The Dynamic Personality: ‘Continuity Amid Change’

Abstract

Background. In psychology, analyzing the problem of personality is closely connected with the search for a methodology to describe personality in all its diversity. The dispositional approach, which is based on identifying stable personality traits, has resulted today in the dominance of a structural-functional approach. It has the advantage that it allows comparative analysis and the juxtaposition of specific personality characteristics inherent in the underlying construct, but it also has the limitation that it is inadequate for the study of personality as a dynamic structure, one capable of changing as the world around it changes.

Objective. To analyze and systematize the empirical studies of recent years in the field of personality psychology in order to identify and describe the principal trends in the study of the phenomenology of personality, reflecting distinctive features of human existence in the modern world.

Design. The method of research included a meta-analysis of reports (N = 1,149) from three European conferences on personality: the 17th European Conference on Personality (2014), Lausanne, Switzerland; the 18th European Conference on Personality (2016), Romania; the 19th European Conference on Personality (2018), Zadar, Croatia. We also describe the changeability of personality characteristics in the context of the individual’s life, on the basis of meta-analytical databases compiled by Roberts et al. (2006) and Wrzus et al. (2016).

Results. The results demonstrate the continuing domination of structural methodology in empirical studies of personality, despite the criticism to which it has been subjected. However, the number of studies of various aspects of dynamic personality processes is growing. Research reflecting the phenomenology of everyday life is expanding, as studies of daily human behavior, life events, and life situations are increasing proportionally. Researchers’ attention is being drawn to diverse contexts of life: the environment, culture, relationships. Data collection technologies are changing: Digital devices enable information about personality to be obtained online, tracking all the diversity of personality in different situations, its changeability and dynamism. Metadata indicate the changeability of personality traits that have long been considered stable: extraversion, emotional stability, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and agreeableness. The dynamics of personality traits are essentially determined by the context of a person’s life and vary depending on changes in that life. The continuity of these changes is processual and does not fit into the structural approach.

Conclusion. Modern personality psychology has contradictory trends. On the one hand, especially in empirical research, the traditional structural-functional paradigm for describing the personality remains influential, while attempts are made to improve it in response to criticism. On the other hand, an increasing number of studies are devoted to the study of real people in the real world, confronting the challenges of a changing world. A growing amount of empirical data describing the dynamic personality, changing in time and space, necessitates theoretical understanding and the search for a methodology relevant to the study of the changing personality.

Received: 31.08.2018

Accepted: 04.03.2019

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2019_2/psych_2_2019_3_Kostromina.pdf

Pages: 34-45

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2019.0203

Keywords: personality psychology, dynamic personality, structuralfunctional approach, processual approach

Introduction

Personality psychology had its start as a scientific field in the 20th century. Throughout its history, a variety of theoretical approaches and explanatory models have been proposed to describe the nature of personality, its structure, the determinants of its activity in various domains of life. Today, along with traditional problems in personality psychology, new issues are arising, one of the most important of which is how the changes in the modern world affect the personality.

The question of the changeability of the personality is not new to science, but there is increasing interest in it as the modern world becomes more and more dynamic.

In 1974, under the notable title Becoming modern, the results were published of a large-scale sociological study on changing people in a changing world (Inkeles & Smith, 1974). The authors call the task of explaining how people move from traditionalism to modernity, to a modern type of personality, the most important task of the social sciences. In 1994, the American Psychological Association published a collective monograph, Can personality change? (Heatherton & Weinberger, 1994). The works presented there reflect the traditional approach to the problem of “stability–changeability” and mainly follow the research schemata of developmental psychology and age psychology, which trace the changes in intellectual characteristics or personality traits at different age periods. The Journal of Personality recently published a special issue (2018) entitled “Status of the trait concept in contemporary personality: Are the old questions still the burning questions?” The editors believe that trait theory remains the most important scientific explanatory and research model. They note that, despite the resounding criticism to which it has been subjected, the trait theory approach is a continuously developing paradigm. The journal’s authors want to improve the traditional paradigm in personality psychology based on trait theory, which focuses on the stability of basic personality structures over time. Modern trait theory research is attempting to answer the question of how traits can be used to understand individuals, to predict their behavior, and to relate individual traits to human behavior overall and other processes. This question remains one of the primary ones: Research based on trait theory offers excellent opportunities for comparative analysis, but is inadequate in describing the psychological phenomenology of the individual unique personality [Giordano, 2017].

Modern personality psychology has reached the level of empirical research at which the amount of published data is tens or maybe hundreds of times greater than the number of works on theoretical interpretation of the results of that research and the development of methodology for studying personality, taking into account changed reality (Grishina et al., 2018).

An answer to the question of how to describe personality in today’s changing world requires theoretical understanding and cannot be obtained only by empirical research, which more and more confirms the need for new ways of describing the personality.

The purpose of this study is to systematize and provide a statistical synthesis of modern personality research so as to identify the main trends in this problem field, including key approaches that dominate the empirical research of recent years.

Method

The main research method was meta-analysis (see Dickerson & Berlin, 1992). The subject of the meta-analysis was scientific reports (N = 1,149) presented at the 17th, 18th, and 19th European Conferences on Personality (2014, 2016, 2018), as well as description of normative personality changes (113 samples with a total of 50,120 participants from age 10 to 100) and changes in personality traits in the life context,based on the meta-analytical databases of Roberts et al. (2006) and Wrzus et al. (2016).

Results

The meta-analysis revealed a number of trends characterizing changes in the problem field of personality psychology and approaches to its study.

Predominance of the Structural-Functional Approach to the Description of Personality in the Methodology of Empirical Research

The best illustration of the fact that “the structural approach has taken over the world” (Giordano, 2015) is the dominance of that approach, especially in empirical research, in the materials presented at major worldwide and European conferences on the subject of personality.

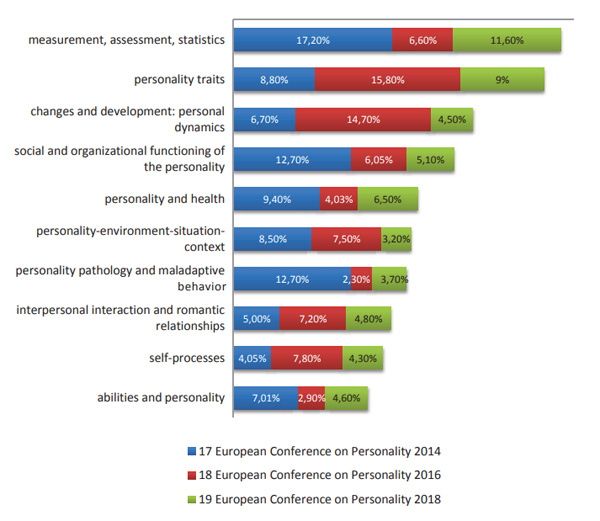

In the traditional areas of personality psychology, almost one fifth of the presentations at European conferences on personality from 2014 to 2018 were devoted to studies based on the use of factor models and personality questionnaires built upon them (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Comparative analysis of the topics of presentations at European Conferences on Personality (2014–2018).

Figure 1 shows clearly that despite proportional shifts in one direction or another, there is consistent priority for the percentage of submitted reports on personality traits and their intensity, as well as on various statistical models, measurement scales, and personality assessment instruments. Only at the 18th European Conference on Personality (2016), for the first time, was the amount of research on personality development and change almost comparable to the number of studies on personality structure and the intensity of individual personality traits, far ahead of the category “measurement and assessment of personality”. This shift revealed a tendency to reject the perception of the personality as a kind of static entity, in the structure of which individual traits change their intensity under the influence of age or social effects.

Yet at the 19th European Conference in 2018—the most recent scientific assembly in personality psychology—first place was again taken by reports on the measurement and assessment of various aspects of personality (11.6%). The share of statistical models, measuring scales, assessment instruments, validation of existing studies, new versions of questionnaires, etc. had almost doubled.

Expansion of the Problem Field of Personality Research and Increase in the Proportion of Studies of Everyday Behavior

The reports of the last three conferences (2014, 2016, 2018) allow us to reach a conclusion not only about changes in the topics that are becoming the subject of research to a greater or lesser degree, but also about gradually more differentiated content. Whereas in 2014, the 10 top fields excluded just a little more than 10% of the total reports, topics not included among the top 10 had reached 25% in 2016 and 34% in 2018.

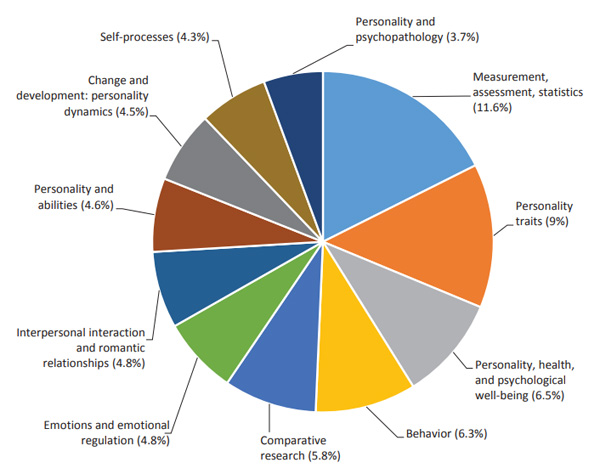

Overall, comparing the reports of the three recent European conferences, we can see how the interests of researchers are changing, primarily shifting their attention to phenomena that are as close as possible to a person’s real existence, to everyday experience (Fig. 2), the experience of prosocial behavior, innovative behavior, economic and cooperative behavior, organizational behavior and behavior in the family, relationships, and pleasant daily experiences (positive emotional impressions and maintaining relationships).

Figure 2. Distribution of topics at the 19th European Conference on Personality (July 17–21, 2018, Croatia)

In 2016, the key approach to personality research was Sam Gosling’s entreaty: “It’s time to study real people in the real world” (2016). The increase in the proportion of studies of the individual’s daily behavior and everyday experience clearly demonstrates that this call has been heard and that the psychology of everyday life is becoming one of the key areas of knowledge about personality.

Interest in the psychology of everyday life has been most apparent in studies of the personality in context—the context of life events, situations, relationships. The diverse contexts of everyday life reflect specific aspects of the reality in which a person lives: family, work, social environment, culture, relationships. The studies presented on this range of problems, as well as studies of behavior or daily experience, indicate an attempt to shift from describing ideal models of personality to understanding personality through its everyday existence, through the world of human life.

At the same time, data-gathering technologies are changing. The appearance of mobile digital devices and their technical potential for capturing an individual’s everyday activities make it possible to measure individual differences at unprecedented levels of detail and scale. Smartphones are a new source of environment-based behavioral data about a person, significantly expanding the range of data obtained, contributing to a much deeper immersion in the person’s life space.

Although the methodology for constructing such studies has not yet been fully developed and has limitations, network approaches to obtaining personal data and searching for stable personality constructs are already being presented.

Thus, there is a paradoxical situation in modern personality psychology. On the one hand, contemporary reality orients toward the study of personality in line with the challenges a person faces in everyday life. The phenomenology of the personality’s phenomena of being is expanding; the contextual streams are multiplying along which the life of the contemporary individual flows; everyday life and experience are changing. On the other hand, there is still reliance on theories and methodologies developed in the 20th century, when many of the personality phenomena that are today the focus of researchers’ attention for all practical purposes did not exist.

Increased Empirical Data Reflecting the Changeability of Personality Characteristics

One of the grounds for criticism of traditional ideas about the stability of personal characteristics is empirical data about how these change during the lifespan. In modern psychology, extensive material has accumulated about the dynamics of change, even of the most stable and basic personality traits.

For example, the variability of the “Big Five” attributes in youth and middle age mainly pertains to increased agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and social dominance (Lucas & Donnellan, 2011; Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). At older ages, research shows the opposite picture, with a gradual long-term decline in agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness (Berg & Johansson, 2014; Kandler, Kornadt, Hagemeyer, & Neyer, 2015; Lucas & Donnellan, 2011).

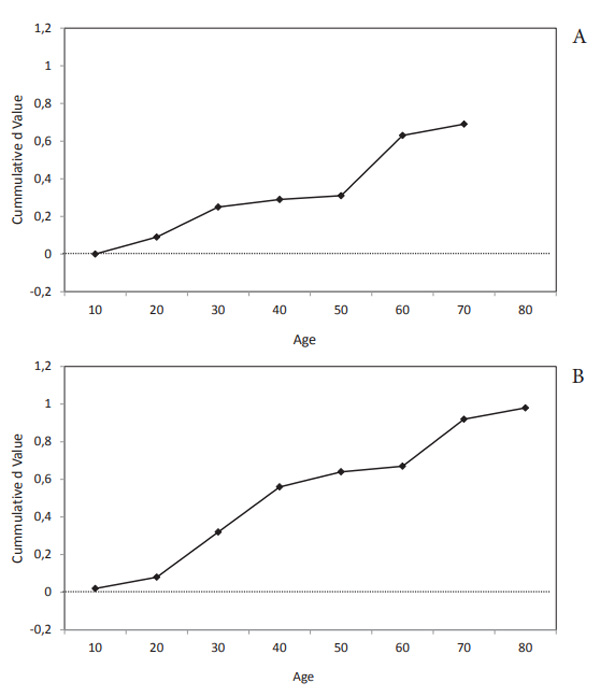

Roberts, Walton, and Viechtbauer (2006) presented the dynamics of personality change across the lifespan by collecting what was at that time one of the largest meta-analytical databases of longitudinal personality traits in adults: 113 samples with a total of 50,120 participants (ages 10 to 100). Meta-analysis of the trajectory of normative changes in trans-situational personality characteristics demonstrates that four of the six measured characteristics change significantly in middle age and late adulthood.

Thus, the dynamic of change in social vitality (the first aspect of the “extraversion” attribute of the Big Five, NEO, California Psychological Inventory) declines with age. However, this change is complex. Standardized mean-level changes show a small but statistically significant increase (d = .06, p < .05) up to age 20, and then two stages of significant reduction: at the age of 22 to 30 (d = -.14, p < .05), and also at age 60 to 70 (d = -.14, p < .05). The second component of extraversion, social dominance, shows a statistically significant increase in adolescence (d = .20,p < .05) and the college years (d = .41, p < .05), as well as two decades of young adulthood (d = .28 and .18, respectively, ps < .05).

Despite the progressive rise in agreeableness across the lifespan (Fig. 3A), the main effect size is from age 50 to 60 (d = .30, p < .05). For the factor “conscientiousness” (Fig. 3B), the dynamic of change affects not only ages 20 to 30, but it also increases significantly at ages 60 to 70 (d = .22,p < .05).

Figure 3. Cumulative scores Agreeableness (A) and Conscientiousness (B) across the life course. (Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006, p. 15)

The pattern of changes for emotional stability is close to that for conscientiousness. However, it can be clearly seen that the dynamic of change also continues from age 50 to 60 (d = .06,p < .05). Openness to experience develops actively in adolescence and the college years (d = .37, p < .05); then the values for this attribute stabilize, and statistically significant values decline in old age (d = .19, p < .05).

Thus, numerous studies demonstrate that personality does change during adulthood. Moreover, continuous changes, decreasing or increasing the intensity of various personality traits, over time also include trans-situational traits.

Increased Attention to Contextual Factors That Influence Personality Change

With the development of behavioral genetics, attempts were made to explain personality changes by genetic factors. Recent literature notes that the relationship of psychological attributes to genetic dispersion is unable to explain as much as 80% of the individual variability of personality characteristics across the lifespan. Environmental influences contribute much more to personality changes.

The dynamic of normative changes in self-esteem (Wagner et al., 2014) is characterized by a gradual increase from adolescence to middle age, reaching a peak at about age 50–60, and then decreasing. However, longitudinal studies show that the rise in self-esteem varies considerably according to the specific trajectories of life. For example, people with high socioeconomic status show greater self-esteem than those with low socioeconomic status, at each stage of life (Wagner et al., 2014).

The context and situation have a substantial impact on personality change.

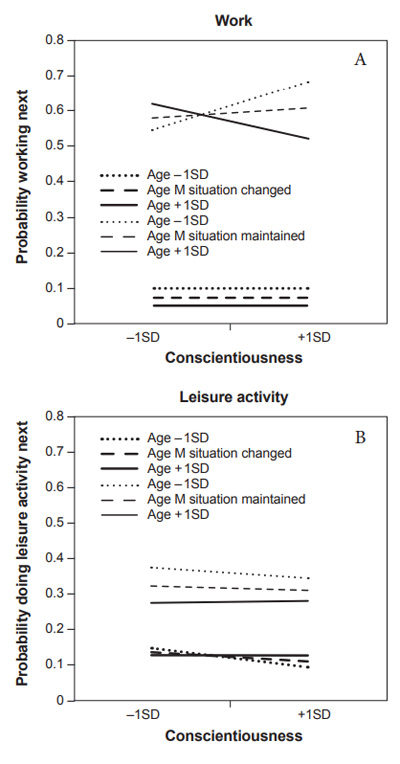

Figure 4 shows changes in conscientiousness in relation to the context of a person’s life.

Figure 4. Trait-age interactions regarding the proximateoccurrence of different situations at the next assessment depending on whether participants were in the same (= situation maintained) or different situation (= situation changed) before: (A) Conscientiousness and age predict doing work activities, (B) Conscientiousness and age predict engaging in leisure activities (Wrzus et al. 2016).

The variability of change and its dependence on context become especially evident when the data is analyzed with reference to stability of the context in a person’s life, whether the situation is stable or changes over a long period.

Figure 4 shows the size of the effects, depending on the variability of the work situation and leisure activities. If there are differences in work conditions (Fig. 4A, lower graph), their change demonstrates that differences still exist (cumulative deffect) in the level of conscientiousness within the age range, equal to one standard deviation. At the same time, if the situation at work is stable or conditions remain similar (Fig. 4A, upper graph), the difference in conscientiousness increases (cumulative effect increases in the range of +1SD).

Active participation in leisure activities is also related to the level of conscientiousness, but in a different way. “Situation changed” (Fig. 4 B, lower graph) scarcely impacts the cumulative effect of differences in conscientiousness depending on the degree of involvement in leisure activity. Meanwhile, situations that are similar for a long time contribute to reducing the differences in the manifestation of conscientiousness between people (in the range of +1SD (Fig. 4 B, upper graph).

These examples clearly demonstrate how personality traits change depending on the context.

To this can be added a great deal more empirical data describing the dynamic, changing nature of personality, including the short-term and diverse effects of intrapersonal variability. For example, personal characteristics change depending on the time a person falls asleep and wakes up, hormonal influences, distinctive features of communication—social, emotional, etc.—and psychological well-being resulting from the quality of social interactions.

Discussion

A dynamic approach to the understanding of personality has become an alternative to the structural-functional system of global, decontextualized, dispositional characteristics (Ashton & Lee, 2007). The changeability of individual characteristics demonstrates the need for dynamic, processual approaches to a personality that is constantly changing yet maintaining its identity (Rubinstein, 2003). Thus, individual models of changeability are key markers in describing the structure of personality. They become the basis for a “descriptive taxonomy” (John & Srivastava, 1999, p. 103), in which the object being described is intra- and interpersonal changeability.

Recognition of the dynamic nature of personality entails a number of methodological issues. The first of these involves development of a conceptual instrument that describes personality change. The second is the definition of an approach that can “capture” the dynamics of personality changes. The third is the development of psychological tools for assessing the personality changes themselves, their dynamics and systematization (conceptualization)

Concerning the first point, it is important to note that in the scientific literature the terms “change”, “development”, and “changeability” are quite often used synonymously. This is partly due to the lack of a precise distinction between psychological definitions of the concepts “development” and “change” as presented in philosophical and psychological literature. Any development obviously must involve change (structural or functional). Development is a special form of change, but these concepts are not completely identical: The concept of “change” has a wider scope than that of “development”, and not every change signifies development. An essential characteristic of change is that it is an alternative to stability. Development sets a vector of change. The concept of change does not reflect the direction of the changes. It characterizes the real phenomenology and processes in which the individual is involved, their mobility and fluidity.

Similarly, the concepts of change and changeability are different. The concept of changeability presupposes instability, variability of some characteristics or functions, fluctuations in the system. In psychological research, the study of changeability of the personality is virtually reduced to analysis of the variability of attributes at the level of situational changes or group comparisons (age, gender, occupation). In this sense, both development and changeability emphasize the dynamism of the personality, but do not reflect its processual nature.

L. Hjelle and D. Ziegler, in their analytical review, introduced the parameter of “changeability–unchangeability” into their system of basic principles underlying theoretical approaches to understanding personality. The authors’ various positions reflect their answer to the question, to what extent is an individual able to change fundamentally during the lifespan (Hjelle & Ziegler, 1976). The processual nature of change is emphasized not by variability or fluctuation, but by the transition to something fundamentally different (a change in structure, state, or function). Personality changes involve not only developmental processes, but also origins, formation, growth, conversion/transformation, etc. They are by nature continuous, which permits us to surmise that it is the processual approach that should become the basis for describing personality as a dynamic structure.

The processual approach (Kostromina & Grishina, 2018) is based on the principle of changeability of the personality, but does not reduce it exclusively to variability. It emphasizes the incompleteness of the action, the openness of the system, its “fluidity”, the fundamental possibility of transforming the personality through the lifespan. The main subject of study in the processual approach is the phenomenology of change.

The question of instruments for psychological evaluation of the processes of personality change remains open. Research on personality changes is commonly based on the longitudinal principle of measuring personality characteristics, which permits description of their dynamics over time. However, this research design, as a rule, does not address the distinctive features of individual experience, life events, which are the most likely factors in personality changes. Even more obvious problems arise in connection with the influence of context, the role of which is emphasized in many studies. Perhaps the potential of digital devices for capturing personality changes in the short-term and medium-term spans of daily activity may be considered as a priority means of studying personality dynamics in real life, compared to traditional methods.

Conclusion

The recognition that personality is in the process of constant change is characteristic of contemporary psychology. Yet the structural-functional model of describing personality, despite recognition of its limitations, retains its dominant influence, especially in empirical research.

At the core of the processes of personality change is the continuous interaction of the individual with the world. Personality is sensitive to the challenges of the individual’s life context, so personality research that does not take this context into account may turn out to be irrelevant. In examples given to demonstrate the influence of different contexts on an individual’s personality traits, in fact it is individual fragments of the overall life context that are presented, without considering their significance with regard to other types of activity.

The need to study environmental and contextual influences is all the more evident in today’s changing reality, the challenges of which also become sources of personal change. Traditionally, changes through a person’s lifespan have been studied mainly as a result of age factors or intrapersonal dynamics. The situation of human existence in the world today forces a return to Kurt Lewin’s concept of life space, which described people’s existence in a field of action of forces that stimulate and restrict their activity, creating tension and points of bifurcation. It is these “zones of tension” that are the sources of change in the phenomenologies of personality, leading to changes in the personality, its life space and life path.

Of particular importance for analyzing personality change is the study of “self-processes” of the personality, related to the potential for self-development and self-change, the study of activity that goes beyond the bounds of adaptive activity as traditionally understood.

Thus, dynamic and integral psychological concepts in describing the interaction of a person with the world, concepts that address the person’s integrality, become highly significant. The search for units of such a description, units that correspond to the principles of a dynamic approach to the study of personality, is the most important methodological task.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of the Government of the Russian Federation, Project No. 18-013-20080.

References

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). The HEXACO model of personality structure and the importance of the H factor. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2,1952–1962. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00134.x

Berg, A. I., & Johansson, B. (2014). Personality change in the oldest-old: Is it a matter of compromised health and functioning? Journal of Personality, 82, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12030

Dickerson, K. & Berlin, J. A. (1992). Meta-analysis: State of the science. Epidemiol Rev, 14, 154–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036084

European Association of Personality Psychology (2014). 17th European Conference on Personality. Lausanne, Switzerland. Retrieved from https://eapp.org/meetings/conferences/conference-2014/

European Association of Personality Psychology (2016). 18th European Conference on Personality. Romania. Retrieved from http://www.eapp. org/meetings/conferences/ecp18/

European Association of Personality Psychology (2018). 19th European Conference on Personality. Zadar, Croatia. Retrieved from https://eapp.org/meetings/conferences/conference-2018/

Giordano, P. J. (2015). Being or becoming: Toward an open-system, process-centric model of personality. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 49(4), 757–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-015-9329-z

Giordano, P. J. (2017). Individual personality is best understood as process, not structure: A Confucian-inspired perspective. Culture and Psychology, 23(4), 502–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X17692118

Gosling, S. (2016). No excuses, it’s time to study real people in the real world. Abstract book of the 18th European Conference on Personality, 19–23 July 2016, Romania (p. 115). Retrieved from http://www.eapp. org/meetings/conferences/ecp18/

Grishina, N. V., Kostromina, S. N., & Mironenko, I. A. (2018). Struktura problemnogo polia sovremennoi psikhologii lichnosti [The structure of the problem field in modern personality psychology]. Psikhologicheskii zhurnal, 39(1), 26–35.

Heatherton, T. & Weinberger, J. (Eds.) (1994). Can personality change? Washington: APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/10143-000

Hjelle L., Ziegler D. (1976). Personality theories. Basic assumptions, research, and applications. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Inkeles, A., & Smith, D. (1974). Becoming modern. Individual change in six developing countries. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674499348

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big-five factor taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press.

Kandler, C., Kornadt, A. E., Hagemeyer, B., & Neyer, F. J. (2015). Patterns and sources of personality development in old age. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014996

Kostromina, S.N., & Grishina, N.V. (2018). The future of personality theory: A processual approach. Integr. psych. behav.52(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-018-9420-3.

Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. (2011). Personality development across the life span: Longitudinal analyses with a national sample from Germany. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 847–861. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014996

Roberts, B. W., & Mroczek, D. (2008). Personality trait change in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 31– 35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00543.x

Roberts, B.W., Walton, K.E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1

Rubinstein, S.L. (2003). Bytie i soznanie. Chelovek i mir[Being and consciousness. Man and world]. St. Petersburg: Piter.

Special issue: Status of the trait concept in contemporary personality: Are the old questions still the burning questions? (2018). Journal of Personality, 86(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12335

Wagner, J., Lang, F. R., Neyer, F. J., & Wagner, G. G. (2014). Self-esteem across adulthood: The role of resources. European Journal of Ageing, 11, 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-013-0299-z

Wagner, J., Ram, N., Smith, J., & Gerstorf, D. (2016). Personality trait development at the end of life: Antecedents and correlates of mean-level trajectories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(3), 411-429. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000071

Wrzus, C., Wagner, G. G., & Riediger, M. (2016). Personality-situation transactions from adolescence to old age. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110, 782–799. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000054

To cite this article: Kostromina, S.N., Grishina, N.V. (2019). The Dynamic Personality: ‘Continuity Amid Change’. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 12(2), 34–45.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.