Tolerance, Empathy, and Aggression as Factors in Compliance with Rules of Online Communication by Russian Adolescents, Young Adults, and Parents

Abstract

Background. Internet psychology has changed its research focus from describing the Internet as a separate space, with continuous interaction between offline and online communication, to exploring socialization in the world of mixed online/offline reality. This paper deals with the psychological and user activity factors of communication on the Internet in comparison with offline communication.

Objective. To differentiate the role of user activity, difficulties with regulating and expressing aggression, empathy and tolerance in compliance with online communication rules.

Design. The study included 1,029 adolescents aged 14-17, 525 adolescents aged 12-13, 736 young adults aged 17-30, and 1,105 parents of adolescents aged 12-17. Participants assessed how likely they are to follow communication rules online and offline, and reported their user activity level; they filled out the Chen Internet Addiction Scale, Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire, Davis Multidimensional Empathy Questionnaire, and Tolerance Index.

Results. It was shown that adolescents in general are a “risk group” for noncompliance with communication rules (“Internet etiquette”), but this is due to their general propensity not to follow any rules. Both in adults and in adolescents, failure to follow online communication rules is related to difficulties with aggression regulation, tolerance, empathy, and a low level of propensity for Internet addiction.

Conclusion. A difference between online and offline communication is related not to difficulties with regulation of aggression (anger and hostility), but to a lack of empathy and tolerance, and signs of Internet addiction.

Received: 20.02.2019

Accepted: 04.03.2019

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2019_2/Psychology_2_2019_79-93_Soldatova.pdf

Pages: 79-93

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2019.0207

Keywords: communication rules; online; adolescents; intergenerational comparisons; tolerance, empathy; anger; hostility; propensity to Internet addiction

Introduction

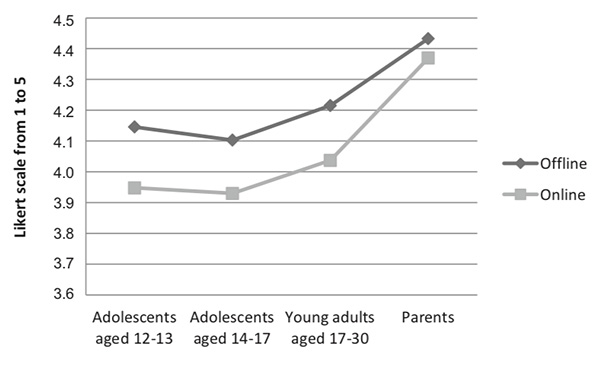

Internet psychology has made its way over several decades from describing the Internet as a separate virtual world, through an understanding of continuous offline and online interaction, to defining concepts of digital socialization, digital competence, and digital citizenship as crucial elements of socialization processes, the formation of social competence and citizenship (Mossberger, Tolbert, & McNeal, 2008; Soldatova, Rasskazova, & Nestik, 2017). By becoming full members of the information society (including online), modern adolescents face and solve a series of different life tasks, in particular related to their relations with other people and specific aspects of communication. There is empirical evidence that, as part of this process, prosocial behavior prevails over antisocial behavior in online communication among modern adolescents (Erreygers, Vandebosch, Vranjes, Baillien, & De Witte, 2017). However, direct comparison (Soldatova & Rasskazova, in press) of compliance with communication rules online and offline (which obtained consistent results for nine rules) indicates that there are specific features of communication on the Internet: Adolescents, young adults, and parents all less often follow online communication etiquette than they do offline social norms. In addition, the younger the respondents are, the greater is the discrepancy between their online and offline behavior (see Figure 1). In other words, adolescents comprise a distinctive “risk group” with regard to online communication. From the psychological point of view, the key question is what determines whether a person behaves responsibly and considerately toward others on the Internet, and what causes a discrepancy between online and offline behavior. To put it another way, what defines the willingness to do things online that you do not allow yourself offline?

Figure 1. Compliance with communication rules online and offline in different groups.

We can suggest several psychological factors promoting online communication that is rude, inconsiderate, or non-reciprocal (i.e., not based on a mutual relationship).

First, at the very least, difficulty with emotion regulation, including aggression, might be a non-specific factor in violating communication rules both online and offline. The roles of hostility as a personal disposition and of anger as a feature of emotional experience and expression of aggression may be different (Buss & Perry, 1992). According to empirical data, anger in young adults is related to both signs of problematic Internet use and trouble communicating with one’s mother and father (Say & Durak, 2016), and in adolescents it is related to a propensity for Internet addiction (Kim, 2013).

Secondly, we can suppose that such factors as empathy and tolerance play a key role in online communication, due to their close connection to a considerate, responsible attitude toward another person, the ability to see things from another person’s perspective and to empathize, including if this person is from a different culture, nationality, or social group. However, can we reckon empathy and tolerance to be independent factors, not reduced to the features of aggression regulation? It is known that empathy and tolerance are closely connected to aggression, including online (Machackova & Pfetsch, 2016). For instance, an intervention to reduce stereotyping and group distortion on the part of Christian students and Islamic students was effective in large part due to changes in emotion regulation, in particular because the students started to use fewer words expressing anger and sadness (White, Abu-Rayya, Bliuc, & Faulkner, 2015).

Finally, despite all the ambiguity of the term “Internet addiction” (Griffiths, 2005), we can suggest that failure to comply with online communication rules is associated with specific user activity, especially to problematic Internet use. The literature allows us to identify two opposite opinions: (a) Extensive use of the Internet may lead people to feel impunity, difficulty with empathy, and hence a greater propensity to violate reciprocity and politeness in online communication. With problematic Internet use (a propensity for addiction), to the extent that a person abandons other important life tasks, including communication with friends, negative communication will also extend to this person’s offline activities. (b) Extensive online activity may promote better understanding of other users, and thus more civilized communication with them. Thus, according to Japanese data, active Internet users have a more tolerant attitude toward strangers and representatives of other nationalities (Seebruck, 2013).

Unfortunately, the studies we have mentioned are few and do not answer several questions that are important both practically and theoretically. To which aggressive features is adherence to rules online related more closely: to anger as a propensity to express emotions or to hostility as a personal disposition toward the world? Do empathy and tolerance have their own effect by promoting adherence to rules online, after statistical control for aggression? Are user activity features important in whether a person follows online communication rules, or are these effects totally reduced to the effects of common psychological variables—aggression, empathy, tolerance? And if they are important, are we exclusively talking about pathological user activity (Internet addiction and problematic Internet use) or is frequency and intensity of online activities by itself connected to a propensity to violate communication rules? Finally, are these associations similar for different generations and which of them are specific to modern adolescents—a special “risk group” that violates Internet etiquette?

The purpose of this study was to differentiate among the roles of user activity (including a propensity to Internet addiction), difficulties with regulating and expressing emotions (anger and hostility), and empathy and tolerance, in compliance with online communication rules and in greater unwillingness to follow the rules online as compared to offline. Our hypotheses were as follows:

1. Empathy and tolerance as factors in adopting a responsible attitude toward another person are associated with greater willingness to follow communication rules online, including after statistical control for difficulties with regulation of aggression (anger and hostility) and following communication norms offline.

2. Specific features of user activity (primarily a propensity for Internet addiction) are additional specific predictors.

3. User activity and difficulties with aggression regulation are more closely related to willingness to follow communication rules online in adolescents than in young adults and parents, whereas the effects of empathy and tolerance are maintained at all ages.

Methods

Participants

The respondents were 1,029 adolescents aged 14–17 (47.0% boys), 525 adolescents aged 12–13 (45.7% boys), 736 young adults aged 17–30 (40.8% men, mean age 23.33±3.90), and 1,105 parents (19.4% men) of adolescents aged 12–17. Parents’ age ranged from 28 to 65 (mean age 41.21±5.63). Respondents represented 17 cities of 8 federal districts: Southern (Rostov-on-Don, Volgograd), Volga (Kazan, Kirov), Siberian (Kemerovo, Novosibirsk), Far Eastern (Magadan, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Khabarovsk), North Caucasian (Makhachkala, Vladikavkaz), Northwestern (Saint Petersburg, Vologda), Central (Moscow, Moscow Region), and Ural (Tyumen, Yekaterinburg).Procedure

Data was collected by the Foundation for Internet Development, supported by the Russian Association for Electronic Communication. The survey used the personal interview method and questionnaires for each age group. A university network was used for selecting interviewers who had the relevant professional level for conducting the study: Lomonosov Moscow State University, Saint Petersburg State University, Volgograd State Social and Pedagogical University, Dagestan State Pedagogical University, Khetagurov North Ossetian State University, Kazan Federal University, Vyatka State University, Ural State Pedagogical University, University of Tyumen, National Research Tomsk State University, Novosibirsk State University, Pacific National University, and Vitus Bering Kamchatka State University.

Sixty-eight experienced interviewers/psychologists were selected for conducting the survey. Employees of the Foundation for Internet Development and Lomonosov Moscow State University’s Department of Psychology monitored the interviewers’ work.

Adolescents and young adults took part in the survey only if they use the Internet. Parents took part in the survey only if they had children aged 12–17 who use the Internet.

Measures

Findings were made by using the following methods:

-

The assessment of followingcommunication rules online and offline was subjective. Experts/psychologists formulated nine common rules of interpersonal communication describing norms for courtesy, responsibility, consideration, and mutuality: “Be polite to people you are talking to”, “Conduct yourself in accordance with the rules of the place you are in”, “Express your thoughts in a polite and civilized manner”, “Share only verified information”, “Share your knowledge and respect others’ input into an exchange of knowledge”, “Regulate the process of expressing your emotions—your words and actions may hurt other people”, “Have respect for other people’s private lives and personal boundaries”, “Do not use your authority and abilities to harm others”, “Be tolerant of the shortcomings of those around you”. Respondents were asked to assess how often they follow each rule “In real life” and “On the Internet”, on a Likert scale from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“Constantly”). We then estimated the subjects’ overall willingness to follow communication rules offline (Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80–0.86 for the different groups) and online (0.84–0.88).

-

The assessment of user activityincluded two items about time spent on the Internet during the week and on the weekend (options were “less than one hour”, “1–3 hours”, “4–5 hours”, “6–8 hours”, “9–12 hours”, and “more than 12 hours”). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85 in both adolescent groups, 0.80 for young adults, and 0.65 for parents.

-

The Chen Internet AddictionScale(Chen, Weng, Su, Wu, & Yang, 2003) adapted by V.L. Malygin and K.A. Feklisov (Malygin et al., 2011). The questionnaire consists of 26 statements to which four answer options weregiven (“not at all”, “a little bit”, “partially”, “absolutely”). It includes the following scales: compulsive symptoms, withdrawal symptoms, tolerance, intrapersonal problems, health problems, and time management. An overall index defining propensity for Internet addiction was used.

-

The Buss-Perry AggressionQuestionnaire(Buss & Perry, 1992; Enikolopov & Tsibulsky, 2007) was used for assessing the overall level of hostility and difficulties controlling it. Only indices for the scales of hostility as a general attitude, and anger as an expression of aggression, were used. The physical aggression scale was not used, as it cannot be applied directly to online activities.

-

The ToleranceIndexQuick Questionnaire(Soldatova, Kravtsova, Khukhlaev, & Shaigerova, 2008) is used to assess tolerance, including ethnic tolerance (attitude toward representatives of other ethnic groups and attitudes about intercultural interaction), social tolerance (attitude toward such social groups as minorities, criminals, and mentally ill people), and tolerance as a personality trait. In this study, an overall index was used.

-

The DavisMultidimensional Empathy Questionnaire(Interpersonal Reactivity Index, Davis, 1983; Budagovskaya, Dubrovskaya, & Karyagina, 2013) was used to asses empathy, with four scales translated into Russian: perspective taking, fantasy, empathic concern, and personal distress. We used the overall index of empathy (Cronbach’s alpha 0.71 for adolescents, 0.56 for young adults, and 0.65 for parents).

Adolescents aged 12–13 did not fill out the tolerance and empathy assessment measures, and thus their results were included only at the stage of correlation analysis.

Results

Associations Between Compliance with Communication Rules and Psychological Factors in Adolescents, Young Adults, and Parents

Compliance with communication rules both online and offline does not depend on the average number of devices used for accessing the Internet and is almost unrelated to overall user activity—only for adolescents was average time spent on the Internet during the week and on the weekend slightly negatively correlated to following rules online. Negative correlations between following rules and signs of Internet addiction are more remarkable and reach the significance level in all the groups, which is in line with the concept that it is not online activity by itself, but rather problematic activity, that may be connected to violation of communication rules.

People who are more tolerant, have a high level of empathy and a lower level of anger and hostility, more often abide by communication norms, both online and offline. In parents these associations are slightly weaker than in adolescents and young adults.

It is apparent (see Table 1) that correlations with online and offline communication are almost identical, which is no surprise considering the high correlation between these variables (r = 0.63–0.77 in different groups). In order to get a variable indicating unique differences in following communication rules online, independent of what happens offline, a regression analysis was made (separately in each group). In this analysis, following communication rules online was a dependent variable and following them offline was an independent one. For each respondent, an index of “residual” variance (so-called error variance) was maintained—i.e. those of his/her features in compliance with communication rules online that are not reduced to what happens offline and cannot be predicted on the basis of offline behavior. In fact, this index defines the difference between following rules offline and online. It can be seen from Table 1 that “genuine” willingness to follow rules online is not associated with anger and hostility, but slightly associated with tolerance, empathy, and the absence of signs of Internet addiction.

Table 1

Associations between aggression, empathy, tolerance, user activity, and compliance with communication rules online and offline: Correlation analysis in different age brackets

|

Compliance with rules |

Anger |

Hostility |

Tolerance |

Empathy |

User activity |

Internet addiction |

|

|

Adolescents |

Compliance with communication rules offline |

-0.15** |

-0.12** |

0.22** |

0.20** |

-0.04 |

-0.19** |

|

Compliance with communication rules online |

-0.15** |

-0.10** |

0.22** |

0.24** |

-0.10** |

-0.19** |

|

|

Unique variance – compliance with rules online |

-0.05 |

-0.02 |

0.09** |

0.14** |

-0.10** |

-0.07* |

|

|

Adolescents |

Compliance with communication rules offline |

-0.17** |

-0.15** |

– |

– |

-0.12** |

-0.28** |

|

Compliance with communication rules online |

-0.17** |

-0.15** |

– |

– |

-0.09* |

-0.21** |

|

|

Unique variance – compliance with rules online |

-0.08 |

-0.06 |

– |

– |

-0.02 |

-0.05 |

|

|

Young adults |

Compliance with communication rules offline |

-0.25** |

-0.24** |

0.21** |

0.25** |

-0.02 |

-0.16** |

|

Compliance with communication rules online |

-0.24** |

-0.24** |

0.25** |

0.23** |

-0.01 |

-0.22** |

|

|

Unique variance – compliance with rules online |

-0.07* |

-0.08* |

0.14** |

0.07 |

0.02 |

-0.15** |

|

|

Parents |

Compliance with communication rules offline |

-0.13** |

-0.13** |

0.19** |

0.13** |

-0.02 |

-0.13** |

|

Compliance with communication rules online |

-0.07* |

-0.08* |

0.21** |

0.19** |

-0.02 |

-0.17** |

|

|

Unique variance – compliance with rules online |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.10** |

0.13** |

-0.02 |

-0.12** |

|

Note. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Aggression, Empathy, Tolerance, and User Activity as Predictors of Online Communication: Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis

To test our hypotheses about the role of empathy and tolerance as being independent of aggression regulation, and about the role of problematic Internet use in groups of adolescents aged 14–17, young adults, and parents, hierarchical regression analysis was performed with groups-moderators (Chaplin, 2007). The group variable was coded by two binary variables (parents and older adolescents in contrast to young adults—“young adults” was a reference group); the variables of compliance with communication rules offline, anger, hostility, empathy, tolerance, Internet addiction, and user activity were centered (Chaplin, 2007). Variables-moderators were calculated as pairwise products of binary variables of a group with all the others. The analysis was conducted twice—with and without statistical control for following rules offline. In other words, the first model was aimed at finding general psychological and user predictors of compliance with online communication rules, and the second one at finding predictors of why people do not follow the rules particularly online, in contrast to offline (i.e., the difference between offline and online behavior). Variables that were added at each stage of hierarchical analysis are shown in Table 1.

Without statistical control for compliance with the rules offline, the overall regression model explains 21.4% of variance of the variable “compliance with the communication rules online”. In accordance with the model, in all groups the significant predictor of failure to follow rules online is anger, and not hostility. In adolescents aged 14–17 and young adults, anger is a more important factor than it is with parents (comparison of simple regressions: in adolescents β = -0.21, p < 0.01, in young adults β = -0.16, p < 0.01, in parents β = -0.02, p > 0.10). In all the groups, tolerance and empathy are related to greater willingness to follow communication rules, and it seems as though their effects are not reduced to each other and do not depend on respondents’ age bracket. In all respondents, Internet addiction, but not user activity, is related to failure to follow communication rules online. Only for adolescents aged 14–17 can we suggest that following rules online depends on overall user activity (in contrast to problematic Internet use): Whether or not adolescents have signs of addiction, the more time they spend on the Internet, the less they follow communication rules (comparison of simple regressions: in adolescents β = ‑0.12, p < 0.01, in young adults β = -0.02, p > 0.10, in parents β = 0.04, p > 0.10).

If we examine online and offline differences (i.e., the predictor of a “gap” between online and offline behavior), then the only predictors of following communication rules online that are common for all respondents are tolerance and low level of Internet addiction. Two additional factors distinguish older adolescents from young adults: higher level of empathy (comparison of simple regressions: in adolescents β = 0.11, p < 0.01, in young adults β = 0.03, p > 0.10, in parents β = 0.07, p < 0.01) and lower level of user activity (comparison of simple regressions: in adolescents β = -0.07, p < 0.01, in young adults β = 0.01, p > 0.10, in parents β = 0.01, p > 0.10).

Reviewing the separate stages of both regression analyses allows us to specify the answers to the questions asked above (see Table 2):

-

Parents tend to follow both communication rules in general and online communication rules; adolescents tend to violate communication rules in general. However, this effect in adolescents is not only connected to the digital world, as after statistical control for willingness to follow communication rules offline, this effect disappears.

-

If we take features of emotion regulation as primary psychological predictors, then both anger and hostility are related to violation of communication rules, though the role of hostility is more obvious in young adults than in adolescents, and parents are somewhere in between (comparison of simple regressions: in adolescents β = 0.07, p > 0.10, in young adults β = -0.13, p < 0.05, in parents β = -0.06, p > 0.10). Furthermore, measuring in the offline communication model leads to disappearance of the effects of both anger and hostility—in other words, these are non-specific factors that are more related to communication in general than to explaining online and offline differences. Moreover, even in relation to general compliance with communication rules, the effect of anger is constant, whereas the effect of hostility disappears when the other variables are introduced.

-

Tolerance and empathy are related to better compliance with communication rules. However, only tolerance predicts polite communication specifically online, whereas, after statistical control for offline behavior, the role of empathy is retained only in adolescents.

-

High user activity has a specific connection to the worst compliance with communication rules online; however, it is problematic Internet use (signs of addiction) that is relevant. The effect of user activity is only observed in adolescents.

Table 2

Psychological predictors of following communication rules online: Results of hierarchical regression analysis

|

Stages of hierarchical regression analysis: independent variables |

Compliance with communication rules online without control for offline |

Compliance with communication rules online with control for offline |

||

|

β |

ΔR2 |

β |

ΔR2 |

|

|

Stage 1 |

||||

|

Offline communication rules |

- |

9.1%** |

0.77** |

60.9%** |

|

Offline communication rules × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

- |

-0.03 |

||

|

Offline communication rules × Parents |

- |

-0.01 |

||

|

Adolescents aged 14–17 |

-0.08** |

-0.01 |

||

|

Parents |

0.25** |

0.10** |

||

|

Stage 2 |

||||

|

Anger |

-0.15** |

2.6%** |

-0.03 |

0.2%* |

|

Hostility |

-0.13* |

-0.03 |

||

|

Anger × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

-0.03 |

-0.03 |

||

|

Anger × Parents |

0.07 |

0.04 |

||

|

Hostility × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

0.14** |

0.06 |

||

|

Hostility × Parents |

0.03 |

0.02 |

||

|

Stage 3 |

||||

|

Empathy |

0.17** |

6.7%** |

0.03 |

1.0%** |

|

Tolerance |

0.11** |

0.06* |

||

|

Empathy × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

0.05 |

0.05* |

||

|

Empathy × Parents |

-0.01 |

0.02 |

||

|

Tolerance × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

0.02 |

-0.02 |

||

|

Tolerance × Parents |

0.03 |

0.00 |

||

|

Stage 4 |

||||

|

Internet addiction |

-0.18** |

2.6%** |

-0.11** |

0.6%** |

|

Internet addiction × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

-0.01 |

0.02 |

||

|

Internet addiction × Parents |

0.00 |

0.00 |

||

|

Stage 5 |

||||

|

User activity |

-0.02 |

0.6%** |

0.01 |

0.2%** |

|

User activity × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

-0.07* |

-0.06** |

||

|

User activity × Parents |

0.01 |

-0.01 |

||

|

General model |

||||

|

Offline communication rules |

- |

21.4%** |

0.73** |

62.9%** |

|

Offline communication rules × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

- |

-0.04 |

||

|

Offline communication rules × Parents |

- |

0.00 |

||

|

Adolescents aged 14–17 |

-0.04 |

0.01 |

||

|

Parents |

0.21** |

0.09** |

||

|

Anger |

-0.11* |

-0.02 |

||

|

Hostility |

-0.06 |

0.02 |

||

|

Anger × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

0.02 |

-0.01 |

||

|

Anger × Parents |

0.08* |

0.05 |

||

|

Hostility × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

0.05 |

0.00 |

||

|

Hostility × Parents |

0.02 |

0.00 |

||

|

Empathy |

0.19** |

0.04 |

||

|

Tolerance |

0.09** |

0.06* |

||

|

Empathy × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

0.06 |

0.05* |

||

|

Empathy × Parents |

-0.01 |

0.03 |

||

|

Tolerance × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

0.00 |

-0.02 |

||

|

Tolerance × Parents |

0.02 |

0.00 |

||

|

Internet addiction |

-0.18** |

-0.11** |

||

|

Internet addiction × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

0.01 |

0.04 |

||

|

Internet addiction × Parents |

0.00 |

0.00 |

||

|

User activity |

-0.02 |

0.01 |

||

|

User activity × Adolescents aged 14–17 |

-0.07* |

-0.06** |

||

|

User activity × Parents |

0.01 |

-0.01 |

||

Note. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Discussion

For this paper, the initial data (Figure 1) showed that as people get older, they not only tend more to follow the rules of communication, but their willingness to follow the rules online increases and gradually “catches up with” their offline behavior. Moderation analysis clarifies this result by showing that while in the case of adolescents we are talking about a general inclination to violate the rules (both online and offline), compared to young adults and parents, and the fact that this is not specific to the online world (it disappears after statistical control for offline behavior), with the parents we see a reduction of the discrepancy between the online and offline worlds compared to young adults and adolescents. This suggests that for an adult with established communication norms, the online world does not seem to be essentially new compared to the offline world. Note that a person with long-held beliefs and values is more likely to follow these beliefs online, even if violating them is to this person’s advantage and does not threaten negative consequences. On the other hand, we can see a discrepancy between offline and online behavior in young adults and adolescents. Although it is a constant discrepancy—it is not greater in adolescents than in young adults—it is more likely that the Internet is very good space where adolescents can “post” their general effort to resist rules and norms.

This raises the question of what factors (aggression regulation, tolerance and empathy, user activity features) may promote following rules and reduction of the discrepancy between offline and online behavior in adolescents. Are they universal or specific to adolescence?

The results of correlation analysis have shown that although adolescents who spend more time on the Internet are in general a little bit less oriented toward polite and respectful communication, even in these groups relationships are weak. That is why there are no grounds for assigning to the Internet on its own the role of a “destroyer” of communication rules. There is more reason to suggest that online communication depends on emotional features (anger and hostility) and communication features (tolerance, empathy), and among user activity factors, problematic (and not just any) Internet use is more important. As we have said, willingness to follow communication rules online and willingness to do so offline are more similar than different. Already at the stage of correlation analysis, the difference between online and offline communication is related not to difficulties with aggression regulation (anger and hostility), but to empathy, tolerance, and absence of signs of Internet addiction. In other words, difficulties with aggression regulation are more likely to be a general than a specific factor and to determine a person’s general attitude in any communication. On the other hand, tolerance and empathy may perform both general tasks to promote consideration and acceptance of other people and specific tasks in the online world, thereby reducing the discrepancy between online and offline behavior.

Moderation analysis allows us to specify these results (although, due to the correlation design of this study, unambiguous conclusions regarding cause-effect relations cannot be reached):

Role of aggression regulation. We can suggest that general willingness to follow rules is related to aggression regulation in all the groups, both in the form of disposition (hostility) and in the form of regulation of expressing aggression (anger). But only the effect of anger is retained after adding the other variables, and the effect of hostility is less expressed in adolescents than in young adults (where it is at the maximum). On the one hand, this suggests that the hostility is related to following communication rules not directly but, for example, through its association with Internet addiction, since it is the addition of this variable that reduces the effect of hostility, and the effect is clearly observed only in adolescence. Examination of this hypothesis requires a separate mediation analysis and a longitudinal study design. On the other hand, the effect of hostility appears to be generally less clear and less constant than the effect of anger. Anger and hostility are not related to the discrepancy between online and offline communication. Practically speaking, this means that interventions to improve aggression regulation are justified in adolescence (as in adulthood) if they are aimed at working with its expression rather than with general hostility. The effect of such interventions is unlikely to be specific to online communications. Hostility is likely to be seen as a potential target (also non-specific) of psychological work or as a sign of a risk group only in adolescence.

Role of tolerance and empathy. Empathy and tolerance allow us to predict compliance with the rules online, after statistical control for hostility and anger. In other words, showing consideration for other people, an ability to see from another person’s perspective and to empathize with this person, are related to politer and more reciprocal communication online, even in people with a high level of hostility and anger. Moreover, the discrepancy between online and offline behavior, which does not depend on aggression regulation, is specifically related to a low level of tolerance, and in adolescents it is also related to a low level of empathy. From our point of view, this result allows us to define a system of priorities for practical interventions. Thus, it can be assumed that even in case of difficulties with aggression regulation, psychological work aimed at the development of empathy and tolerance can be effective for improving online communication; its effect is not only general, but also specific in terms of reducing the discrepancy between online and offline behavior. In adolescents, where this discrepancy is at its maximum, the development of empathy becomes a “support” for the psychologist, in addition to tolerance.

Role of user activity and propensity for Internet addiction. Problematic Internet use (propensity for Internet addiction) is important for predicting both general willingness to violate communication rules online and a discrepancy between online and offline behavior. With regard to user activity, no such effect has been found: Willingness to violate communication rules online is more likely to be associated with signs of excessive use of the Internet, including the gradual sacrifice of other areas of life not related to addiction (Griffiths, 2010), rather than how much time a person spends on the Internet. However, it should be noted that there is an independent effect of user activity in adolescents; adolescents who spend a lot of time on the Internet more often violate communication rules online and have a greater difference between their online and offline indices. It is interesting that this effect does not support the idea that adolescents who use the Internet more often are more tolerant and thus more considerate to others (Seebruck, 2013). Practically speaking, this shows that in all psychological work aimed at improving online communication, an evaluation of whether there is Internet addiction should be made, and problematic Internet use itself is a target for intervention in all cases. In adolescents, spending a great deal of time every day on the Internet can be considered a risk factor, even if they deny signs of Internet addiction.

Conclusion

Adolescents in general are a “risk group” for not following Internet etiquette, but this is due to their general propensity not to follow communication rules. In fact, online indices “catch up with” offline indices only in the parents’ group, which suggests that in adulthood regulation of communication, both online and offline, is determined by stable and less context-dependent personal norms, values, and beliefs. In both adults and adolescents, the target for psychological interventions may be features of aggression regulation (but more likely expressed as anger than hostility as a stable disposition), developing tolerance and empathy, and overcoming the signs of Internet addiction. However, only tolerance, low propensity to Internet addiction, and—in adolescents—also empathy and a low level of user activity, are associated with reducing the discrepancy between online and offline communication.

Limitations

The limitations of this study are primarily in the characteristics of the sample. While the sample of young adults and adolescents is balanced by gender, the sample of parents was mostly women (80.6%). Respondents were residents of large cities. These sampling features may limit generalization of the results.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 18-18-00365).The authors express their appreciation for the help of all the specialists from different cities who took part in data collection and digitizing.

References

Budagovskaya, N.A., Dubrovskaya, S.V., & Karyagina, T.D. (2013).Adaptatsiya mnogofaktornogo oprosnika empatii M. Devisa [Adaptation of the Davis Multidimensional Empathy Questionnaire]. Konsultatsionnaya psikhologiya i psikhoterapiya [Consultation Psychology and Psychotherapy], 1, 223–227.Buss, A. H., & Perry M.(1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,63, 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452

Chaplin, W.F. (2007). Moderator and mediator models in personality research. In R.W. Robins, R.C. Fraley, & R.E. Krueger (Eds.),Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp.602–632). New York: The Guilford Press.

Chen, S.-H., Weng, L.-J., Su, Y.-J., Wu, H.-M., & Yang, P.-F. (2003). Development of a Chinese Internet Addiction Scale and its psychometric study. Chinese Journal of Psychology, 45(3), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1037/t44491-000

Davis, M. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,44, 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

Enikolopov, S.N., & Tsibulsky, N.P. (2007). Psikhometricheskiy analiz russkoyazychnoi versii Oprosnika diagnostiki agressii A. Bassa i M. Perri [Psychometric analysis of the Russian version of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire]. Psikhologicheskiy zhurnal [Psychological Journal], 1,115–124.

Erreygers, S., Vandebosch, H., Vranjes, I., Baillien, E., & De Witte, H.(2017). Nice or naughty? The role of emotions and digital media use in explaining adolescents’ online prosocial and antisocial behavior. Media Psychology, 20(3), 374–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1200990

Griffiths, M. (2010). The role of context in online gaming excess and addiction: Some case study evidence. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction,8, 119–125.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-009-9229-x

Griffiths, M.A. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use. 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359

Kim, K. (2013). Association between Internet overuse and aggression in Korean adolescents. Pediatrics International, 55(6), 703–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.12171

Machackova, H., & Pfetsch, J.(2016). Bystanders’ responses to offline bullying and cyberbullying: The role of empathy and normative beliefs about aggression. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12277

Malygin, V.L., Feklisov, K.A., Iskandirova, A.S., Antonenko, A.A., Smirnova, E.A., & Khomeriki, N.S. (2011). Internet-zavisimoe povedenie. Kriterii i metody diagnostiki [Internet addiction behavior. Criteria and diagnostic methods].Uchebnoe posobie [Training manual]. Moscow: MGMSU.

Mossberger, K., Tolbert, C.J., & McNeal, R.S. (2008). Digital citizenship: The internet, society, and participation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/7428.001.0001

Say, G., & Durak, B. (2016). The assessment of the relationship between problematic Internet use and parent-adolescent relationship quality, loneliness, anger, and problem solving skills. Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 29(4), 324–334. https://doi.org/10.5350/DAJPN2016290404

Seebruck, R. (2013). Technology and tolerance in Japan: Internet use and positive attitudes and behaviors toward foreigners. Social Science Japan Journal, 16(2), 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyt017

Soldatova, G. U., Kravtsova, O. A., Khukhlaev, O. E., & Shaigerova, L. A. (2008). Ekspress-oprosnik Indeks tolerantnosti [Tolerance Index Quick Questionnaire]. In G.U. Soldatova & L.A. Shaigerova (Eds.), Psikhodiagnostika tolerantnosti lichnosti [Psychodiagnostics of personality tolerance] (pp. 46–51). Moscow: Smysl.

Soldatova, G.U., & Rasskazova, E.I. (in press).Soblyudenie pravil obshcheniya onlain i oflain v raznykh pokoleniyakh: sravnenie podrostkov, molodezhi i roditeley [Compliance with communication rules online and offline in different generations: Comparing adolescents, young adults and parents].

Soldatova, G.U., Rasskazova, E.I., & Nestik, T.A. (2017).Tsifrovoe pokolenie Rossii: kompetentnost i bezopasnost [The Russian digital generation: Competence and safety]. Moscow: Smysl.

White, F., Abu-Rayya, H. M., Bliuc, A.-M., & Faulkner, N. (2015). Emotion expression and intergroup bias reduction between Muslims and Christians: Long-term Internet contact. Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.074To cite this article: Soldatova G. V., Rasskazova E. I. (2019). Tolerance, Empathy, and Aggression as Factors in Compliance with Rules of Online Communication by Russian Adolescents, Young Adults, and Parents. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 12(2), 79-93.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.