Polar Meaning-Building Strategies: Acmeological Characteristics

Abstract

Background. Personality is not simply an end product, but rather, it is a process. Therefore, empirical work on personal meaning-building should examine the genesis of meaning and provide a content-based description of personality in terms of personality traits. Such a description suggests a systemic view of personality, where the meaning-based approach is supplemented with the definition of personality traits. The value and meaning potential of personality encompasses three dimensions: worldview, behavior, and cognition.

Objective. The aim of this study is to identify the properties of personality, reflecting the features of polar strategies of meaning formation in acmeological terms by age, gender, and professional characteristics.

Design. The present study considers the influence of various acmeological factors on meaning-building and concentrates on its two polar strategies: adaptive and developing strategies. We developed nine bipolar scales of personal traits with sublevels by applying the semantic differential technique. In total, there were 145 participants in the study. Participants were grouped according to three criteria: age, gender, and profession.

Results. The obtained indices of meaning-building strategies did not coincide in all the differentiated groups, which clearly speaks in favor of acmeological dynamics of the respondents’ personal profiles. We stratified the sample according to the mean score of the basic marker of “life meaningfulness,” which enabled us to establish differences in characteristics of actual polar strategies of meaning-building. e respondents who did not fall into either of the two groups are “between the poles.” They often have an under- developed meaning-building strategy as a result of poorly formed ways of organization and actualization of personal meanings or the presence of a transitional form of situational conceptual initiations.

Conclusion. The personal profiles that were identified represent multifactor models of the personal value and meaning dimensions, which can predict actual meaning-building strategies using semantic differential scales and indicators (“life meaningfulness” from the Purpose-in-Life test) and help researchers to reduce the number of techniques employed in their studies.

Received: 22.02.2018

Accepted: 28.11.2018

Themes: Personality psychology

PDF: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2018_4/psych_4_2018_13_Abakumova.pdf

Pages: 200-210

DOI: 10.11621/pir.2018.0413

Keywords: personality, meaning, meaning-building strategy, development, adaptation, polarity, semantic scale

Introduction

The aim of this study is to identify the properties of personality, reflecting the features of polar strategies of meaning formation in acmeological terms by age, gender, and professional characteristics. Personality development takes place in a constantly changing society. Continuous changes and life crises create various transformations in personal value and meaning sphere. The genesis of personal meanings depends on both external conditions and internal subjectivity. Various acmeological factors, showing the possibility of achieving the highest level of individual development, influence the individual meaning. They change the trajectories of meaning-building, the actualization of meaning in certain life circumstances, and transmission during various interactions (Abakumova, Ermakov, & Fomenko, 2013). Modern theories of meaning define meaning-building strategies as dynamic characteristics of personal value-motivational activity (D. Leontiev, 2007). It is the strategy of meaning-building that manifests in the system of meaning in consciousness, which entails the actualization of primary meanings and their dominance in specific interaction situations. Meaning-building strategies orient personal development trajectories in various periods of life and determine the stability of self-development and characteristics of self-identification.

Specific characteristics of primary meaning-building strategies depend on the presence and unity of three components: (a) an initiating principle, (b) the content, and (c) the direction of the development of meanings. The meaning-building strategy is a way of forming and developing the system of personal meanings, which is organized in terms of motives, needs, goals, experience, and subjective relations; it also reflects the specific characteristics and dynamics of individuals’ actualization of meanings in specific life situations (Abakumova, Godunov, Enin, & Generdukaeva, 2016). Such a definition of meaning-building strategies can assist in our understanding of both possible and actual ways of organizing personal meaning dimensions, which contain various qualitative preferences and views. This offers new opportunities for studying features of meaning regulation during individuals’ interactions in specific decision-making situations. The processes of estimation and choice reflect adherence to various meaning-building strategies. The present paper presents an empirical study of the acmeological characteristics of these strategies.

The issues of alternative estimation, contrast, and choice are relevant for the ontological framework of personal development. Besides, these issues represent a teleological tool for all branches of the humanities. This is where psychology considers and supplements its specific approach, which reflects the multidimensionality of meaning as a category. At the same time, the issues of polar estimation and contrast are associated with different levels of such phenomena. As applied to value-meaning categories, individuals often express polar points of view. However, many psychological constructs have a dichotomous continuum structure at the empirical level and in everyday life. In its most elementary form, this structure reflects the presence of two alternative poles (attractors) as sources for the development of the system. The simplest logical choice is the choice between two states as opposites on a dipole.

In his three-level model of personality, D. Leontiev (1997) demonstrated that personality structure contains personal meanings (core layer) and personal traits (surface layer), which receive their nourishment from the core layer and reflect its essence. This correlation between structural levels of personality may be considered as a correspondence between personal traits and meanings. In this case, there is a mutual correspondence between the system of personal meanings and personal traits in several of their associations. On one hand, this means that personal traits reflect only the meanings that exist in the value-meaning sphere and the world outlook core of personality. On the other hand, personal meanings influence the characteristics of individuals’ interactions, as well as judgments and relationships in various situations, which manifests in certain personal traits as distinctive characteristics. Thus, personal meanings are prototypes, and personal traits are isomorphic images as derivatives of meanings. Consequently, the correspondence between personal meanings and personal traits reflects their integrity and identity, which can only be observed in mentally healthy individuals.

In other words, meanings represent personal internal structure. Their properties are external (surface contact layer) and manifest themselves in interactions. The mechanism of correspondence between personal meanings and personality traits consists in personal interactions and individuals’ lives in their various manifestations. Meanings are instrumental in manifesting and actualizing personality traits in interactions. The presence of certain personality traits speaks in favor of actual meanings. Allport (2002) notes that personality traits are the driving elements of human behavior. For example, curiosity serves as a mechanism for achieving well-being and finding the meaning of life (Kashdan & Steger, 2007).

In his study of personality development, Lazursky (1924) concluded that it is impossible to create a unified personality typology. He suggested the classification of personal levels of maturity, which reflect individuals’ development and activity in society. Lazursky’s classification embodied the following components: (a) passive adaptation to reality, (b) active adaptation to reality, (c) individuals’ adaptation of reality to themselves, and (d) realization of human ideals and creativity of “knights of spirit.”

The foregoing theories illuminate two meaning-building strategies aimed at adaptation and development of meanings. We define these strategies based on their components (Abakumova et al., 2016) as follows:

-

Adaptive strategy of meaning-building refers to organizing the dimensions of meanings in a way compensates for defects in individual development through adjustment and monotonous movement in the layer of acquired personal meanings under the influence of the external environment dominating and determining individuals’ vital activity. This strategy is based on formal and stereotyped goals.

-

Developing strategy of meaning-building refers to transforming the dimensions of meaning in a way that tends to build prospective meanings and transforms their content under the influence of external factors, which individuals assess as living conditions that can be overcome. This strategy is focused on understanding the motives and generating actual goals, which are important for personal growth.

According to J. Piaget’s operational concept of intellect, the process of adaptation of mental activity includes assimilation and accommodation mechanisms (Piaget, 1998). Thus, the suggested strategies for regulating the dimensions of personal meanings reflect the characteristics of cognitive development.

In one of his final interviews, Abraham Maslow stated that the satisfaction of basic needs does not always provide inevitable and unconditional self-actualization. He argued that when individuals achieve the level where their basic needs are met, some continue to move towards self-actualization, while others stop moving (Frick, 2000). The presence of such a phase meaning “crossing the Rubicon” suggests that dimensions of meaning may be organized in accordance with strategies reflecting the actualized personal preferences for either adaptation or development.

D. Leontiev examined the characteristics of life strategies in the form of two primary alternatives, where symbiotic survival as an escape from responsibility towards collective personality can be contrasted with a transcendent autonomy for true personal growth, when a person “needs the most” (D. Leontiev, 2002). Because of the above-stated dichotomies of meaning, individuals give priority to certain things in comprehension. In other words, they make a choice as a divergence in the process of meaning-building. The concepts of divergence and convergence reflect a variative branching into independent tendencies, converging from different sides to develop in a single direction. To study creative abilities and creativity, Guilford (1967) suggested the concept of divergent and convergent thinking, noting a fundamental difference between two types of mental operations: convergence and divergence. Convergent thinking is associated with finding correct solutions to various problems. Divergent thinking is multidirectional. This type of thinking helps individuals vary problem-solving methods and leads to unexpected conclusions and results (Druzhinin, 2009).

Such a dichotomy in the development of meaning dimensions allows us to conclude that the bipolarity of meanings manifests in their transfer to the external layer, where they meet other meaning systems. According to A. Leontiev, such a “decrystallization” transforms meanings into personal ones. However, meanings become personal based on their consonant or dissonant positioning. Such an interpretation of acceptance/rejection (coincidence/noncoincidence) in actual meaning dimensions provides a dyadic space along with bipolar meanings (meaning continuum).

When ordering complex descriptive personality traits, their linear arrangement may be useful. In its simplest form, such a sequential arrangement has one or two poles (attractors) as sources of the development of various systems including “the physical world, although its description contains bipolar characteristics (distant/close) and unipolar characteristics from zero to infinity. Closeness is the least degree of remoteness. However, we use bipolar characteristics when describing others” (Petrenko, 2013, p. 181).

Interpretations of others contain at least two points of view, which reflect their similarities and differences. This corresponds to Kelly’s (1955) constructive alternative approach. Such a process of contrasting creates meaning constructs, which correspond to alternative ways of perceiving the world and lifestyles. In general, meaning constructs are bipolar characteristics that contain opposing relationships as alternatives. Within the framework of personal constructs, Kelly (1955) concluded that when individuals indicate something concrete, they also mean an opposite state or property. In contrast to the “similarity/difference” of Kelly’s personal cognitive constructs, the meaning dissonance perspective suggests that the features of meaning-building strategies should be considered using the “acceptance/rejection” bipolar meaning constructs.

Personality is not simply an end product, but rather, it is a process. Therefore, an empirical study of personal meaning-building should examine the genesis of meanings and provide a content description of personality in terms of personality traits. For example, Cattell (1965) supposed that each word denoting a certain personality trait is its potential representation. Revealing a complex ensemble of personality traits, as content that colors subjectivity, has certain difficulties, as “the meaning approach is absolutely adequate. Unlike personality traits or dispositions, variability and dynamism are inherent in the very nature of meaning structures and systems. When researchers describe personality in terms of personality traits, they have difficulties over explaining the mechanisms of personal changes. It is obvious that the language of traits is clearly inadequate for these purposes” (D. Leontiev, 2007, p. 253).

Bipolar scales with intermediate sublevels should help to overcome such difficulties. These bidirectional semantic axes represent two related personality traits as well as directions referring to both positive and negative development. These semantic axes reflect the directions of symmetry in the many-sided meaning space of personality and demonstrate the dynamics of changes. Thus, the above-stated difficulties can be overcome by virtue of a “theory that creates the possibility of changes in its explanatory structures” (D. Leontiev, 2007, p. 253).

It may be appropriate to define personality from the perspective of the interdisciplinary approach to meaning dimensions. Many mental processes, states, and properties differ in their nature. However, together, they constitute the sphere of the human psychic. Their differentiation and separate analyses may be superfluous. It is unnecessary to discuss the need to distinguish the concepts of personality traits and characteristics when they are similar and sometimes coincident (A. Leontiev, 1975). Hence, the concept of “personality trait” is broader than is the concept of “character trait,” and broader yet than the concept of “psychic trait.”

Individuals’ perfection is determined by their harmonious interactions in both internal and external spaces of their personality. These spheres are not isolated ones; they often overlap and supplement each other. The scope of interactions and their intensity manifest themselves in personal individuality: “As a rule, the man’s properties can be called personal if they characterize him as a subject of relations with the surrounding world and are formed in the relationship with the world” (Lubovsky, 2007, p. 187).

The complex of personality traits is a unique combination that provides an inimitable “pattern” in the diversity of the world of people, things, and relationships. Therefore, personal harmony assumes the paths of development that help individuals approach and correspond to certain key concepts, which reflect their understanding of happiness and meaning of life.

Method

Instrument

The scales of personality traits establish the features of their manifestation in various dimensions of personal functioning. According to Rokeach (1973), the value and meaning dimensions of personality regulate the choice of goals and means of activity in accordance with generalized representations of possible benefits and ways to achieve them. Moreover, personal meanings (as life values) activate appropriate strategies for personal development. The value and meaning potential of personality encompass three main dimensions (Diakov, 2015; Kotlyakov, 2013; Pakhomova, 2011): world outlook, behavior, and cognition.

Each of these dimensions should be described using the language of personality traits by means of bipolar meaning scales. In these scales, personality traits are key denotations as specific markers of meanings. The findings of our studies enabled us to select nine personality scales (Godunov, 2016), which correspond to the developmental and adaptive strategies of meaning-building. For each scale, the three upper words refer to the developmental strategy of meaning-building (+), the middle level shows a neutral state (0), and three lower words refer to the adaptive strategy (-) (Table 1).

Table 1

Personal Property Scales

|

1) world outlook direction: +3 self-sufficiency +2 meaningfulness +1 responsibility 0 disinterest -1 levity -2 inadvertence -3 disorganization |

2) behavioral direction: +3 tranquility +2 civility +1 leniency 0 indifference -1 bravado -2 impatience -3 inadequacy |

3) verbal-linguistic: +3 eloquence +2 erudition +1 originality 0 conventionality -1 narrowness -2 categoricity -3 stereotype |

|

4) logical-mathematical direction: +3 abstractiveness +2 systemacy +1 logicality 0 linearity -1 inconsistency -2 fragmentariness -3 banality |

5) visual-spatial direction: +3 imagery +2 expressiveness +1 accuracy 0 mediocrity -1 disorder -2 disunity -3 disproportion |

6) motor-leading direction: +3 vitality +2 plasticity +1 mobility 0 ordinariness -1 mismatch; -2 sluggishness -3 passivity |

|

7) musical and rhythmic direction: +3 rhythmicity +2 musicality +1 proportion 0 mediocrity -1 narrowness -2 obsession -3 monotony |

8) interpersonal direction: +3 sociability +2 trustfulness +1 benevolence 0 lack of interest -1 hesitation -2 distrustfulness -3 isolation |

9) intrapersonal direction: +3 confidence +2 calmness +1 attentiveness 0 unpretentiousness -1 emotionality -2 irritability -3 suspiciousness |

The developed scales of personality traits represent personal profiles and demonstrate actual strategies of meaning-building.

The system of personal meanings and the strategies for building them represent a multifaceted and multidirectional conceptual sphere. However, no research has addressed the issue of a unified methodology or approach. We supplemented the developed scales of personality traits with a battery of psychodiagnostic tests. Our study used the following techniques: (a) the Who Am I test by Kun and McPartland (modified by Rumyantseva, 2006) to investigate the content characteristics of personal identity; (b) the Purpose-in-Life test (PIL) modified by D. Leontiev to examine the factors of life meaningfulness (D. Leontiev, 2000); (c) the Rosenzweig Picture-Frustration Test to analyze behavioral characteristics (Rosenzweig, 1945); and (d) Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences test to describe the characteristics of cognition (Gardner, 1983).

Participants

Our empirical study of the psychological characteristics of polar estimation regarding different strategies of meaning-building involved first- and third-year psychology and history students studying at Southern Federal University as well as secondary school teachers residing in the Rostov region (n = 145). The participants were grouped according to three criteria: age, gender, and profession. The sample consisted of 102 young people aged 18–23 years and 43 people aged 26–56 years; 112 women and 33 men; and 80 psychology students, 30 history students, and 35 secondary school teachers.

Procedure

After grouping the participants according to their acmeological characteristics, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients for test scores. The stable presence of positive correlations (ps ≤ .05) with the proposed meaning scales were found only for the “life meaningfulness” index in the PIL test. Consequently, we considered this parameter as the main marker of polar strategies of meaning-building. The “life meaningfulness” measure in D. Leontiev’s PIL test refers to conscious self-reflection. There were no statistically significant correlations between the meaning scales and other measures. Differences of mean scores in groups based on acmeological characteristics were determined using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion. For the index “life meaningfulness” as a function of age, sex, and profession, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion did not exceed .044, suggesting significant differences in the sample groups (ps ≤ .05).

We further divided the samples into two groups based on the mean scores of “life meaningfulness.” Respondents with higher scores fell into the group with a developing strategy of meaning-building. Those with lower scores fell into the group with an adaptive strategy of meaning-building. In each group, we evaluated mean scores for semantic differential scales. These indices reflect the parameters of personal psychological profiles for the polar strategies of meaning-building.

Results and Discussion

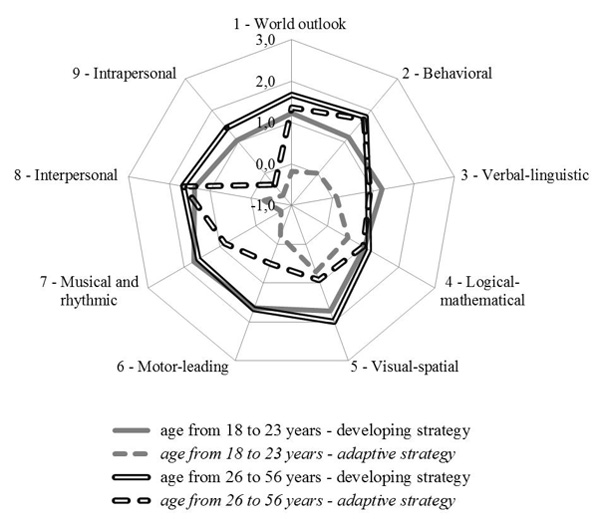

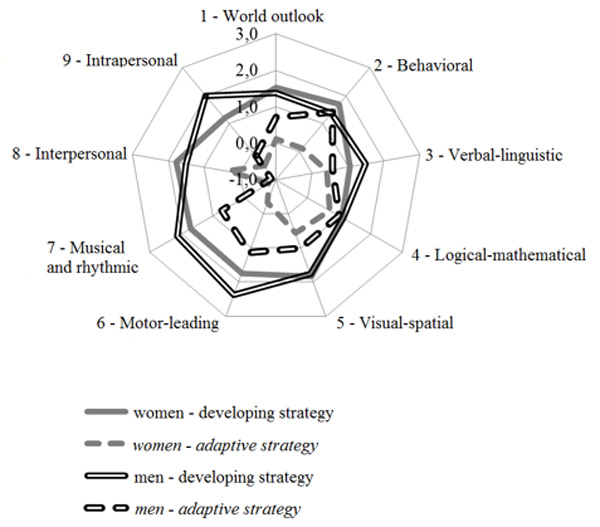

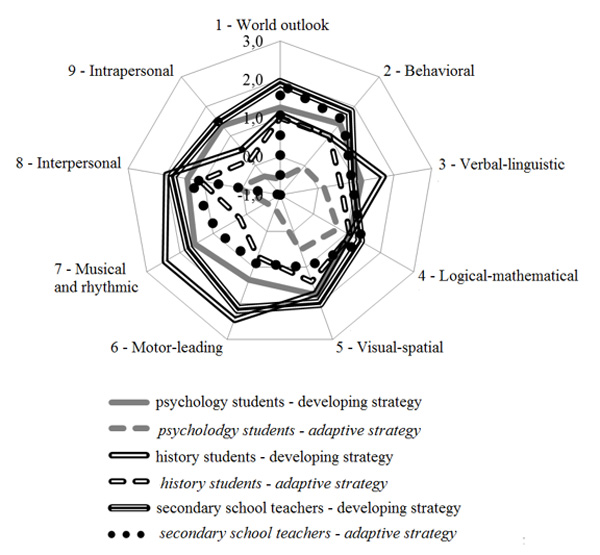

Figures 1–3 show nine semantic differential scales of personal traits that underlie the construction of personal profiles in terms of polar meaning-building strategies. Such an approach enables us to reveal the dynamics of the investigated meaning-building strategies and changes in their indices in terms of acmeological characteristics.

Figure 1. Age changes in meaning-building strategies on semantic differential scales.

When we grouped the respondents with respect to their age (see Figure 1), both age from 18 to 23 years and age from 26 to 56 years groups showed higher scores on the developing strategy. Furthermore, compared with the young respondents, the middle-aged participants had higher or equal scores on most semantic differential scales, with the exception of scale 3 (“verbal-linguistic”). The middle-aged respondents had higher scores on the adaptive strategy of meaning-building on all scales.

Figure 2. Gender changes in meaning-building strategies on semantic differential scales.

When we grouped the respondents with respect to their gender (see Figure 2), both genders showed higher scores on the developing strategy, with the exception of coincidence on scales 2 and 4 in the male group. Compared with male respondents, women showed higher scores on the developing strategy on scales 1, 2 and 8; equal scores on scales 4 and 5; and lower scores on scales 3, 6, 7, and 9. Male respondents had higher scores on the adaptive strategy on all the scales, with the exception of scale 8 (“interpersonal”).

Figure 3. Differences by profession in meaning-building strategies on semantic differential scales.

When we grouped the respondents with respect to their profession (see Figure 3), all the professional groups had higher scores on the developing strategy, with the exception of coincidence on scales 2 and 4 among secondary school teachers. The secondary school teachers demonstrated the highest scores on the developing strategy on scales 1, 2, 4, 5, and 9, while the history students had the highest scores of the developing strategy on scales 3, 6, 7, and 8. The secondary school teachers demonstrated the highest scores of the adaptive strategy, with the exception of scales 5 and 9 in the history students group.

Conclusion

The obtained indices of meaning-building strategies did not coincide in all the differentiated groups, which clearly speaks in favor of acmeological dynamics of the respondents’ personal profiles. We stratified the sample according to the mean score of the basic marker of “life meaningfulness,” which enabled us to establish differences in characteristics of actual polar strategies of meaning-building. The respondents who did not fall into either of the two groups are “between the poles.” They often have an underdeveloped meaning-building strategy as a result of poorly formed ways of organization and actualization of personal meanings or the presence of a transitional form of situational conceptual initiations.

The identified personal profiles represent multifactor models of personal values and meaning dimensions, which can predict actual meaning-building strategies using semantic differential scales and indicating markers (“life meaningfulness” from the Purpose-in-Life test) and help researchers to reduce the number of techniques employed in their studies. Further research should pursue a trialectical analysis of meaning-building strategies.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out as a part of the Southern Federal University internal grant implementation No. 07/2017-01 “Development of technologies for the initiation of meaning-making as a component of modern communication systems for the purpose of ensuring the information security in the Internet.”

References

Abakumova, I.V., Ermakov, P.N., & Fomenko, V.T. (2013). Newdidactics: Book I: Methodology and technology of training: Searching a developing resource. Moscow: Credo.

Abakumova, I.V., Godunov, M.V., Enin, A.L, & Generdukaeva, Z.Sh. (2016). Meaning-building strategies: Modern representations in the works of native researchers: textbook. Moscow: Credo.

Allport, G.W. (2002). Formation of personality. Selected works. Moscow: Smysl.

Cattell, R.B. (1965). The Scientific Analysis of Personality. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books.

Druzhinin, V.N. (2009). Psychology: A textbook for humanitarian institutions (2nd ed). St. Petersburg: Piter.

Dyakov, S.I. (2015). Sub’ektnaia samoorganizatsia lichnosti. Psikhosemanticheskii analiz [Subjective self-organization of personality: psychosemantic analysis]. Vestnik Omskogo universiteta. Seriia: Psikhologia [Herald Of Omsk University. Series: Psychology], 1, 15-33.

Frick, W. (2000). Remembering Maslow: Reflections on a 1968 interview. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 40(2), 128-147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167800402003

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. N.Y.: Basic Books.

Godunov, M.V. (2016). The ensemble of personality traits: Interpreting and diagnosing bipolar semantic scales. Book 1. Moscow: Credo.

Guilford, J.P. (1967). The nature of human intelligence. N.Y.: McGraw-Hill Book & Co.

Kashdan, T.B., Steger, M.F. (2007). Curiosity and path-ways to well-being and meaning in life: Traits, states, and everyday behaviors. Motivation and Emotion, 31(3), 159-173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-007-9068-7

Kelly, G. (1955). The psychology of personal constructs. N.Y.: Norton.

Kotlyakov, V.Yu. (2013). Metodika "Sistema zhiznennykh smyslov" [The System of Vital Meanings technique]. Vestnik Kemerovskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta [Bulletin of Kemerovo State University], 2 (54), 148-153. https://doi.org/10.21603/2078-8975-2013-2-148-153

Lazursky, A.F. (1924). Klassifikatsiia lichnosti [Personality classification]. In M.Ya. Basov & M.N. Myasishchev (Eds), Lazursky, A.F. (3nd ed). Leningrad: State Publishing House.

Leontiev, A.N. (1975). Deiatelʹnostʹ. Soznanie. Lichnostʹ [Activity. Consciousness. Personality]. Moscow: Politizdat.

Leontiev, D.A. (1997). Ocherk psikhologii lichnosti [Essay on the psychology of personality]. (2nd ed.). Moscow: Smysl.

Leontiev, D.A. (2000). Test zhiznennykh orientatsii [Test life orientations]. (2nd ed.). Moscow: Smysl.

Leontiev, D.A. (2007). Psikhologiia smysla: priroda, struktura i dinamika znacheniia realʹnosti [Psychology of meaning: Nature, structure and dynamics of meaning reality] (3nd ed.). Moscow: Smysl.

Leontiev, D.A. (2002). Simbioz i adaptatsiia ili avtonomiia i transtsendentnostʹ: vybor cheloveka v nepredskazuemom mire [Symbiosis and adaptation or autonomy and transcendence: The person’s choice in an unpredictable world]. In Ye.I. Yatsuta (Eds), Lichnostʹ v sovremennom mire: ot strategii vyzhivaniia k strategii sozdaniia zhizni [Personality in the modern world: from the survival strategy to the strategy of life creation] (pp. 3-34). Kemerovo: IPK Graphica, 2002.

Lubovsky, D.V. (2007). Vvedenie v metodologicheskie osnovy psikhologii [Introduction to the methodological foundations of psychology]. Moscow: Modek, MPSI.

Pakhomova, E.V. (2011). Metodika otsenki tsennostnykh orientatsii [Value orientations assessment technique]. Vestnik Samarskoi gumanitarnoi akademii. Seria “Psikhologia” [Herald of the Samara Humanitarian Academy. Series "Psychology"], 2(10), 120-134.

Petrenko, V.F. (2013). Mnogomernoe soznanie: psikhosemanticheskaia paradigma [Multidimensional consciousness: A psychosemantic paradigm]. 2nd ed. Moscow: Eksmo.

Piaget, J. (1998). O mekhanizmakh assimiliatsii i akkomodatsii [On the mechanisms of assimilation and accommodation]. Psikhologicheskaia nauka i obrazovanie [Psychological science and education], 1, 22-24.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. N.Y.: Free Press.

Rosenzweig, S. (1945). The picture-association method and its application in a study of reaction to frustration. Journal of Personality, 1(14), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1945.tb01036.x

Rumyantseva, T.V. (2006). Psikhologicheskoe konsulʹtirovanie: diagnostika semeinykh otnoshenii [Psychological counselling: diagnostics of couple relationships]. St. Petersburg: Rech.

To cite this article: Abakumova I. V., Ermakov P. N., Godunov M. V. (2018). Polar Meaning-Building Strategies: Acmeological Characteristics. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 11 (4), 200-210.

The journal content is licensed with CC BY-NC “Attribution-NonCommercial” Creative Commons license.