifested in the form of explicit confrontation. They prefer to start solving problems when it is clear how to accomplish the task, when there is some experience in finding solutions. Their response to changes: they need some time to accept changes, they have to spend a lot of energy and vigor to accept innovations and changes. When finding themselves in a changing environment, they may be irritated and emotional, anxious, worried and constrained: their attitude can be a restraining factor for enthusiasm of others. They usually actively protest, which can take the form of sabotage or attempts to persuade others that there is no need for changes. A characteristic response and behavior in a changing environment includes lack of self-confidence, denial of existence of changes, frustration.

The conducted research allowed singling out and describing groups of people that have some common traits and simultaneously differ from each other. The description of the styles makes it possible to anticipate behavior of different groups of people involved in undergoing changes depending on their individual psychological features.

Like any typological approach, singling out these styles may possess its opportunities and constraints. Thus, the major benefit of the typological approach is its quick and easy-to-use source of knowledge that generates a precise and eloquent result. However, the weak point of the typology is skipping fine details typical of everybody’s individuality.

At the same time, the study of a personality’s response to the changing environment has produced more new questions rather than gave exhaustive answers to the initial ones. In particular, we believe that future research should target the correlation of individual-personal characteristics, styles of response to changes, and such parameters of the changing environment as readiness of personnel, availability of resources (Bazarov, 2007), scale of changes (Ross & Nisbett, 1999), nature of changes, principles of corporate culture existing within the company.

Corporate play activities and preparedness for organizational changes

Nowadays, it is impossible to ignore trends of transformation when considering long-term planning. Modern companies inevitably face constant changes in internal and external environments. The foregoing gives rise to the following question: how can introduction of changes impact the general cycle of a company’s development? Can anything be done for the strategy of changes to become “proactive”, or in other words, can this strategy allow for a new “wave” in organizational development to prevent naturally determined crisis situations and recession? Such proactive strategy can be implemented during the phase of change planning.

When describing models of the process of organizational changes, most authors analyze the problem of overcoming resistance from the personnel caused by the need to accept changes as inevitable and introduced by an external intervening source. This unnatural and harsh process of introducing changes can bring about many difficulties, become unacceptable for the majority of employees, and subsequently get ineffective.

After analyzing a well-known model of changes suggested by Virginia Satir, according to which integration (the process of accepting changes) starts inevitably in a situation of “chaos” produced by the changes, we decided to formulate the issue in another way. Is it possible to come up with such a planning phase that would ensure that decisions on changes were not only accepted, but were even desired, designed, and introduced by all company employees involved in this process?

In order for it to happen, it is essential to create such conditions when each participant of the change process would have an option to choose freely without the fear to take risks and without feeling limited in his desire to experiment and suggest new ideas and solutions. E. Ovchinnikova in her graduation paper made an attempt to provide such conditions by means of specifically designed corporate play activities.

In this respect, the connection of a game with the future comes to the foreground as its main function is to prepare employees for the future, which can be done through training skills, shaping mindsets, modeling socially important relationships and situations, etc. The possibility to choose freely and to identify yourself in game are conditions for independent changes that may relate to values, mindsets, activity skills, perception of the world, behavior. The game broadens the consciousness, enriches it, and develops its flexibility and reflexivity. This being mentioned, it is important to note how powerful the creative potential of the game is. Evolving radically new and unique ideas, activity types and procedures is an essential condition to successfully devise and develop changes.

An organizational structure of corporate activities serves as an independent variable. The latter is set through, firstly, corporate play activities (sample groups), and secondly, through corporate non-play activities, i.e. group discussions (control groups).

Dependent variables were:

1. The degree of moral readiness for changes, which was evaluated by test subjects after group decisions were taken. Four parameters of evaluation were as follows: certainty about the decision made, chances of finding a better solution, satisfaction from the decision, readiness to implement the decision.

2. The creativity of the devised group decisions that is determined on the basis of the following key factors: freshness, complexity, emotional plain, representation (conformity to the task).

The creativity assessment procedure was based on the method of creative story telling developed by Rainbow Project Collaborators from the PACE Center, Yale University. The experimental effect was reached in both cases by statistical comparison of two random values of dependent variables taken from sample and control groups (Kornilova, 2002).

An auxiliary variable was the individual predisposition of a test subject to changes. This variable was assessed via the 16-factor Kettle personality questionnaire (form C, 105 questions), the results of which were employed to determine personal indices according to Factor Q1. Factor Q1 is characterized by two polarities: “flexibility” (radicalism), i.e. predisposition to experiments and innovations, the desire to reconsider the existing principles, and “rigidness” (conservatism), i.e. the desire to preserve the existing standards, principles, traditions, as well as doubts about new ideas, denial of the need for changes.

To assess the individual predisposition to changes, the test subjects were asked to analyze five specifically chosen situations that suggested a choice either in favour of changes or in favour of stability.

The sample groups and the control groups had the best possible composition of test subjects that were equal according to the following criteria: sex and age, dominating managerial function within the company (heterogeneous composition, as every group had representatives of different roles), individual predisposition to changes (Factor Q1 value, and the results of choice made by test subjects when they evaluated the five suggested situations).

With the degree of individual predisposition to changes being equivalent in all groups, it was possible to control the influence of the auxiliary variable on the results of the experiment. To assess reliability of the values reflecting the creativity of group decisions, the consistency index of expert opinion was calculated (Chronbach’s alfa coefficient).

The composition of the test groups was as follows: 53 test subjects within 10 small groups counting 5-6 subjects each. There were 29 females and 24 males aged from 20 to 35 among them. The sample groups counted 27 subjects, the control groups included 26 subjects. The selection was represented by senior university students (6 groups), interns and young professionals working in Russian medium-size and major companies (4 groups).

The results of the conducted research demonstrate that corporate play activities affect internal readiness of the participants to changes. It should be noted that the readiness of the participants to implement decisions in the changing environment is closely connected with their satisfaction of the decision made. Simultaneously, as far as corporate non-play activities (group discussions) are concerned, the readiness to implement decisions in the changing environment depends on their awareness of the fact that they took the right decision. We should mention among other important results that corporate play activities simulating the changing environment and an uncertain image of the future encourage more creative solutions distinguished in that they are more unique and richer in emotional terms.

The research results served as a basis for the following design philosophy for creating an efficient model of corporate play activities, the model being intended to prepare employees for organizational changes.

The processes simulated during corporate play activities should be conditional so that the participants could learn how to overcome the fear of taking wrong decisions and not to deprive them from the opportunity to experiment on searching for solutions to complete the task.

Corporate play activities should feature a situation of uncertainty. Unless the participants go through a certain number of discussion phases and thoroughly study every suggested idea, it would be impossible to precisely assess alternative ways of solving a problem. It contributes to comprehensive assessment and reflection of the situation itself, as well as facilitates corporate creativity.

The teams of those participating in corporate play activities should be heterogeneous from the perspective of internal corporate managerial roles. When making decisions on the executive level, the difference in orientation, character, and degree of readiness to changes existing in representatives of different managerial roles facilitates emergence of substantially different views on the situation under discussion. It contributes to deeper understanding and more thorough assessment of the problem, and stimulates dynamic processes in a small group when a solution should be reached through consensus during discussions and negotiations.

It is also important to create favorable conditions for the development of participants’ emotional attitude to their role, since such conditions will foster involvement in the play process. The participants should feel free to determine their personal identity, which increases their satisfaction from the decision they have made together with their colleagues, and determines the growth in the degree of internal readiness to implement said decision.

Corporate play activities should not be limited to a single groupgenerated solution of a task. Instead, it should provide an opportunity to further work the problem out, and it should be systematic, since one of the effects of play activities is participants’ recognition of personal potential to find new better solutions in the future.

References

- Andreeva, G.M. (1997). Psihologia sotsialnogo poznaniya [Psychology of Social Cognition]. Moscow: Aspekt-Press.

- Andreeva, G.M. (2000). Sotsial’naya psihologiya [Social psychology]. Moscow: Aspekt-Press. Bazarov, T.Yu. (2007). Psihologicheskie grani izmenyayushhejsya organizatsii [Psychological aspects of an organization undergoing changes]. Moscow: Aspekt-Press.

- Bazarov, T.Yu., & Sycheva, M.P. (2010). Lichnostno-situatsionny’e faktory’ prinyatiya izmenenii [Personal and situational aspects of accepting changes]. In Sovremennaya sotsial’naya psihologiya: teoreticheskie podhody’ i prikladny’e issledovaniya [Modern Social Psychology: Theoretical Approaches and Applied Research], 1 (6), 39-48.

- Bazarova, K.T. (2006). Fenomen raspredelennogo liderstva: sotsialno-psihologicheskaya refleksiya novoj situatsii [The phenomenon of distributed leadership: sociopsychological reflection of new situation]. In Novye v psihologii [New in Psychology]. (pp. 48-61). Moscow: Fakultet psikhologii MGU im. M.V. Lomonosova.

- Bazarova, K.T. (2007). Osobennosti obucheniya vzroslyh [Peculiarities of adult education]. Menedzher po personalu. [Human Resources Manager], 2, 42-49.

- Belinskaya, E.P. (2006). Identichnost’ lichnosti v usloviyah sotsial’ny’h izmenenij [Personal identity during social changes]. Disserattsiya d-ra psihol.nauk [Dissertation of doctor of science]. Moscow, MGU im. M.V. Lomonosova.

- Burlachuk, L.F., & Morozov, S.M. (2007). Slovar’-spravochnik po psihodiagnostike [Reference dictionary of psychodiagnostics]. St. Petersburg: Piter.

- Zhuravlev, A.L. (1993). Sotsial’naya psihologiya lichnosti i maly’h grupp: nekotory’e itogi issledovaniya [Social psychology of personality and small group: some research data]. Psihologicheskii zhurnal [Journal of Psychology], 14 (4), 4-15.

- Kornilova, T.V. (2002). Eksperimental’naya psihologiya: teoriya i metody’ [Experimental psychology: theory and methods]. Moscow: Aspekt-Press.

- Kuznetsova, O.V. (2005). Individual’no-tipologicheskie faktory’ adaptivnosti lichnosti [Individual typological factors of personality’s adaptivity]. Dissertatsiya kand. psihol. nauk [PhD dissertation]. Odessa, Yuzhnoukrainskii gos. pedagogicheskii universitet im. K.D. Ushinskogo.

- Kuz’mina, M.Yu. (2004). Sotsial’no-psihologicheskie faktory’ upravlencheskoj identichnosti rukovoditelya [Social-psychological factors of management identity of director]. Dissertatsiya kand.psihol.nauk [PhD dissertation]. Moscow, MGU im. M.V. Lomonosova.

- Merlin, V.S. (2007). Sobranie sochinenij [Complete works]. Perm: Prikamskii sotsialnyi institut.

- Musselwhite, C., & Randell, J.R. (2004). Dangerous opportunity: making change work. Philadelphia, Xlibris Corporation.

- Prigozhin, A.I. (1989). Novovvedeniya: stimuly’ i prepyatstviya [Innovations: stimuli and obstacles]. Moscow: IPL.

- Ross, L., & Nisbett, R. (1999). Chelovek i situatsiya: uroki sotsial’noj psihologii [Man and situation: lessons of social psychology]. Moscow: Aspekt-Press.

- Sovetova, O.S. (2000). Osnovy’ sotsial’noj psihologii innovatsii: uchebnoe posobie [Basics of social psychology of innovation: a tutorial]. St. Petersburg: Saint-Petersburg University.

- Rogers, E.M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.). New York: Free Press.

- Schein, E.H. (1999). The Corporate Culture Survival Guide. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

To cite this article: Bazarov T.Yu. (2012). Social Psychology of Instability within Organizational Reality. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 5, 271-288

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.